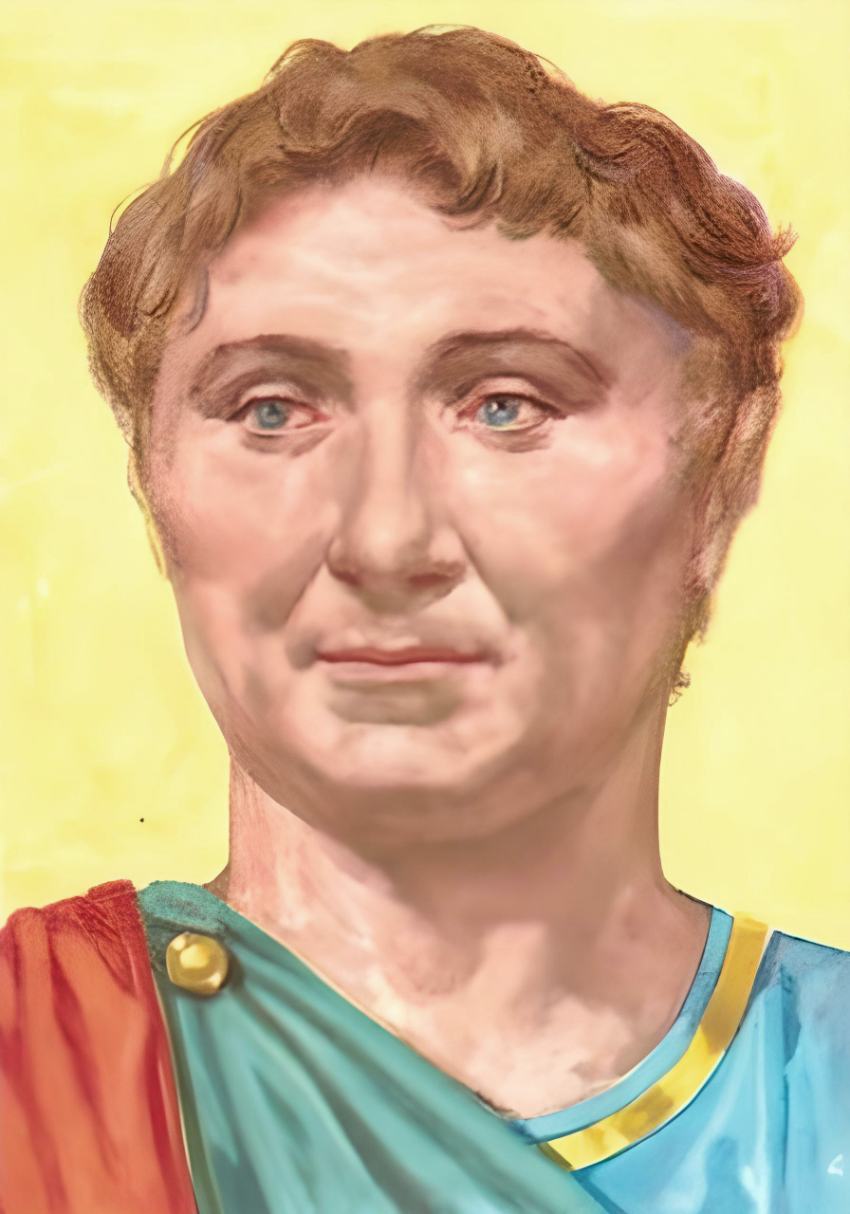

Pompey, a prominent Roman commander and politician, was born in the Italian city of Picenum on September 27, 106 BC. He was murdered at Pelusium in Egypt on September 28th, 48 BC. With Caesar and Crassus, Pompey created the First Triumvirate, although he was ultimately destroyed by Caesar at the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 BC. Pompey or Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus born into a wealthy plebeian family, earned the moniker “the Great” due to his outstanding military achievements. However, his competition with Caesar, previously allied, would ultimately be his undoing. Pompey was a well-respected Roman commander and politician. The Civil War that broke out in 49 BC would turn him into Julius Caesar‘s biggest antagonist, despite the fact that he was married to Caesar’s daughter Julia.

Pompey was a ruthless and brazen man, typical of the world’s elite. His innate or cultivated amiability, however, won the hearts of many.

