Surus was the elephant that Hannibal personally rode through the crossing of the Alps and during the events after it. It was his favorite animal. The tale of Hannibal’s successful attempt to lead his elephants across the Alps has endured through the ages. During the Carthaginian general’s lifetime, and maybe at his suggestion, Greek historians created a picture of a god-like hero who, with the aid of the gods, led his elephants through ambushes placed by mountain dwellers and across freezing deserts. The elephants are elevated to the status of stars of Hannibal’s expedition thanks to the contributions of medieval romances, the romantic 19th century era, and films of the 20th century. One animal in particular stood out from the rest and it was Surus. It was the strongest of the bunch and the only one to make it through Hannibal’s whole expedition and help Hannibal make it through the Arno marshes while the general was blind in one eye and Surus only had one tusk.

What was the name of Hannibal’s personal elephant?

Surus was known as Hannibal’s most courageous elephant. Hannibal had a deep affection for Surus during and after his campaign in the Alps, until the animal’s death.

Was Surus a Syrian elephant?

Historians are of the opinion that Surus was an Indian elephant whose ancestors were captured by Alexander the Great’s Seleucid successors in the East. It’s still up for debate whether Surus was brought in from India or if it was native to Syria.

Trivia: Surus in video games

In u0022Assassin’s Creed Originsu0022 an animal named Surus can be found and fought during the Dead or Alive mission. In-game, Surus can be found in a ring of combat in the game’s southwestern Green Mountains.

Who was Surus?

The Carthaginian elephants often panicked the horses with their weird look and foreign scent, but they were also foiled by being hit behind their tails. The Carthaginian warriors battled from towers on the backs of the elephants which were probably a lesser forest subspecies of the African elephant.

Surus, which also translates as “Syrian”, was likely an Indian elephant who was regularly ridden by Hannibal himself and was considered the toughest in combat despite having one tusk, and yet he was the only elephant to survive the campaign. Cato, while listing the names of many elephants in his Annals, had to include Surus since he was the elephant who especially fought hardest throughout the Punic Wars. And by the same token, he was missing a tooth.

The ancient Roman poet Ennius used a pun when he said, “one Syrian to carry a stake, nevertheless he could defend.” It was probably a pun on the Latin word for “stake,” “sūrus“, or “sudus” which refers to the long wooden poles that legionaries used to set up barricades while camping. Surus was armed with its own “stake” in the fight against the Carthaginians—its one tusk. Alternately, “Stake” might have been a Roman shortening of Surus’ name. The Roman playwright Plautus said in 191 BC that only the name “Surus” could strike terror into an enemy’s heart; such was the public’s infatuation with the beast.

Surus was also employed to help clear a route through the mountains for the army, and it was taught to carry supplies and equipment as well.

Hannibal’s affection for Surus

When Hannibal led his army into battle on the Arno’s marshy plain, an unbreakable relationship between Surus and his master Hannibal was created. As Livy describes, the four-day march through the water was arduous. The first troops to enter the water, preceded by the guides, faced a perilous journey across the river’s changing bottom and steep-sided holes. They were almost swallowed up by the mud in which they sank. Among the slain mules might be found the bodies of the Gallic auxiliary soldiers, who were initially less hardened and dejected.

By the end, Hannibal was being “carried by the only surviving elephant,” Surus. Hannibal developed ophthalmia shortly after crossing the Alps and eventually lost his one eye. But it was thanks to Surus that Hannibal was able to make it over these awful wetlands. By this time, Surus had only one tusk but he was still bold and proud.

It’s likely that Surus passed away the day before the Battle of Lake Trasimeno on June 21, 217 BC. Even after he finally triumphed, Hannibal was still in sorrow over the death of Surus, his favorite elephant. In a desperate attempt to fill Surus’ place, Hannibal later imported a herd of Spanish elephants, although he evidently did not bond with them as well as he did with Surus.

In August 216, the elephants were sent into the Battle of Cannae on August 2, 216 BC, in southern Italy, where they were slaughtered by Roman soldiers, who assaulted them with blazing firebrands and set fire to the wooden towers housing the archers. The European employment of elephants as auxiliary troops came to an end with Hannibal’s loss in North Africa at the Battle of Zama in 202 BC. The elephants were cumbersome and slow to move; they also wore out rapidly, and most importantly, they did tremendous damage to their own ranks in the conflict of the battle. Their demise predicted the fall of Carthage in 146 BC.

