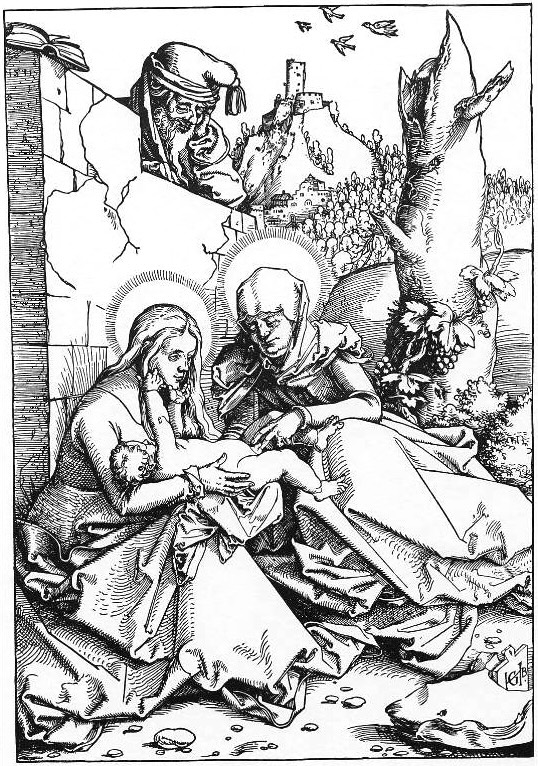

In Hans Baldung Grien’s engraving, we see familiar figures: the infant Jesus, the Virgin Mary, her mother St. Anne, and St. Joseph, Mary’s husband. Yet, something strange is happening. Mary is holding Jesus on her lap, while Anne, under Joseph’s gaze, leans in and touches the child’s genitals.

Art historians explain this scene as either a “domestic vignette” or a magical ritual. But why would an artist depict such a medical examination when it involves not just an ordinary child, but the newborn Savior? Why show the Holy Family under the sway of superstitions?

Medieval people were much more frank in discussing sexual matters than we might assume today. They understood very well that if Jesus was incarnated as a male and not a female, it raised certain questions: Was he truly a man in every sense? Did he experience desire? Did he remain a virgin? Could he become a father?

Art does not shy away from these doubts. The scene where someone examines the genitals of the young Jesus is not merely the product of Baldung Grien’s twisted imagination. His engraving is just one of many works where artists aimed to emphasize the sex of the Divine Infant.