Pompey’s early life

Pompey was born to a noble family and a demanding and harsh father. Pompey’s father was Cnaeus Pompeius Strabo, a substantial general in the Roman army. Pompeius Strabo stood out throughout the Social War (91-87 BC) because of his stubborn character. Thus, his funeral pyre was met with ridicule as the townsfolk despised him and burned his body.

Pompey followed his father and developed an interest in the military and strategic planning. His father’s wealth and extensive clients led Pompey to meet with Sulla. By that time, Sulla was in charge of the Optimates, the traditional political group that staunchly defended the privileges of the old nobility. While Gaius Marius, the head of the progressive Populares faction, had high hopes for the young Julius Caesar, nephew of his wife Julia, Pompey still remained a bright young guy in his eyes.

Since Pompey was trained for battle since he was young, it is only logical that he would first commit to a successful military career. Almost immediately, the politician Syula took notice of him, and he went on to battle in Africa and Sicily with successful campaigns in the Far East, Hispania, and against Mediterranean pirates.

Aeschylus’s blunt quote, “I hate the sire, but dearly love this child of his,” serves as the first line in Plutarch’s biography of Pompey the Great.

Pompey rose through the ranks of the Roman military and eventually became Emperor. With Caesar and Crassus, Pompey formed the triumvirate that ruled Rome beginning in 60 BC. Pompey married Caesar’s daughter, and the three of them ruled the whole Roman lands.

It was because of his efforts to bring back order in Rome that Pompey was named sole consul in 52 BC. But three years later, a civil war erupted, putting Pompey against Caesar. The latter was even designated an enemy of Rome by that time. After being soundly beaten by Caesar in Greece in the legendary Battle of Pharsalus, Pompey was assassinated on an Egyptian beach.

After the Pharsalus, Pompey had sought refuge with Ptolemy, King of Egypt, but Ptolemy ultimately betrayed him, killed him and gave his head to Caesar. Pompey was a military hero who also founded towns like Nicopolis and Pompeiopolis. He also created the Theatre of Pompey in Rome.

