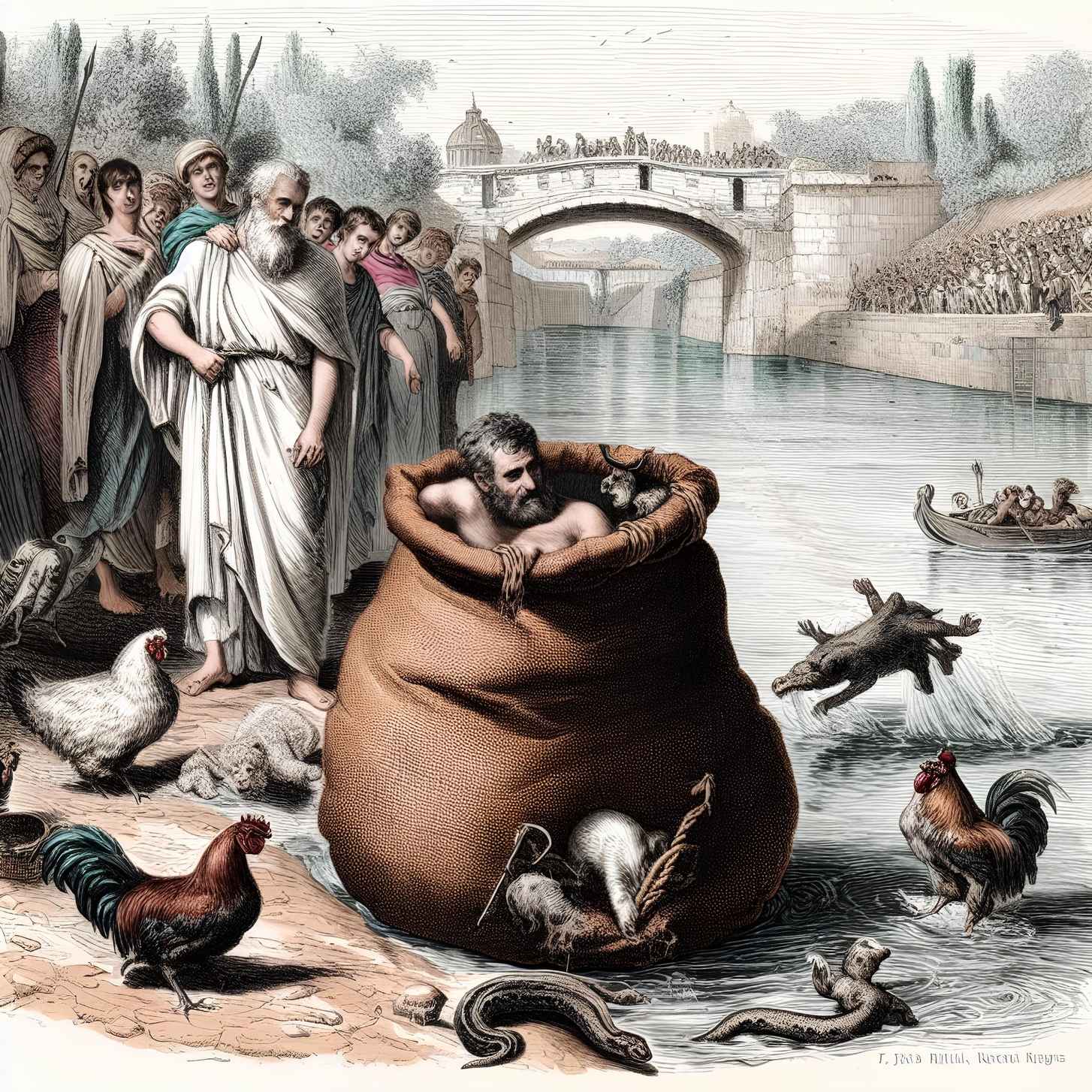

Poena Cullei: Sack Execution in Ancient Rome

In a Poena Cullei execution, the condemned person would be placed in a sack along with various animals like snakes, monkeys, and other creatures. The sack was then sealed, and the person, along with the animals, was thrown into a river or the sea.