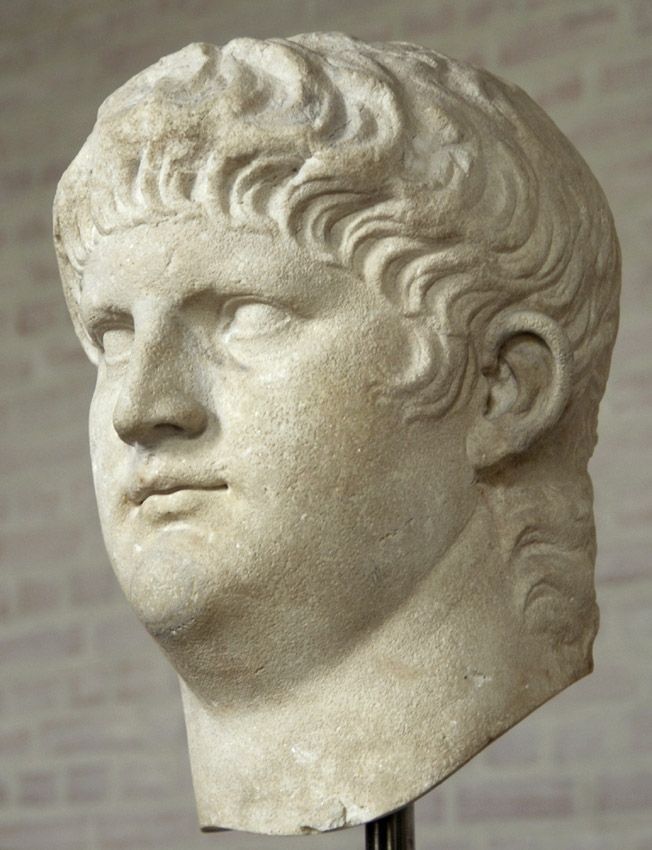

Nero (Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus)’s birth date is traditionally accepted to be December 15th, 37 AD, at Antium, while his death date is conventionally accepted to be June 9th, 68 AD, in Rome. Emperor Vespasian was the fifth and last ruler of the Roman Empire under the Julio-Claudian Dynasty. Nero seems like a complex figure since he has been called both a brutal ruler and a poet. Yet the Emperor’s capricious nature continues to captivate. The majority of what is known about Nero comes from biographies published 40 years after the events, such as those by Suetonius and Tacitus.

Childhood under Caligula

The true name of Nero is Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, and he was born to Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and Agrippina the Younger, the sister of Caligula. Caligula assumed power on March 16, 37 AD, when he was 24 years old. In the event that Nero’s uncle did not produce a male successor, Nero might assume the throne. But when it came to their brother Caligula, Agrippina and her sisters were quite close. So, Caligula was greatly influenced by them.

As a matter of fact, Nero was born to a prominent mother. Nero did not go with his mother when she was banished to the Pontine Islands because of her role in a plot against Caligula. In 40 AD, Nero’s father passed away. Caligula, his wife, and their daughter were all murdered in a plot that was hatched on January 24, 41 AD. So, the winds shifted in favor of Nero when Caligula’s successor, Claudius, called Agrippina back to Rome.

Claudius adopts Nero

But Nero had little chance of succeeding Claudius as Emperor. The Emperor had two children: the heir apparent Octavia, born in 40 AD, and Britannicus, born in 41 AD. But the rules changed with Agrippina. Emperor Claudius’s wife Messalina was put to death in the year 48 AD on charges of conspiracy. On January 1, 49, Agrippina married Claudius, making her his fourth wife. She also planned Nero’s marriage to his half-sister Octavia, which took place later in 53 AD. Claudius then formally adopted Nero on February 25, 50 AD, changing his name to “Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus.” Lucius was now called Nero. He was the legitimate successor to the kingdom since he was older than his adopted brother. Even though Nero was just 14 years old when Claudius freed him in 51 AD, he still went on to make Nero proconsul, invite him into the Senate, depict him on the coins.

Nero becomes Emperor

Claudius died of poisoning on October 13, 54 AD. In 54 AD, Nero’s reign as Emperor began when he was just 17 years old. From the start of his reign, he had the support of his mother, the scholar Seneca, and Sextus Afranius Burrus, prefect of the praetorium. He hoped to win over the common people and the military by offering bonuses. His personal life could be in tatters, but the Empire was in good hands. Nero was unhappy in his marriage and began keeping a former slave called Claudia Acte as his lover. However, Agrippina supported Octavia, while Seneca and Burrus backed the Emperor.