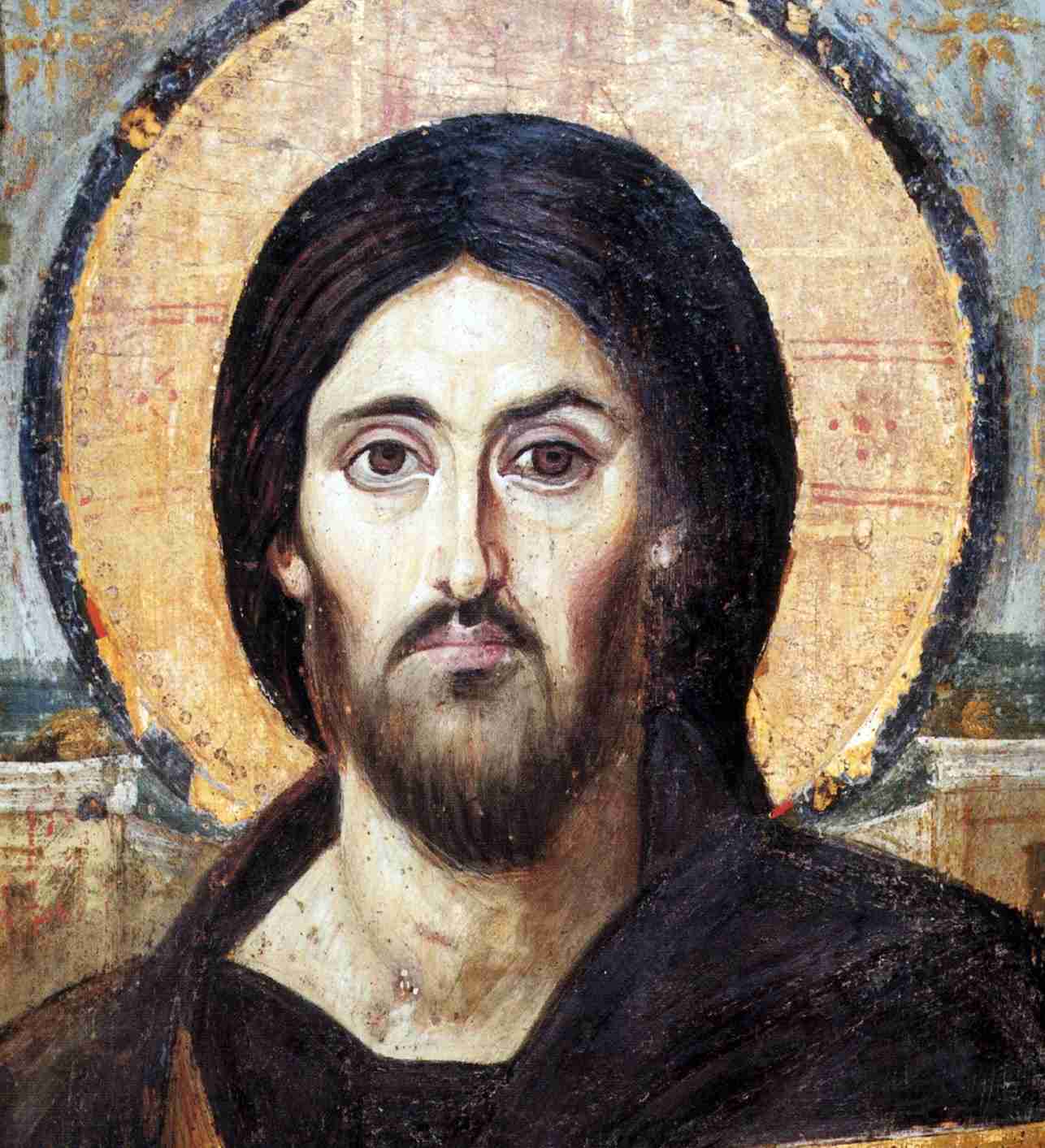

Christ as a Man

In 1983, American professor Leo Steinberg published a book with the intriguing title “The Sexuality of Christ in Renaissance Art and in Modern Oblivion.” In it, he drew attention to something long known but so familiar that it had gone unnoticed: after 1260 in Italy, artists began to depict the infant Jesus nude. Some would lift the hems of his garments to reveal his legs, others would dress him in a transparent tunic, or fully expose his torso.

By the early 15th century, a naked infant, whether in a Nativity scene or in depictions of the Madonna holding him, had become quite commonplace. But that wasn’t all—by the latter half of the same century, European art developed numerous methods to draw the viewer’s attention to the sexual organs of the young Jesus. In Byzantine art, only exposed hands and feet of the infant were depicted, and that too, rarely.

Artists were inventive: sometimes, for unclear reasons, the infant’s tunic would suddenly rise, or his tunic would abruptly end. Jesus might reveal his covering or clothes himself to show us that he was a boy and not a sexless being. Sometimes the Virgin Mary assists him in this; in other instances, she covers his genitals, but this gesture still directs the viewer’s attention to specific body parts.

Although in the Middle Ages, as today, small children were often (especially in summer) left naked, the number of naked infant Jesuses in European art from the 14th to the 16th century is too large for such a motif to be explained merely by observations of reality. Artists don’t depict everything they observe—they choose. For instance, in no medieval depiction do we see the infant Jesus crawling, although infants usually move that way, and no one ever saw anything wrong with it.

