- The Mushussu is a mythological snake-dragon from Mesopotamian mythology.

- It has the body of a lion, the tail of a snake, and a long neck.

- Mushussu was worshiped as a symbol of protection and associated with various deities.

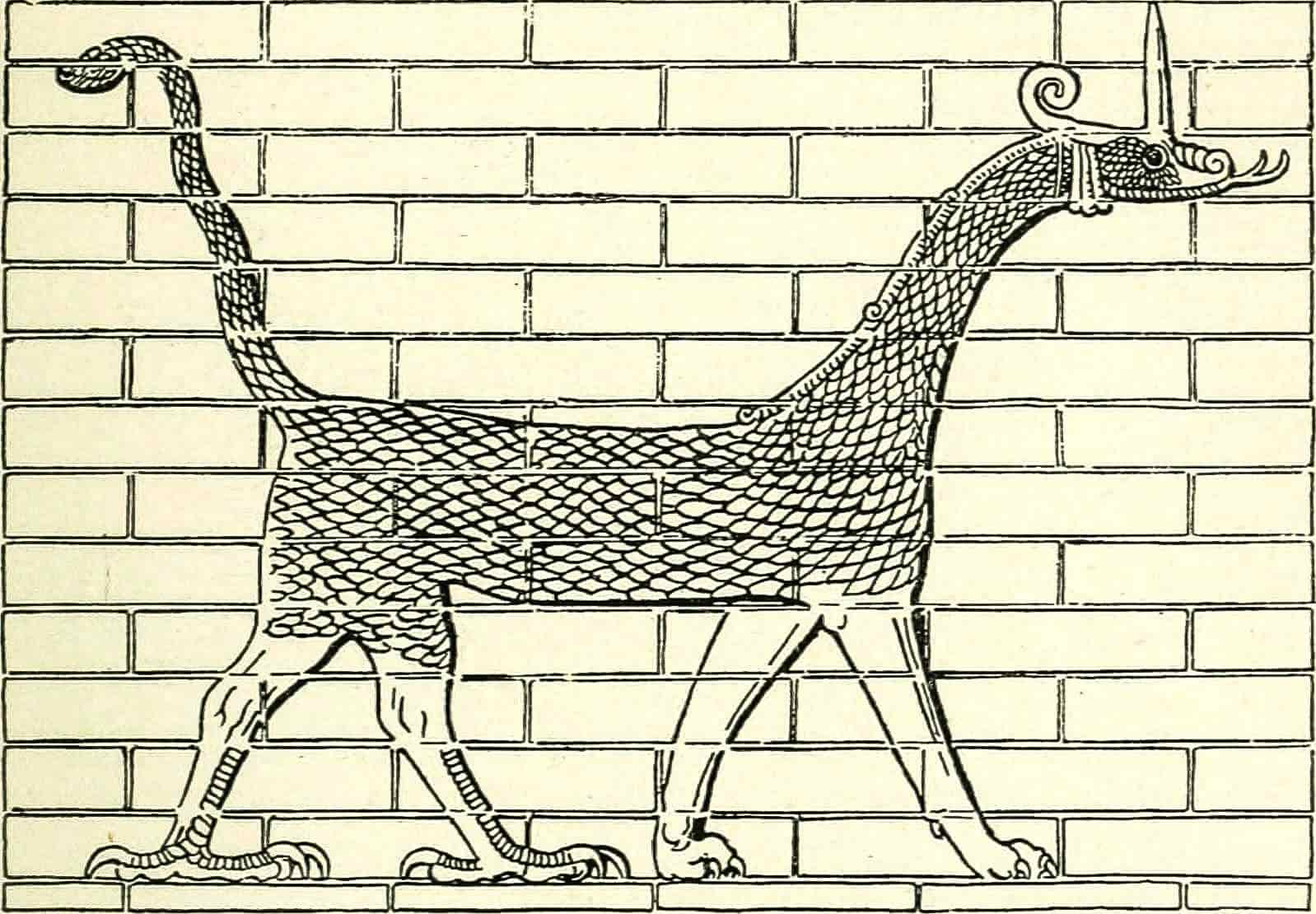

Known chiefly from its portrayal on the procession route leading to the Gate of Ishtar in Babylon, the Mushussu (Akkadian: Mušḫuššu, catfish; Sumerian: Muš.HUŠ) is a mythological snake-dragon from Mesopotamian mythology and a holy animal of many gods. The snake-dragon may have first been mentioned during the Early Dynastic era (about 2800–2350 BCE). The Hellenistic era marks the last documentation of Mushussu.

What Does Mushussu Mean?

The Sumerian word MUŠ is the source of the Akkadian term Mushussu (MUŠ (‘snake’) + HUŠ (‘furious’). The meaning of Mushussu as “furious snake” has been widely recognized for a long time.