Nero prevented his mother from further meddling in his life by removing herself from the picture. He also faced constant competition from Britannicus, his adopted brother and a trusted ally of the majority. Britannicus, however, passed away unexpectedly on or around February 12, 55 AD. Suetonius and other ancient authors suggested that Nero might have poisoned him. It seems more plausible, however, that Britannicus experienced an epileptic fit before his death, which led to the burst of an aneurysm.

Nero lived a hedonistic life as Emperor and left state business to his counselors. In the year 59 AD, Nero had his mother, Agrippina, murdered, perhaps with the help of his beloved Poppaea. Despite Seneca’s best efforts, the Emperor’s reputation was damaged by this incident. From the year 62 AD on, further changes were done under Nero’s rule. Since Burrus had passed away, Nero needed a new advisor, and Seneca had already decided to step down.

Nero chose Tigellinus, who, upon taking office, issued a slew of anti-treason statutes. In addition, Nero’s mistress fell pregnant, and he still didn’t have any heirs. Everything got to the point where Nero wanted to marry her and end things with Octavia, so he did just that. Nero started by making false accusations of adultery against Octavia. Unlike Nero, though, Octavia was held up as an example of virtue. In the end, the divorce was finalized with Octavia’s infertility as the reason. On June 9, 62, Octavia committed suicide by cutting her veins, sparking widespread unrest.

Great Fire of Rome: Did Nero burn Rome?

The Great Fire of Rome occurred on July 18, 64 AD, near the Circus Maximus. Nero had taken a holiday to Antium at the time. As soon as he heard about it, he hurried back. The story spread like wildfire that Nero played lyre and sang atop the Quirinal as the city burned. In actuality, some historians believe that Nero welcomed the destitute inside his palace and fed them to prevent a famine. People blamed Nero since he was the one who announced ambitions to reconstruct Rome swiftly in a magnificent manner.

But Emperor Nero looked to the Christians as a new scapegoat for the populace. Starting in October, he launched a campaign of extraordinary persecution against them. Some he sent to the lions, while others he crucified and burned to death. The martyrdom of Sts. Peter and Paul is linked to these events in Christian mythology. But there’s no proof of it. Nero had a new palace constructed after the devastating fire, and it was much larger.

Nero the Olympic champion

Nero won the Olympic Games in 67 AD after spending around one million sesterces to bribe judges and organizers of the tournament. In the midst of his triumph, the Roman emperor makes the executive decision to provide tax exemptions to his Greek guests who are already residing inside Roman territory. Nero brought back 1,808 olive wreaths to Rome to celebrate every one of his “assumed” victories at the Olympics.

The death of Nero

Another controversy involved Nero in the year 65 AD. Since it was seen shameful for an emperor to engage in public entertainment, his reputation suffered. Pisonian conspiracy, in which his old friend Seneca played a part, was the next scandal. Roman statesman Gaius Calpurnius Piso intended to have Nero assassinated and Nero, in return, ordered Piso, the philosopher Seneca, Seneca’s nephew Lucan, and the satirist Petronius to commit suicide.

Nero also ordered a heroic general, who was well respected, to commit suicide as well. But Nero asked for too much without even realizing it. The military leaders were now planning a revolution against the Emperor. The historians Suetonius and Tacitus report that Nero had kicked his pregnant wife Poppea in the stomach which killed her. Nero then made another marriage proposal to Claudia Antonia, but she turned it down.

Consequently, Nero had her sentenced to death on the grounds that she was plotting against him. He wed his lover, Statilia Messalina, in May of 66 AD. Nero then spent a year traveling in Greece and treating himself to cultural performances while he was there. At the same time, in Rome, praetorian prefect Nymphidius Sabinus was trying to win over the support of the senators and the Praetorian Guard.

Nero had noticed a shift in the atmosphere since his return to Rome. Then the uprisings began. It started with Vindex, the governor of Lyon Gaul. Then the legate of the Legio III Augusta legion in Africa, which had been supplying Rome with wheat, stopped doing so. Later, Nymphidius Sabinus took over the Praetorian Guard (Imperial Guard). Nero was finally expelled from office by the Senate, and as a result, he took his own life. On June 9, 68 AD, at the age of 30, Emperor Nero slit his throat at the rural home of his loyal freedman Phaon, bringing an end to the Julio-Claudian Dynasty.

