- The Crusades Were the First Confrontation Between Christians and Muslims

- The Crusaders Only Fought Muslims

- Only Knights Went on Crusades to the Holy Land

- Knights Went on Crusades Solely for Profit

- The Crusades Awakened Religious Intolerance

- The Era of the Crusades Brought Only Death, Destruction, and Disease

Over nine hundred years ago, thousands of Europeans set out to reclaim the Holy Sepulchre — a term that symbolically referred to Jerusalem and the surrounding Holy Land. Since then, many myths and legends have formed around the crusaders and their wars.

The Crusades Were the First Confrontation Between Christians and Muslims

To understand why this is not the case, we need to look at the events that preceded the Crusades.

By 1096, the beginning of the Crusades, the Reconquista — the process of reclaiming the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal) from the Moors who had seized it — had already been ongoing for more than three centuries. The Moors were North African tribes who had embraced Islam in the 7th century. In just seven years (from 711 to 718), the Moors defeated the Visigothic Kingdom, conquered almost all of the Pyrenees, and even invaded southern France. The Europeans (the inhabitants of Leon, Castile, Navarre, and Aragon, who would later become unified Spain) would only fully reclaim these lands in 1492.

Jerusalem itself had been under Muslim control for more than four centuries at the time of the First Crusade, having been seized from the Byzantine Empire. Both Arabs and, later, Seljuk Turks had been pushing back the Byzantines since the 7th century. Gradually, the Byzantines lost their territories (Egypt, the African coast of the Mediterranean, Palestine, Syria) and eventually retained only part of Asia Minor and Constantinople. This brought Byzantine Greek civilization to the brink of catastrophe by the end of the 11th century.

Meanwhile, the remnants of the Arab Caliphate continued their expansion in the Mediterranean. For instance, in the 11th century, Europeans were reclaiming Sicily from the Arabs. In 1074, more than 20 years before the beginning of the Crusader movement, Pope Gregory VII even planned a holy war against the Muslims.

Therefore, the Crusades cannot be considered the first clash between Muslims and Christians. This idea was already in the air and was realized in the sermons of Pope Urban II in the French city of Clermont in 1096.

The Crusaders Only Fought Muslims

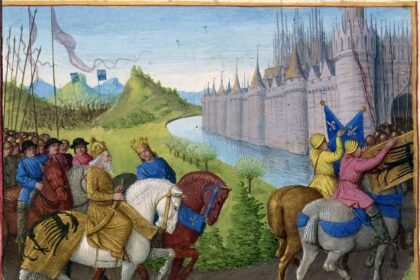

The classical Crusades are considered to be the expeditions of European knights to the Middle East and the surrounding territories from 1096 to 1272. However, there were many wars sanctioned by the Catholic Church that were fought in the south, north, and east of Europe itself. From the mid-12th century, Crusades were organized not only against Muslims. Pagans, heretics, Orthodox Christians, and even other Catholics were declared enemies of the Crusaders.

The Albigensian Crusade from 1209 to 1229 was directed against the Cathar heretics — the Albigensian sect — who did not recognize the Catholic Church.

The Crusades against southern Italy and Sicily from 1255 to 1266 were initially directed against fellow Catholics. The Pope, who sought to unite all of Italy under his authority, claimed that the Catholics living there were “worse than pagans.” Thus, the holy war became a political tool of the Roman pontiff.

There is also a well-known movement of German knightly orders against the followers of pagan cults in the Baltic region. In the 12th and 13th centuries, Crusades were organized against the Polabian Slavs, Finns, Karelians, Estonians, Lithuanians, and other local tribes. The Crusaders even reached the northern Russian lands and fought against Alexander Nevsky, among others.

In the 15th century, the Roman Catholic Church sanctioned Crusades against its opponents — the Hussites in Bohemia and the Ottoman Empire. The last Crusade could be considered the campaign of the Holy League of European states against the Ottoman Empire from 1684 to 1699.

