Has the Sahara always been a big desert?

There was a time when the Sahara was much bigger than it is now. When the previous ice age ended, it was characterized in the temperate latitudes by the demise of mammoths and other great herbivores. However, in Africa, this was mirrored by an increase in rainfall and the development of arable land. It was during this wet era that the Sahara finally began to bloom, with once-rare oasis becoming lush valleys, broad, full-flowing rivers winding through them, and the biggest lake in Central Africa, Chad, growing to over eight times its current size in just a few millennia.

- Has the Sahara always been a big desert?

- How long have Africans been eating bananas?

- Were there no states in tropical Africa before the first Europeans arrived?

- How many slaves were taken from Africa?

- How many peoples and languages are there in Africa?

- What is the mystery of the “clicking” language of the Bushmen?

- What do Africans believe?

- Africa has always been famous for its witchcraft. How widespread is it on the continent today?

- Is it true that Africa is filled with many diseases unknown to science?

Thanks to these factors, the Sahara Desert was swiftly populated by Neolithic Africans. In the Fertile Crescent, which covers eastern Asia and the Nile Valley, people figured out how to produce the first crops (wheat, barley, and millet) and domesticate cattle some 7,000 to 9,000 years ago, and word swiftly traveled across Africa north of the equator.

After then, the Sahara started to dry up and transform back into a desert. Yet, there is a silver lining to every cloud, since it was through this migration to the Nile Valley that the world’s first civilization arose: ancient Egypt.

How long have Africans been eating bananas?

The myth that Africans have always subsisted solely on the bounty of fallen bananas and mangoes from the heavens is a gross generalization. Mangoes and bananas are two of the most popular fruits in the world, yet they were just recently brought to Africa. The inhabitants of the Indonesian islands brought many fruits with them, including bananas. However, Africans have developed their own crops, such as the yam (still a staple meal in West Africa), wild rice (not the same as in Asia, but still extremely good), millet, and oil palm. Another type of wild ungulate, the forebears of today’s long-horned cows of the African savannah, were almost certainly domesticated there as well.

