The Termidor Reaction is the name given to the period of the French Revolution that begins on July 27, 1794, with the fall of Robespierre, and ends on October 26, 1795, when the Constitution of the Year III establishes the French Directory. It takes its name from the National Convention, the name of the parliament at that time, and follows the Mountain Convention, the period of the French First Republic dominated by the Jacobins.

The name “Thermidor” comes from one of the summer months in the republican calendar and refers to 9 Thermidor Year II (July 27, 1794), the date of Robespierre’s fall, which led to the dominance of the conservative republicans, precisely called Thermidorians.

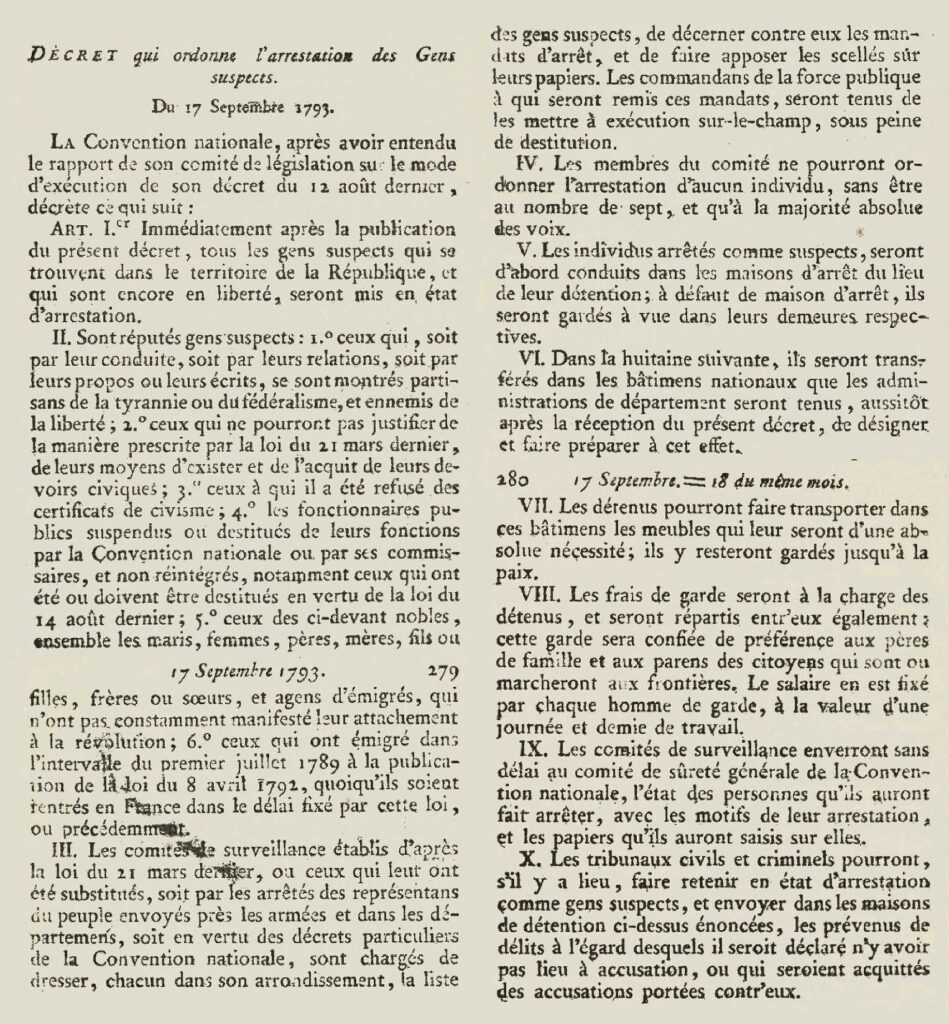

Also: Law of Suspects: How It Shaped the French Revolution

The Thermidorian Reaction did not lead to the restoration of the monarchy. Instead, it led to the establishment of The Directory, which was a more conservative republican government.

