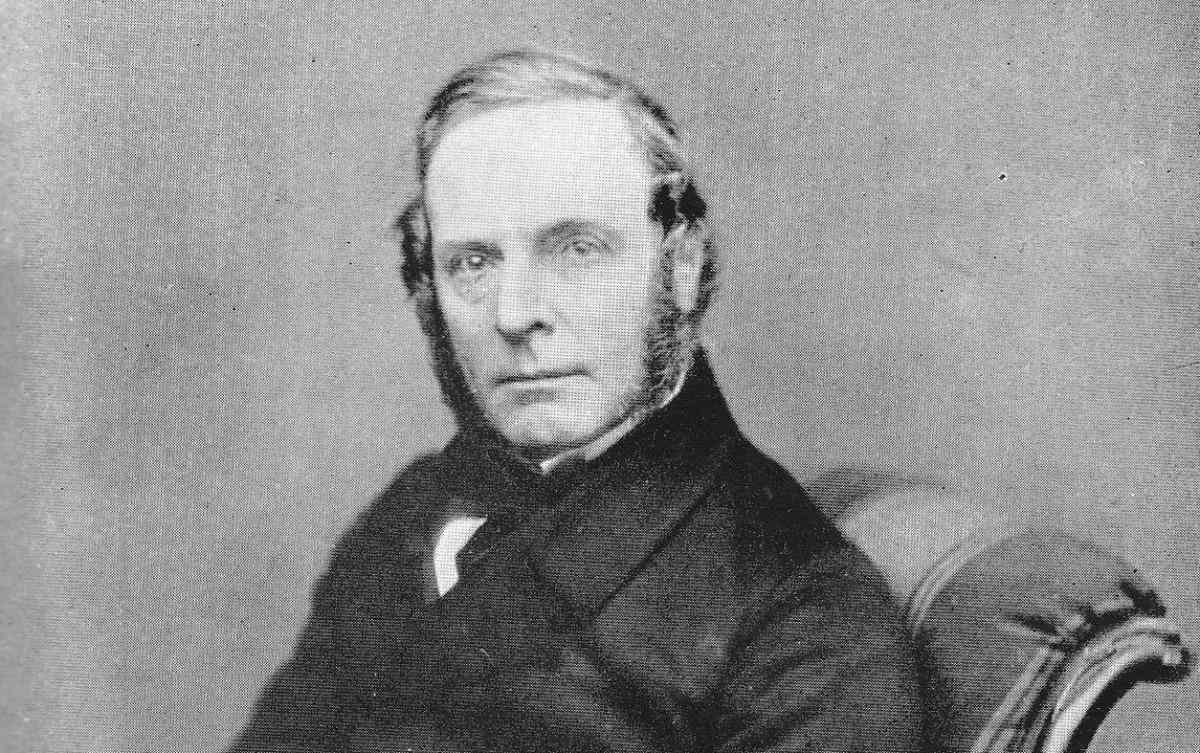

The West’s fascination with a potent new beverage, tea, peaked around the middle of the 19th century. But China was maintaining a 5,000-year monopoly on the product’s commerce and production. To end this, the British embarked on one of the most daring acts of espionage in history. They planned to steal the tea trade secrets from Imperial China. Robert Fortune, a botanist from Scotland who was 36 at the time, was the spy they chose to carry out this task. It is safe to say that there would be no tea in the West for a long time if it wasn’t up to Robert Fortune.

Who was Robert Fortune?

