Julius Caesar represents more than just ancient Rome today; he represents the entire world. Scholars agree that he was the impetus behind the rise of modern Europe. Caesar possessed an abundance of charisma, a quality crucial for a politician and a statesman. He won the hearts of many of his contemporaries and successors. His reputation as an exceptional leader and politician, a brilliant orator and writer, and a multitalented genius has stood the test of time. Julius Caesar’s commentaries on the Gallic and civil wars is his main contribution to the literature. Caesar’s writings were studied for their military advice and inspiration. It’s no coincidence that in the Roman catacombs of The Count of Monte Cristo, Alexandre Dumas does not miss the chance to mention Caesar’s Commentaries.

- 1- Caesar was born by Caesarean section – hence the name of the operation

- 2- Caesar fought Asterix and Obelix, but could not defeat them

- 3- Did Caesar crossed the Rubicon and said: “The die is cast (Alea iacta est)”

- 4- Caesar seized power in Rome by force

- 5- Caesar had an affair with Cleopatra

- 6- Caesar is the author of “I came; I saw; I conquered (Veni, vidi, vici)”

- 7- Caesar was a dictator

- 8- Caesar was treacherously murdered by his best friend, and before he died he said: “And you, Brutus? (Et tu, Brute?)”

- 9- Caesar was a good writer

- 10- Caesar wore a laurel wreath to hide his bald head

- 11- Caesar could do three things at the same time

- 12- The word “king” also comes from Caesar

- 13- Caesar came up with the salad of the same name

Caesar’s terrible death as a martyr has been glorified and has provided artists with endless fodder for their craft. Dante put Brutus and Cassius, the two primary Caesarean killers, in the Ninth Circle of Hell, where they are tormented by Lucifer himself for being traitors of human grandeur along with Judas, a traitor to divine glory. Numerous anecdotes, semi-legendary tales, and common adages have Caesar as their inspiration or central figure. Examining the ancient traditions allows readers to establish their own impressions of the Roman dictator, who is certainly not simple to assess objectively.

1- Caesar was born by Caesarean section – hence the name of the operation

Before the time of Julius Caesar, obstetricians routinely performed procedures similar to the Caesarean section (“sectio caesarea”). Dionysus, the god of wine, and Asclepius, the god of healing, were both taken from the wombs of deceased mothers in Greek mythology and resembled genuine medical instances. Ancient Indian, Chinese, Babylonian, Iranian, and other texts also make reference to this procedure. Laws enacted by King Numa Pompilius (“leges regiae”) of ancient Rome prohibited the burial of a pregnant woman without first removing the fetus. This was the case 700 years before Caesar was born.

Pliny the Elder says that several well-known Romans were born by Caesarean section. These include Scipio Africanus, who beat Hannibal, Manius Manilius, who led an army into Carthage, and the first of Caesars (not Julius Caesar himself). Pliny states that Caesar’s ancestor was prematurely delivered through the cutting of the mother’s womb (caeso). Thus, comes the family name of the Caesars: a caeso matris utero dictus.

Born around 100 or 101 BC, Julius Caesar is considered one of the most influential figures in history. Due to the aforesaid rule, fetal removal was only performed when the mother was either near death or had already passed away, as it was not possible to perform the procedure in a way that would have kept both mother and child alive at the time. Additionally, we know that Caesar’s mother Aurelius lived through delivery and passed away in old age in 54 BC because of the accounts of Suetonius.

This is an example of a fabricated etymology. Explaining this misunderstanding is challenging. Pliny’s participle caesus (“dissected,” “cut up”), produced from the verb caedere, may have been mistaken for the adjective caesareus (“from Caesar”) by subsequent authors, in particular the developers of the 10th-century Byzantine Dictionary of the Court. Legend has it that caesareus, or “Caesar,” was named after him. The mythology of Caesar’s birth was already widely circulated by the Middle Ages, with many medieval manuscripts featuring scenes of the young Caesar being ripped from his mother’s womb.

Verdict: Hardly.

