During the time of the Roman Empire, there was a period known as the Severan Dynasty. This era had a series of emperors who made various impacts on the empire. One of these emperors, Elagabalus (originally named Varius Avitus Bassianus), became a symbol of the controversies of that time.

The Severan Dynasty was a period of change in the Roman Empire, starting with Septimius Severus in AD 193. He was renowned for his military skill, and his rule established a dynasty that included his descendants Caracalla, Geta, and, as we’ll discuss in this article, Elagabalus.

Elagabalus, born in AD 204, stepped into the world of imperial politics when he was quite young, which was different from the usual experienced Roman rulers. When he became the Roman emperor, his rule was known for its focus on religion, immoderate behavior, and many scandals.

Before Elagabalus, there was another emperor named Marcus Aurelius Antoninus, also known as Caracalla. Caracalla was known for being quite brutal, even going so far as to order the killing of his own brother, Geta, in 211 AD. During his rule, he focused a lot on military actions and strengthening his authority. One notable thing he did was grant Roman citizenship to almost every free citizen living in the Empire through something called the Constitutio Antoniniana, or the Edict of Caracalla, in 212 AD.

Elagabalus: Early Life and Ascension

Emperor Elagabalus, originally named Varius Avitus Bassianus, was born in AD 204 into a well-known family connected to the ruling Severan Dynasty. His early life had circumstances that would later lead him to become the Roman Emperor.