The name was once misread as Sirrusu because of the ambiguity of cuneiform writing, but this reading is now considered incorrect.

The second part might be interpreted as RUŠ, which meant ‘red’ in the Sumerian language, lending credence to the alternative meaning of “red snake.” Because the HUŠ symbol means “furious” or “reddish,” depending on context.

How Did Mushussu Look Like?

It has the body of a lion but the tail of a snake and a very long neck.

The creature’s appearance has evolved greatly over the ages. The Old Akkadian era (2350–2210 BCE) is the source of Mushussu’s classical form. However, the Early Dynastic era has one of the oldest representations of this mythical serpent-dragon.

It has the body of a lion but the tail of a snake and a very long neck. Even though the snake-dragon on an ancient Eshnunna (a Sumerian city-state) relief has a dragon’s head and horns, its hind feet are still those of a lion.

A winged version of the snake-dragon, complete with a scorpion’s sting, gained popularity in Lagash, an ancient city-state in Iraq, under the reign of Gudea (r. 2144–2124 BC). It is shown as a winged hybrid with the lion’s forepaws and the clawed feet of a hyena on Gudea’s Vase, which dates back to circa 2100 BCE. It has two horns on its head and many strands of hair that surround it.

Its First Known Depiction

The lion symbols gradually gave way to the snake ones. The first known depictions of Mushussu on kudurru (a type of Babylonian stele) date to the Middle Babylonian era (ca. 1595–1155 BCE). The snake-dragon already has the long neck, serpent’s head, and forked reptile tongue seen in subsequent depictions.