2- Caesar fought Asterix and Obelix, but could not defeat them

Claude Zidi’s film “Asterix and Obelix vs. Caesar“, based on the comic books by René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo, is based on characters that do not exist in real life. Long hair and breeches, a barbarous garment severely loathed by the Romans, are the only features they share in common with the actual Gauls of history.

It is true that Caesar was at war with the Gauls, and he was victorious. He held the office of consul in 59 BC. Following his year as consul, Caesar often served as viceroy with proconsular powers in a Roman province for the following year. Caesar foresaw this and had a law passed through a people’s tribune that gave him control of Cisalpine Gaul and Illyric (present-day Albania and Croatia) for five years.

The Senate later added Gallia Narbonensis (“Gaul of Narbonne,” modern-day Provence), which the Romans had conquered in the last third of the second century BC. Transalpine Gaul, or “Gaul on the far side of the Alps” was the target of Caesar’s conquest plans. This region was roughly the size of modern-day France, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Switzerland combined. Due to the Gallic fashion of having long hair, the Romans also referred to this untamed land as Gallia Comata.

Caesar won early victories in the war by subjugating many of the Gallic tribes and defeating the Germanic tribes that had invaded Gaul. Caesar’s mandate was extended for another five years in 56 BC.

All of the native tribes of Gaul, including the Eburones, Belgae, Nervians, and others were ready to erupt at any moment. The all-Gaulish great uprising, which started in the winter of 53 BC, was the biggest difficulty the Romans ever faced. Vercingetorix, a youthful leader of the Arverni people, commanded the army in the year 52. It was true that Caesar had to retake Gaul. By the end of 51 BC, the Romans had finally managed to bring peace to Gaul.

Related: Battle of Alesia: Caesar’s victory over Vercingetorix

Caesar “he took by storm more than eight hundred cities, subdued three hundred nations, and fought pitched battles at different times with three million men, of whom he slew one million in hand to hand fighting and took as many more prisoners,” as Plutarch puts it, during the years Caesar spent in Gaul. Despite the questions that these unbelievable numbers pose, the outcomes of the Gallic Wars were outstanding. Rome captured a sizable territory and made massive plunder. Caesar benefited monetarily, but more crucially, by acquiring an army that was disciplined, experienced, and loyal.

The relatives and offspring of Asterix and Obelix were quickly Romanized. Caesar had already appointed a number of Gauls to the Roman Senate, and they celebrated their newfound status with songs like “Galli bracas deposuerunt, latum clavum sumpserunt,” which translates to “The Gauls set aside their bracae [a trousers of Gauls], and took up the laticlave” The Roman upper magistrates and senators wore the pretense toga, distinguished by its wide purple border. After another few centuries, the Gauls would abandon their Druid priests and their own language in favor of a distorted form of Latin. Gaul eventually became one of the Roman Empire’s most Romanized regions.

Verdict: Wrong.

3- Did Caesar crossed the Rubicon and said: “The die is cast (Alea iacta est)”

This took place at the outset of the dramatic civil war between Caesar and Pompey. Even though they were related (Julia, Caesar’s only daughter, married Pompey), the erstwhile allies of the first triumvirate turned out to be bitter enemies.

Julia passed away during delivery in 54 BC, and Crassus was killed in a failed Parthian war the following year, in 53 BC. For all intents and purposes, this spelled the end of the triumvirate. In Gaul, Caesar was racking up victory after victory. Pompey, on the other hand, was envious of Caesar because he believed the Gallic viceroy would eventually surpass him as Rome’s most capable military leader due to the viceroy’s growing popularity.

Caesar’s opponents in the Senate brought up the idea of removing his authority over Gaul sooner rather than later. At first, Pompey approved of these plots, but eventually he publicly aligned himself with Cato the Younger’s radical Optimates, who were adversaries of Pompey’s ex-father-in-law. Since the Optimates saw both Caesar and Pompey as prospective tyrants out to destroy the Senate, they opted for the lesser of two evils and formed an alliance with Pompey.