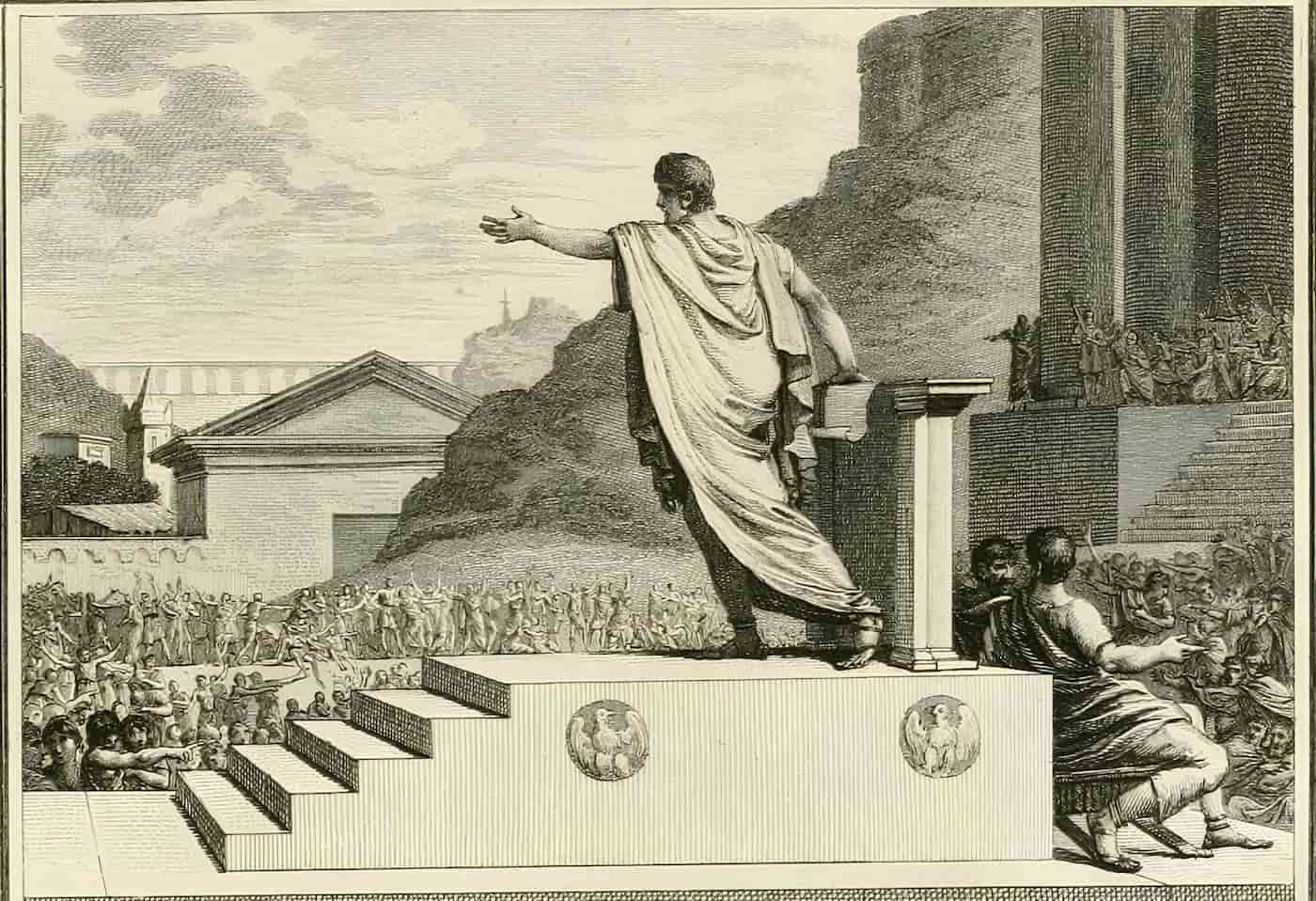

Even though he was just 14 years old, Elagabalus became the new Roman emperor. His grandmother, Julia Maesa, really wanted their family to rule the empire again after Caracalla was killed. Thanks to her clever moves and power, Elagabalus was made emperor in AD 218. Elagabalus was younger than most Roman emperors in Roman history.

Elagabalus’s journey to power and his time as emperor were unconventional, with some strange actions on his part and the involvement of notable individuals. One notable person who chronicled this period in Roman history was the historian Lucius Cassius Dio.