What species was Surus?

The Syrian or Western Asiatic elephant (Elephas maximus asurus) was a subspecies of the Asian elephant that was formerly widespread in the ancient Middle East but later became extinct. They were often put to use in combat and transportation. As a result of excessive poaching for their ivory, elephants became extinct about the year 100 BC, much later than the demise of Surus.

During the Punic Wars (264-146 BC), various Carthaginian generals, including Hannibal Barca, used elephants in battle against the Romans. The majority of Hannibal’s 37 elephants were the extinct North African kind. Compared to their Syrian counterparts, they were noticeably smaller.

Surus, an Asian elephant with a single tusk, was reportedly the largest and most impressive of Hannibal’s elephants. After making it across the Alps (218 BC), it was also the last of its kind to do it. African elephants are seen on a Carthaginian coin from Hannibal’s reign.

Historians, however, are of the opinion that Surus was an Indian elephant whose ancestors were captured by Alexander the Great’s Seleucid successors in the East. It’s still up for debate whether Surus was brought in from India or if it was native to Syria.

Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps led to the story of Surus

Conflicts between Carthage and Rome, known as the Punic Wars, took place between 264 and 146 B.C. Hamilcar Barca, the patriarch of a prominent Carthaginian family, led his people to victory in southern Spain after the Romans had driven them from Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica. His son Hannibal took over the Carthaginian army in Hispania in 221 BC, a few years after his father’s death. He was only 26, yet he vowed an unending enmity against Rome. Since his brother-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair was in charge of Spain, in the spring of 218 he set out for Italy with between 75,000 and 100,000 troops and 37 elephants (according to Polybius’s account, the first detailed account of the war that we have).

The Carthaginians had used elephants as part of their military for some time now. They were not the pioneer war elephants either. India’s early and widespread adoption of them is notable. When the Greek king of Epirus, Pyrrhus, came to Italy and subsequently Sicily with his elephants in the first part of the 2nd century, the Romans and the Carthaginians were forced to deal with them. The top officials of Carthage recognized the value of these creatures and made sure their empire had access to them. This was a simple task, since the elephants were abounding in the south of modern-day Tunisia and elsewhere in the Maghreb, where forest cover was still substantial. Unlike their African bush elephant counterparts, who might grow to be 13 feet (4 meters) tall and weigh up to 5 tons, these elephants seldom grew to be taller than 10 feet (3 meters).