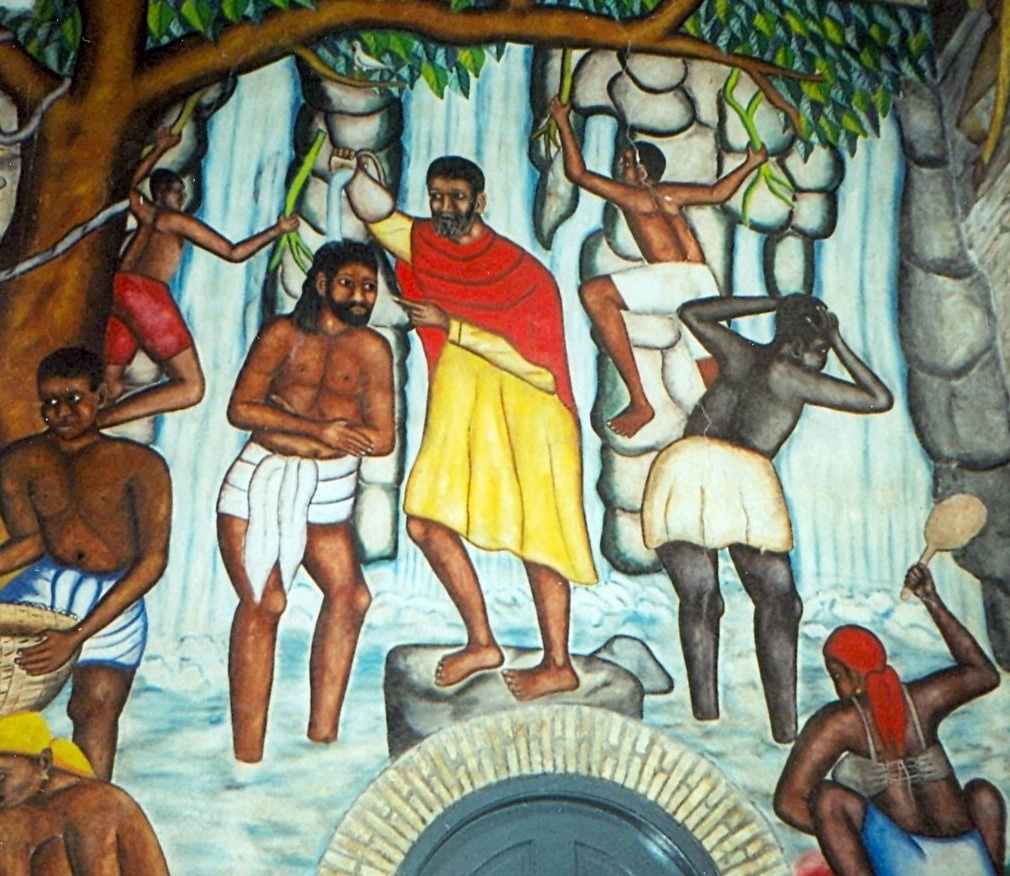

Therefore, the origins of the images of the naked Christ child should likely be sought not in daily life but in theology. The popularity of such images may have been influenced by the preaching of the Franciscans—an order that was incredibly influential in the 14th and 15th centuries. They constantly emphasized that Christ was not only God but also man, and their slogan was “nudus sequi nudum Christum”—”naked follow the naked Christ.”

