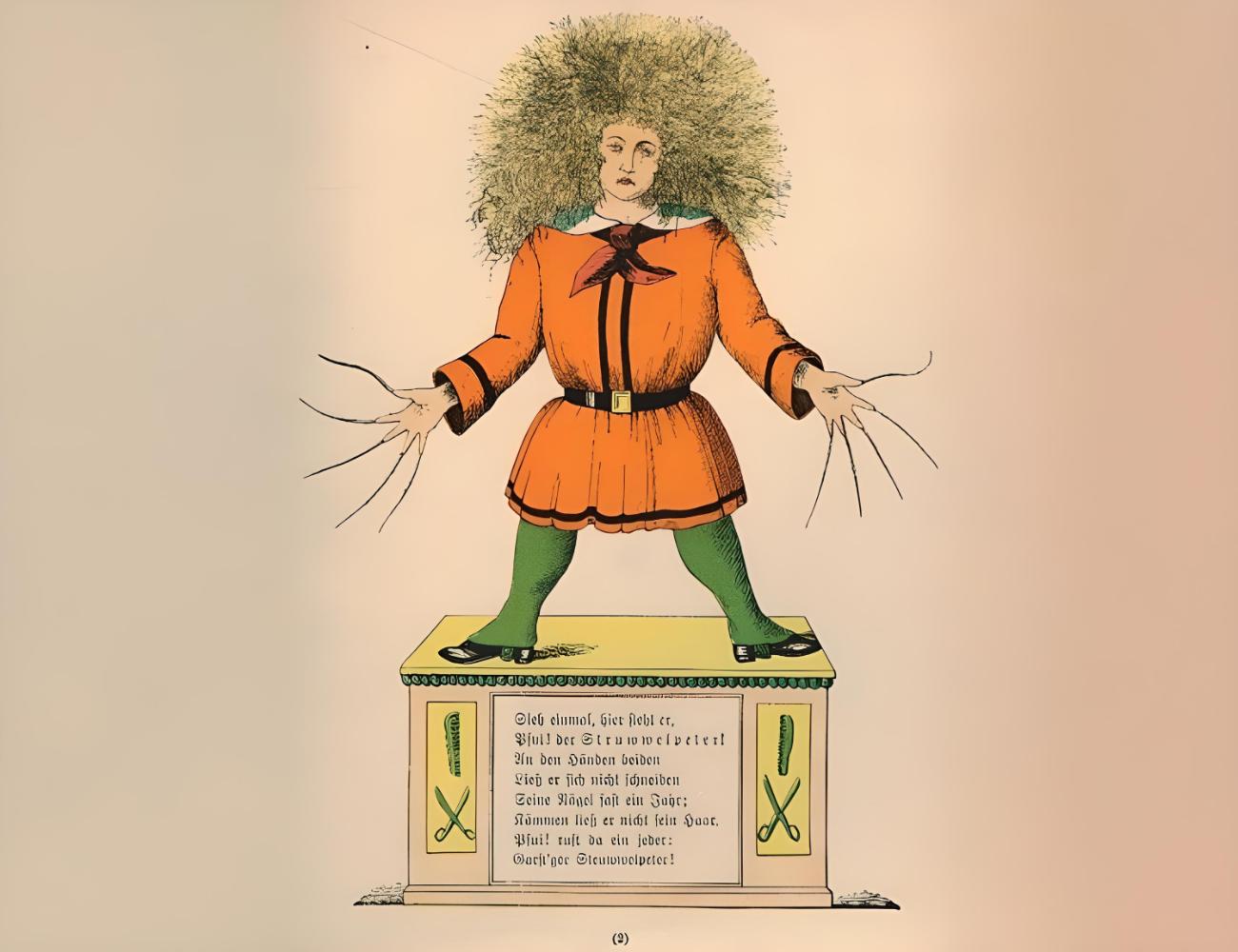

Struwwelpeter is one of the most popular children’s books ever written. And this original Christmas gift has spawned many humorous imitations. In Frankfurt in 1844, Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann was searching for a Christmas gift for his son Carl. Children at that age cannot yet read, hence a picture book was chosen. After searching the city’s bookshops, Hoffmann (1809–1894) was left with only long novels or comical picture collections, realistic illustrations, and plain morals, as he later reflected.

After another futile hunt, Hoffmann eventually went home, this time with an empty notepad. He started doodling and making up rhymes, eventually coming up with the basic concept for “Struwwelpeter.”

Laugh-out-loud anecdotes and cartoons

Formerly known as “Funny Stories and Droll Pictures,” this term is now used as the book’s subtitle. Despite mounting pressure from a variety of quarters, Hoffmann remained unconvinced that he should make the booklet accessible to the public. But his family worried that his small son might eventually rip up the pamphlet anyway. Hoffmann was a member of a group called Tutti Frutti that gathered weekly to hear inspiring speeches and/or musical creations, and they were also pushing for Hoffmann’s work to be published.