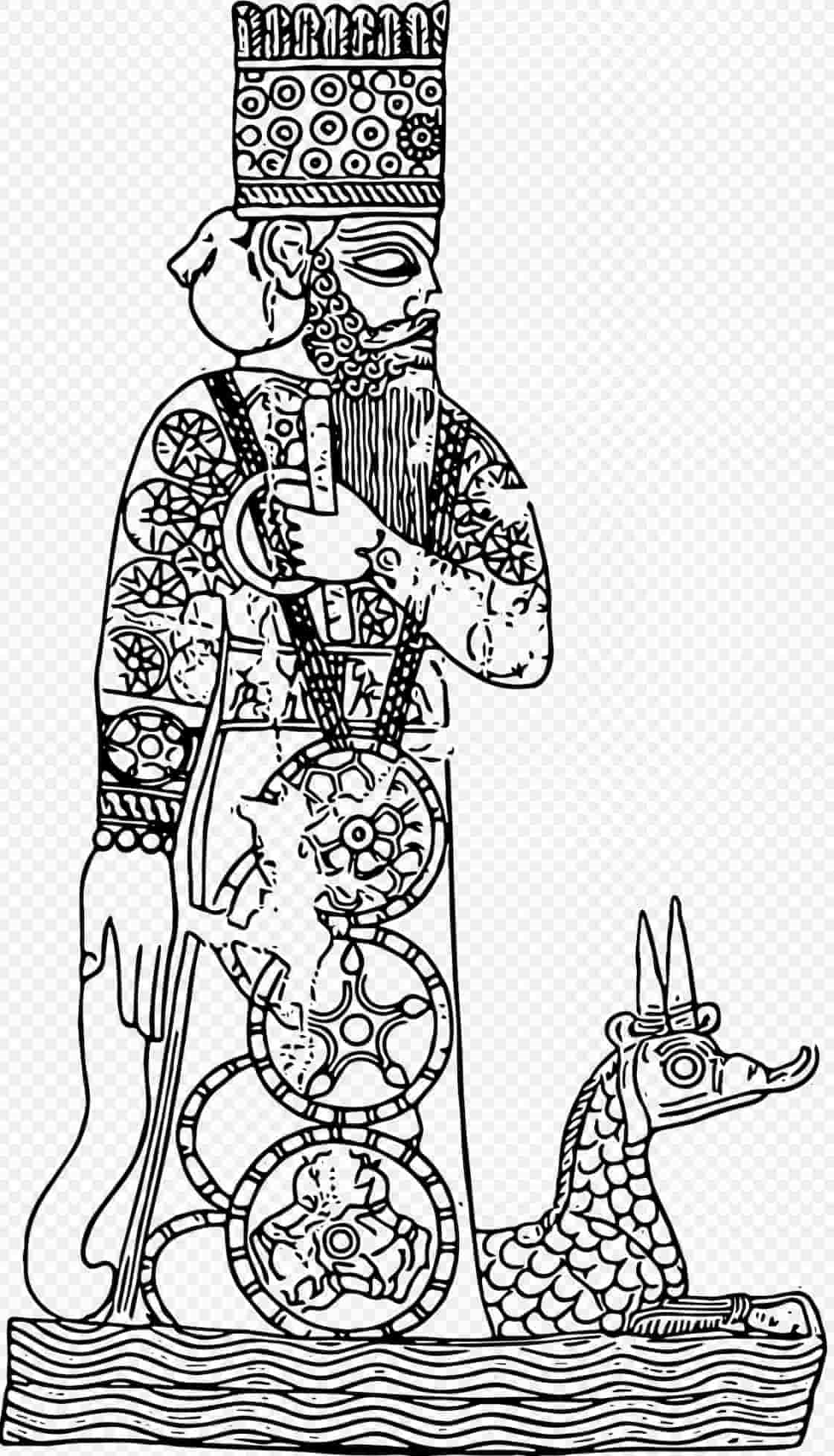

During the Middle Babylonian era, the deity Marduk adopted the Mushussu as his personal mount. A stele of King Meli-Shipak from this time period depicts the snake-dragon in its distinctive position at the foot of the god. Later, during the reign of King Marduk-zakir-shumi I (c. 9th century BCE), the same design was utilized on a lapis lazuli cylinder seal.

On the Ishtar Gate

During the Neo-Assyrian era (934–610 BCE), Mushussu (or Mushkhushshu) was often represented without horns or with a feathered tail.

The image of Mushussu is most associated with the Ishtar Gate. Archaeologist Robert Koldewey first identified the connection between the ruins and the Ishtar Gate between 1902 and 1914. He matched the newly unearthed pictures to the king’s inscription, which depicted the bull and dragon reliefs that adorned the Ishtar Gate.

The Myth of Mushussu

Mushussu was never seen among the pantheon of gods or devils. The “DINGIR” determinative, a Sumerian word to denote a divine being, is not actually prefixed to the name of this entity in literature.