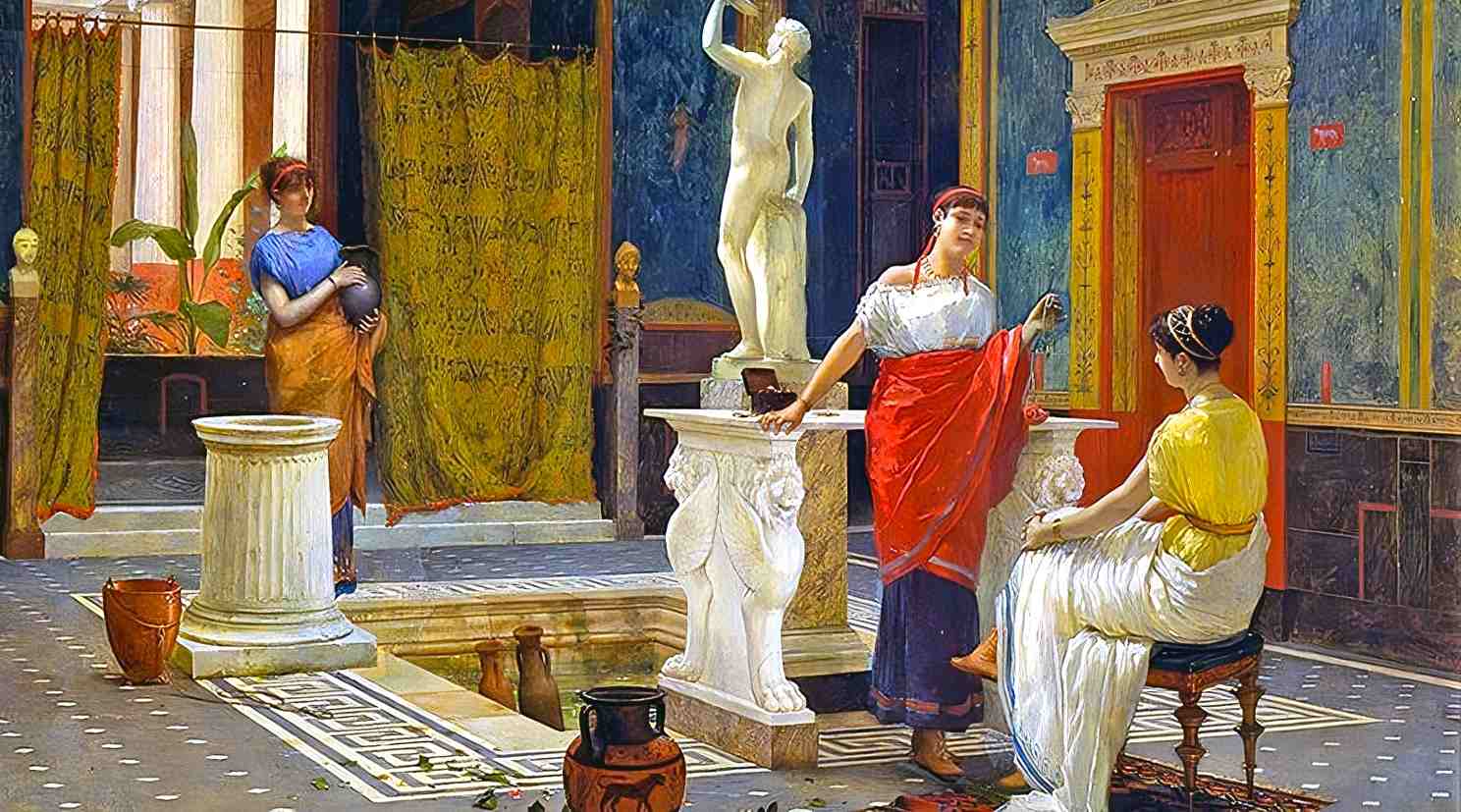

According to Cassius Dio, Elagabalus had some unusual habits. He liked to be called “Lady” and dressed in women’s clothes. He even promised a reward to any doctor who could make him physically become a woman. Dio also tells us about Elagabalus’s fancy parties, where he would cover his guests in flowers and perfume.

He went as far as having flower-filled chariots race through the city streets. Elagabalus’s marriages were quite unconventional too. Dio mentions that he even married a Vestal Virgin, which was a serious violation of Roman religious traditions and caused quite a scandal.

The Cult of Elagabal

Emperor Elagabalus introduced a significant religious transformation during his reign, centered around the deity Elagabal (Elagabalus, Aelagabalus, Heliogabalus), from whom he derived his name. This new religion was distinguished by novel customs. It represented a break with conventional Roman beliefs.

Elagabal, the sun god, was first worshipped in Emesa, which is now modern-day Homs, Syria. This is where Elagabalus’ family came from. The young emperor was really into the Elagabal cult and wanted to make this god more important in the Roman pantheon.

Religious Reforms and Controversies

Elagabalus made some changes to the religion in Rome. He built a new temple for Elagabal, a god he really liked, and in this temple, there was a special black stone that symbolized the god. This stone was brought from Emesa to Rome. Elagabalus wanted people to worship Elagabal more than the usual Roman gods like Jupiter.

The shift in religious beliefs created a ton of disagreements and pushbacks in Roman society. It impacted everyday people, the Senate, and even the military. Elagabalus made things worse by introducing foreign gods and customs while disregarding Roman traditions, leading to widespread unrest throughout the empire.

The Historia Augusta has some interesting stories. One of them is about Elagabalus, who’s said to have done some questionable stuff in the palace, like allegedly acting as a prostitute and marrying lots of people, including his chariot driver. He also liked exotic animals and would let them loose in the palace for entertainment.

Eccentric Reign and Controversies

An Extravagant Life

In the relatively short period of his reign, Elagabalus exhibited a clear preference for opulence and grandiose displays. He organized feasts characterized by the extravagant use of valuable resources and extravagant dishes. This was a bit concerning because the Roman Empire was having economic problems at that time.