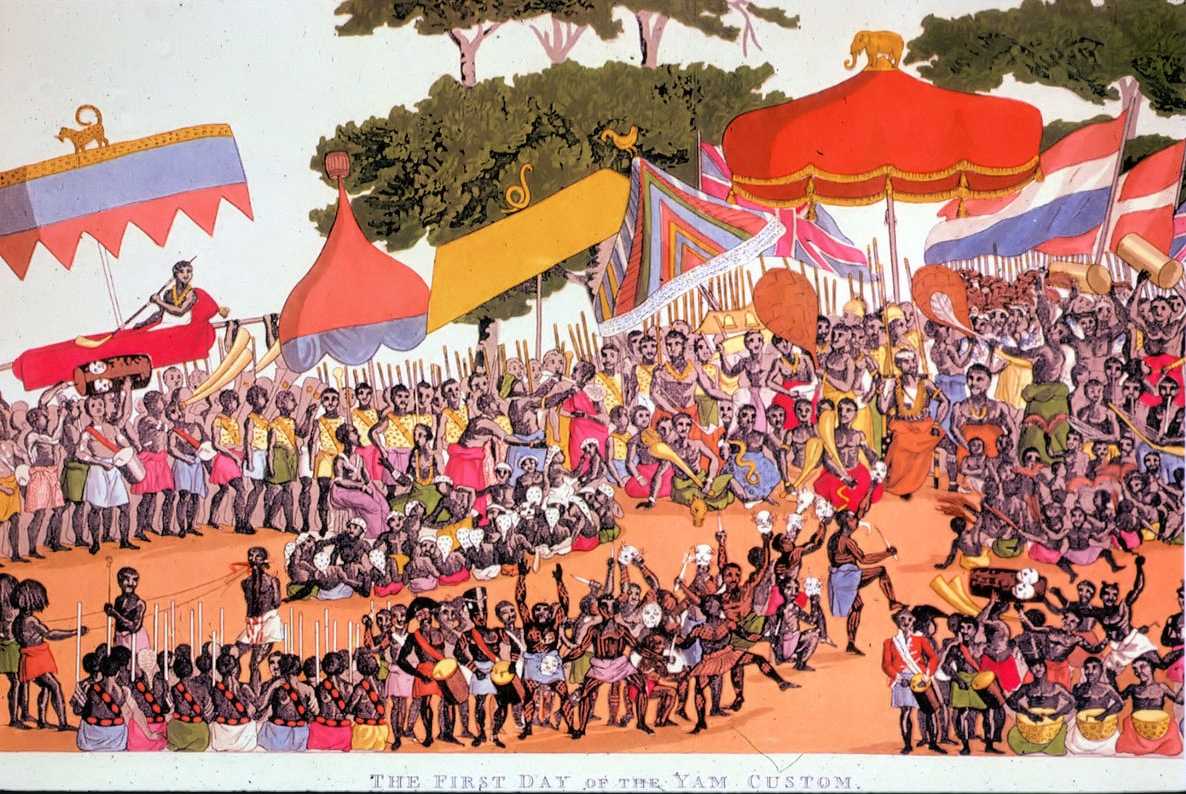

Were there no states in tropical Africa before the first Europeans arrived?

The first Europeans were the only ones who held this view. Scientists, explorers, and missionaries who saw the massive Great Zimbabwe ruins in southern Africa in 1871 concluded that the site could not have been constructed by Africans. European geographers concluded that the ancient Egyptians, Romans, Phoenicians, and Arabs must have constructed this enormous stone metropolis, while the Greeks’ acropolis and the ruins of King Solomon’s “mines” were identified as the granite tower and oval temple, respectively. Great Zimbabwe was the seat of the great state of South Africa, founded by the Shona people between the 12th and 14th centuries; nevertheless, it wasn’t until later that historians, archaeologists, and ethnographers were able to verify this.

Western Africa has been home to powerful states dating back to antiquity, some of which even outranked their European counterparts. When describing Ghana, Arab visitors said things like, “Gold grows there like carrots and is picked before morning.” Or the Mali Empire, whose monarch Kankan Musa made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 and brought back no less than 13 tons of gold to give to the people of the towns in the Middle East. Gold prices in Egypt and the Middle East plummeted after his visit and remained low for the next decade. The Songai Empire, the biggest in West Africa, was a little bigger than Western Europe.

The East African region witnessed the rise to glory of Ethiopia and the richness of Zanzibar and Kilwa. Congo and Monomotapa, two states in the south, saw great success. Forty independent African nations existed by the time Europeans began to divide the continent in 1870, which is almost the same number of independent African states that exist now.

How many slaves were taken from Africa?

Between the 16th and 19th centuries, it is estimated that 10–12 million individuals were sold into slavery from West, South, and East Africa. Since at least 10–15% of slaves perished on the ocean voyage, it is highly doubtful that accurate counts would ever be determined. However, the unfortunates were not just sent to plantations in the United States. The lengthy practice of slave trade in the Indian Ocean was given a boost in the 15th and 18th centuries when more and more people were shipped as slaves from the eastern coast of Africa to the Middle East and South Asia. The Kanem-Bornu empire along the banks of Lake Chad also continued to transport slaves over the Sahara to Egypt and the Middle East in return for armaments. Exports accounted for nearly 90% of the eunuchs valued at the courts of Middle Eastern sultans and emirs. In the Middle East, a skilled eunuch was worth 10 times as much as the most beautiful slaves.

It was the obligation of both the vendor and the customer to prevent human trafficking. Slaves were seldom taken by European forces; instead, they were offered for sale by the leaders of coastal princes and tribes, who knew full well that by selling their people into slavery, they were condemning them to a life of servitude or death. How many of them experienced guilt over their actions is unknown to us. The purchase and resale of slaves were not illegal in Africa. This practice dated back thousands of years, and it was only abolished when England and France banned drug trafficking and possession in the middle of the 19th century, followed by the United States. Slavery was finally abolished in the last country to remain independent from European influence, Ethiopia. It wasn’t until 1942 that slavery was finally abolished in that country. Domestic slavery, however, persists even today in areas of the continent where central authority is still weak.

How many peoples and languages are there in Africa?

Even though 2,000 distinct languages have been identified on the continent, the border between language and dialect is sometimes highly fuzzy, and many of these languages are still poorly understood. Some nations, such as the relatively small nation of Cameroon, are home to individuals who speak several hundred different languages, although a given language is often spoken in no more than five or six villages. There are probably twice as many individuals (or ethnic groupings, to be more precise) in Africa. Therefore, it is not surprising that most Africans are multilingual from an early age, speaking not only their native tongue but also two or three neighboring tongues, the prestige tongue of the entire region, and the colonial language (typically English, French, or Portuguese) in which most education and media are provided.

However, scientists believe that all of this linguistic diversity stems from just four great ancestral languages and can be categorized into four large families: the Afrasian family (spoken primarily in North and East Africa), the Niger-Congo family (spoken primarily in West and South Africa), the Nilo-Saharan family (spoken primarily in East and Central Africa), and the Khoisan family (the most mysterious of all languages).

