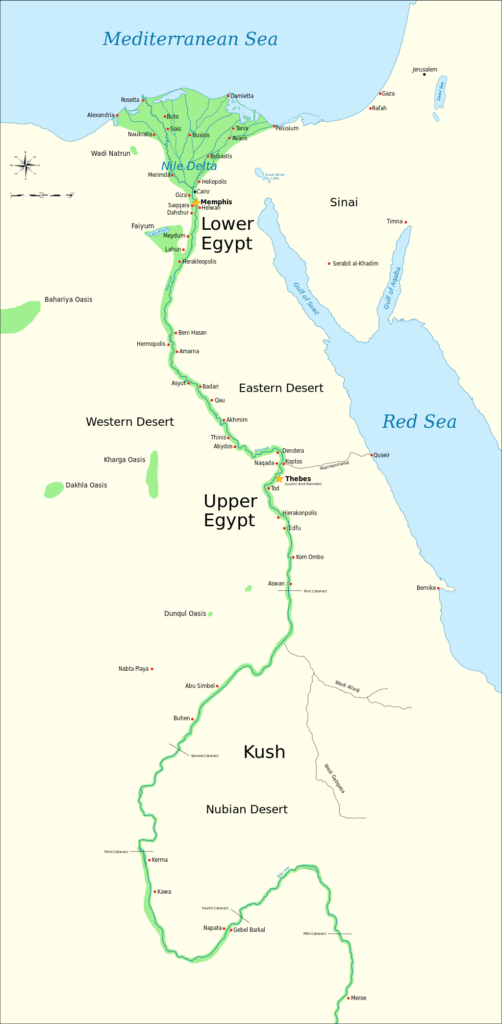

The Unification of Upper and Lower Egypt refers to the emergence or reunification of the Pharaonic central state. The history of Ancient Egypt knows three such events: the initial formation of the state in the predynastic period, attributed to the first Pharaoh Menes, the reunification by Mentuhotep II during the civil war at the end of the First Intermediate Period, and the reconquest of Lower Egypt by Pharaoh Ahmose at the end of the Second Intermediate Period.