Personal Life and Relationships

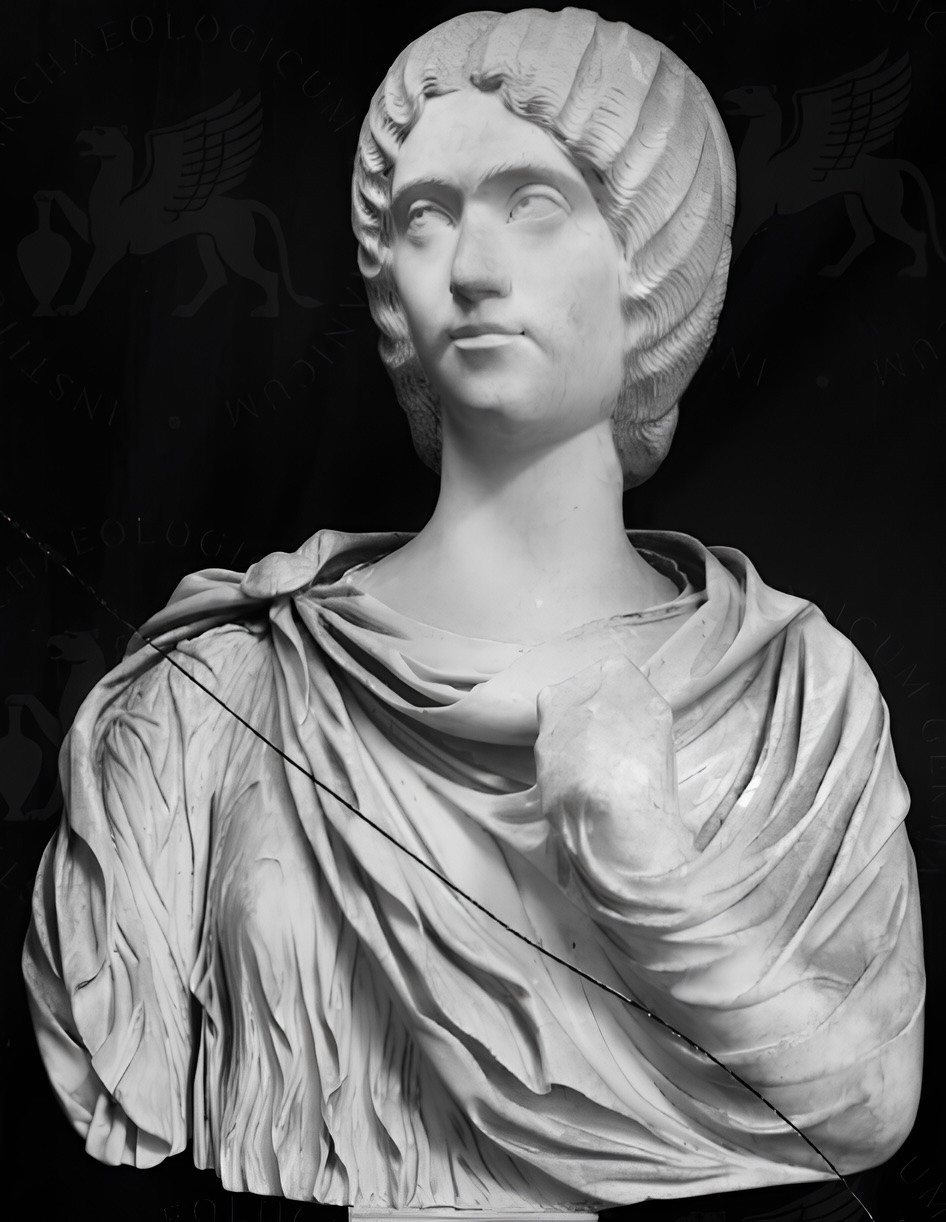

One of the most striking controversies during Elagabalus’s rule centered around his stance on gender. He openly expressed a preference to be recognized as a woman and even entered into a marriage with a man. This move greatly scandalized Roman societal conventions.

Elagabalus engaged in numerous marriages and divorces, often with little time in between. One of his best-known unions was with Aquilia Severa, who held the esteemed position of Vestal Virgin, a role of great religious significance in ancient Rome. This marriage was particularly scandalous because it went against the sacred commitment to chastity that Vestal Virgins were obligated to maintain.

Controversies and Opposition

Elagabalus’s unusual behavior and religious approach did not sit well with the Roman Senate which held significant political influence. Tensions between the emperor and the Senate escalated. This created political conflict.