As of March 1, 49 BC, Caesar’s mandate was officially due to end. Caesar planned to run for consul (while he was absent), thus he could switch from pro-consul to consul simply by resigning his current position. But his detractors called for his urgent presence, planned to put him on trial: The Gallic Command’s years of operating autonomously and without consideration for the Senate had amassed enough evidence against it. Pompey and the radical Optimates demanded a resolution for Caesar to relinquish his authority and dissolve the army during a Senate sitting on January 1, 49 BC.

In the event that the Gallic commander would not comply, Caesar was labeled an “enemy of the fatherland.” At 49 years old, Caesar heard about the turmoil in Rome and led his XIII legion (the only one he had west of the Alps) to the Rubicon River, which divided Cisalpine Gaul from Italy proper. The governor of the province was forbidden by dictator Sulla’s rule from entering Italian territory with an army, and the governor’s crossing of the Rubicon with the legion signaled the start of a civil war.

All historians of his time cite Caesar’s apprehension and reflection at the Rubicon. According to Suetonius, Caesar said the following to his friends: “Even yet we may draw back; but once cross yon little bridge, and the whole issue is with the sword.” Then, miraculously, a tall, handsome man started playing the flute, grabbed a trumpet from one of the troops, splashed into the water, and swam to the other side while trumpeting the war signal.

Moving on, Caesar said, “Take we the course which the signs of the gods and the false dealing of our foes point out. The die is cast (Alea iacta est)“. The Greek historian Appian reports that a resolute Caesar told those in attendance, “My friends, stopping here will be the beginning of sorrows for me; crossing over will be such for all mankind.” Then, saying, “Let the die be cast,” Caesar “crossed with a rush like one inspired”. According to Plutarch, who also cites the same remark, Caesar originally spoke it in Greek.

Caesar made his way rapidly across Etruria and into Rome after crossing the Rubicon on January 10, 49 BC. This sparked yet another uprising during the latter years of the Roman Republic.

Verdict: He did.

4- Caesar seized power in Rome by force

Caesar crossed the Rubicon and marched toward Rome. As he marched into Italy, he encountered little in the way of real opposition; the Pompeians either surrendered or fled, while the smaller communities eagerly welcomed Caesar upon his arrival. Due to the quick advancement of the enemy, Pompey and his friends evacuated Rome, leaving behind the state treasury as well. With part of his army, Pompey marched to Greece. Seven more of his faithful troops were stationed in Spain.

Caesar’s policy of clementia (mercy) during the civil war, in which captives were routinely freed and no one was punished, was in direct response to the enemy’s strategy of clemency (pity). Caesar’s legions were open to recruits at will, and officers were frequently sent back to Pompey. This was in sharp contrast to the horrors done by both the Marians and the Sullans during the first Roman civil war and was unprecedented in the civil conflict that had plagued the Romans since the time of the Gracchus brothers (the final third of the second century BC). Caesar won every major battle, yet the civil war still lasted five years. The same dogged Pompeians who Caesar repeatedly crushed, only to free and forgive, turned against him.

The Civil War’s last fight took place at Munda, Spain, in March 45 BC. For a long time, nobody knew how everything would turn out. At some point, the lines of the Caesarians shook; suddenly, Caesar snatched his shield and raced forward to the enemy’s line. He took a barrage of spears before the ashamed centurions came to his aid. Caesar confessed that the fight at Munda was his toughest. He had often battled for success, but now, for the first time, he had to fight for his life.

Verdict: Correct.

5- Caesar had an affair with Cleopatra

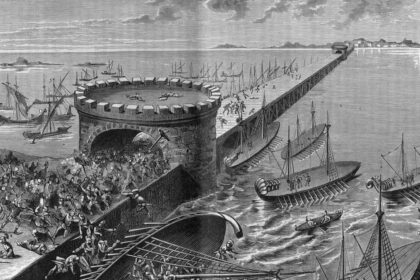

The meeting of Caesar and Cleopatra was tense. Dejected after Caesar’s historic victory against Pompey at the Battle of Pharsalus (48 BC), Pompey fled to Egypt in search of asylum, having previously shown excellent service to the late King Ptolemy Auletes of that country. Ptolemy XIII, King of Egypt at the tender age of 13, and his elder sister, Cleopatra VII, Queen of Egypt at the ripe old age of 20, were engaged in a bloody dynastic struggle for control of the Hellenistic state their father, Auletes, had founded. Ptolemy’s local royal guards made the decision to have Pompey killed to avoid a conflict with Caesar. They dispatched a boat for Pompey, and as soon as he got off the ship and onto the boat, he was murdered in front of his wife and son. Caesar, having accompanied Pompey to Alexandria, was appalled by the brutality and could not contain his emotions when he was presented with the severed head of his former opponent as a gift.