Causes of the Thermidorian Convention

The Thermidorian Convention resulted from a combination of factors that created an atmosphere of discontent and distrust towards Maximilien Robespierre and the Committee of Public Safety, who had wielded dictatorial power since the onset of the Reign of Terror in September 1793. Among these factors are:

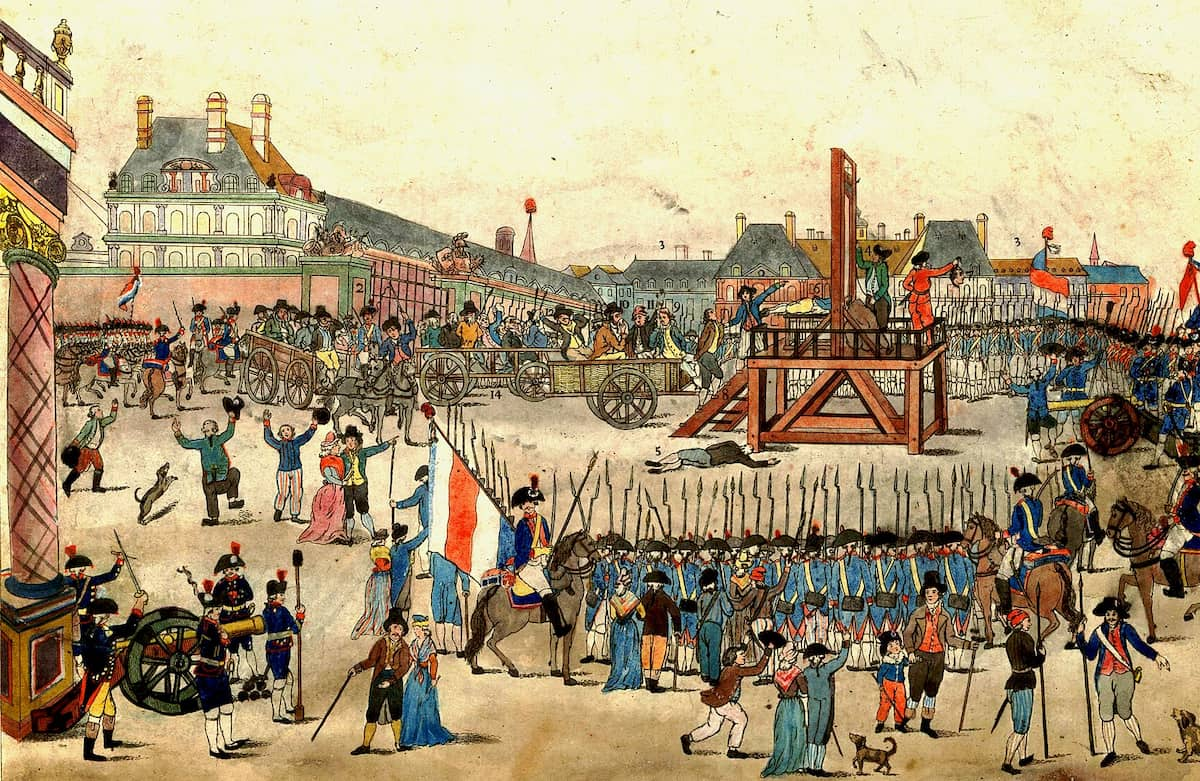

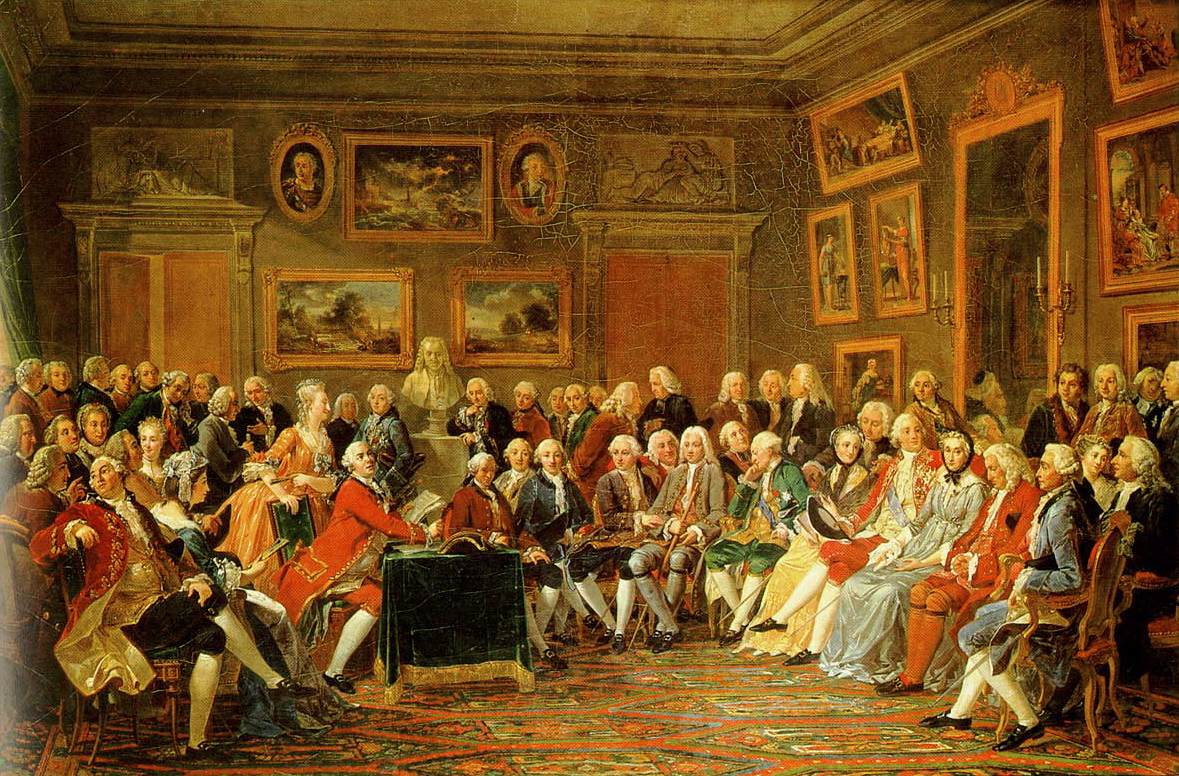

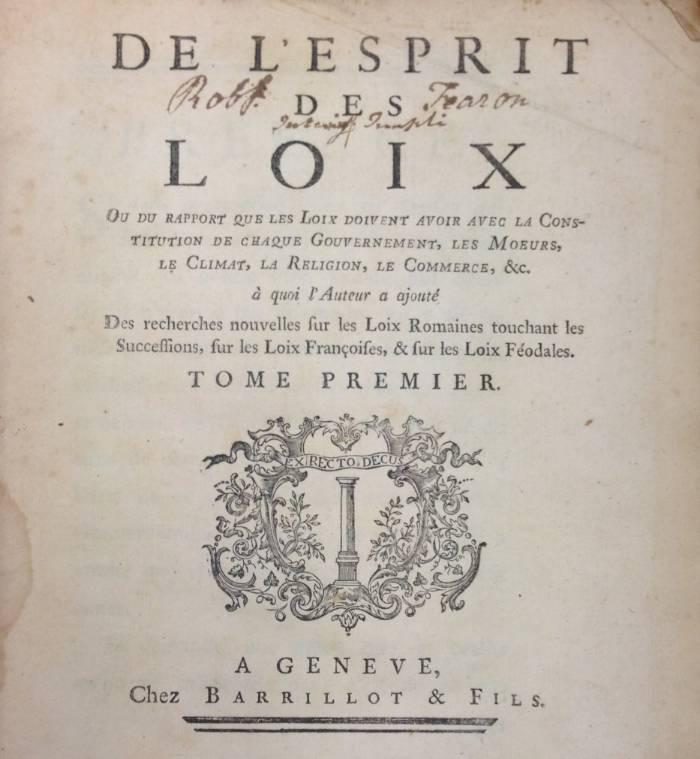

Public weariness of the violence and repression of the Reign of Terror, which claimed thousands of lives, especially among moderates, Girondins, Hebertists, Dantonists, Sans-culottes, refractory priests, nobles, and royalists. The Reign of Terror also imposed unpopular economic and social measures such as the Law of the Maximum, which regulated prices and wages, and dechristianization, an attempt to replace Catholic worship with the Cult of the Supreme Being.

Diminished external threats as a result of French military successes against European coalitions. The victory at Fleurus on June 26, 1794, pushed Austrian and Prussian forces out of French territory and led to the reconquest of Belgium. This reduced the need for a government for public safety and encouraged aspirations for peace and stability.

Internal divisions within the National Convention pitted the Montagnards (Robespierre’s supporters) against the Thermidorians, which included moderates, former Girondins, former Dantonists, and members of the Committee of General Security who feared for their lives. The Thermidorians accused Robespierre of authoritarianism, fanaticism, isolation, and personal ambition. They also charged him with betraying the ideals of the Revolution and seeking to establish a dictatorship.

