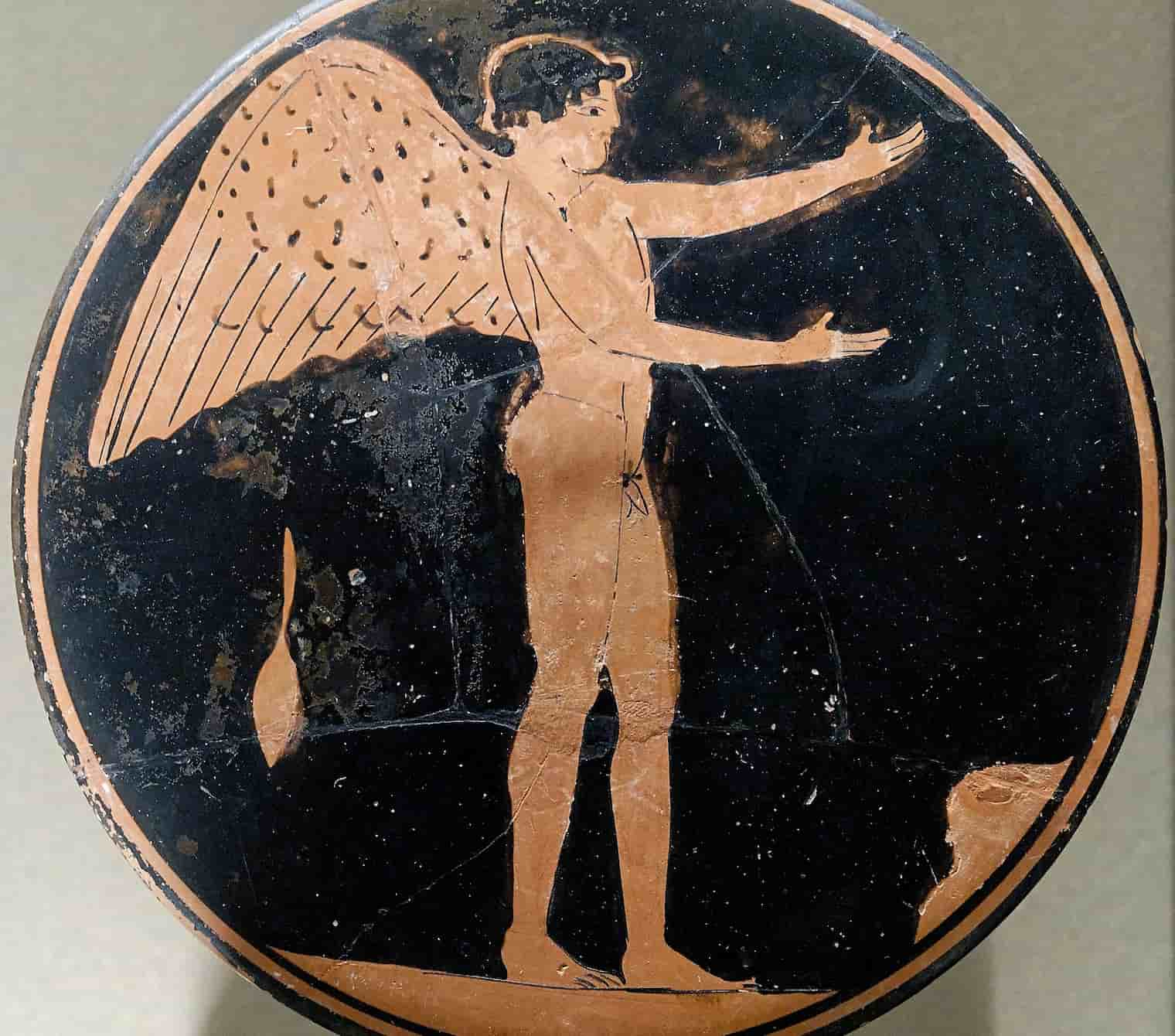

Taraxippus, or Taraxos in the Eliac version of the myth, is mentioned as the son of Peneus and Creusa, “the one of disturbance, noise, and fear.” Ovid, in support of his opinion that rivers experienced love on their own, provides examples of river love, including that of Peneus and Creusa. Peneus, through his marriage to Tethys, the daughter of Oceanus, gave birth to Anteros, “the one of understanding, logic, and courage.” The mythological interpretation of Anteros is that he is capable of standing against the invincible. The myth suggests that the two sons of Peneus fought for supremacy, and the battle took place within Peneus. With the help of Hermes, Anteros emerged as the victor. He founded the city of Antreia (Antrevida) and gifted it a horse.