In the middle of January 1845, only a few weeks after Hoffmann had delivered the gift to his son, the Tutti Frutti (Italian for “all the fruits”) got together again. Zwiebel, as Hoffmann was known in this community, read his writing, and the fruits were thrilled.

One of them, known by a pen name, Spargel (“Asparagus”), had just co-founded a publishing enterprise with a business partner. He proposed 80 guilders to Hoffmann for the text. Hoffmann concurred. This deal had transformed him into a literary celebrity among teenagers practically overnight.

Struwwelpeter ruled the globe

The first print run of 1500 copies was quickly depleted. Depending on the source, the edition sold out anywhere from one to two months after its release. In short order, the original six were joined by others, such as the tales of Paulinchen, who plays with matches, The Story of Fidgety Philip, and The Story of Flying Robert. Internationally, the piece was likewise met with great acclaim.

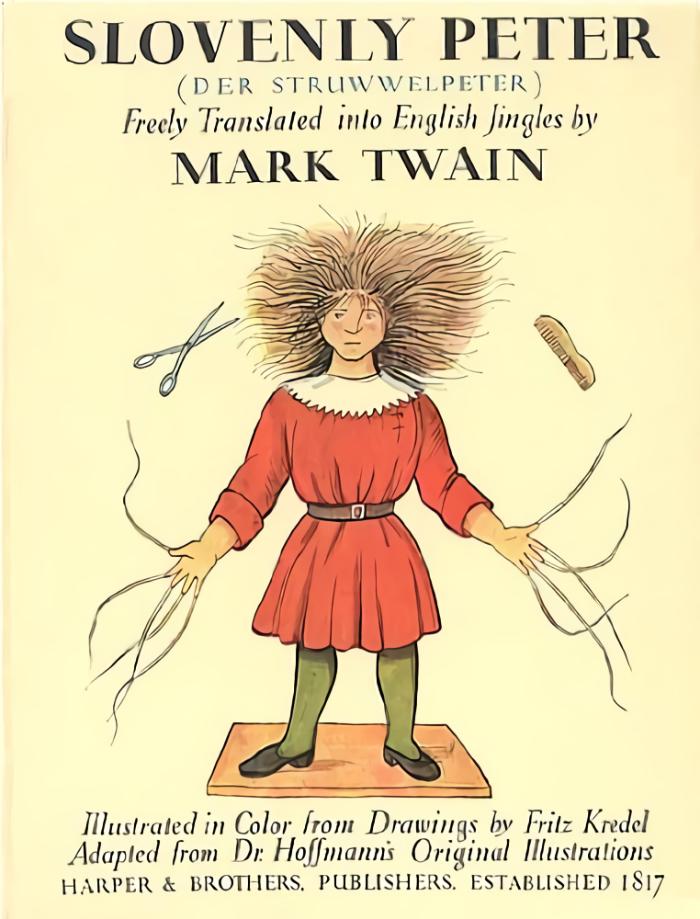

The American adaptation, named “Slovenly Peter,” was penned by none other than the great humorist Mark Twain.

What made Struwwelpeter so popular?

But what made this book such a hit with readers? The two most important explanations have to do with technology and cultural shifts, respectively. By the middle of the 19th century, industrialization had made it feasible to duplicate books at much lower costs. Lithography made it possible to print books without the once-expensive practice of hand-coloring their illustrations.

As a result of societal changes that started at the tail end of the 18th century, middle-class women also had greater time for what we now term “leisure” activities. Furthermore, a larger percentage of adults started to see childhood as a distinct phase of development. This resulted in the publishing industry taking notice of mothers and their children as a new target demographic. This marked the official introduction of children’s books to the mainstream reading public.

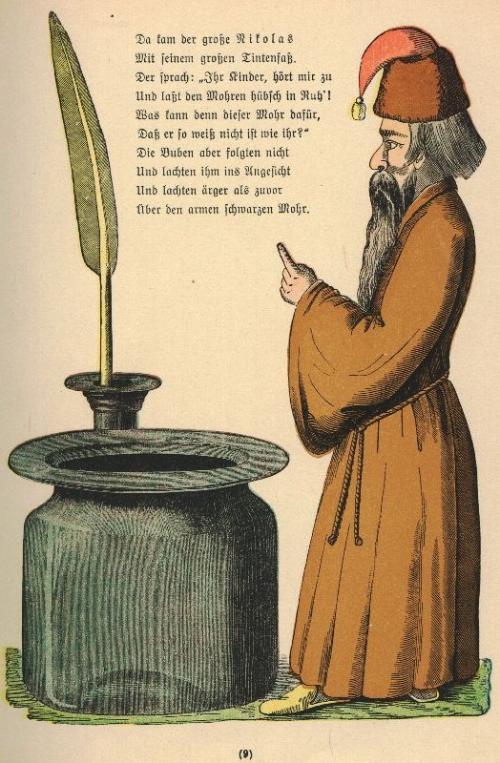

There was a newfound focus on writing and publishing children’s literature. Why, however, did “Struwwelpeter” stand out and become so well-liked? The tales in “Struwwelpeter” presumably struck a chord with readers because they reflected common observations about children at the time and today, such as the refusal of certain children to sit still or eat what is put in front of them or the harassment and intimidation of others, like in the case of The Story of the Inky Boys.

