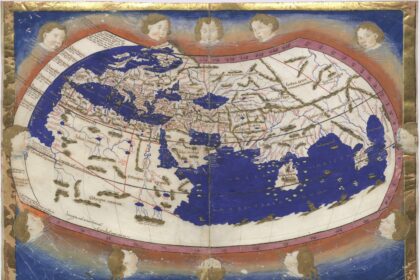

On February 6, 2023, the earth shook in Turkey. At 4:17 a.m. (local time), a magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck the area around Kahramanmaraş in the south of the country, followed nine hours later by another magnitude 7.6 earthquake. The human and material toll was catastrophic: 53,500 victims in Turkey and at least 5,950 in Syria, with more than 173,000 buildings partially or completely destroyed. The often dramatic consequences of earthquakes are evident near their epicenter, but they can extend far beyond through mechanisms that remain poorly understood. Zaur Bayramov, from the Institute of Earth and Environment in Strasbourg, and his colleagues traced the effects of the Kahramanmaraş earthquakes all the way to the Kura Basin in Azerbaijan, over 1,000 kilometers away.

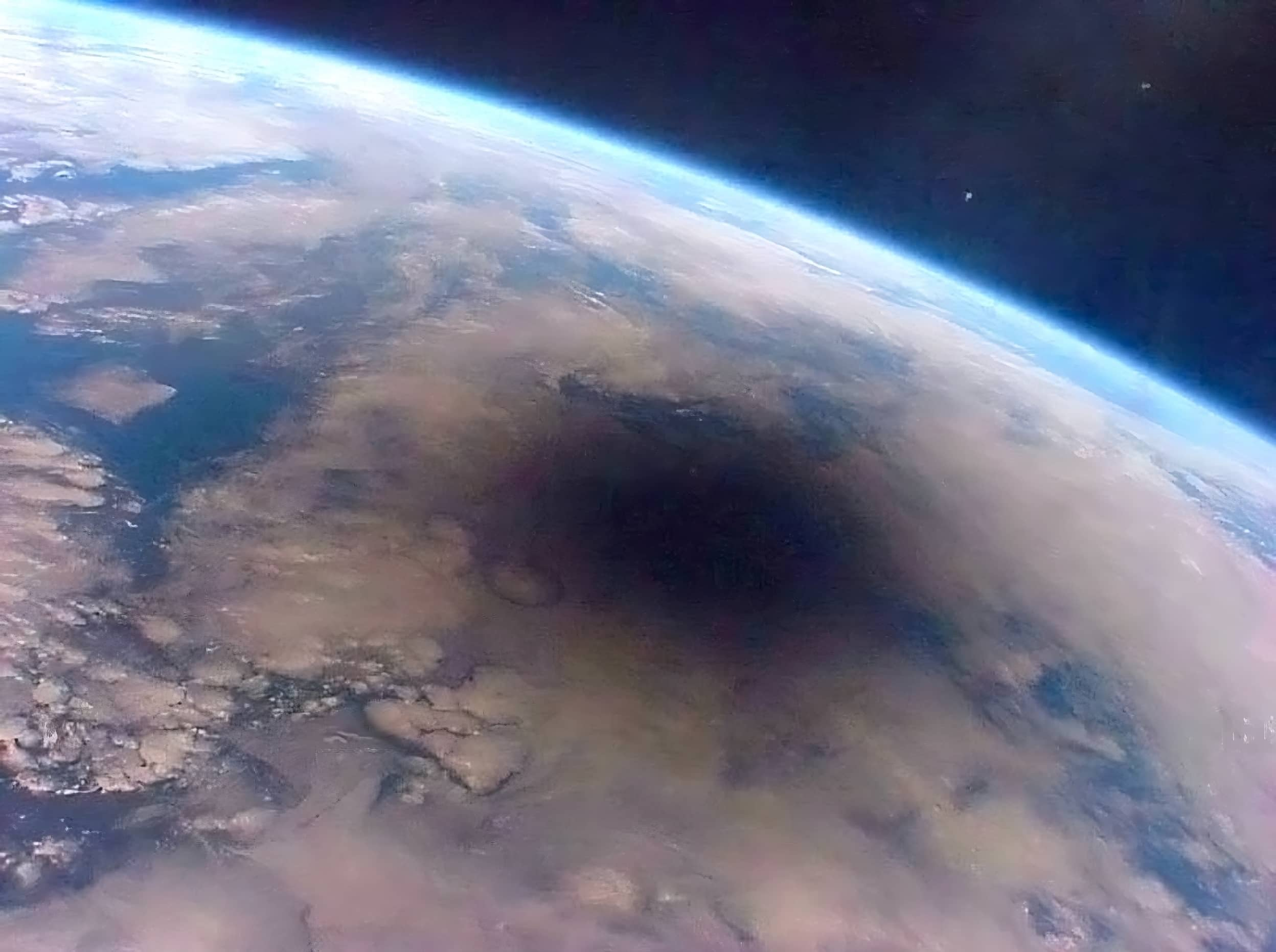

These two earthquakes came as no surprise. They are linked to the particularly intense tectonic activity in this region, at the boundary of the Anatolian and Arabian plates—a vast area under close monitoring. Using satellite imagery, the researchers reconstructed displacement maps of the fluid-saturated Kura sedimentary basin at the beginning of 2023. They observed slips of several centimeters along multiple faults at the time of the earthquakes in Turkey, but not before or after.