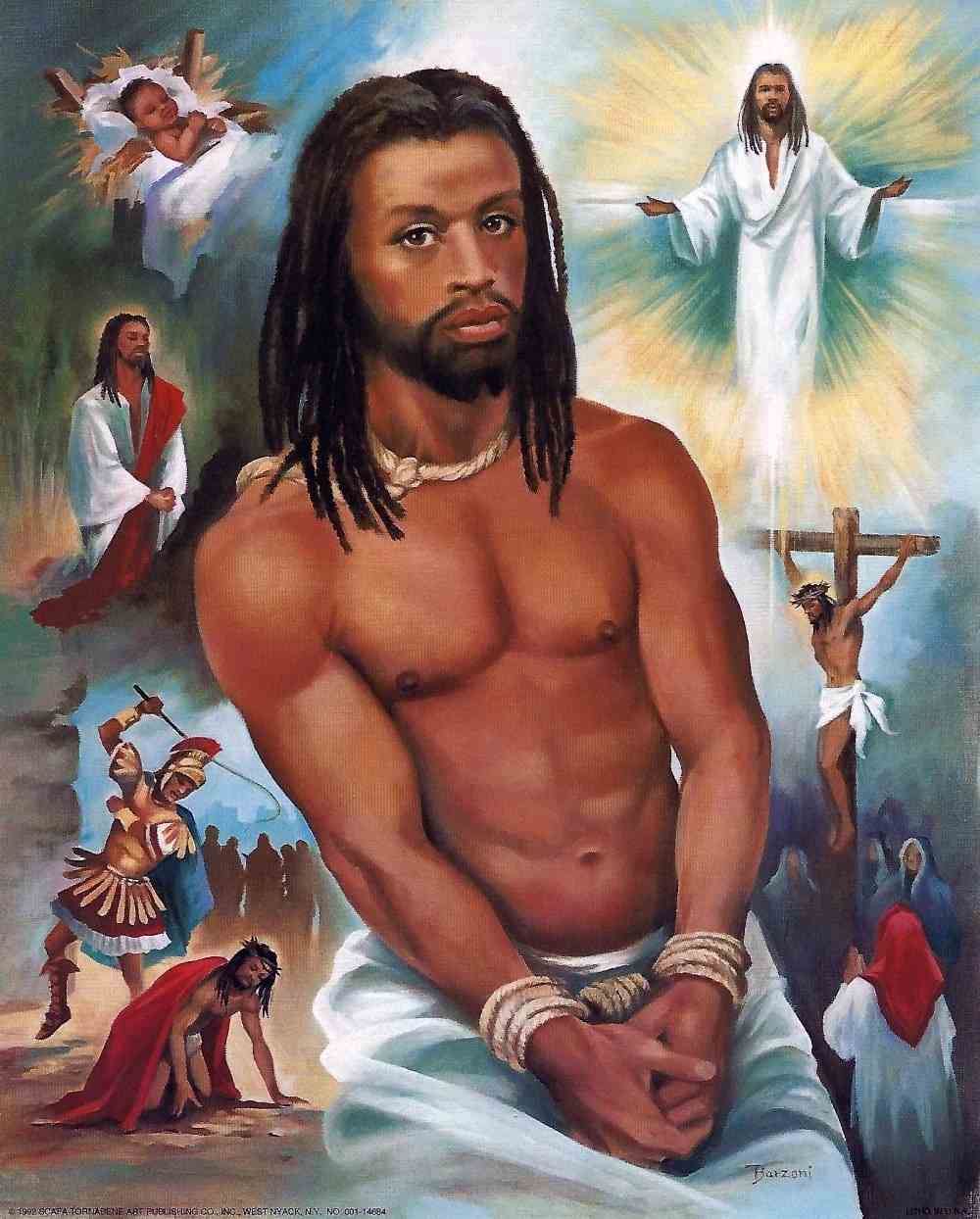

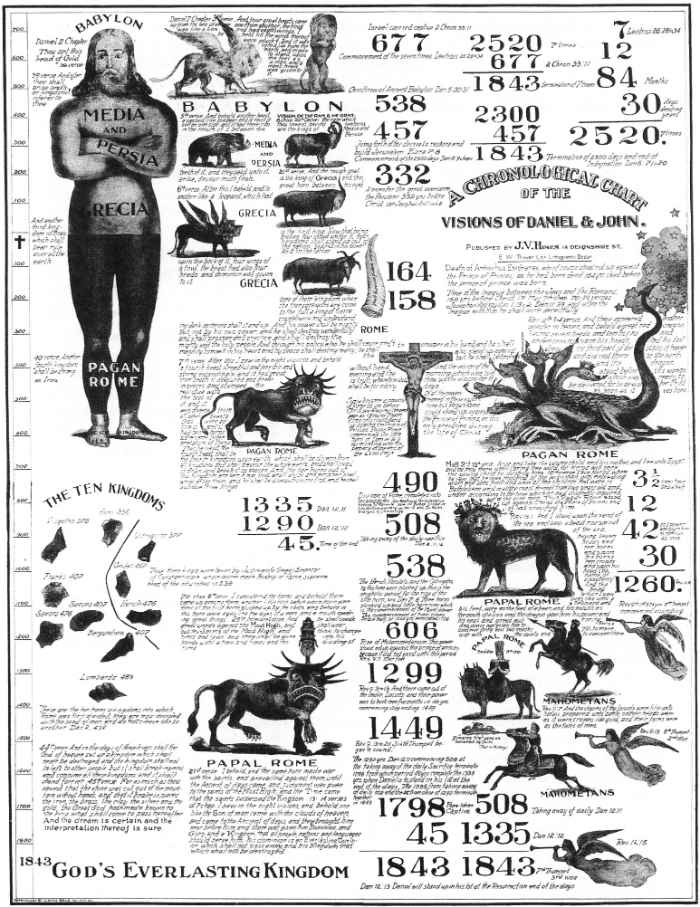

In the religious life of the late Middle Ages, the suffering Savior’s human aspect comes to the forefront—first as a man, then as God. The humanity of Christ was constantly discussed in theological treatises intended for learned clerics and sermons directed at the laity. They reminded people that the path to salvation for every believer was opened by Jesus’ crucifixion. However, to die, God had to fully become a man. Thus, artists strove to show not only the divine but also the earthly nature of Christ, demonstrating that, like other people, he possessed gender and the ability to reproduce.

The connection between human mortality and the ability to reproduce was repeatedly noted by Christian theologians. The eternal God is not subject to death and does not engage in reproduction. However, upon becoming human, He had to be capable of dying and leaving descendants.

For when our first parents sinned in Paradise, they forfeited the immortality which they had received, by the just judgement of God. Because, therefore, Almighty God would not for their fault wholly destroy the human race, he both deprived man of immortality for his sin, and, at the same time, of his great goodness and loving-kindness, reserved to him the power of propagating his race after him.

The Venerable Bede. “Ecclesiastical History of the English People.” Circa 731 [Link]

Of course, before the Fall, Adam could also have children. But this ability only became crucial for the preservation and subsequent salvation of humanity after he was expelled from paradise. Jesus assumed precisely this fallen human nature with all its possibilities and limitations, which likely explains some of the unusual details in his depictions. Of course, unlike all other people, he is not tainted by original sin. But he willingly accepted its consequences—carnal desire, pain, and death.

Adam and Eve, before the Fall and before they became mortal, were naked and unashamed of their nakedness. Similarly, Christ, free from original sin, may not be ashamed of his nakedness. If so, the common gesture of the Madonna covering Jesus’ genitals with her hand may not have been a concession to propriety, but rather an attempt by the mother to protect her human son from impending suffering and death. In some depictions, the infant himself covers his genitals or touches them.