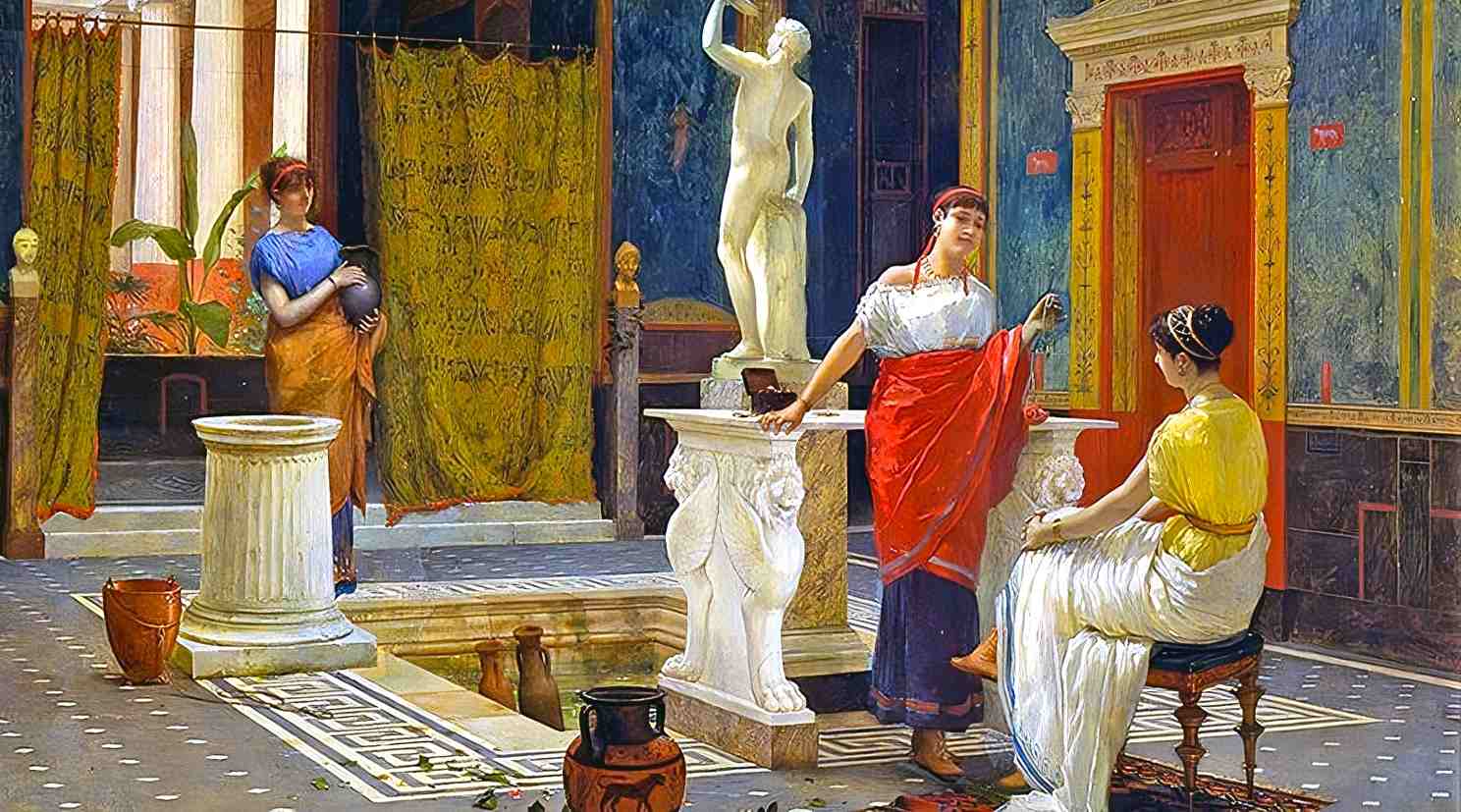

Rome during Pompey

The political systems of the city-state of Rome were in need of a revival because of the decline of the Republic in comparison to the vast geography of the Empire. The collapse of this political system paved the way for constant civil wars and provided the ideal environment for the power grabs of the ambitious. Pompey was a ruthless and brazen man, typical of the world’s elite. His innate or cultivated amiability, however, won him many friends and admirers. And he was looking good, too. His demeanor was courteous, and his eyes were a mix of softness and fervor. Pompey was quite popular with the ladies, and the stunningly beautiful famous courtesan Flora was completely smitten with him.

These deadly good looks were complemented by a rebellious strand of hair that was lifted by a spike on the forehead, giving him phony Alexander airs. After the successful campaigns he commanded in Africa in 81 BC against Marius’s supporters, his warriors took to calling him “Magnus” (Great) in honor of this trait and his military prowess in reference to Alexander the Great. This distinction was one that Pompey gladly accepted, revealing much about his aspirations.

Insolence that portends disaster

Despite the norms, Pompey still planned to ride a tank hauled by African elephants around Rome during the celebration of his victory. He was more of a strategist than a scenographer, and thus he failed to foresee that his excessively imposing chariot would prevent him from entering the city. Being ridiculed might be fatal in ancient Rome, but not to a man of his type.

In 79 BC, Pompey was just 26 years old. Despite being a member of the equestrian order (the lower Roman nobility), Pompey was so confident in his triumphs that he petitioned the Senate for the magistracy of consul, an honor normally reserved for the senatorial class. His teacher Sulla (who served as dictator in 82–79 BC) thought this request was a sign of arrogance and bad luck, so he decided to distance himself from Pompey.

When it became clear that Pompey would no longer have the backing of the optimates’ leader, he moved to support the election of Sulla’s opponent, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. For Sulla, Aemilius Lepidus was a filthy provoker. However, this coincidental union did not survive for very long. Aemilius Lepidus revolted against the Senate and in return, Pompey suppressed this rebellion with an army raised from Picenum. After defeating Aemilius Lepidus on the battlefield, Pompey removed him from power the next year.

A path to victory

When the Spartacus revolt broke out in the city of Capua, Pompey arrested 6,000 rebels and had them crucified one every 108 feet (33 meters) along the route leading from Rome to Capua. The commander hoped to send a message to the slaves to discourage them from trying to escape.

Pompey resumed his Hispanic campaign in 77 BC. His new mission was to put down the rebellion led by another Marius admirer. Following a string of close engagements, General Pompey finally delivered a decisive defeat to Sertorius. He put up a monument to himself atop Col du Perthus (Perthus Pass) as a last act of egotism before departing the Iberian Peninsula. According to his inscription, Pompey had conquered 87 cities. Surely he totaled even the tiniest villages along his route.