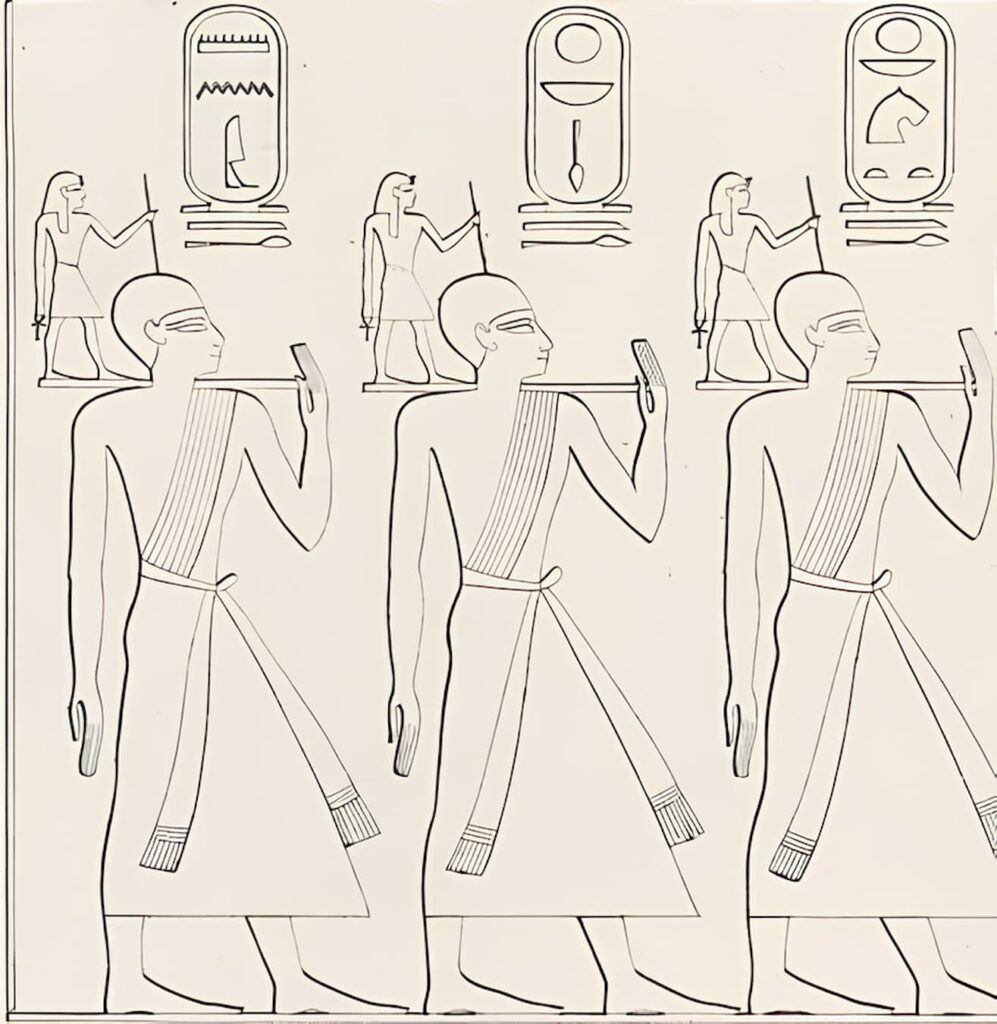

Iconography

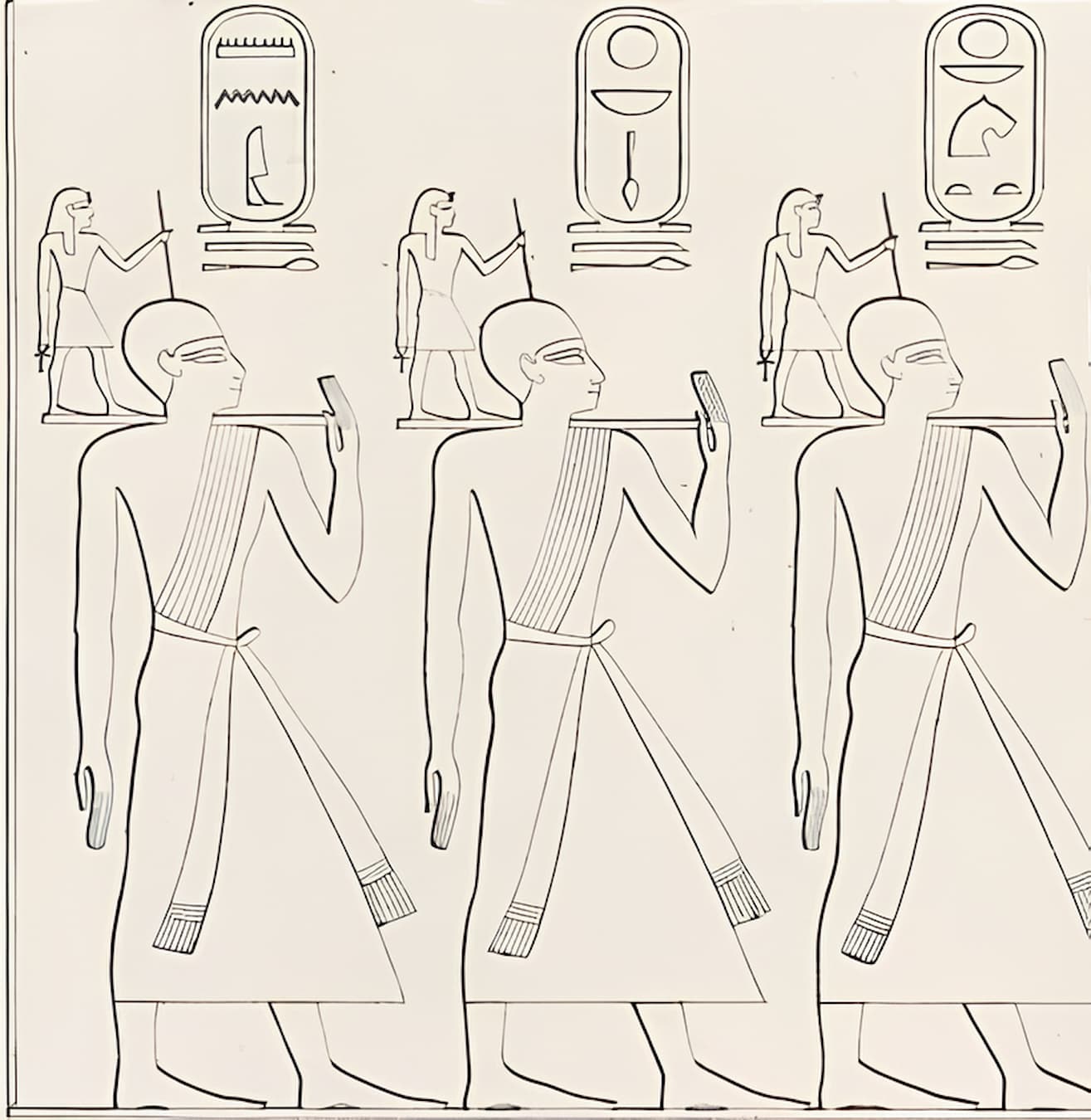

Iconographically, the union is represented by the symbolic plants of Upper and Lower Egypt, the lotus and the papyrus, which are either wrapped around the trachea or artery of an animal by Horus and Seth or by two Hapi figures. Other symbols of the union are the bee and the bulrush, as well as the gods Wadjet and Nechbet in the royal titulary.

Pharaoh

Very few records survive from this period, so very little is really known about unification, but we do know that it happened sometime at the beginning of the third millennium BC, when the king of Upper Egypt invaded and occupied Lower Egypt.