Doubting Shepherds

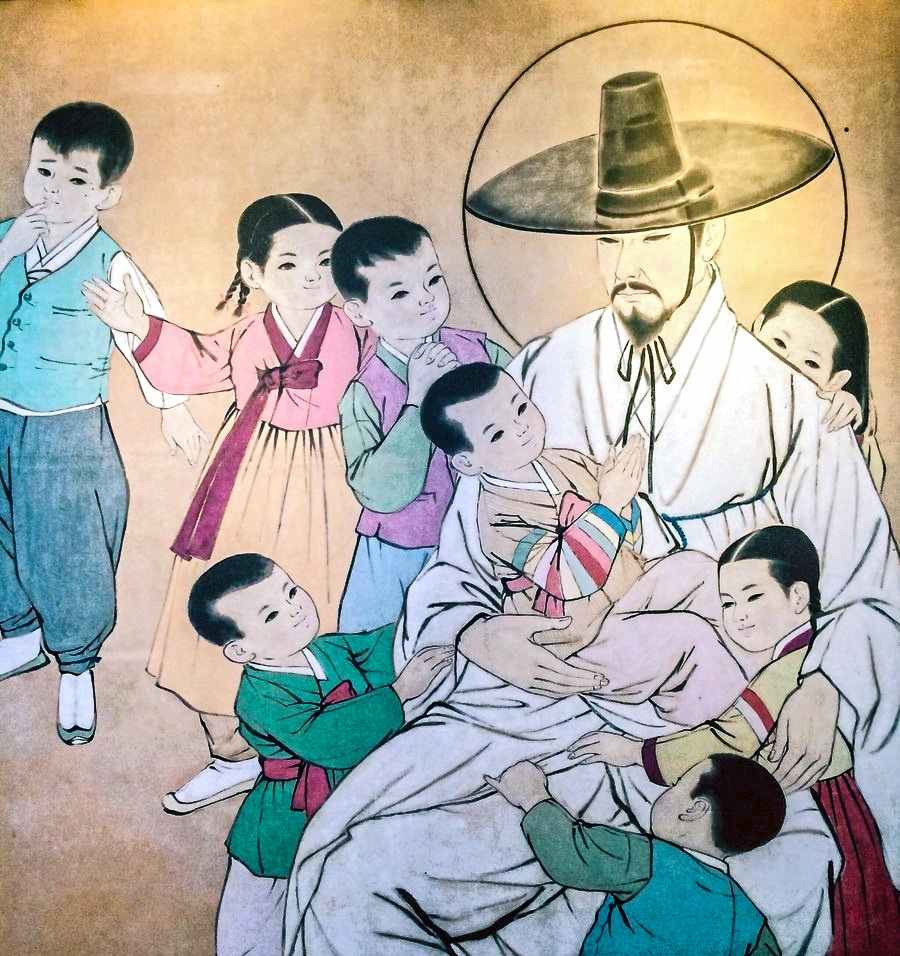

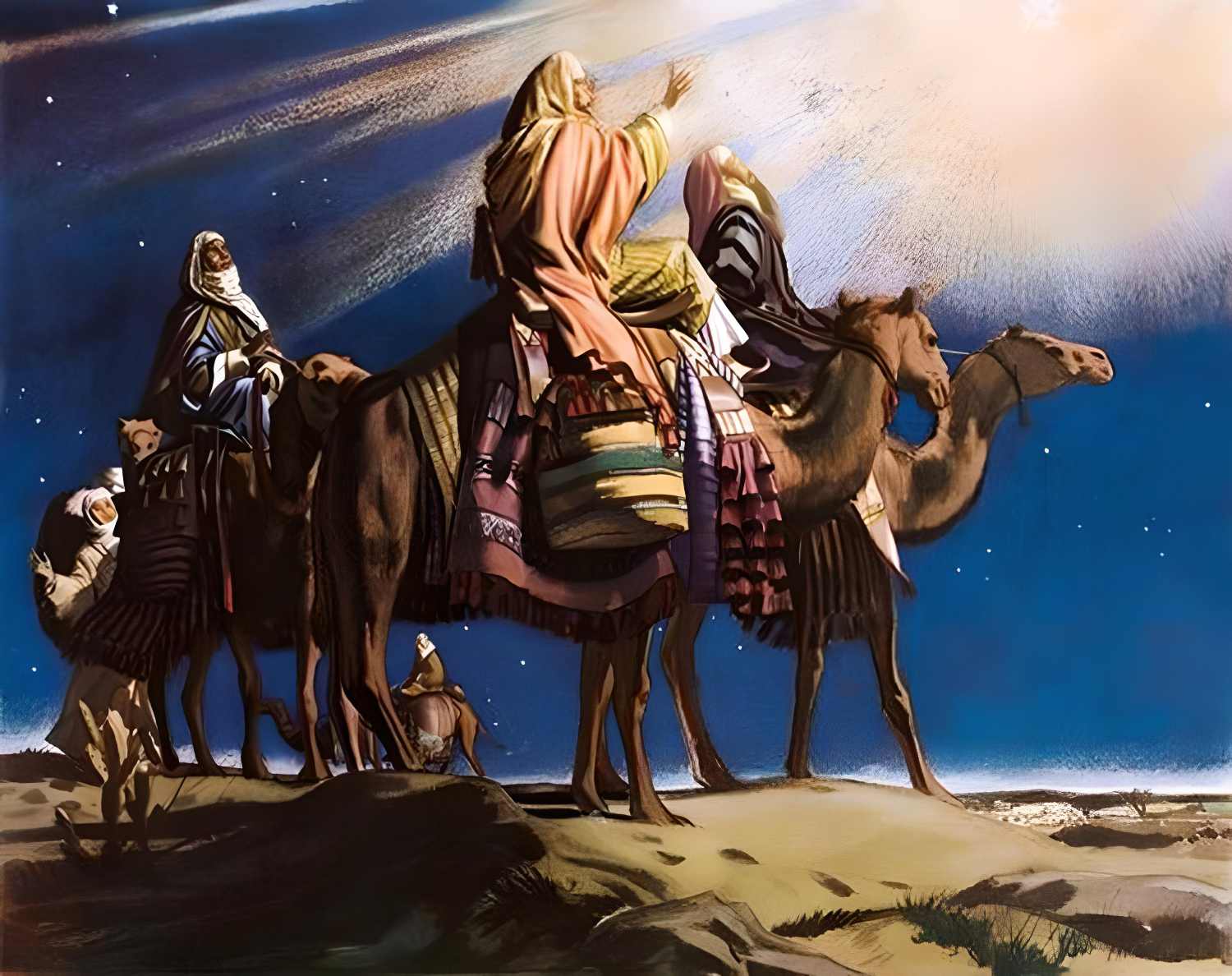

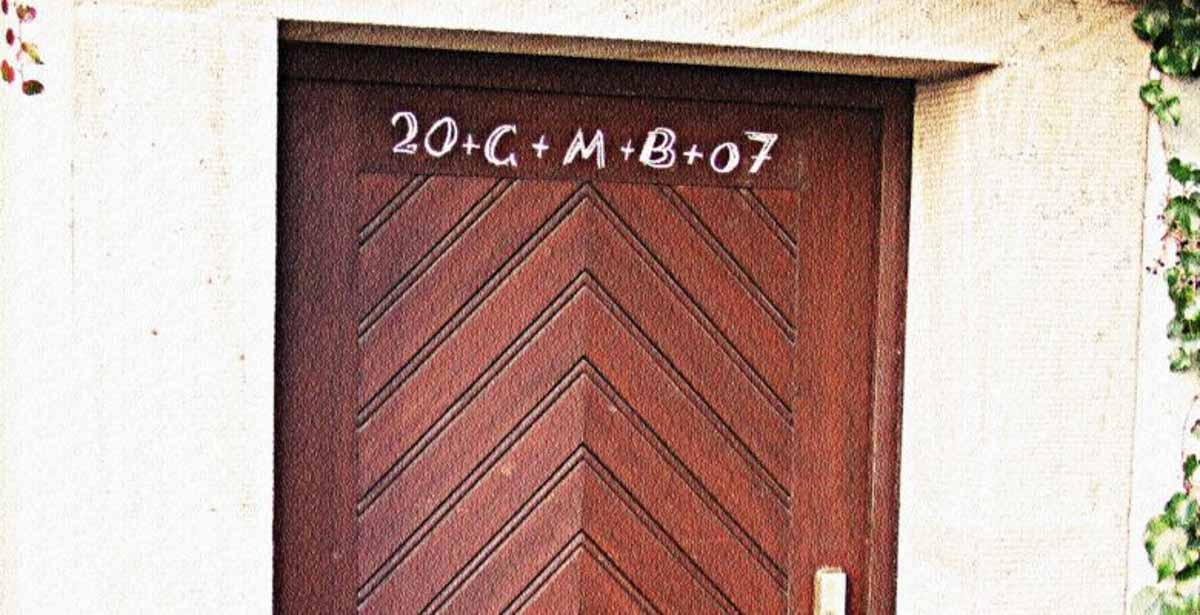

One of the most famous female mystics of the late Middle Ages was Bridget of Sweden (1303–1373). Among her numerous revelations was a vision of the Nativity, emphasizing the importance of Christ being incarnated specifically in a male body. According to Bridget, the shepherds who came to worship the Divine Infant wanted to know who was born, a girl or a boy (since the angels had told them that the savior of the world, not a savior, had been born). Upon finding out, they left, praising the Lord.