What is the mystery of the “clicking” language of the Bushmen?

The Khoisan are Africa’s smallest (only 30 languages) but the most unusual linguistic community, whose languages are spoken by Hottentot cattlemen in the continent’s south (who call themselves Khoi) and semi-nomadic hunters and gatherers known as Bushmen (San). In terms of both language and linguistic history, the Khoisan are one of Africa’s most intriguing mysteries. Geneticists have found that the structure of the Khoisan genome is very different from that of any other human on Earth. This may suggest that the Bushmen and Hottentots’ ancestors were the first to break away from the human family tree.

“Click” consonants are a trademark of Khoisan languages. These noises can’t be compared to anything else out there. The tongue clicks “tsk-tsk-tsk” that we heard from grandma as a rebuke for eating jam ahead of time or the click of the tongue against the back teeth with which a horseman drives his gloomy steed are not sounds that we consider to be part of the English language and are not used in words. These and similar clicks (as they are known in linguistics) made with the lips, tongue, palate, and teeth can combine to create words and are used more frequently than standard consonants in Koysan languages. There are several types of clicks: lip clicks (which sound like a dry kiss), tooth clicks (which sound like your granny but clearly mean “don’t mess around”), palatal clicks (in which the back of the tongue touches the palate), alveolar clicks (in which the tip of the tongue touches the alveoli above the upper teeth), and lateral clicks (the tongue, back teeth, and cheek are involved; this is the jockeying sound). In most Khoisan languages, these five clicks are linked by an articulation that includes the vocal chords, and the number of these articulations (or “exits”) can occasionally approach two dozen. There are at least 70 click sounds used in the K’khong Bushman language.

Several theories have been put forth to explain where clicks first appeared. These phonemes almost certainly featured prominently in the language of prehistoric people but have now been lost in every region of the world save Africa. The Khoisan languages have an unusual collection of vowels, which is almost as unexpected as the click sound. Some researchers have determined that there are 88 vowel sounds in the Khong language. They might be lengthy, short, nasal, or articulated posteriorly and laryngeally. The so-called “whispered vowels” are a specific set of vowels that may be said with far less effort than usual. Linguists are at a loss to explain why a smaller set of vowel sounds is essential to the proper functioning of language and what purpose the vast array of vowel sounds serves. Perhaps these enigmas stem from the fact that the Khoisan language is so ancient, with some experts believing it to be a relic of humanity’s earliest spoken language.

What do Africans believe?

Though Christians and Muslims now make up almost an equal share of Africa’s population, neither religion has ever abandoned its historic practices. It is not common for people in tropical Africa to have strong allegiance to a single religious tradition, and they are not used to the kind of authoritarian religious doctrine that is popular in Europe and the Middle East. Even after legally adopting the new faith, the monarchs of Islamic republics in Africa continued to partake in ancient festivities and were not hesitant about eating during the holy month of Ramadan, as was harshly observed even in medieval Arab chronicles.

They saw no need in praying five times a day and wondered why they should have only four wives when they might have as many as 144. Ibn Battuta, a Muslim traveler who lived in the 14th century, was outraged to see that the daughters of African Muslim lords danced in the streets of the city while completely unclothed. The peasants, on the whole, continued to follow the religion of their ancestors, and even if they went to a mosque, they did not hurry to abandon their former beliefs.

It is still possible for Christian and Muslim believers to cohabit peacefully with those who honor their ancestors, the spirits of the land (stones, trees, groves, rivers, and lakes), and holy totem animals. Among Africans, there is a widespread belief that Christ will grant wishes for free, but not soon, while the native Zangbeto spirit is more rapid but expects too much in return. Traditional priests in Ghana often employ the Bible with pounded monkey skulls, amulets, and incense during rituals. They may even bring the Koran for added insurance.

A contemporary understanding of faith and religion draws clear distinctions. As a result, a person can believe in God, a black cat, horoscopes, and esoteric living knowledge without ever setting foot inside a church or knowing a single Orthodox festival (other than Easter). Most of us no longer think of lightning as a heavenly hand, and only the most desperate fanatics still believe in incantations, hexes, and dream books; thus, the range of supernatural powers is shrinking.

In African cultures, norms and expectations are different. The African mind does not automatically categorize events into the normal and the supernatural. According to him, there is only one planet, and all gods, spirits, humans, and animals live inside it. While it’s true that some of the creatures there aren’t readily apparent, as one Ugandan put it, “A bedbug is invisible too, but no one would consider talking about its supernaturalness.” Especially, he added after much reflection, spirits can appear to a person in any guise if they want to, but bedbugs never do.