Even though the Romans had been humbled by revolts for months, but the victor of Sertorius had not yet departed Spain. While trying to flee, Spartacus and his band of 100,000 slaves completely routed the army. Even a seasoned general like Crassus had run into trouble. In 73 BC, he received assistance from Pompey and Lucullus. Most of the rebels were eliminated by their forces. Capturing 6,000, Pompey then had one crucified every 108 feet (33 meters) along the route from Rome to Capua, where the uprising had begun.

The commander hoped to send a message to the slaves that would discourage them from trying to escape. In Rome, people did not question the authority of rulers. So, it was another one of Pompey’s clever “stunts” when he publicly earned credit for putting down the Spartacus rebellion.

Pompey’s hopes for absolute power were now bolstered by this fresh triumph, and he quickly took advantage of the admiration to which he was subject in Rome to make another consulate submission while failing to fulfill the requisite conditions once again. But the senate had to make an exception for Pompey because of how popular he was, and therefore, Pompey and Crassus were both chosen Roman consuls (prime ministers) in 70 BC.

Despite their election, the two men first hesitated to dismiss their troops which created fear of a new civil war. But, too much blood had already been spilled, and so the two consuls decided to simultaneously demobilize their legionaries. But this did not signify a permanent abandonment of their goals, rather, it was only a temporary pause.

Pompey’s wars against the pirates and Mithridates

Pompey used his naval prowess to once again make a name for himself in 67 BC. The Gabinian Law granted Pompey extraordinary authority, the imperium. He was therefore endowed with the authority to completely wipe out the Mediterranean’s piracy problem. Their attacks hampered commerce and threatened Italy’s food supply, as much of their wheat originated in Egypt. With his fleet of 200 vessels, Pompey was able to effectively eliminate the pirate threat and square up the maritime space in just three months. Now a hero in the eyes of the Athenians, Pompey then established some of the reformed pirates in Soli, in modern-day Turkey. He planned to turn those pirates into farmers by placing them far from the sea. But the city of Soli was destroyed by Mithridates, and yet there was a request for revival by its inhabitants. So, Pompey rebuilt the city and named it “Pompeiopolis.”

The lawmaker Gaius Manilius then gave Pompey the chance to steer the war against the king of Pontus, Mithridates VI Eupator, a few months after this victory. Mithridates’ reign of terror in the East was a direct result of his refusal to abide by the terms of his treaty with Rome. Pompey was given free rein to eradicate this threat from the East and restore peace to the area.

He defeated King Mithridates’ soldiers with a daring nighttime assault in the Battle of the Lycus in 66 BC. In the East, Pompey kept pushing forward. Some, like Armenia’s King Tigran, chose to work with Pompey rather than oppose him. However, many other kinglets met their end because they were too egotistical to take the diplomatic route. The ever-victorious General Pompey brought the East to its knees and annexed the territories of Pontus and Bithynia on the southwestern bank of the Black Sea. Pompey even managed to put the King of Parthia, Phraates III, in a bind.

General who strikes fear in his subjects

However, Pompey’s progression did not end there. The Judean rulers came to him to put an end to a power conflict in 63 BC. Pompey saw his chance to crush Judea and took it for his own. On a Saturday, he led his legion into Jerusalem. Since that was a holy day, the Jewish army chose to refrain from battle. Approximately 13,000 of them were slaughtered in the temple where they took refuge. Judea was now dependent on Rome, and its new king, Hyrcanus II, was revered by Pompey and treated like a subject by the Romans.

Pompey thought about going home to Italy to revel in his victory. While returning, he followed in Alexander’s footsteps by establishing new towns as monuments to his greatness. After arriving at the city of Brindisi, he dispersed his forces to show the worried and admiring senate that he would not seize power via force. Pompey gambled on marriage ties as a means of gaining sway at the highest levels of politics. By allying himself closely with the more traditionalist Optimates, Pompey hoped to emerge as their new champion. As a result, he set his sights on tying the knot with a member of the Cato family. But the seasoned Stoic refused to give Pompey his niece in marriage.