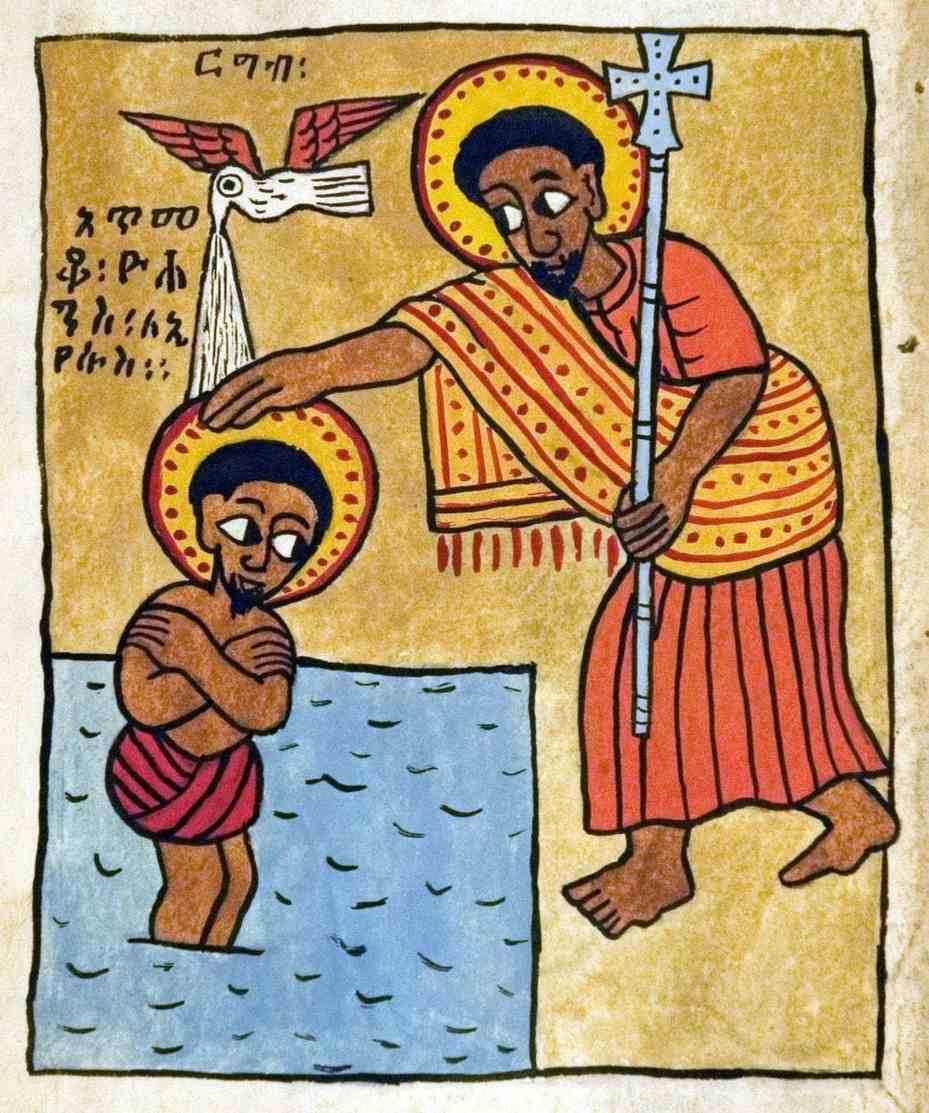

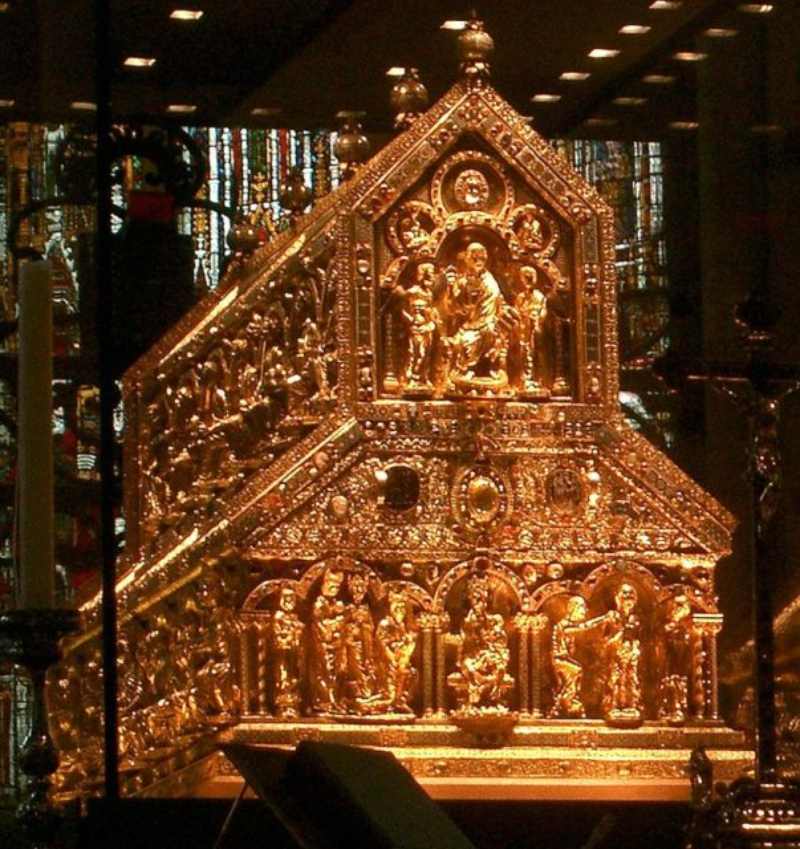

According to the Gospel of Luke (2:21), on the eighth day after the Nativity, the Divine Infant was circumcised, and “he was named Jesus, the name given by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.” Already in the 6th century, the Church established a feast in honor of this event—the Feast of the Circumcision of the Lord (January 1), and theologians began to teach that the cutting of Jesus’ foreskin was his first “installment” in the redemption of all Christians from the power of sin and death. The Church Fathers argued that, unlike other clueless infants who undergo circumcision, Jesus on that day first shed blood for people voluntarily; he allowed himself to be circumcised to set an example of obedience to the Law and, according to Bernard of Clairvaux (1090–1153), to obtain “proof of true humanity” on his body. Thus, circumcision became the first step toward the Passion of Christ, the beginning of the sacrifice.

Scenes of Christ’s circumcision, rare in early medieval art, became increasingly popular in the 14th and 15th centuries. In many cases, this event (through details emphasizing the Child’s suffering: blood and a large knife) visually corresponded with the Crucifixion. The Virgin Mary is always present in depictions of circumcision. This was not mentioned in the Gospel text. Her involvement directly contradicted medieval Jewish traditions—according to which, mothers were forbidden to be present at their sons’ circumcision (Christian theologians believed the same rules applied to Jews in the Gospel times). There is even a miniature where the Virgin Mary performs Jesus’ circumcision herself.

The active role of the Mother of God can be explained either by the fact that artists, depicting the infant, almost “automatically” included his mother in the frame (after all, someone had to hold him), or by the fact that they (together with their theologian “consultants”) were guided by the scene of the Crucifixion, in which Mary always stood at the foot of the cross. The first sacrifice of Christ was depicted after the model of the last.

Betrothal with God

In one of the visions of Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), an Italian religious figure later recognized as a Doctor of the Church (only four women have received such an honor), Jesus spiritually betrothed her by placing on her finger a ring made from the cut-off part of his foreskin.

Your unworthy servant and the slave of Christ’s servants is writing to you in the precious blood of God’s Son. I long to see you a true daughter and spouse consecrated to our dear God. You are called daughter by First Truth because we were created by God and came forth from him. This is what he said: “Let us make humankind in our image and likeness.” And his creature was made his spouse when God assumed our human nature. Oh Jesus, gentlest love, as a sign that you had espoused us you gave us the ring of your most holy and tender flesh at the time of your holy circumcision on the eighth day.