Origin

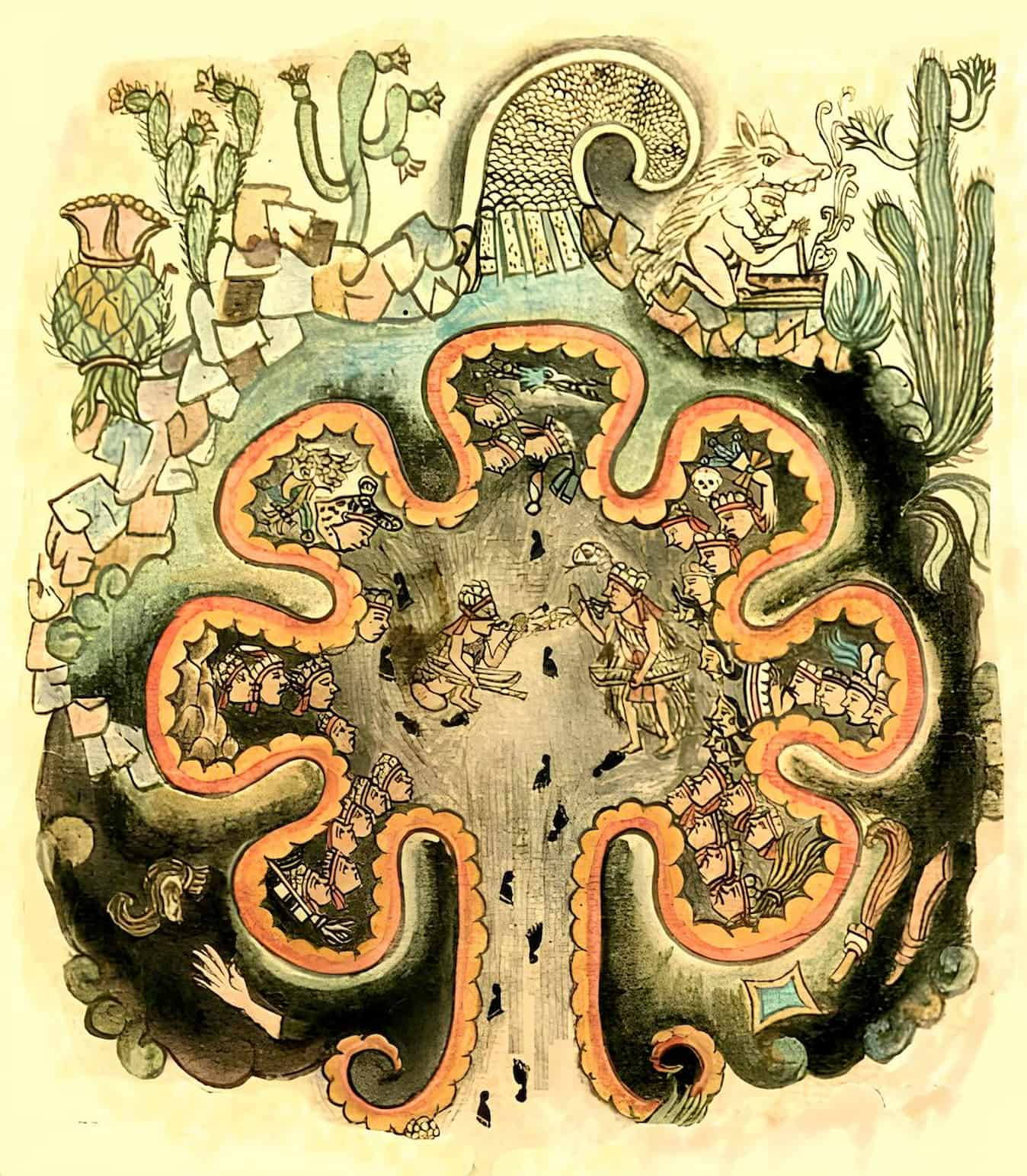

Taraxippus (plural: Taraxippoi), according to Greek mythology, was a daemon primarily located in Olympia and the Isthmus, lurking in the racecourses, especially in their turns, where chariots made maneuvers. The ancients believed that during the critical moment of the turn in the races, Taraxippus would suddenly appear. Although invisible to the charioteers, its appearance instilled terror in the horses, resulting in the collapse of the chariots and the destruction of the competitors. For this reason, the ancients erected altars from mounds at those points of the racecourses in honor of Taraxippus. The charioteers also performed special sacrifices to appease Taraxippus, seeking his favor. According to the traveler Pausanias, Taraxippus was considered an epithet and not a unified entity.

The most notorious among the demons bearing this name, as mentioned by Pausanias, is Taraxippus of Olympia.

In the horse race, one side is longer than the other, and on the longer side, which is an embankment, lies the terror of the horses, Taraxippus. It takes the form of a round altar, and when horses look at it, a strong and sudden fear grips them without apparent reason. This fear causes disturbance, leading to the destruction of chariots, and the charioteers are often injured.

buy ozempic online https://dcsmentalhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jpg/ozempic.html no prescription pharmacy

Therefore, the charioteers offer sacrifices and pray to Taraxippus to be favorable to them.buy wegovy online https://dcsmentalhealth.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/jpg/wegovy.html no prescription pharmacy

Mythology

According to mythology, Taraxippus was the spirit of the deceased Oinomaos, while in other versions, it was associated with Olenios or Dameon, the son of Phlios, who aided Heracles in the war against Augeias and the Epeians. He was killed along with his horses by Kteas, the son of Aktor. In different traditions, Taraxippus was linked to the worship of heroes or the god Poseidon, who, due to his role as the god of horses, caused the death of Hippolytus.

Taraxippus of Corinth

In ancient Olympia, Taraxippoi were considered the spirits of those unjustly killed in equestrian competitions and generally those who fell from horses. The same applied to the Isthmus of Corinth, where Taraxippus was considered the spirit of Glaucus, the son of Sisyphus, who had died in equestrian competitions.