Pompey finally realized what was going on here. His frequent victories and his will to succeed were worrying his would-be friends. He had already towered above many others and appeared menacing. Thus, he decided to look for a man who would understand him better. Similarly, Caesar also made his subjects fear him with reverence and respect. The two men agreed that it was time to join forces against the rest of Rome. In 59 BC, Pompey married his new friend Caesar’s daughter, Julia, to solidify his alliance.

In their agreement to aid each other’s rise to power, Caesar and Pompey invited Crassus to this secret pact. The First Triumvirate planned to get Pompey and Crassus elected consuls and then vote to give Caesar more time in Gaul. Everything went according to plan. However, the pact was altered following Julia’s death in 54 BC and Crassus’ death in 53 BC in the East, two years after his consulship.

Caesar vs. Pompey: a showdown between giants

As early as 51 BC, Caesar ruled all of Gaul. Getting back to Rome and taking up a new consular position was high on Caesar’s list of priorities. The two men were destined to clash, at least in Pompey’s opinion. As a strategic move, Caesar suggested that his army be disbanded if Pompey would do the same. That was the equivalent of signing a symbolic nonaggression pact. But Pompey refused and instead called Caesar, who had recently defeated the chieftain of Gaul, Vercingetorix, to return to Rome after dismissing his men.