Caesar invaded Egypt with just two undermanned armies, yet the Romans nevertheless managed to seize key buildings like the royal palace in Alexandria. Egypt was understandably worried; Caesar intended to get revenge for the assassination of Pompey. There were signs of an impending war. The Roman said he wanted to resolve the succession dispute in Egypt and used this as an excuse to call for Cleopatra, who had either been kicked out of Alexandria or had fled the city herself. According to Plutarch, the girl was smuggled into the Roman camp away from her brother by having one of her friends carry her in a “bed bag.” This audacity on Cleopatra’s part impressed and fascinated Caesar. Herein lies the prologue to what would become one of the most widely read books in history.

The Egyptian queen was praised for her great beauty, loverliness, and sexuality by a wide range of authors from antiquity to the present era. Not surprisingly, the myth of “Cleopatra’s Egyptian nights” arose as a result of the widespread belief that she was a seductress, a demonic woman, and a charmer. According to Roman author Aurelius Victor from the fourth century, “many men paid with their lives for the possession of her for one night.” Cleopatra was the queen of Egypt, yet her flawless beauty is not reflected in antique busts or on coins commemorating her. Cleopatra was really appealing due to her brilliance and charisma. “The beauty of this woman was not what is called incomparable and strikes at first sight, but her treatment was distinguished by irresistible charm, and thus her appearance, combined with rare conviction of speech, had a huge charm, oozing in every word and oozing in every movement, firmly impressed in the soul,” wrote Plutarch. Her voice was like music to my ears; it was soothing and entrancing.

Cleopatra had an impressive education and mastered a number of tongues. Although she was the personification of the Egyptian goddess Isis and governed Egypt as its queen, the Greek-born Ptolemaic dynasty had dominated Egypt since the fall of Alexander the Great’s kingdom.

Caesar, unsurprisingly, sided with Cleopatra in her bid for Egypt’s crown and remained there for a significant amount of time. With the help of his newly arriving troops, Caesar quickly put down the anti-Roman uprising in Alexandria and ultimately beat Ptolemy’s forces. The young king was drowned in the Nile while trying to escape, and Cleopatra became ruler of Egypt. After that, the Roman commander was in no hurry to depart Egypt; instead, he and Cleopatra sailed down the Nile in a massive flotilla of 400 ships, taking in the sights and enjoying the finer things in life.

Even after Pompey’s death, the civil war continued. Caesar had to depart Egypt in the early summer of 47 BC because the Pompeians had grown stronger in the intervening months, and he didn’t want to risk losing the benefits of the Pharsalus triumph. Cleopatra gave birth to a son named Caesar (the Alexandrians dubbed him Caesarion, that is, “little Caesar”) not long after Caesar left, and the child, according to Suetonius, resembled his father in appearance and bearing.

Caesar invited Cleopatra to Rome in 46 BC, when he presented her with a sumptuous Tiber Riverside home and hosted a grand celebration in her honor. The purpose of the trip was to seal an alliance between Rome and Egypt, but the Egyptian queen ended up staying in Rome for quite some time. On the other hand, Caesar did not end his marriage to Calpurnia in order to wed Cleopatra. On the night before the Ides of March, he went to sleep for the last time.

Before leaving for the Senate on March 15, 1944, he spent some time with his wife, with whom he later bid farewell. Caesarion was never legally acknowledged as Caesar’s son, and Caesar did not name him as an heir in his testament. Suetonius adds that Caesar adored Cleopatra more than any other woman in his life.

Verdict: It’s true.