Executions of the “undesirable” were also carried out without papal sanction. The First Crusade began with mass pogroms of Jews in northern Germany and France. The brutality of this persecution was such that many Jews chose to kill themselves rather than fall into the hands of the “soldiers of Christ.” It was a common practice to offer a choice between death and baptism.

The Crusaders behaved no less shamefully towards the Christians of the Middle East, of whom there were many. The fact is that by that time, a clear division between the Western and Eastern branches of Christianity had already emerged. Therefore, it is not surprising that the Europeans considered the Orthodox to be barbarian pagans. For example, after capturing Antioch in 1098 following a tough siege, the participants of the First Crusade conducted a massacre in the city, sparing neither Muslims, Christians, nor Jews.

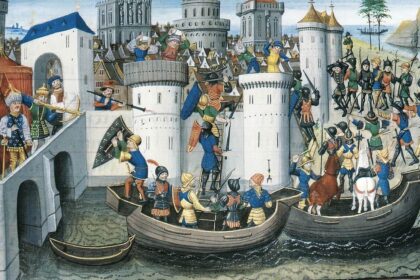

The participants of the Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) even captured Constantinople instead of heading to Egypt. The city was plundered, and many treasures and relics were taken to Europe. As can be seen, the “civilized” Greeks (Byzantines) were little different from the “barbarians” to the Crusaders.

Only Knights Went on Crusades to the Holy Land

In reality, almost all social strata of medieval Europe participated in the Crusades, from kings to paupers and even children.

The very first Christian campaign (not to be confused with the First Crusade) was the People’s Crusade in 1096, also known as the Peasants’ Crusade or the Crusade of the Poor. Inspired by the sermons of Peter the Hermit and the speeches of Pope Urban II (who suggested joining the “holy army” to atone for one’s sins), a large crowd of ordinary people and a small number of knights (a total of up to 100,000 people, including women and children) did not wait for the official start of the Crusade. They didn’t even bring supplies with them. This force invaded the Seljuk lands and was defeated — almost all the participants perished.

Subsequently, peasants repeatedly organized their own “Crusades,” for which the popes even excommunicated the participants from the Church, and their own kings crushed their armies.

In 1212, a movement began in Europe that became known as the Children’s Crusade. It all started when a teenager named Stephen from Cloyes claimed that Christ had appeared to him and commanded him to liberate the Holy Land. Stephen was supposed to do this through the power of the pure prayers of innocent children’s souls. A similar “prophet” also appeared in the French lands. As a result, up to 30,000 children from France and Germany set out following Stephen, believing his sermons. They barely made it to Marseille, where they boarded seven ships provided by local merchants. The children were then taken into slavery in Africa. However, today many historians doubt that the participants in this crusade were truly children — more likely, they were adolescents and young people.

Of course, the Crusades mentioned above were not organized with the pope’s approval, making them somewhat unofficial. But they cannot be excluded from the Crusader movement either.

Women also participated in the Crusades. For example, in the Seventh Crusade, 42 women traveled on one of the ships along with 411 men. Some traveled with their husbands, while others — often widows — went independently. This gave them the opportunity, like men, to see the world and “save their souls” after prayers in the Holy Land.

Knights Went on Crusades Solely for Profit

For a long time, it was believed that the main participants in the Crusades were the younger sons of European feudal lords—knights who did not inherit wealth. Consequently, their primary motivation was thought to be filling their pockets with gold.

In reality, such a simplification is difficult to take seriously. Many of the Crusaders were wealthy individuals, and participating in a holy war was expensive and rarely profitable. A knight had to arm himself and equip his companions and servants. Moreover, throughout the journey to the Holy Land, they needed food and shelter. The overland journey alone took months.

Often, the entire family participated in raising these funds. Knights frequently mortgaged or sold their property.

For example, the leader of the First Crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon, mortgaged his family castle. Most of the time, Crusaders returned home empty-handed or with relics, which they donated to monasteries. However, participating in a “righteous cause” significantly raised the family’s prestige in the eyes of other nobility. Therefore, a surviving single Crusader could hope for a profitable marriage.