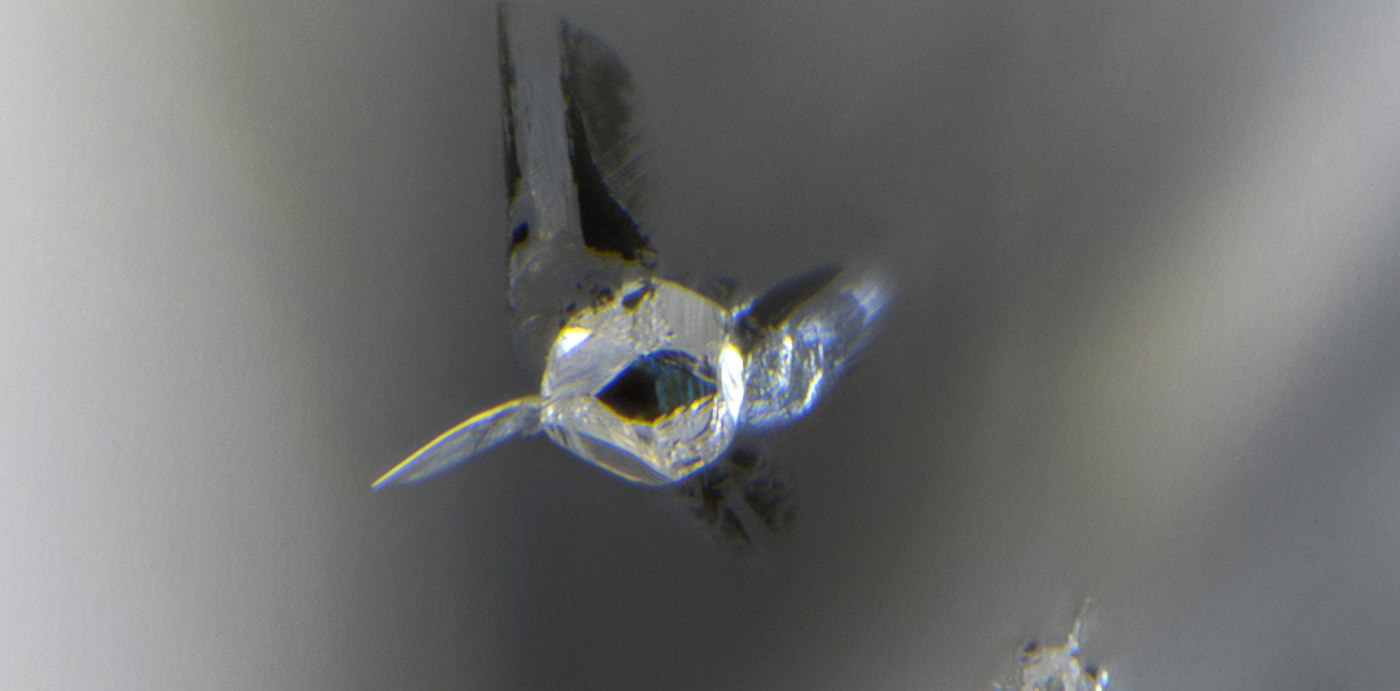

Remarkably, these strike-slip tectonics (horizontal sliding) were aseismic, meaning they generated no seismic waves and therefore no tremors, even though their amplitude corresponded to what would normally be observed during a magnitude 6.1 earthquake. Additionally, 56 mud volcanoes in the region erupted at the time of the earthquakes (whereas on average only about ten awaken each year). Mud volcanoes function similarly to other volcanoes: their eruptions are caused by fluid overpressure beneath the volcanic structure. Furthermore, 22 other mud volcanoes deformed, and an area of the basin rich in hydrocarbons and near a moving fault temporarily rose.

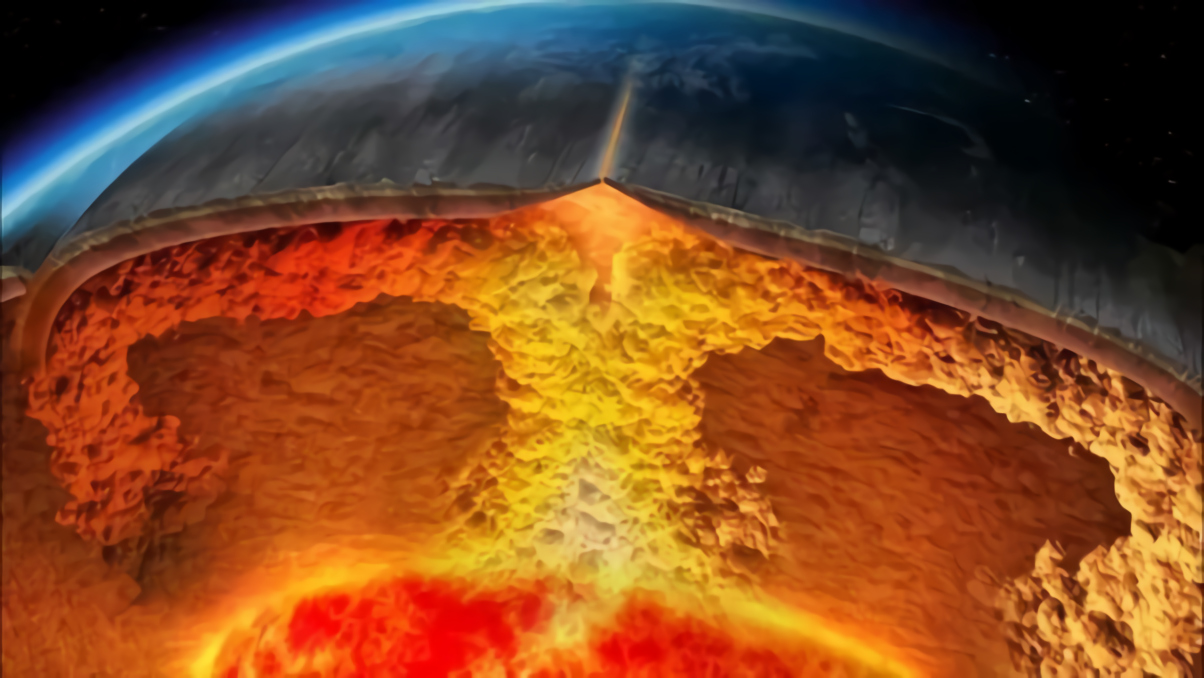

The simultaneity of the earthquakes and these various events led Zaur Bayramov and his colleagues to propose the following scenario: the arrival of seismic waves from Turkey caused an increase in the pressure of fluids contained in the basin (water, oil, gas), which in turn caused the eruption and deformation of mud volcanoes, the uplift of part of the basin, and the slipping of faults. Through this mechanism, the velocity of movement along the faults was lower than that along faults directly linked to an earthquake, and therefore too slow to trigger seismic waves (known as a “slow” or “silent” earthquake).

These results provide evidence of the involvement of fluids in triggering silent earthquakes by distant geological events, a phenomenon previously suspected but never before observed. According to the researchers, it is crucial to take these mechanisms into account, for example in assessing seismic risks in the Kura Basin.