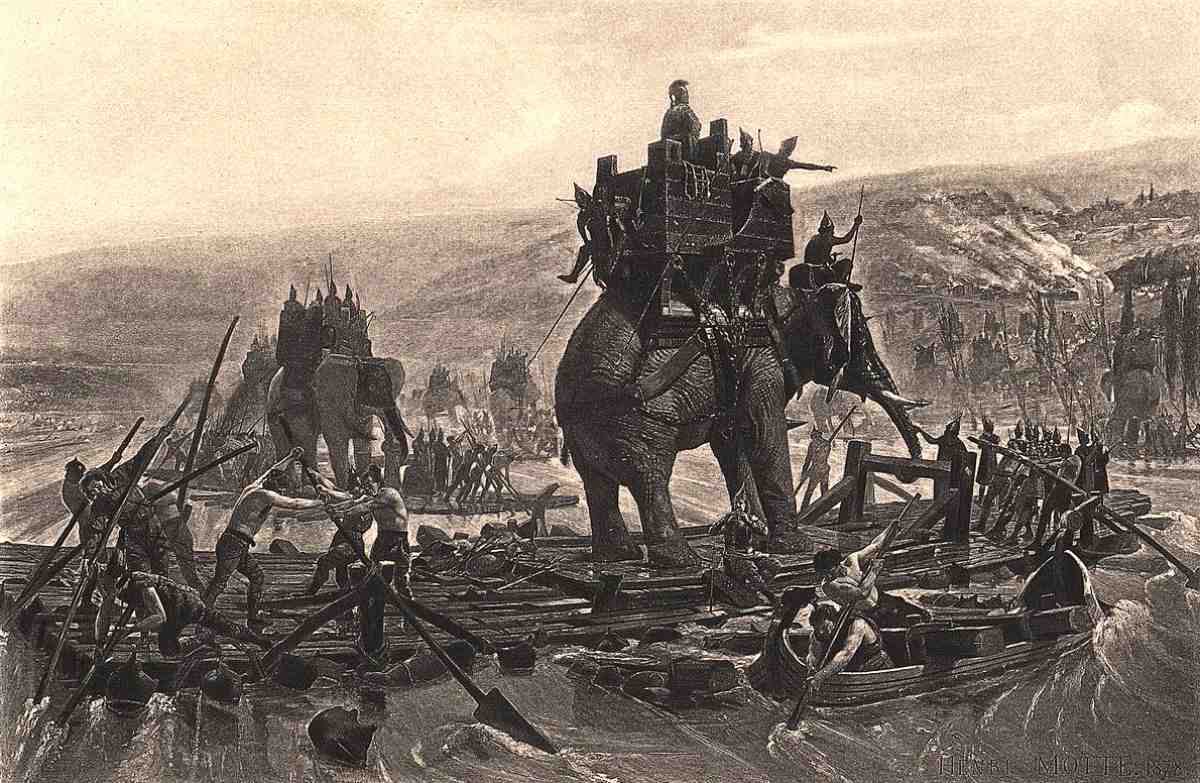

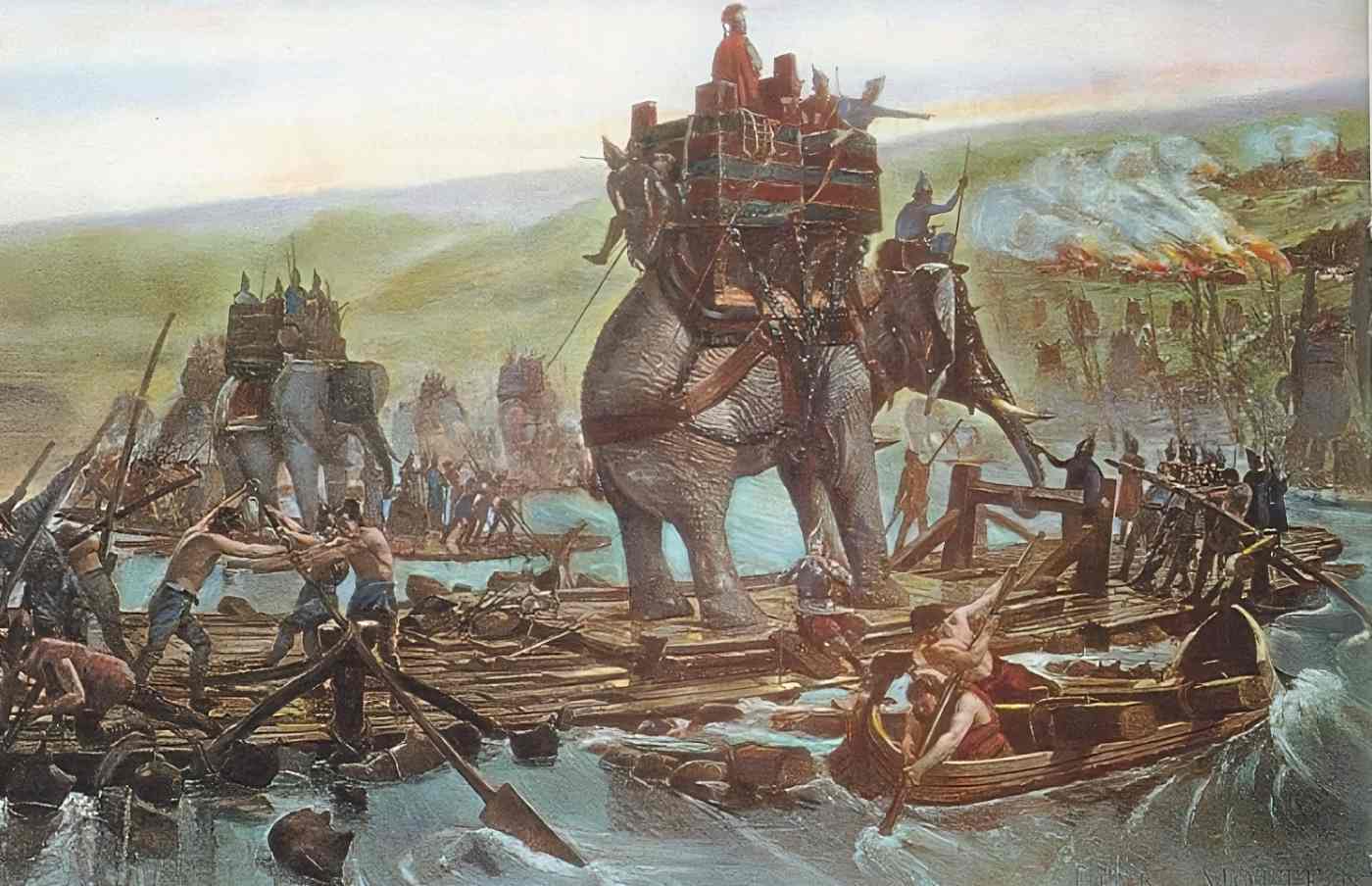

Hannibal had high hopes for the elephants because of how easy they were to tame. They could carry bags, clear the way of obstacles like boulders and trees, and even go into fights to help out like war tanks. Most importantly, they would shock and frighten unsuspecting civilians and enemy soldiers alike. The Carthaginian army left in the spring of 218 AD, crossed the Pyrenees Mountain range, marched over the plain of Languedoc, and by August had reached the River Rhône. In order to get away from the Roman soldiers who had landed in the delta, they had to swim the river and then climb the Alps. These were the challenges that the elephants would have had trouble surmounting if they had been better equipped.

Engineers under Hannibal’s command built massive rafts, which they secured to the bank by burying them in dirt and grass. The elephants were fooled by their looks (and maybe drawn there by the females that the mahouts, the elephant riders, put there initially). When the moorings were broken and the rafts were hauled into the water by pulling boats, the situation became much more dire. Fearful elephants grouped together, and some were swept away by the current. However, by using their trunks as snorkels and walking along the river bank, the remaining elephants were able to reach dry ground. It was a terrifying passage.