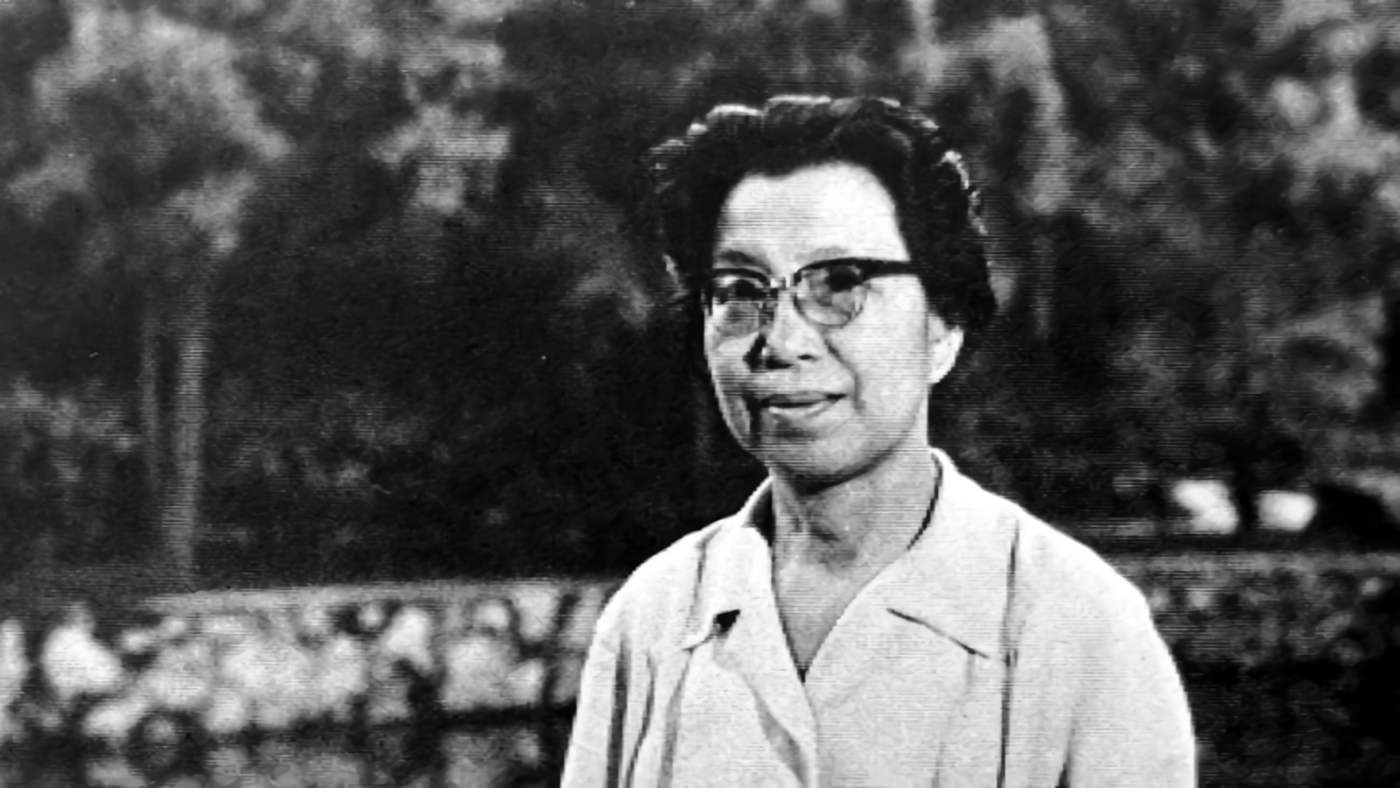

Robert Fortune (1812–1880) was born in Edrom, Berwickshire, Scotland. Fortune started his career in the Edinburgh Botanic Garden, and then in 1840, he moved on to run the orangery at the Horticultural Society’s garden in Chiswick, London. In 1843, after the Treaty of Nanking that ended the First Opium War, he was commissioned by the Society to gather plants in Southern China.

The Society sent Fortune on a plant-collecting—if not stealing—mission to China, with specific orders to bring back plants that were both hardy and exotic. While Fortune was in China for three years, he frequently supplied his employer with new seeds and plants. He was the best choice when the East India Company was seeking someone to bring tea plants from China to India to start a new tea business in the West. He went to China two more times, and the second time was to advise the US government on how to launch its own tea industry. More than 120 new horticultural plant species were brought to Britain as a result of Robert Fortune’s trips to China.