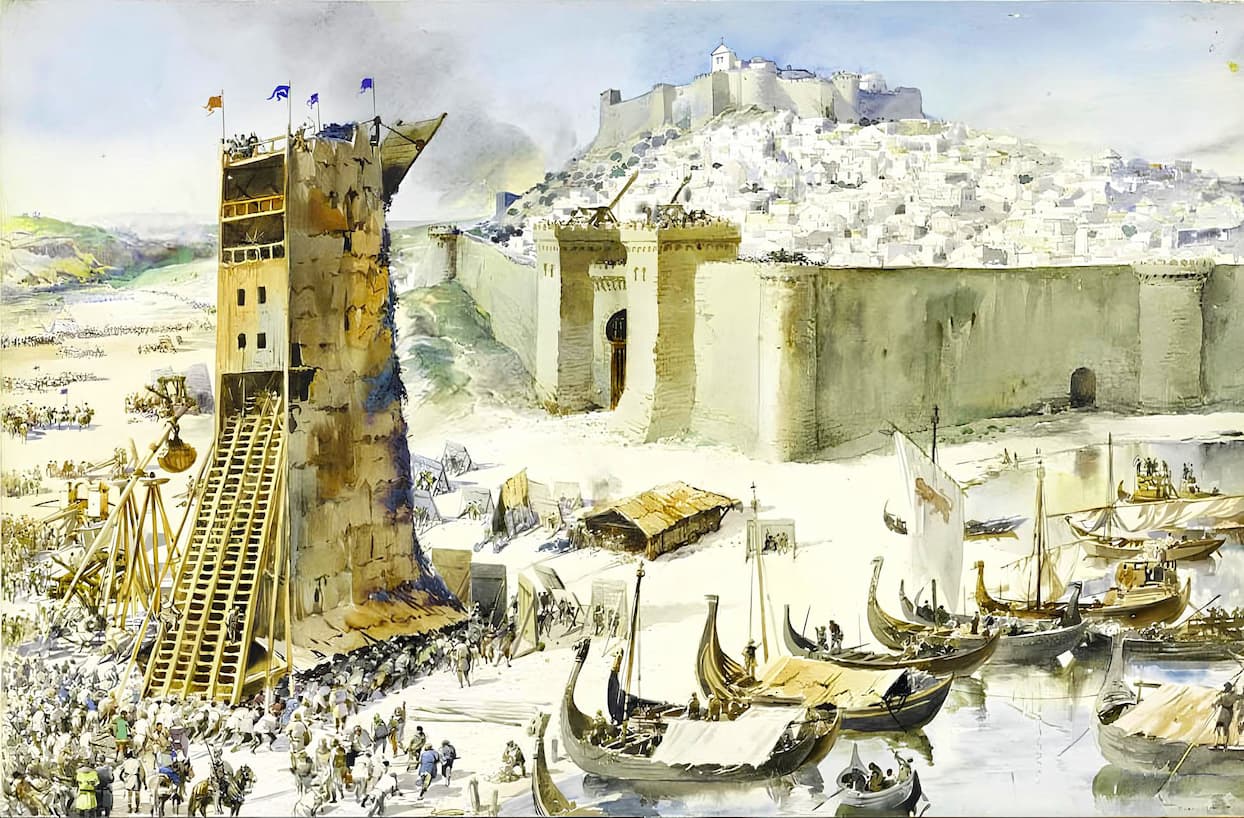

But Caesar led his soldiers to cross the Rubicon River on January 12, 49 BC. The warning was crystal clear: The time for a titanic clash was drawing near. If there was to be a conflict, Pompey knew it would be in the city of Rome, which would not end well for him. Caesar’s army, bolstered by their Gallic successes, marched toward Pompey, while Pompey’s forces were outnumbered. It was on March 19 that Pompey departed Rome for the East, where he intended to reorganize his forces and force Caesar to meet him on neutral ground.

The two generals fought a sort of positional battle in the spring of 48 BC, near Dyrrachium in Albania. Because of supply shortages, their soldiers had to endure. But both knew that it would be risky to go on the offensive under the circumstances. Nonetheless, on July 10, both armies clashed in the Battle of Dyrrhachium which took place from April to late July and ended in a non-trivial defeat for Caesar’s army.

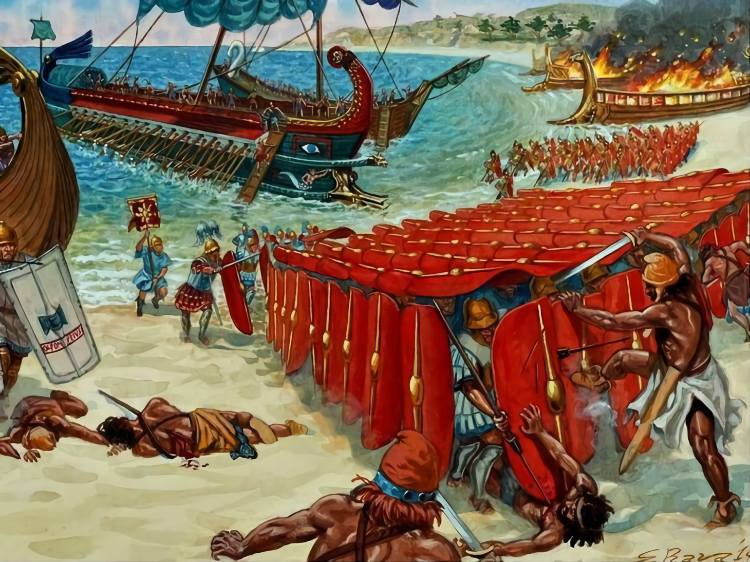

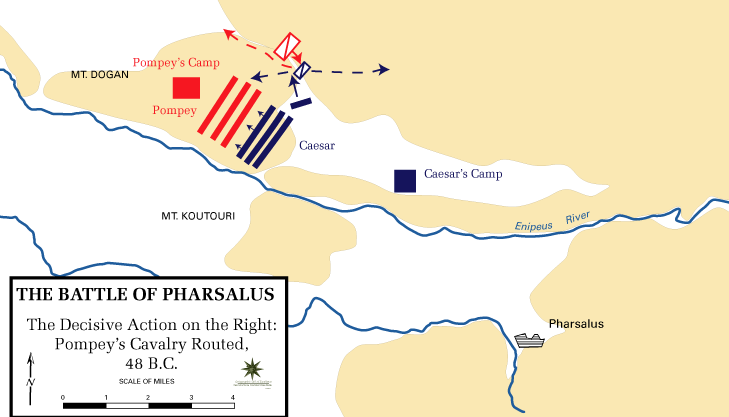

But on August 9, 48 BC, near Pharsalus in central Greece, the two armies met again at the Battle of Pharsalus. Pompey lost 6,000 troops and another 24,000 captured, while Caesar only lost 1,200 men. Pompey admitted that this overwhelming defeat was the worst of his life. He escaped the camp and his soldiers while disguised as a regular civilian.

On August 9th, at Pharsalia, Pompey stated he had just faced the worst defeat of his career. 6,000 of his soldiers lay dead, while another 24,000 were captive. As for Caesar, he had only lost 1,200.