Certainly, beneath the charm of Greek mythology, all these myths refer to the initial observation of the centrifugal force, where the construction of embankments (altars) at the turns of the racetracks and the attention of riders and charioteers on them ceased the chariots from exiting or colliding with each other. This knowledge is embodied in Taraxippus.

Taraxippus of Olympia

He would be the ghost of Myrtilus, son of Hermes and charioteer of Oenomaus. Pelops corrupted him, and Myrtilus sabotaged his master’s chariot to make him lose a race. After winning, instead of granting the promised reward, Pelops killed him. Overcome with remorse, Pelops decided to erect an altar in the name of Myrtilus in the Olympia hippodrome. Before each race, offerings were made, and charioteers offered prayers to him.

Other origins are mentioned by Pausanias: Olenius, who gave his name to the “Olenian stones,” or Damion, son of Philios, who went on an expedition with Heracles against Augeias, where he was killed by Cteatus. His body and his horse were buried in the same tomb. There is also mention of a certain Alcathoos, killed by Oenomaus because he courted Hippodamia and lost the race.

Taraxippus is also sometimes used as an epithet of Poseidon.

Instances

There were several myths associated with the artificial mound (or hill). It was either the tomb of Olenius, a local native and rider; or the tomb of Dameon, a companion of Heracles; or the cenotaph of Myrtilus; or the tomb of Oenomaus; or the tomb of Alcaeus (son of Porphyon); or some object received by Pelops from Amphion was buried here; or the name is connected with the epithet “Hippian” of Poseidon (the Horse). Lycophron considers Taraxipp to be the tomb of Ixion.

On the Isthmus’ hippodrome, there was its own Taraxipp, Glaukus – the son of Sisyphus, met his death by horses (mares tore him apart), during the legendary funeral games organized by the Argonaut Akastus in honor of his father Pelias.

In Nemea, in the Argolid region, there was no hero who harmed horses, but the rock rising at the very turn of the racecourse, red in color, shining like fire, instilled fear in horses: Taraxipp in Olympia is much more harmful and scares horses much more.