Fortune to unseat China

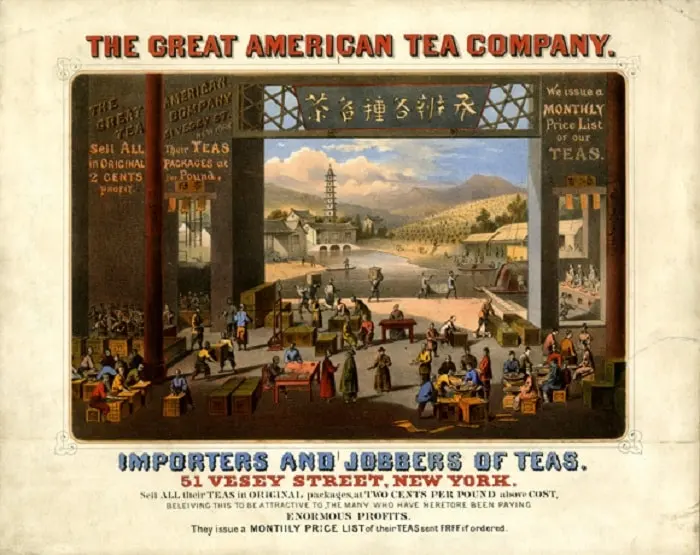

Even though India now consumes and produces more tea than any other country, commercial tea cultivation in India did not begin until the middle of the 19th century. The British East India Company (1600-1874) engaged in a crafty act of biopiracy that facilitated the growth of the tea trade in the East. China was the sole supplier of tea to the West in the early 19th century, and commerce was severely hampered by the country’s insistence on being paid in silver. The Company saw an opportunity to unseat China as the dominant player in the tea sector as demand for the drink increased throughout Europe.

The British attempted to build a plantation using both indigenous Assam tea plants and Chinese seedlings after learning that the tea plant successfully thrived wild in Northeast India’s Assam region. However, neither of the attempts worked. But in 1848, the British East India Company wanted to send a “plant hunter” to China with the goal of acquiring the finest types of the tea plant, and bringing in local producers and supplies for the government’s tea plantation in the Himalayas.

The Royal Horticultural Society sent Robert Fortune, a Scottish plant collector who had visited China for the Society between 1843 and 1846. While there, he examined tea-growing regions and also gathered various plants and tree peonies including Abelia chinensis, Weigela florida, and Platycodon grandiflorus (then known as Campanula grandiflora).

Fortune the plant hunter

Robert Fortune discovered that black and green tea were actually coming from the same plant, and he noticed that the green teas packaged for export were always dyed with Prussian blue, a somewhat hazardous chemical created by combining cyanide acid and iron, and gypsum. This coloring was for the European and American “barbarians” who enjoyed the “beautiful flowers” in their tea. In addition, Fortune noted that the process in which the leaves of the tea bushes are selected and prepared was relatively simple, contrary to popular belief.

20,000 varieties of plants, and skilled producers

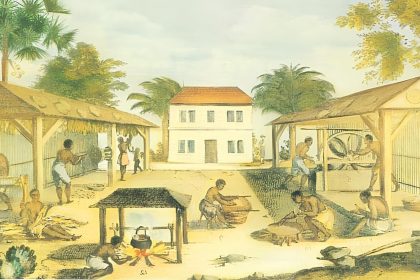

In the year 1848, Fortune set out on a quest to collect tea leaves. He chopped off all but a ponytail of his hair and dressed in traditional clothes so that he would blend in with the locals and be able to go more freely into the country’s interior. On his way to the Hwuy-chow tea district, he walked, took a boat, and rode a palanquin for a total of 200 miles (325 km). In the highlands, Fortune learned about the cultivation of green tea and spent time harvesting its seeds. He journeyed to northern “Hokkien” and other black tea producing areas. Despite the fact that there were more easily accessible tea-producing districts, Robert Fortune was certain that only the highest-quality supplies be sent to India.

His description of the northern Chinese city of Tsong-gan-hien tells a lot. According to Fortune, this city was full of large tea-hongs where black teas were sorted and packed for foreign markets. Traders from all regions in China where tea was consumed or exported were visiting here to buy tea and delicately plan its transportation.

Robert Fortune shipped the tea seeds to Calcutta in ward boxes, which he thought was the finest method for shipping. According to his book, “A Journey to the Tea Countries of China,” he was able to secure nearly 20,000 tea plants, eight first-class tea farmers, and a wealth of tea equipment from the finest tea districts of China to the Himalayas in 1852.

The most profitable heist ever

Robert Fortune predicted that the new tea plantations in Assam and Sikkim would probably prove a tremendous asset not only to India but also to England and her growing colonies. China continued to dominate the tea business far into the second half of the 19th century, but by the 1890s, India was meeting 90% of Britain’s domestic tea demand. India’s tea exports to Britain increased in value from £24,000 in 1854 to £20,087,000 in 1929. Today, there are now 3,300,000 US tons (3 million metric tons) of tea manufactured each year for the global tea demand, making it the most widely consumed soft drink in the world, all thanks to the efforts of Robert Fortune, the mighty “tea spy.” Robert Fortune died at the age of 67 on April 13th, 1880, in London.

Bibliography

- Robert Fortune, “A Journey to the Tea Countries of China,” 1852.

- Dictionary of National Biography, “1885-1900/Fortune, Robert,” 1885.

- Okakura Kakuzō, “The Book of Tea“, 1906.