Key Figures in the Thermidorian Convention

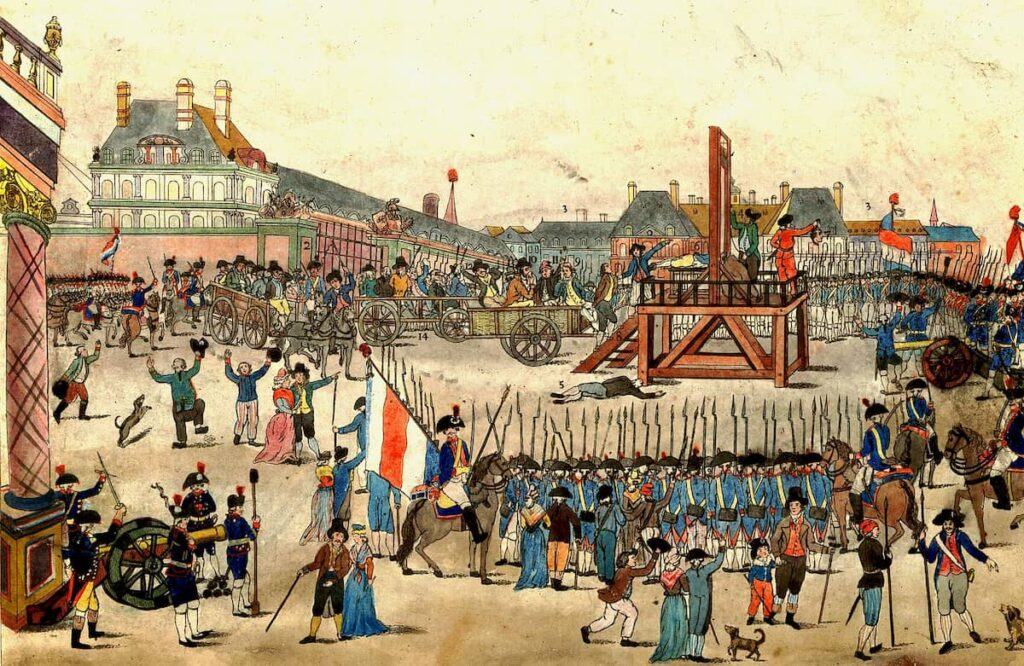

The Thermidorians orchestrated a coup d’état that led to the Thermidorian Convention. They took advantage of a session of the National Convention on 9 Thermidor, Year II (July 27, 1794), to denounce Robespierre and his supporters and have them arrested. Key figures in the Thermidorian Convention include:

- Paul Barras, a member of the Committee of Public Safety, led Convention troops in suppressing Robespierre’s supporters barricaded at Paris City Hall. Barras played a decisive role in capturing and executing Robespierre and his allies on 10 Thermidor, Year II (July 28, 1794). He later became one of the five members of the Directory, the new regime established in 1795.

- Jean-Lambert Tallien, a deputy in the National Convention, who was one of the first to speak out against Robespierre during the July 9 session. He accused Robespierre of being a tyrant and called for his arrest. Tallien also participated in the storming of Paris City Hall and was one of the signatories to the accusation against Robespierre. He was a leader of the moderate faction and supported the Directory.

- Joseph Fouché, a deputy in the National Convention, played a significant role in orchestrating the July 9 coup d’état. He mobilized the Paris sections, which favored Robespierre’s downfall, and contributed to the desertion of the Commune’s troops, who remained loyal to Robespierre. Fouché also participated in the attack on Paris City Hall and was one of the signatories to the accusation against Robespierre. He was a leader of the moderate faction and later served as Minister of Police under the Directory.

Consequences of the Thermidorian Convention

The Thermidorian Convention marked the end of the Reign of Terror and the beginning of a new phase in the French Revolution characterized by a return to a more moderate and liberal regime. Consequences of the Thermidorian Convention include:

- The End of Mass Executions and the Release of Political Prisoners: The Revolutionary Tribunal, the primary instrument of the Reign of Terror, was abolished, and its judges were removed from office. Survivors of factions eliminated during the Reign of Terror, such as the Girondins, Hebertists, or Dantonists, were rehabilitated and allowed to resume their positions in the National Convention.

- The End of Radical Economic and Social Measures and a Return to a Capitalist System: The Law of the Maximum, which regulated prices and wages, was repealed, and the market was liberalized. Dechristianization, an attempt to replace Catholic worship with the Cult of the Supreme Being, was abandoned, and freedom of religion was reinstated. National properties were confiscated from the Church and emigrants were auctioned off, benefiting the bourgeoisie.

- The Decline of Montagnard Influence and the Strengthening of Moderate Power: The National Convention was purged of Robespierre’s supporters, and the Thermidorians took control of key committees. The Sans-Culottes, supporters of direct democracy, and the people were repressed and lost their political influence. The Constitution of the Year III, adopted in 1795, established the Directory, a regime based on census suffrage that excluded the working class from voting.

Conclusion

The Thermidorian Convention was a major event in the French Revolution, ending the Reign of Terror and paving the way for a more moderate and liberal regime. It resulted from a coup d’état led by the Thermidorians, who ousted Robespierre and his supporters, taking power in the National Convention. This event brought about political, economic, and social changes that marked a departure from the previous period and set the stage for the rise of Napoleon Bonaparte, who overthrew the Directory in 1799 and established the Consulate and later the Empire.