6- Caesar is the author of “I came; I saw; I conquered (Veni, vidi, vici)”

The Latin words sound even more powerful because they all start with the same letter: Veni, vidi, vici. This phrase was first used by the Caesarians and Pompeians in the civil war during the Pontic campaign (49–45 BC). During a time of internal instability in Rome, the Bosporan monarch Pharnaces began reclaiming the territories that had belonged to his vanquished father Mithridates at the hands of Pompey.

The majority of the Kingdom of Pontus was annexed by Rome and made into the province of Pontus in 63 BC. Pharnaces betrayed his father during those events, for which he received a part of his kingdom (the Bosporus Kingdom) from the Romans. But that wasn’t enough for Mithridates’s son, who had visions of reestablishing a mighty Pontic empire. As soon as Caesar found out that Pharnaces was against him, he left Egypt. On August 2, 47 BC, they fought near the city of Zela, but Caesar won. The iconic “lightning” phrase was created because the Pontic battle was over in a flash, in just five days.

Various ancient authors testify that it was Caesar who uttered it, though with some discrepancies. According to Plutarch, Caesar wrote these remarks in a letter to his friend Amantius (however, it appears that Plutarch misrepresented the true identity of Caesar’s friend, Gaius Matius). According to Appian, the phrase may be found in a Senate report. According to Suetonius, a plaque bearing the inscription “Veni, vidi, vici” was carried among the trophies as part of Caesar’s pontic portion of the triumph in 46 BC, while he was celebrating his quadruple triumph (over Gaul, Egypt, Pontus, and Africa). Suetonius claims that “by this, Caesar was not noting the events of the war but the swiftness of its completion.”

Verdict: Yes, these are the words of the great Roman.

7- Caesar was a dictator

It was officially Caesar’s reign over Rome from 45 BC forward. His dictatorial powers provided him with a legitimate foundation for ruling. In the autumn of 49 BC, Caesar assumed dictatorship for the first time; however, he lasted just 11 days. During that period, he oversaw elections, celebrations, and the introduction of many bills, including legislation to provide free food to the poor and partially forgive debts. Caesar was granted dictatorial powers permanently following the Battle of Pharsalus at the end of 48 BC, similar to those granted to dictator Sulla.

The Senate also bestowed upon Caesar, the victor, a variety of unprecedented honors, including the authority to unilaterally declare war and negotiate peace, to run for consular office for five years, and to preside over the Senate for the rest of his life. In ancient Rome, the tribunes of the people had the power of veto, meaning they could block any law or decree from taking effect. Only commoners could hold such a job. Moreover, Caesar was born into a wealthy family.

Then, the Roman dictator benefited from a new trick: the division of powers. The dictator was granted censorship powers after the battle of Thapsus in 46 BC, which meant that he was responsible for selecting senators. As Senate princeps, he had the honor of speaking and voting first in all Senate proceedings; his curule chair was positioned between the consuls, the two highest Roman judges. The Senate, a bottomless pit of adulation, bestowed the titles of Liberator, Father of the Fatherland, and Emperor upon the winner after the Battle of Munda.

Around the turn of the year 44 BC, Caesar’s cult of personality reached its pinnacle. His person was made sacred (sacro sanctus), games were held in his honor, and his statue was worshiped alongside that of the gods. In February 44 BC, Caesar’s rule became absolute. The dictator’s authority began to seem more and more like that of a monarch, but it was mixed with the Senate, the magistracy, and the people’s assembly, all of which had republican roots. Caesar didn’t want to wipe them out entirely; he just put them under his thumb.

The tyrant did more than just shore up his own power; he also instituted reforms that brought stability to Roman society. He reinstated the sculptures of Sulla and Pompey in the Senate as part of his stated philosophy of generosity. There were new restrictions on living lavishly. There was a lot of building done. Using his expertise in astronomy, Egyptian astronomer Sosigenes oversaw a reform of the calendar. Approximately 80,000 Caesarite soldiers, including many Pompeian exiles, were granted land. Citizenship was awarded to residents of several towns and provinces, and the Romanization of the conquered peoples proceeded quickly as a result.

Verdict: It’s true.

