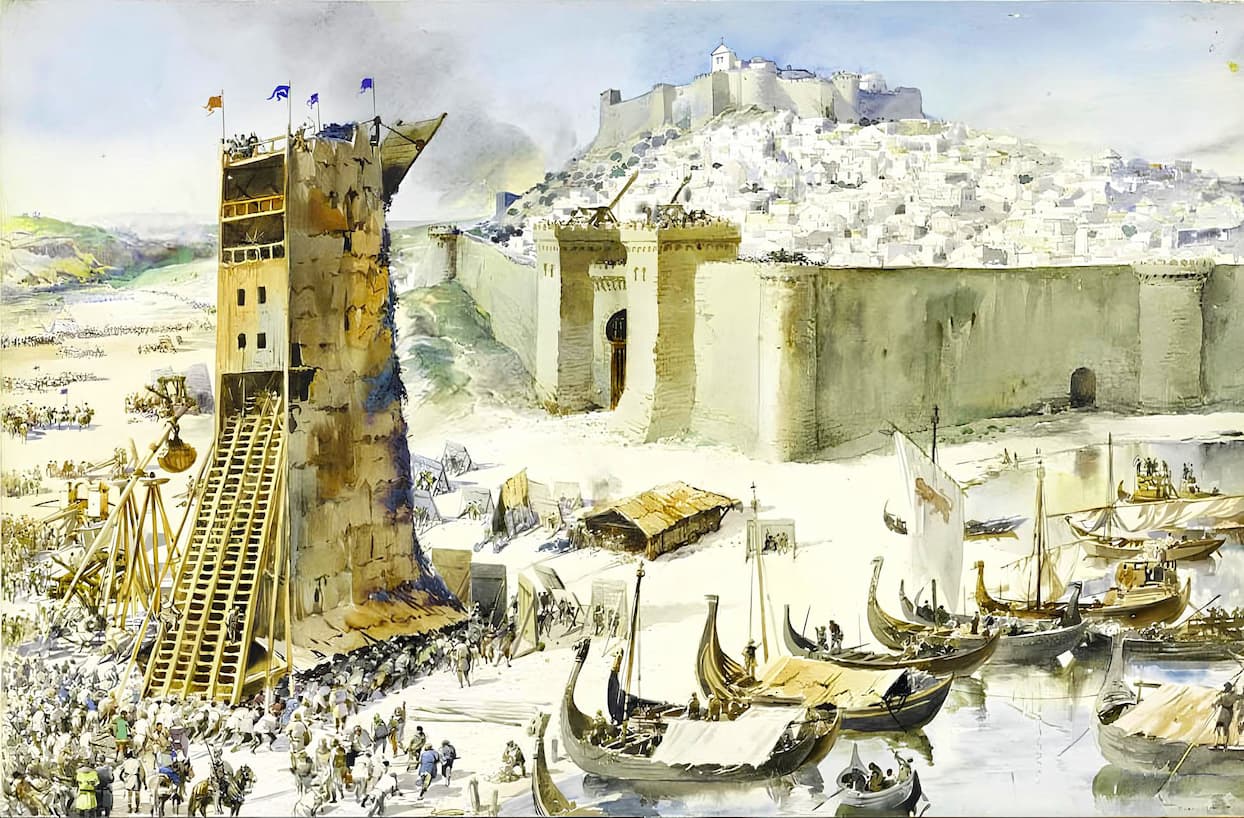

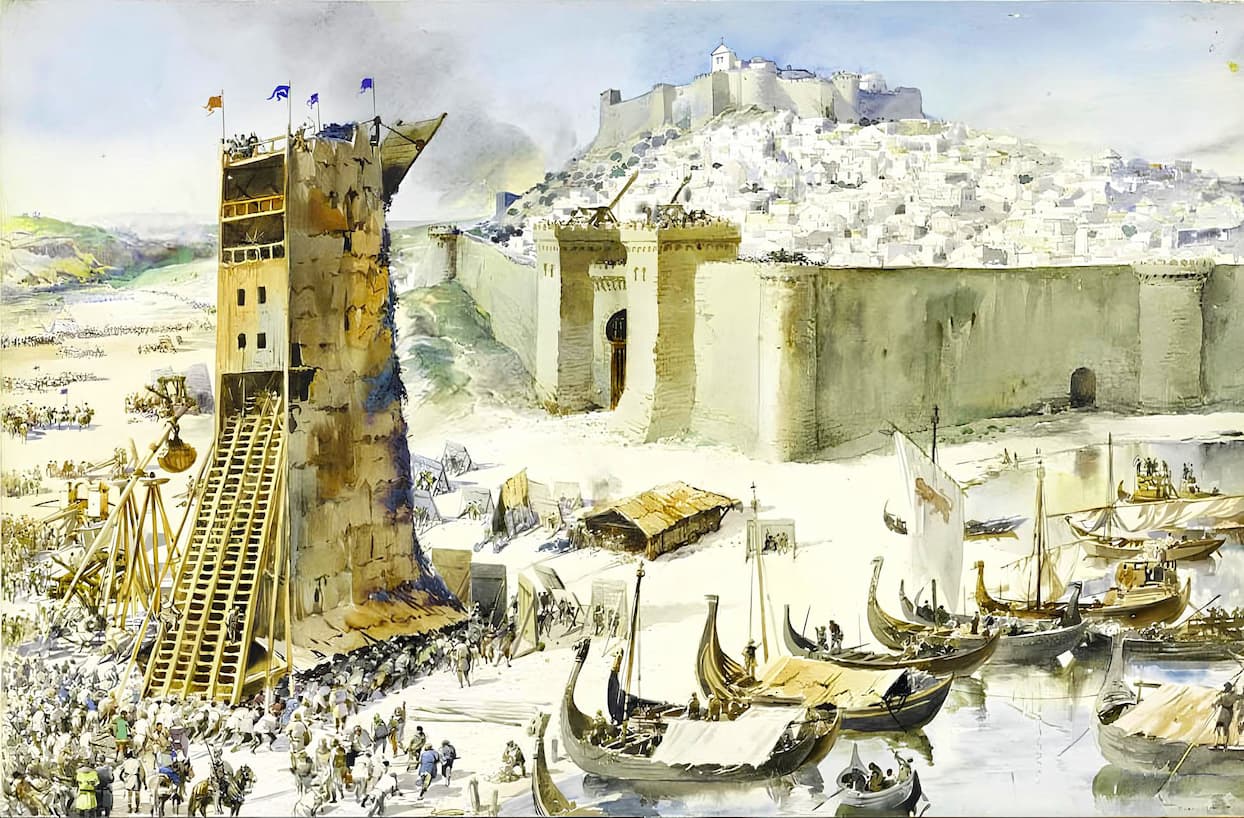

Sieges in Ancient Times

Siege warfare in antiquity became an integral part of warfare at that time following the settlement of people in cities.

Siege warfare in antiquity became an integral part of warfare at that time following the settlement of people in cities.