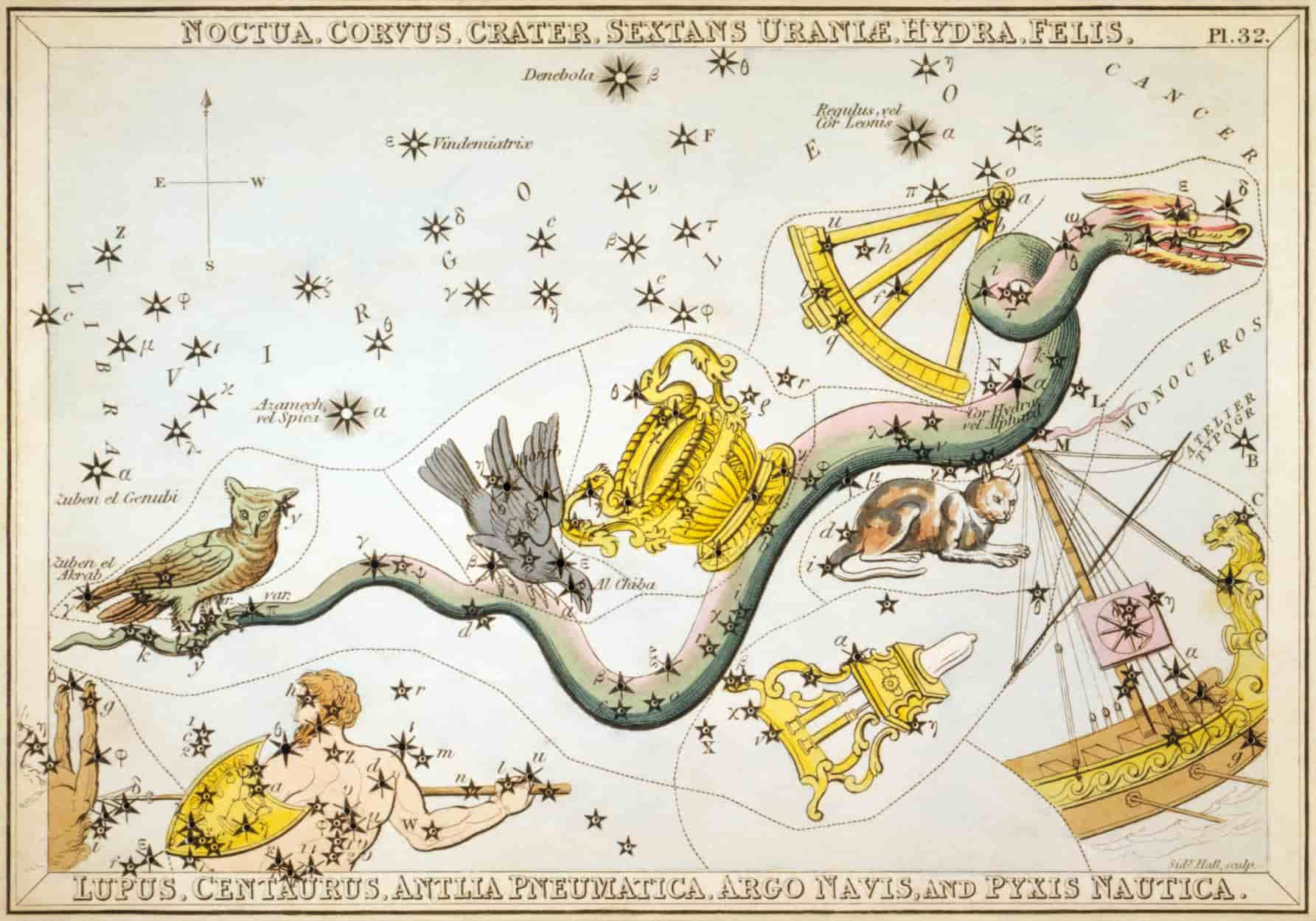

The only time this term comes before Mushussu is when talking about the constellation of the same name. On the one hand, it is shown as a creature having ties to several deities in Mesopotamian mythology. On the other hand, Mushussu is just a protecting entity with no particular divine ties.

The god Mushussu represented the element of water, and it is often considered a gender-neutral entity. Tiamat, the sea goddess, fashioned the serpent-dragon as one of the creatures she sent against Marduk. In the ancient texts, it is called “the monster of Lahamu.”

Mushussu is included among the group of supernatural entities called ina libbi (Akkadian for “inside”) in the Babylonian Map of the World, suggesting that it is located in the ocean.

Historically, the snake-dragon was worshiped as a symbol of Eshnunna’s protector deities, the chthonic deity Ninazu, and his son Ningishzida.

Tishpak, the new ruler of Mushussu, took over as city guard at the end of the Early Dynastic era. Tishpak is seen riding the snake-dragon in the newly found Old Akkadian-era artwork at Eshnunna. The snake-dragon’s apparent status as a messenger of chthonic deities suggests that its venomous attacks were seen as an act of obedience to divine order. Elamites also had an impact on the city-state Eshnunna (which was situated in the Trans-Tigris area), hence the deities worshiped there had snake characteristics.

Origin of Mushussu Worshipping

It’s unclear why or when the monster Mushussu started being worshiped by the Babylonians. This probably happened soon after Hammurabi conquered Ennunna and instituted the worship of Tiapak.

In an inscription by Kassite king Agum II, Mushussu is said to have been connected to Marduk for the first time; however, the reliability of this source is in dispute.

Mushussu is seen in art with Marduk and his son Nabu during the Kassite era (the Middle Babylonian era). The snake-dragon is often shown next to other icons of these deities, such as spades and scepters. Following Assyria’s ultimate conquest of Babylon in 689 BCE, the deity Ashur was associated with the figure of Mushussu.

Monsters like the “venomous snake,” basmu (bashmu), were sometimes represented alongside gods linked with Mushussu. During the Kassite era, basmu replaced Mushussu as Tishpak’s emblem in written sources.

Mushussu may have been part of the Urukian zodiac calendar created under the Seleucid dynasty. It shows a hero facing off against a mysterious beast that, to some scholars’ eyes, seems like a snake. Although the identity of the pictured dragon remains a mystery, there is some speculation that the beast is not a literal dragon at all but rather a metaphor for disorder.

Function of Worshipping Mushussu

Mushussu statues have been used as “guardians” of houses’ front doors since the late 3rd century BCE. The earliest known example was discovered at the Ninurta temple in Girsu, an ancient Sumerian city. Clay plaques with its likeness began appearing in the Old Babylonian era to serve as amulets for individual residences.

Mushussu images on the Ishtar Gate serve a similar purpose. The purpose of these sculpted snake-dragons was to poison the enemies of the Sumerians. This is literally from a discovered inscription from the reign of King Neriglissar (560–556 BCE).

Miniature apotropaic figures of Mushussu dating back to the Neo-Assyrian era have also been discovered.

Constellation

During the time of the Old Babylonians, a trio of stars was given the same name as the serpent-dragon: MULMUŠ or MUŠL dMUŠ. In late Babylonian astrological literature, chthonic deities like Ereshkigal and Ningishzida were linked to the constellation Hydra, which has a parallel in Greek astrology. The Uruk zodiacal calendar from the Seleucid era has a picture of this constellation.

Mushussu in Christianity

The Mesopotamian Mushussu may have had an influence on the writers of the Bible. The story of Marduk’s conflict with Tiamat and her army of monsters is similar to what is told in the Book of Ezekiel (32:2–8). The religion of a giant snake is mentioned by Daniel (14:23–28) in the Book of Daniel.

The Mesopotamian Mushussu may have served as inspiration for various passages in the Bible. A story from the Enuma Elis, in which Marduk faces off against Tiamat and an army of monsters she has produced, is echoed in Ezekiel (32:2–8). However, the worship of a giant snake is mentioned in Daniel 41:14–23, which describes the religion of the Babylonians.