Pompey approached Ptolemy XIII, Cleopatra’s brother-husband, in a mad attempt to get revenge. He believed that hiding out in Egypt would buy him enough time to face his father-in-law, Caesar, again. On September 28th, his ship anchored off the coast of Pelusium, in the northern Nile Delta. A small group including the young pharaoh’s advisors greeted Pompey when he arrived aboard a boat. One of Pompey’s former centurions, the Roman Lucius Septimius, had been stationed in the Nile Valley for some time. While Pompey was caught off guard and trapped in the boat with no way to escape, the former legionary dealt the killing blow. Ptolemy XIII’s advisors, Pothinus and Achillas, had joined him in the assassination of Pompey as they watched Pompey die helplessly on the ship.

Pompey had a fantastic career and deserved more than such a death. His body was cast onto the shore, pouring boiling blood, and his head was severed by Achillas. Ptolemy XIII believed he held a priceless treasure in his hands: the head of one of Rome’s best tacticians. The killers fancied themselves more cunning than Pompey and hoped that by pleasing Caesar, they might secure his support. But rather than causing an ensuing peace, the death of Pompey sparked a civil war. Caesar still had the utmost respect for Pompey. He admired Pompey’s drive and professionalism in the military. He had, no doubt, enjoyed the confrontation and was honored to see such a skilled tactician struggling. Caesar and Pompey were mirror images of one another, and thus, Pompey went down in history as Caesar’s only truly legitimate competitor.

Key dates in the history of Pompey

60 BC: The First Triumvirate

In order to become Consul of Rome, Julius Caesar created a covert alliance with Pompey and Crassus, which they called the First Triumvirate.

59 BC: Caesar, Consul of Rome

A triumvirate consisting of Pompey and Crassus and Julius Caesar allowed the latter to assume the position of Consul.

149 BC: Julius Caesar crosses the Rubicon

In order to unite Cisalpine Gaul and Italy, Julius Caesar led the 13th Legion over the Rubicon River. However, without permission from the Roman Senate, no military commander could cross this frontier.

Julius Caesar broke Roman law and declared war on the Senate by disregarding this edict. While crossing the Rubicon, he yelled “Alea iacta est,” which means “The die is cast,” in popular Latin. Nothing could stop Julius Caesar from entering Rome, removing Pompey, and eventually becoming dictator for life over the whole Roman Empire.

August 9, 48 BC: Pompey defeated by Caesar

At Pharsalia in Thessaly, Caesar pursued and decimated Pompey’s forces. Following Caesar’s crossing of the Rubicon (the river dividing Gaul from Italy), Pompey and the Senators fled Rome and headed for Greece a year earlier. After Caesar’s defeat of Pompey, the latter sought asylum in Egypt with Ptolemy XIII, but Ptolemy XIII had him murdered because he was afraid of retaliation from Caesar.

September 30, 48 BC: Assassination of Pompey

Ptolemy XIII, Cleopatra’s husband, had the Roman commander Pompey, Caesar’s adversary, killed. The Egyptian pharaoh planned this assassination in an attempt to win Caesar’s favor. But it was unlikely that the Roman Emperor would appreciate this favor. In the end, Caesar had the pharaoh deposed so that Cleopatra could rise to the throne, and then he became her lover.

47 BC: Julius Caesar meets Cleopatra

As Caesar tracked down Pompey in Egypt, Julius Caesar found out that he had been murdered. He became resentful of Ptolemy XIII, the pharaoh, who was at odds with his sister-wife Cleopatra. The Egyptian Queen had an instant and profound effect on the Roman commander. Following his successful military campaign against the monarch, Caesar handed over Egypt’s throne to Cleopatra. They were now expecting a boy.

March 15, 44 BC: Assassination of Julius Caesar

Despite being named dictator for life, Julius Caesar was killed. 50 Senators, all of whom supported the reinstatement of the oligarchic republic, piled on top of Caesar during a session of the Senate and delivered 23 sword blows. Caesar died next to a monument honoring his opponent, Pompey. Caesar had a lot of respect for Brutus, the son of his mistress, and he had a lot of respect for Cassius, a Roman commander, who were both involved in the assassination.

Bibliography

- “Parallel Lives, The Life of Pompey,” 2nd century AD, by Plutarch.

- “The Mithridatic Wars”, by Appian.

- “Pompey the Great,” 1978, by John Leach.

- “The Civil War,” by Julius Caesar.

- “Commentarii de Bello Gallico,” by Julius Caesar.