You know my reverend mother, that on the eighth just enough flesh was taken from him to make a circlet of a ring. To give us a sure hope of payment in full he began by paying this pledge. And we received the full payment on the wood of the most holy cross, when this Bridegroom, the spotless Lamb, poured out his blood freely from every member and with it washed away the filth and sin of humankind his spouse.

Catherine of Siena. Letter to Joanna, Queen of Naples, August 4, 1375

Images depicting the circumcision of Christ demonstrate the connection between redemption and masculinity. However, it is very important to note that although Jesus was a man, like his mother, he remained a virgin. But this was not the virginity of a eunuch; it was virginity as a triumph over sin, just as the resurrection is a triumph over death. The surprising and even shocking details in the iconography of the infant Jesus may have a quite canonical theological foundation.

This more perfect Adam, Christ—more perfect because more pure—coming in the flesh to set an example of your weakness, offers Himself to you in the flesh, if only you accept Him, a man completely virginal.

Tertullian, On Monogamy, around 213 AD

“So what did the Lord, the truth and the light, do when He came [into the world]? He, having taken on flesh, kept it incorrupt—in virginity.”

Methodius of Olympus, The Banquet of the Ten Virgins, late 2nd – early 3rd century [Link]

This, says he, I wish, this I desire that you be imitators of me, as I also am of Christ, who was a Virgin born of a Virgin, uncorrupt of her who was uncorrupt. We, because we are men, cannot imitate our Lord’s nativity; but we may at least imitate His life… When difference of sex is done away, and we are putting off the old man, and putting on the new, then we are being born again into Christ a virgin, who was both born of a virgin, and is born again through virginity.

Jerome of Stridon, Two Books Against Jovinian, around 393 AD [Link]

It is not accidental that Jesus was depicted naked not only in infancy but also in death. This, however, required greater boldness from the artist (after all, this is the nudity of an adult, not an infant) and often resulted in public disapproval.

But let us return to the engraving by Hans Baldung Grien. Before us is the embodied symbol of faith—God truly became man. The guarantee of complete incarnation is St. Anne, Jesus’ grandmother by flesh. As she touches her grandson from below, Jesus touches his mother’s chin. This almost imperceptible gesture had quite a specific meaning for the medieval person. But what was it?