Africa has always been famous for its witchcraft. How widespread is it on the continent today?

Today, in Africa, the blame for almost every tragedy is first put on witchcraft, whether it be the fate of an individual, a household, a community, a city, or even a country. There is only one explanation for the annihilation of livestock, the failure of rain clouds to materialize, the sudden passing of a newborn child, and the loss of a harvest of grain at the hands of birds because the watchman fell asleep at his post: someone from the world of ill-wishers has used black magic against the locals. Surprisingly, this straightforward analysis aids in not just comprehension but also the conquering of adversity. A sick guy is just someone who had an evil obsession injected into his body by a sorcerer who swooped into his house on the wings of a bat at night. Unless the healer (the same sorcerer, but much nicer) can reach him, he will die soon. The healer, on the other hand, is usually successful: after several rites and manipulations of the ill person’s body, he deftly suckers a bundle of grass, bird feathers, or stones out of the sorcerer’s victim.

People who believe they are afflicted with a witchcraft spell generally succumb to their fears and die, making this therapy one with profound psychological potential: following the “healing” operation, the patient will undoubtedly believe that they are better. If the illness kills him, his family will know that “the witchcraft spells were too strong; it was necessary to pay the healer extra money.”

No era, not even the modern one, is equipped to handle witches. Many nations have passed laws against witchcraft; in the Seychelles, grigri witches are considered criminals and are actively sought by authorities. Governments in several African countries set up specialized “witch camps” where people who have been accused of witchcraft or exiled from their communities can be held until they are deemed harmless. Witches are often found among the crippled, lame, and deaf; they will almost inevitably be considered albinos. In many regions of Africa, twin children are viewed as portents of doom for their communities, spreading the prevailing witchcraft fear throughout the region.

In other situations, an African may grow to believe he is a sorcerer or witch as a result of the anti-sorcery mania in which he is continually immersed. The spells will be broken, and the witch from yesterday will consider herself cured forevermore when a certain ceremony has been performed on him.

Is it true that Africa is filled with many diseases unknown to science?

Once overshadowed by Ebola, Africa’s other major health problems—malaria, yellow fever, typhoid, sleeping sickness (trypanosomiasis), amebiasis, schistosomiasis, and, of course, AIDS—remain serious problems. Vaccines provide protection against a wide range of diseases, including potentially fatal typhoid and yellow fever. However, malaria is one disease for which there is currently no vaccine. Malaria has been there for thousands of years in tropical Africa, and it is responsible for 1.5–3 million deaths annually, which is 15 times more than AIDS and 500 times more than Ebola. Approximately every 30 seconds, a kid in Africa dies from malaria, according to some estimates. Thousands of European settlers died from malaria before the discovery of quinine in the late 19th century.

The tsetse fly, which all African kids know and fear, is the vector for trypanosomiasis, often known as sleeping sickness. Despite popular belief, tsetse mostly feeds on cows and is responsible for the most devastating epidemics experienced by Savannah’s cattle farmers. However, its bite is terrifying to people as well. Trypanosomiasis can be fatal if left untreated, but contemporary medicine offers effective treatments that can eradicate the illness at nearly any stage. As an added bonus, the tsetse fly may be readily warded off by using either a repellant or simply by donning a white, baggy outfit.

Amebiasis, also known as amoebic dysentery, is a well-known African illness. The dysentery ameba, the disease’s causal agent, is found in raw water and is simple to ingest. Therefore, it is important for people in Africa to exercise caution while consuming water. If feasible, they should only consume water that has been bottled and sealed by a factory or that has been heated. This process gives water an unpleasant aftertaste, but it ultimately protects human health. Antimicrobial drugs have greatly improved people’s ability to deal with the illness.

HIV, also known as simian immunodeficiency virus, or SIV, is a virus that was first transmitted to humans from monkeys in the Congo in the late 19th or early 20th century. Twenty-seven percent of the world’s HIV patients are located in countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The epidemic has thankfully peaked, and the number of new HIV infections is falling. It is still present in up to 26% of the population in Swaziland, 23% of the population in Botswana, and 17% of the population in South Africa.

Sources:

- Collins R., Burns J. A History of Sub-Saharan Africa. 2007.

- Tucker Childs G. An Introduction to African Languages. 2003.

- Gamal Mokhtar. General history of Africa, II: Ancient civilizations of Africa. 1981.