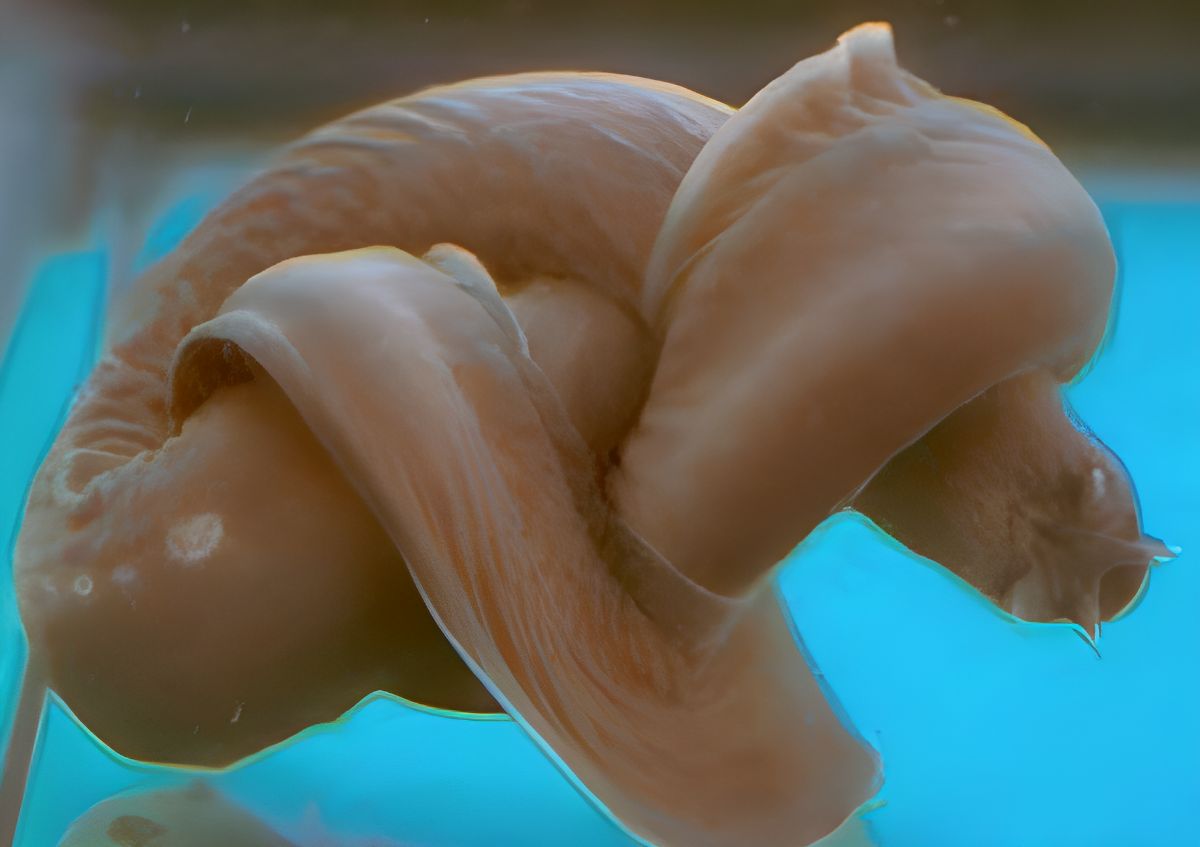

Researchers have unearthed the oldest known fossil of a snake that reproduced through live birth. Messelophis variatus fossils have been found in the Messel Pit, indicating that the species existed 47 million years ago. At the time of its demise, the boa was pregnant with at least two offspring, according to the fossil. Her children were placed in the back portion of her body and were already well grown.

The Messel Pit, located not far from Darmstadt, is often visited for its well-preserved snake fossils. Evidence that ancient snakes have infrared vision and the earliest known python have both been discovered there by paleontologists. There are still many unanswered questions about snake evolution.