Both the original “Struwwelpeter” and its updated “Struwwelpaula” were featured in a Berlin exhibition back in 1994. Struwwelpaula is an example of a punk character.

However, it’s not just that. Even though they were intended for youngsters, Hoffmann’s illustrations and narrative were designed mainly for adults. The tales’ potential educational value is now a matter of debate. Since the original publication, a sizable body of literature has amassed, and with it, a wide range of opinions and valuations.

The underlying depravity, melancholy, and suffering, according to some, make the work unsuitable for young readers. However, there is another group of people that highlight the chaos, ostentation, and fun that result from Struwwelpeter. Thus, it is not surprising that Struwwelpeter has been the subject of not just countless translations since its inception, but also innumerable parodies and fresh interpretations.

An “Egyptian Struwwelpeter” was in use by the late 19th century. Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach (1830–1916) had an unauthorized print of the book, which was originally written by the three Viennese siblings. Truwwelpeter’s many incarnations are a mirror of society’s shifting mores. For instance, the “Struwwelliese” was written in the 1950s, and the “Struwwelpaula” in the 1990s; in both, a young girl dresses as a punk and travels the nation spraying subway cars with graffiti.

The political versions of Struwwelpeter

Most notably, there was a flood of political parodies. In 1848, the year of the French revolution, there was, for instance, the proper Struwwelpeter in the role of a revolutionary. The “New Reichstag Struwwelpeter” appeared in print in 1903. The Soup Kaspar’s lines, “Don’t let them in. We don’t need a soci, no!” are meant to represent the concerns of the Social Democratic Party’s seasoned political guard after the party’s electoral victory.

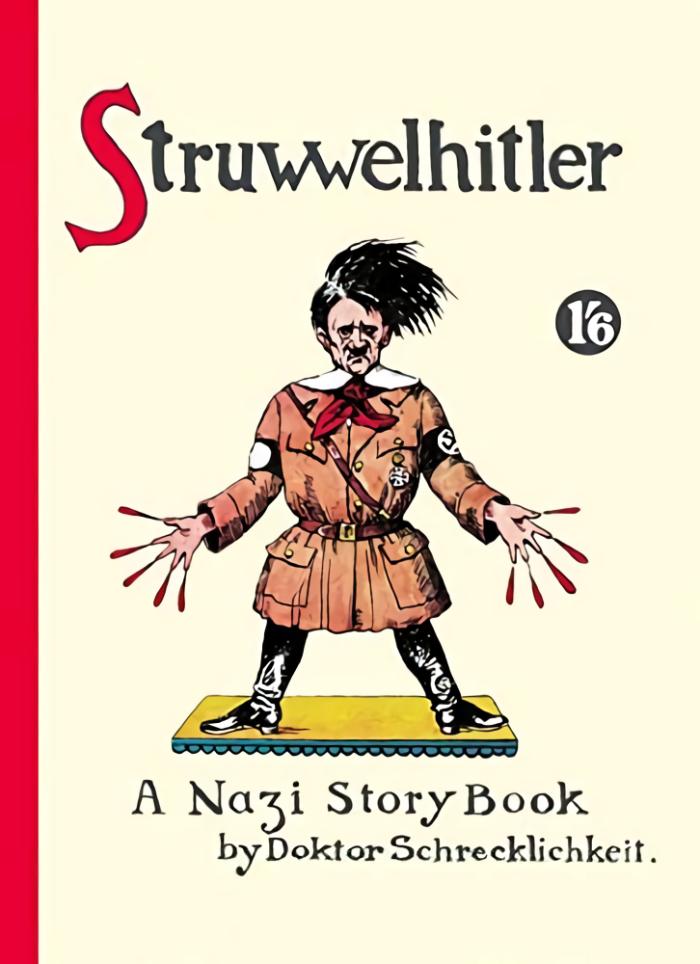

The English brothers Robert and Philip Spence published “Struwwelhitler” under the pen name “Dr. Schrecklichkeit” in 1941, and in 1914 they released “Swollen-Headed William” to mock the German Kaiser Wilhelm II for propaganda reasons. In this book, two writers lampoon Adolf Hitler, Hermann Goring, Joseph Goebbels, and Benito Mussolini.

Before British troops were sent to the mainland, they were handed this book, which had been quickly and inexpensively printed.

The continued relevance of Struwwelpeter

Even though “Struwwelpeter” has taken a lot of heat over the years for making some dubious moral claims, many people still know and enjoy the tales. A new edition was released, and an exhibition was presented at the Museum of Cultural History in Germany in 2022.

Additionally, the Struwwelpeter Museum in Hoffmann’s birthplace of Frankfurt remains a popular destination among visitors. According to a study report written in 2020 by a philologist at the University of Krakow, Struwwelpeter’s continued relevance may be attributed to the work’s ambivalence and ambiguity.