8- Caesar was treacherously murdered by his best friend, and before he died he said: “And you, Brutus? (Et tu, Brute?)”

At the start of the year 44 BC, Caesar was getting ready to launch a major offensive against the Parthian kingdom in the East. It was during this time that a plot was hatched against the dictator by a group that comprised several pardoned Pompeians, such as the commanders Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. Although many Caesarians, like Decimus Brutus and Trebonius, opposed the dictator, there were also numerous Caesarians who owed their careers and fortunes to the dictator. Some people joined the conspirators for their own selfish purposes, but the vast majority did so out of a genuine concern that Caesar’s rule might devolve into a dictatorship.

During the Lupercalia celebration on February 15, 44, an occurrence took place that was very upsetting to certain segments of Roman society. Marc Antony, a Caesar ally and general, made an embarrassing effort to publicly present the dictator with a laurel wreath. Plutarch says, “Liquid acclaim surged throughout the populace, as had been arranged in preparation.” As one man put it, “When Caesar rejected the crown, all the people applauded.” This occurred again when Antony attempted the tactic a second time. As Caesar saw the crowd’s response, he gave the order for the crown to be transported to the Capitol’s Jupiter Temple. They inscribed “If only you were alive!” and “Oh, if only you were with us today” on a statue of Marcus Junius Brutus’ semi-legendary ancestor, Lucius Junius Brutus, one of the founders of the Roman Republic and a subverter of the last king, Tarquinius the Proud.

When Mark Junius Brutus was praetor (in 44), he got messages asking him something to the effect of, “Are you sleeping, Brutus?” “You’re not the genuine Brutus,” he said. Now, a word or two about Brutus, the man who came to symbolize the plot. Perhaps it was because his mother, Servilia, had been the dictator’s lover in the past, but Caesar had a warm place for him from the beginning. An even more improbable theory is that Brutus was really Caesar’s son, as suggested by certain ancient writers. In 85 BC, Brutus entered the world. Caesar was about 16 at the time, so he and Servilia didn’t really start dating until much later. Brutus initially sided with Pompey, but when the Pompeians were defeated at Pharsalus, he surrendered to Caesar and was recognized as one of his “closest allies.”

Brutus had a fruitful political career in the new era, rising to the positions of governor of Cisalpine Gaul (46 BC), praetor of Rome (44 BC), and consul (41 BC). However, this did not prevent Brutus from writing a eulogy for Caesar’s opponent, Cato, in 45 or from liking Cato himself. After divorcing Claudia Pulchera, Brutus married Cato’s daughter, Portia.

According to Plutarch, the other conspirators asked Cassius to recruit Brutus because they wanted a symbolic (because of his name) figure on their side.

On March 15, 44, the Ides of March, the conspirators met in the Senate one more time to plot Caesar’s assassination before launching an invasion of the Parthian Empire. Calpurnia, the dictator’s wife, had a nightmare in which she saw her dead husband, but Caesar nevertheless went to the Senate the day thereafter, despite the dire warnings and predictions being circulated about him. When the dictator ran across the fortune teller Spurinna, who had previously warned him of the peril that awaited him on the Ides of March, he joked that the Ides had already arrived. His reply was, “Yes, they have arrived, but they have not yet gone.”

Caesar was given a scroll by a bystander that revealed the murder plot and strategy, but the dictator didn’t have time to read it before he entered the Curia of Pompey, where the Senate was holding a conference. A number of senators encircled the dictator’s chair, their daggers glinting in the air. Senators who were unaware of the plot were so terrified that they were unable to take any defensive action or even raise their voices. It was decided that all the conspirators would take part in the murder and taste the sacrifice blood, so they all encircled him while brandishing bare daggers. Whenever he opened his eyes, he was struck with the strokes of swords aimed at his face and eyes. Caesar, who was badly injured, propped himself up against the base of Pompey’s statue, leaving a bloody mark.