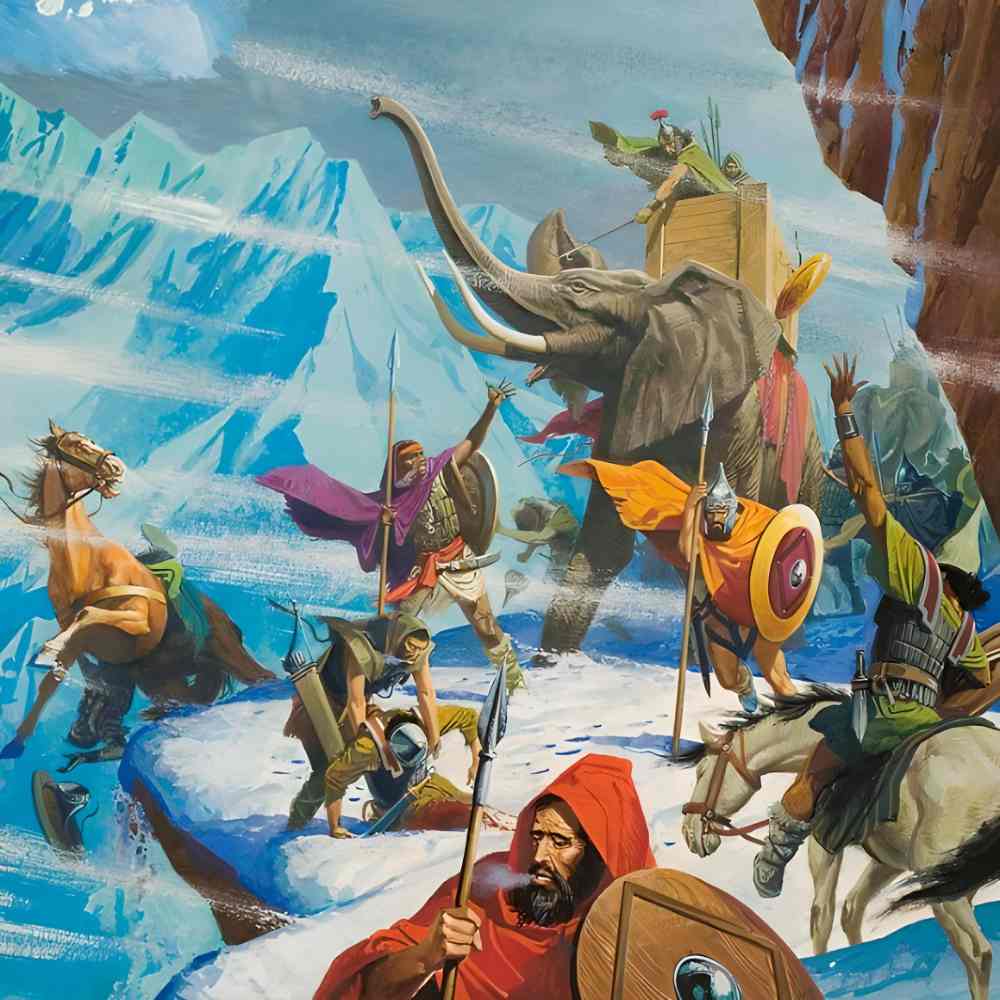

The Alps provided a unique path for the elephants and the Carthaginian army, maybe through the Maurienne and the Mont Cenis Pass (we still do not have any certainty on the route taken). It took Hannibal’s army 15 days to traverse the mountain because they were harassed by hostile people and had to contend with cold, wind, and snow. The descent was more challenging than the climb since it was “narrow, steep, and covered with snow,” as described by Polybius.

If one missed the true path, one would fall into terrible precipices. Fearful and hopeless, the whole army gave up and surrendered when they reached a spot where it was impossible for the elephants or the horses to advance due to the sinking ground. What occurred was, without a doubt, a one-of-a-kind occurrence: “The new snow which had fallen on the top of the old snow remaining since the previous winter, was itself yielding,” wrote Polybius.

“When they had trodden through it and set foot on the congealed snow beneath it, they no longer sunk in it, but slid along it with both feet, as happens to those who walk on ground with a coat of mud on it.”

Surus was the only surviving elephant

While sinking, the elephants dug themselves into tunnels that now imprisoned them. Here, somewhere around 19 of the elephants perished despite the best efforts of Gallic troops who had joined the Carthaginians and who had encircled the elephants with all their care after getting over their first dread of the massive animals. The Syrian, or Surus, which also means “butterfly” in Punic, refers to the most hardy and resilient animal among the Carthaginian elephants of Hannibal. Because, despite all, Surus was the only surviving elephant of the expedition.

Surus’ huge ears, when wide apart, presumably brought to mind the wings of the lovely insect. It has been speculated, but not proven, that this elephant called Surus, unlike the others, originated in Syria or India, and was transported to Egypt’s Memphis before being sold or purchased by Hannibal at Carthage.

The Carthaginian commander Hannibal, accompanied by a somewhat diminished force, landed in Italy and started making his way south toward Rome. Near the Ticino and Trebia, two streams of the Po, he met the Roman troops and emerged triumphant. Hannibal ordered his elephants to charge on the banks of the Trebia, but the Romans, who were no longer frightened of elephants, had adapted to the point that they could hurl javelins and arrows at the animals, chop off their hocks with axes, and lop off their trunks with scythes. There were at least five elephants lost. During the harsh winter in Liguria, the other elephants succumbed to the elements and lack of food. In the spring of 217, when the Carthaginians invaded Etruria, only the elephant Surus was left alive among Hannibal’s elephants.

Bibliography

- Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, BOOK VIII. THE NATURE OF THE TERRESTRIAL ANIMALS. Tufts.edu.

- “Magister Elephantorvm”: A Reappraisal of Hannibal’s Use of Elephants on JSTOR

- THE MYSTERY OF HANNIBAL’S ELEPHANTS – The New York Times

- Ido Yahalom, 2018, The Carthaginian Elephants and their Handlers: Only African Forest Elephants and Local Personnel.