The emperor’s neglect of Roman military customs upset the legions. His concentration on religion and his choice of personal pleasure over military matters made people worry about the empire’s stability.

Herodian’s account highlights Elagabalus’s extravagant banquets and parties. He discusses the influence of Elagabalus’s mother, Julia Maesa, and the Praetorian Guard on the emperor’s rule. Herodian generally portrays a moral decay during Elagabalus’s reign.

Governance and Challenges

Inexperienced Leadership

Elagabalus, who ascended to power at a young age, faced a significant challenge due to his limited experience in governance. Instead of focusing on ruling, he devoted resources to his religious pursuits. This diversion of funds occurred at a time when the Roman Empire was grappling with financial difficulties. The imperial treasury was already strained, and desperate measures, such as devaluing Roman currency, were taken in an attempt to bolster finances. These actions only exacerbated the empire’s financial problems.

Military Conflicts and Invasions

While Elagabalus was in charge, the Roman Empire had some problems with the Parthian Empire in the East. He didn’t pay much attention to the affairs of the army, which weakened Rome when dealing with these issues.

The Roman frontiers had to deal with attacks from different outsider groups, like Germanic tribes and other barbarians. The emperor’s struggle to deal with these border threats made the security situation even worse.

Decline and Removal from Power

Plot Against Elagabalus

Elagabalus’s rule became increasingly unpopular among different groups in Roman society. The Senate, the military, and the general population were all unhappy with his way of governing. Some Praetorian Guard members devised a plan to remove him from power in the year 222 AD.

A dramatic conspiracy unfolded against Elagabalus, resulting in a forceful overthrow. Elagabalus and his mother, Julia Soaemias, met their demise at the hands of the Praetorian Guard. Elagabalus’s rule had spanned merely a few years and ended when he was just 18 years old.

Legacy

Elagabalus had a brief rule, but it left a big mark on the Roman Empire. After him, Alexander Severus wanted to steer clear of the controversies during Elagabalus’s time and bring back order. Elagabalus’s reign was a lesson for later Roman emperors to remember to honor the old Roman ways and institutions.

After Elagabalus’s assassination, the Senate declared damnatio memoriae against him. This meant that they sought to erase his memory from the historical record as a form of censure for his actions and reign. Efforts were made to remove or deface inscriptions, statues, and references to Elagabalus. His images were also destroyed or altered. Despite these efforts, some information about Elagabalus’s reign and actions has survived through historical accounts.

Elagabalus at a Glance

What impact did Elagabalus’s reign have on the Roman Empire?

Elagabalus’ rule is commonly viewed as a time of confusion and declining moral standards. It made the Roman Senate less influential and added to the larger issues the Third Century faced. During this era, there were many different emperors coming and going, and the empire had to deal with various external threats.

Who succeeded Elagabalus as Roman Emperor?

Following the murder of Elagabalus in 222 AD, his cousin Alexander Severus took over as the Roman Emperor. Alexander Severus aimed to bring back order and the old Roman ways to the empire.

What is the significance of the Severan Dynasty in Roman history?

The Severan Dynasty, which lasted from 193 to 235 AD, was a Roman ruling family. They had emperors like Septimius Severus, Caracalla, and Elagabalus. During their rule, the Roman Empire went through big changes and problems, like wars, family fights for power, and economic issues.

What led to the downfall of Elagabalus as Emperor?

Elagabalus stirred up quite a bit of trouble because of his unusual religious beliefs and his complete disregard for the way things were done in ancient Rome. He lived a really lavish life and didn’t care much about what the Roman Senate had to say. In the end, he was assassinated when he was just 18, in a coup, and his cousin Alexander Severus took over as ruler.

References

- LacusCurtius • Cassius Dio’s Roman History (uchicago.edu)

- Herodian 5.3 – Livius

- Historia Augusta, The Life of Elagabalus Part 1

- Transcending Gender: Assimilation, Identity, and Roman Imperial Portraits on JSTOR

- Featured Image: The Roses of Heliogabalus by Lawrence Alma-Tadema (1888). Public Domain.