The ancient authors who described this sad event all underlined Caesar’s emotional reaction to seeing Brutus among the killers. Seeing Brutus with a bare sword, Caesar flung his toga over his head and exposed himself to the blows, as Plutarch recounts, citing “some authors” who have not lived. Immediately before he struck, Dion Cassius claims the tyrant said in Greek, “And you, child!” Suetonius, citing some sources, states that Julius Caesar, upon being stabbed by Brutus, said in Greek, “And you, my child!” (καὶ σὺ τέκvον). However, “And you, Brute” (Et tu, Brute) is not cited anywhere. This line was first used by Shakespeare in his play Julius Caesar, where it was spoken by the dying tyrant.

According to doctor Antistius, the dictator had twenty-three stab wounds, but only one in the chest proved fatal. Whoever did it remains a mystery.

Brutus and Cassius, who were in charge of the plot, killed themselves two years after Antony and Octavian beat them at the Battle of Philippi.

Verdict: This is only partly true; Caesar considered Brutus his friend, but he did not utter these words.

9- Caesar was a good writer

Caesar was more than just a great leader; he was also a gifted writer and orator. In his youth, Caesar produced The Praise of Hercules, the play Oedipus, and the Collected Sayings, but Emperor Augustus forbade their publication, despite Suetonius’ claims that he had a passion for literature from a young age. As an adult, Caesar wrote his treatise on grammar, On Analogy, which was highly praised by Aulus Gellius, the author of the Attic Nights (2nd century). This academic work has not been passed on to us.

It is well known that Caesar took part in the debate between the analogists, who were close to him in spirit and emphasized that rules are more important than exceptions, and the anomalists, who paid a lot of attention to irregularities and deviations from the norm based on Latin linguistic norms. Sadly, none of his other writings, notably the poem The Way, have been preserved. The Way is an astronomical book written with Sosigenes and a political tract. “The Way,” a poetry collection, and “Anticato,” a political book, are both polemical responses to Cicero’s panegyric Cato.

Thankfully, both Caesar’s Notes on the Gallic War and his Notes on the Civil War have made it through the ages intact. The events of 52 BC, with Vercingetorix’s capitulation, mark the conclusion of the first seven volumes of Notes on the Gallic War, which detail the conquest of Gaul and the two forays into Britain. Caesar’s companion and comrade in arms, Aulus Hirtius, resumed his description of the wars in 51 and 50. Caesar was unable to complete “Notes on the Civil War,” since the third volume is broken up by the narrative of his arrival in Egypt and the Roman conquest of the city’s most significant landmarks. No one knows for sure who penned the sequel that concluded the Civil War narrative. Since ancient times, people have argued about who wrote these works. Some say it was Gaius Oppius, while others say it was Aulus Hirtius.

Intriguingly, Caesar never refers to himself in the first person, preferring instead to talk about himself in the third person to seem more objective and convincing. Nevertheless, despite his Notes’ bias, they are a valuable historical resource, and in certain areas (the history, religion, and culture of pre-Roman Gaul), they are the only available information at all. Plus, it’s really good Latin; Caesar uses straightforward language that manages to be both eloquent and moving. Every graduate of a classical gymnasium remembers the first phrase of Caesar’s Notes on the Gallic War with its charming rhythm and euphony, which unfortunately disappear in translation: Gallia est omnis divisa in partses tres, quarum unam incolunt Belgae, aliam Aquitani, tertiam qui ipsorum lingua Celtae, nostra Galli appellantur…

Verdict: Undeniable.

10- Caesar wore a laurel wreath to hide his bald head

Suetonius describes Caesar as follows: “He was tall, fair-skinned, and well built; his face was a little full, and his eyes were black and lively.” Until the end of his life, when he began to have unexpected fainting episodes and night terrors and twice had fits of hysteria in the middle of courses, his health was outstanding. Caesar was meticulous about his personal grooming and took good care of his physique, even going so far as to remove his hair despite criticism from moralists of the day. The historian Suetonius reports that Caesar hated his bald head because of its ugliness. This is why he would always proudly wear the laurel wreath despite his thinning hair by combing it from the crown to the forehead.

Verdict: It’s true.

