On the eve of what historiography has termed the “Age of Discovery,” the Christian West held a geographical worldview that blended Greek, religious, and empirical influences, tinged with a sense of mystery. This perspective was far removed from the transformative understanding of the world that would emerge from the explorations and conquests of the 16th and 17th centuries, which decisively altered how the world was perceived and ushered in modernity. The first explorers, such as Christopher Columbus, were still men of the Middle Ages.

“T-O” Mappa Mundi

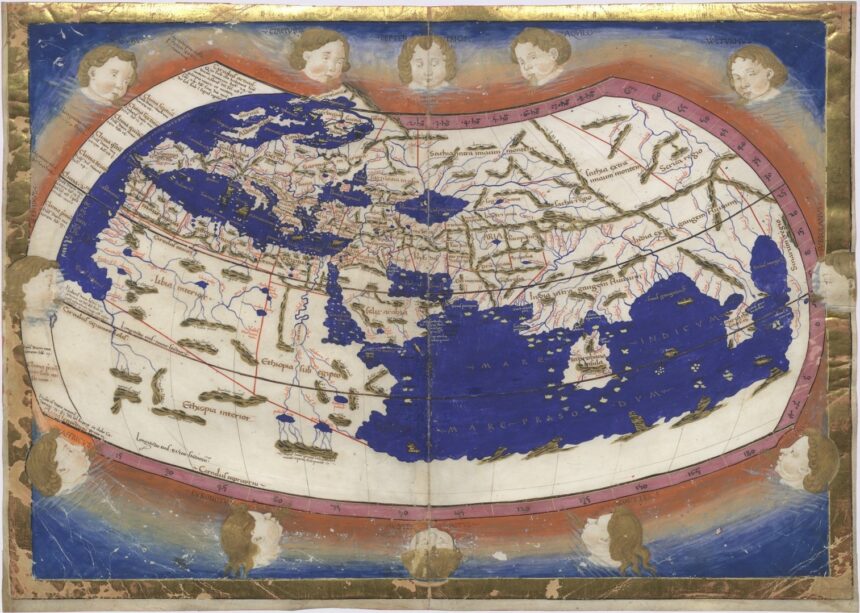

The “T-O” mappa mundi model is the primary representation of religious influence on medieval geography. Drawing inspiration from ancient scholars and biblical narratives, Church Fathers like Isidore of Seville (560-636) divided the world among the three sons of Noah: Asia to Shem, Europe to Japheth, and Africa to Ham.

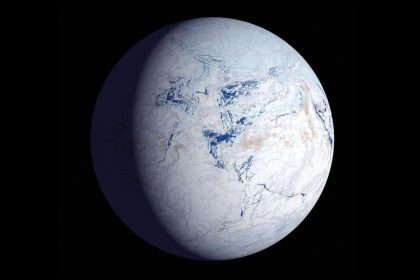

This geographical vision depicted the Earth as flat, contributing to the misconception that medieval people were unaware of the planet’s roundness (despite this knowledge dating back to antiquity and being studied by medieval scholars familiar with Greek science). The East was placed at the top, symbolizing Eden, the Paradise.

The “T-O” model persisted until the end of the Middle Ages, with the three sons of Noah occasionally being replaced by the Three Magi, each symbolizing a “continent,” even though the term “continent” itself is more characteristic of the modern era.

The Role of Portolan Charts

Marine charts, which developed significantly from the 13th century onward, were crucial in understanding how Europeans viewed the world at the time. Originating from Italian thalassocracies (Pisa, Genoa, Venice), portolan charts were used for Mediterranean navigation as early as the 13th century. These charts, often drawn on parchment, featured coastlines, ports, and hazards, and incorporated the use of the compass.

A network of lines drawn on the sea allowed navigators to reach ports marked on the chart.

Initially created for practical navigation and based on precise observations, portolan charts quickly became collector’s items, often idealized representations that blended cartographic details with figurative iconography, displayed in studiolos and princely palaces. They were richly decorated with geometric and floral motifs, coats of arms, ships, animals, and other designs.

These charts essentially served as catalogs of ports, with names labeled in red or black according to their importance, but without indicating distances between them. Major rivers and sometimes topographical features were schematically represented, without accurate proportions.

The World Map Before 1492

The influence of Greek thought was central to the geographical understanding of the world. By the 15th century, the vision of Ptolemy, a 2nd-century Greek geographer, had become the most popular, gradually supplanting the flat, religious worldview of earlier centuries with the concept of a spherical Earth, as proposed by Eratosthenes. According to Ptolemy, the Indian Ocean was enclosed, a feature reflected in 15th-century maps, such as that of Nicolaus Germanus (1482).

In 1450, the monk Fra Mauro created a mappa mundi that synthesized various cartographic traditions, both Christian and Arab, incorporating empirical information from early explorations of the time. While influenced by Ptolemy, Fra Mauro rejected the idea of an enclosed Indian Ocean.

However, the most striking example of the 15th-century worldview, bridging the Middle Ages and the modern era, is undoubtedly the Behaim Globe. Inspired by Ptolemy, it integrated information from the travels of Marco Polo and John Mandeville, whose accounts would later guide Christopher Columbus himself.

The Behaim Globe depicted a narrowed Atlantic Ocean, which, if crossed, would lead directly to Cipango (Japan) and Asia. In the middle, it was missing just the New World, which would be “discovered” a few months later by the Genoese navigator…