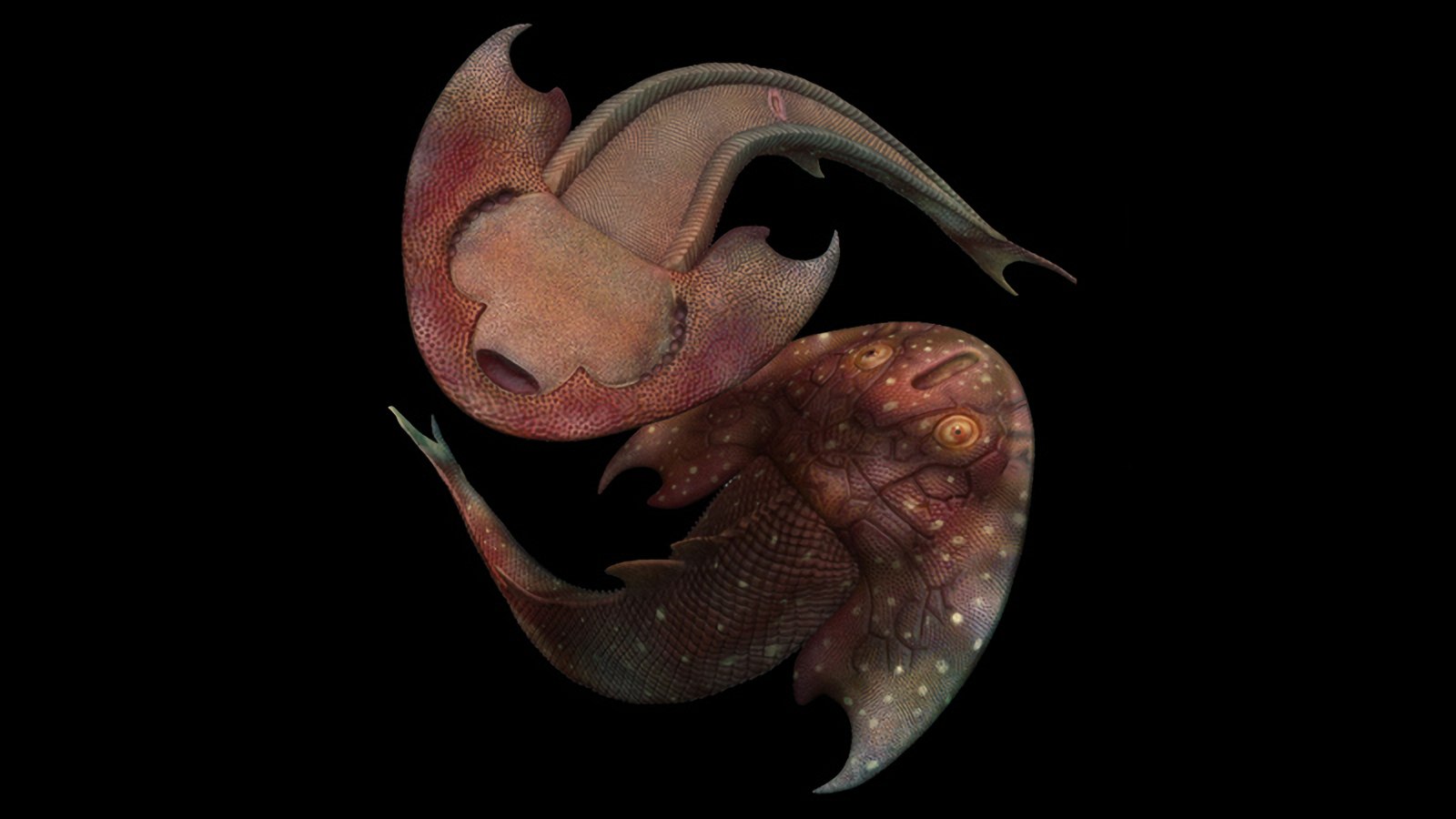

In the Messelboa Messelophis variatus, paleontologists have discovered the bones of at least two juveniles (shown by orange).

Time periods when snakes began delivering their young alive rather than from eggs are among these. Because many snake species use viviparity rather than egg-laying, despite the fact that this is the norm for most contemporary reptiles. They, like us, carry their young within until they are ready to be born, where they can develop safely. Up until today, it was unknown when snakes first began using this tactic.

Fossilized pregnant snake

The enigma is getting closer to being solved thanks to the efforts of a team headed by Mariana Chuliver of the Fundación de Historia Natural in Buenos Aires, Argentina. The pregnant boa fossil was found by paleontologists in Messel Pit sediments that are 47 million years old. This is the very first time a viviparous snake has been documented in the fossil record. According to the researchers, just two additional viviparous reptile fossil records have been found globally thus far, and none of them is a snake.

This new description concerns a Messelophis variatus boa that is around 50 centimeters in length and is one of the most frequent fossil snake species found in the Messel Pit. “We found that some of the skull bones in the fossil are from small boas no more than 20 centimeters long. These bones are located a good distance behind the stomach; if they were the snake’s prey, they would have already decomposed this far back in the gut and would not be recognizable,” said the coworker Agustín Scanferla. Too far advanced for oviparity, the snake was carrying at least two young.

Live birth despite the environment

The scientific team is baffled by the snake, however: Viviparity is used by modern reptiles almost exclusively in cold environments. The embryo is better shielded from the cold if the mother’s internal temperature is more stable than the ambient temperature. However, the Messelophis snake did not need to deal with frigid temperatures because of the environment in which it thrived. Typical temperatures in the Messel area were about 20 degrees Celsius, and it never got below freezing even in the dead of winter.

Although scientists cannot explain why the Messel pit boa gave birth to live young, scientists suggest that there may have been advantages for the young beyond shelter from the cold. Perhaps additional fossils from this particular location can help people answer this puzzle.