11- Caesar could do three things at the same time

A number of ancient sources attest to Caesar’s problem-solving prowess and claim that he could handle any crisis with a single swift stroke of his sword. During the Gallic Wars, Caesar’s companions and soldiers saw him seated on a horse while he dictated letters to many scribes at once, as described by Plutarch. According to Suetonius, Caesar would read letters, messages, and other papers or write replies to them while watching gladiatorial duels. Pliny the Elder said that Caesar had “most excellent in strength of mind”(animi vigore praestantissimum). This meant that when he wasn’t busy with other things, he could dictate up to seven letters at once.

The great Roman may have simply switched from one task to another, but the impression is that he could multitask with ease.

Verdict: It’s true.

12- The word “king” also comes from Caesar

In addition to the “Tsar” of Russia, there was also the “Kaiser” of Germany. Imperial Rome added “Caesar” to the emperor’s titulature alongside “Augustus.” Emperor Diocletian’s tetrarchy, which split the Roman Empire into four pieces at the close of the fourth century, included two senior rulers named “Augustus” and their subordinates named “Caesar.”

Both the Latin name Caesar and the Greek name Kαῖσαρ were widely adopted by the many nations and cultures in the area, including those who would eventually destroy the Roman Empire. Many Slavic peoples, according to Max Pasmer’s “Etymological Dictionary of the Russian Language,” got the title “Káisar” from the leaders of the Germanic tribe of Goths. Hence Old Russian and Old Slavonic cesar, Serbo-Croatian cesar, Slovenian césar, Czech císař, Slovak cisár, and Polish cesarz. Then Old Russian tsesar was abbreviated to tsesar, and then became tsar.

Tsars were commonly used to refer to the emperors of the Holy Roman Empire and Byzantium (hence Tsargrad, as Rus called Constantinople), biblical rulers, and Mongol khans in Old Russian and later in medieval tradition; unofficially, this title was tried on and Old Russian princes, and then the rulers of Moscow. Ivan IV was formally anointed Tsar of “all Russia” in 1547, at which time the term became widely used.

Verdict: It is true.

13- Caesar came up with the salad of the same name

There is very little direct connection between the salad and the Roman tyrant. The Italian-American chef Caesar Cardini, who in the 1920s and 1940s maintained a string of successful restaurants in Tijuana and San Diego (Baja California), is credited with creating the salad. Cesare Cardini, who immigrated to the United States from Italy in 1913 and bore the name of the Roman emperor, was the creator of one of America’s most beloved meals.

Rosa Cardini recalls that her father created this salad on July 4, 1924, when the kitchen ran out of food during the Independence Day celebration at the Caesar’s Place restaurant in the hotel of the same name in Tijuana.

Wallis Simpson, the Duchess of Windsor, made Caesar salad popular in Europe thanks to her frequent orders of the dish at the continent’s finest establishments during her many trips with the Duke of Windsor, the former king of Great Britain, Edward VIII, from whom she was divorced after their mesalliance led to his abdication. There is, however, another theory that Italian chef Giacomo Junia created the salad in Chicago in 1903 and named it after the great Roman since he was a fan of the guy.

Verdict: It’s not true.

Bibliography:

- Suetonius Tranquillus Gaius. Life of the Twelve Caesars. Divine Julius. Divine Augustus. Translated from the Latin by M. L. Gasparov.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History. Translated by B.A. Starostin.

- Plutarch. Comparative Biographies. Caesar, Pompey, Cicero, Mark Antony, Brutus. Ed. С. S. Averintsev, M. L. Gasparov, S. P. Markish.

- Gaius Julius Caesar. Notes of Julius Caesar and his successors. The Gallic War. Civil War. The war of Alexandria. The African War. Translated from Latin by M. M. Pokrovsky.

- Egorov A. B. Antony and Cleopatra. Rome and Egypt: the Encounter of Civilizations. SPb., 2012.

- Egorov A.B. Julius Caesar. Political Biography. SPb., 2014.

- Mommsen T. History of Rome. Т. 2-3. SPb., 1994.

- Utchenko S. L. Julius Caesar. М., 1976.

- Fasmer M. Etymological dictionary of the Russian language.

- Lurie S. The Changing Motives of Cesarean Section: From the Ancient World to the Twenty-First Century. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol. 271. 2005.