After Nero’s death, the Senate passed a resolution to damnatio memoriae Nero (condemnation of memory). Numerous civil wars and the change of imperial dynasties characterized the year 69 as the “Year of the Four Emperors.”

Family tree of Nero and his titles

Nero was the grandson of Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus and Antonia the Elder, daughter of Mark Antony and Octavia the Younger (the latter being the sister of Augustus and the grand-niece of Julius Caesar), adopted son of Claudius, son of Agrippa the Younger and also the great-great-grandson of former emperor Augustus (descended from his daughter Julia). From 53 to 62 AD, Nero was married to Claudia Octavia; from 62 to 65 AD, to Poppea, with whom he had a daughter who died shortly after birth; from 66 to 68 AD, to Statilia Messalina; and from 66 to 68 AD, to Sporus.

In 37 AD, Nero was known as Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; in 50 AD, he was known as Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus; and in 66 AD, he was known as Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus. Additionally, Nero held a number of magistracies and titles, including Pontifex maximus and Pater Patriae in 55 AD, consul in 55, 57, 58, 60, and 68 AD, and acclaimed Emperor in 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 66, and 67 AD. Nero also received the tribunician power (tribunicia potestas) in 54 AD, and had it renewed each year afterwards. His full title at the time of his death was “Emperor Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus Pontifex Maximus Tribunicia Potestate XIV, Emperor XII, Consul V, Pater Patriae.”

Legacy of Nero

The Emperor Nero is often seen in contemporary work. Henryk Sienkiewicz’s book “Quo Vadis?” which won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1905, is one such work; so, too, are Hubert Monteilhet’s “Neropolis.”

Several movies were born from Henryk Sienkiewicz’s work, including a 1951 film directed by Mervyn Leroy and starring Peter Ustinov as Nero. Brigitte Bardot plays Poppea in the 1956 film “Nero’s Weekend,” directed by Stefano Steno. Nero has appeared on stage (in Jean Racine’s “Britannicus”), in comics, and in video games. Operas including Claudio Monteverdi’s “L’incoronazione di Poppea” (1642), Anton Rubinstein’s “Nero” (1879), Arrigo Boito’s “Nerone” (1924), and Pietro Mascagni’s “Nero” (1935) were all inspired by him. Nero has even lent his name to a software for burning discs called “Nero Burning ROM.”

Key dates for Nero

- 15 December 37: Birth of Nero

Agrippina the Younger, Caligula’s sister, gave birth to Nero. That made him the Emperor’s nephew. Initially, he had no right to the throne. His mother, however, was well-known and influential, and she plotted for her son to one day become Emperor.

- 25 February 50: Claudius adopted Nero

Nero’s mother, Agrippina the Younger, was ultimately able to wed Emperor Claudius. Therefore, she also arranged for the Emperor to adopt him. Due to his seniority, Nero was anointed Emperor rather than Claudius’s younger son Britannicus.

- 13 October 54: Nero becomes Emperor

Nero became Emperor after the death of Claudius. Through the use of his authority, he had his mother murdered despite her role as an adviser at the start of his reign and he was later accused of killing his half-brother Britannicus, his chief contender for the throne. His rule was marked by brutality, an appreciation for the arts and a penchant for hedonism; he left official business in the hands of his entourage while he and his wife indulged in their passions. All of this would ultimately lead to his downfall and the end of his reign as Emperor.

- July 19, 64: Rome ravaged by a fire

The whole city of Rome was destroyed by a massive fire that started in the middle of the night near the “Circus Maximus.” It took six days to put out the fire because of its size. Having spent some time in the countryside, Emperor Nero hastened his return to the imperial city. He had a new palace constructed after the devastating blaze, and it was much larger. The commoners blamed him for starting the fire so that Rome could be rebuilt to his desires. The despotic ruler immediately pointed the finger at the Christian minority. Starting in October, he launched a campaign of extraordinary persecution against them.

- 9 June 68: Death of Nero

The reign of the Julio-Claudian Dynasty ended with Nero’s death. The Senate passed a resolution to “damnatio memoriae” him (condemnation of memory) when he passed away. Numerous civil wars and the changing of imperial dynasties characterized the year 69. It’s later called “The Year of the Four Emperors.”