To reach the Holy Land by sea, they also had to spend money: to “book” a place on a ship for themselves (as well as for their retinue and horses, if they had any) or to buy provisions. At the same time, no one could guarantee the safety of either the sea or land journey. Crusaders died in shipwrecks, drowned while crossing rivers, or succumbed to disease and exhaustion.

The territories seized in the Holy Land not only failed to generate profit but almost entirely depended on European resources. To maintain them, kings introduced new taxes. This is how the “Saladin Tithe” came about, named after the ruler of Syria and Egypt who recaptured Jerusalem from the Crusaders.

The overseas possessions were literally draining money. The Seventh Crusade of Louis IX cost 36 times more than the annual income of the French crown.

The Crusades Awakened Religious Intolerance

Despite the successes of the Crusaders, initially, there was no rush to declare jihad against the incoming Christians in the East, although Jerusalem was also an important city for Muslims. The fact is that Muslim rulers were more occupied with conflicts among themselves than with the Crusaders. It got to the point where they invited Christians to participate in their quarrels. Only when the Middle East began to unite under the authority of a single ruler (for example, Nur ad-Din or Saladin) did Muslims start to offer genuine resistance.

However, this confrontation cannot be called the cause of the emergence of religious intolerance. Much earlier, in 1009, the Egyptian Caliph Al-Hakim ordered the destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and initiated persecution of Christians and Jews—with killings and forced conversions to Islam. Therefore, it is naive to say that the Crusades caused Islamic extremism.

The situation with the Crusaders seems somewhat different at first glance.

For medieval Europe, the Crusades were the first instance where war was not only not considered a sinful act but was presented as a righteous and holy endeavor.

Only 30 years earlier, after the Battle of Hastings in 1066, Norman bishops imposed penance—a form of ecclesiastical censure and punishment—on their warriors (who, by the way, had won).

Overall, despite the wars, Muslims and Christians in the Middle East coexisted peacefully with each other most of the time. While Jerusalem was under Arab control, Christian pilgrims could freely venerate their holy sites, which were not destroyed. Muslims were also tolerant of local Christians, imposing only a special tax on them. A similar situation existed in the Crusader states, where followers of Islam made up the majority of the population.

The Era of the Crusades Brought Only Death, Destruction, and Disease

The Crusades claimed many lives and caused much suffering, but they also had beneficial consequences for societal development.

Since wars in distant territories required a constant supply of provisions, this stimulated the development of shipbuilding. Sailing across the Mediterranean Sea became safer and more active, as shipwrecks became less frequent. Many products (saffron, lemon, apricot, sugar, rice) and materials (chintz, muslin, silk) from the East reached Europe. After the Crusades, interest in travel grew significantly in Europe.

For the first time since the Roman Empire, large groups of people set off not as pilgrims or traders, but out of interest in the unknown.

The Crusades significantly expanded the cognitive horizon of Europeans, who became acquainted with other peoples, cultures, and countries. This movement helped accumulate vast knowledge and explore significant territories.

The Fifth Crusade (1217–1221) laid the foundation for the first medieval expeditions to Central Asia and the Far East.

Thanks to the Crusades, Europeans were able to access works from around the world that had been carefully collected by Muslims. Numerous texts by ancient scholars and philosophers, lost in Europe, were returned thanks to Arabic translations.

Medieval science acquired an unprecedented amount of knowledge in geography, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, history, and linguistics. It is believed that the Crusaders thus paved the way for medieval Europe to enter the Renaissance.

However, it should not be forgotten that all of this was achieved at the cost of the economic devastation of modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine. Many cities and settlements were destroyed or fell into decline, and vast forests were cut down due to numerous sieges. Traders and artisans, for which these places were once famous, relocated to Egypt.

It took participants of the First Crusade, which lasted from 1096 to 1099, three years to capture Jerusalem. After that, there were eight more large-scale expeditions. The Crusaders held the lands of Palestine and the Levant for nearly 200 years, until 1291, when they were finally defeated and expelled from the Holy Land.

Around the Crusading movement, many legends were formed, creating a kind of romantic aura. But in reality, as always, everything turned out to be somewhat more complicated.