The unified ruler of the two kingdoms bore the title of pharaoh. From a religious point of view, it is important that all of Egypt worshiped Pharaohas a falcon-God Incarnation of Horus. Thus, the title of pharaoh could have been held by a unified ruler over the two countries, and Menes is known to have been the first pharaoh in Egypt, but according to other sources, the name of the first pharaoh is Narmer. Many scientists believe that these two names mean the same person.

Narmer

There is debate among historians about who the unifying warrior king was. There is an argument that the second king of the First Dynasty is Hor-Aha. Others claim that only the last king of the Second Dynasty is Hasehemui, since the empire was not really united, it only became so during his reign, but this is contradicted by the fact that even before him, a king was depicted wearing the unified crown.

According to the Narmer palette, it is clear that Narmer, the first king of the First Dynasty (3150 BC – 2613 BC), already wore the unified crown, so it is generally accepted that the unification took place during his reign.

First Unification

The first unification of Upper and Lower Egypt is mostly attributed to Menes, who ruled as king around 2980 BC. However, the assessment as the “first unifier of the empire” is unhistorical, as his predecessors already understood themselves as rulers of Upper and Lower Egypt within the framework of the unification festival. The designations of Shemu for “Upper Egypt” and Mehu for “Lower Egypt” were first attested under King Iri in the predynastic period.

Period

Regarding the first unification of the two parts of the country, Upper and Lower Egypt, reference is often made to the time of Menes and Narmer, although it is not yet certain whether Menes is Narmer or Aha. The main source for this is the Narmer Palette, with some Egyptologists interpreting the iconographic motif of “striking the enemy” in Lower Egypt and attributing Narmer as the “conqueror of the enemy” in Upper Egypt. However, it remains unclear whether Narmer achieved a victory over all of Lower Egypt or only over some regions. It is also not certain whether Menes was the first unifier or whether similar unions occurred before. Furthermore, the exact boundaries at that time were disputed, making it impossible to precisely assign the former parts of the country.

For example, Wolfgang Helck refers to archaeological finds in connection with the Horus processions, suggesting that documented exchange deliveries speak to the existence of a centrally governed Egypt even before Narmer. Vessel inscriptions and clay engravings from Girga, Tarchan, and Abydos are among the earliest evidences of trade exchange. Whether these exchanges were trade relations or served as the basis for rituals cannot be determined due to the lack of textual sources. Most of these vessel inscriptions are made of black ink and were subsequently burned. Jochem Kahl also sees the exchanged objects closely linked to the Horus processions as symbolic gifts from the king, associated with ceremonies rewarding high dignitaries. Two picture tablets found in Naqada suggest a connection with festival activities during this ceremony. Thus, the king appeared in front of his palace on the so-called Menes tablet to inspect the deliveries made.

As a rationale for earlier assumptions of Menes as the “first unifier of the empire,” Wolfgang Helck cites the first appearance of documented annals. Additionally, the field of Egyptology has debated whether the unification was achieved peacefully or violently and whether there was even “one unification” at all. The contents of ancient Egyptian sources, pointing to a longer period during which numerous unifications took place, argue against a single act of unification. Thus, there was no central, singular unification. Rather, the merging of both parts of the country took place over several centuries and stages until the Middle Kingdom, marked by intermittent separations.

Execution of the Unifications

Recent research shows that the unifications were not accomplished through military conquests, although occasional military conflicts occurred. For example, the previously often assumed connection between the total number of captives under Narmer in connection with a military conflict can no longer be maintained. An army size of more than 100,000 individuals cannot be evidenced in the Old Kingdom, so Narmer probably counted all inhabitants of a region and then referred to them as “rebels” (“sbj.w”) through the determinative; furthermore, there was no differentiation between men and women. Thus, “Narmer Macehead” describes the overall peaceful takeover of a larger region, simultaneously possessing the character of a census.

In the early phase of the unifications, the number of counted “rebels” in relation to the concurrently mentioned livestock proved notable. Mostly, this ratio during the Predynastic and Old Kingdom periods was about 1:3; in the New Kingdom, it increased to 1:10. The recorded figures under Sneferu represent one of the few exceptions. Usually, the listed tribute payments from regions outside the actual core territory serve as the basis for the mentioned figures. The change in the ratio suggests that in the early phase of unification, larger areas gradually became part of the actual dominion. Additionally, a change in lifestyle as a result of sedentarization is seen as a complementary possibility in this context.

Second Unification of Egypt

After the death of the last pharaoh of the 6th Dynasty, Pepi II, the Old Kingdom collapsed in the First Intermediate Period along its regional borders into a multitude of regional states. After a century-long civil war, the Theban king Mentuhotep II succeeded in his 14th year of reign in conquering the competing regional state around Heracleopolis and restoring the unity of Egypt in the Middle Kingdom.

Third Unification of Egypt

As a result of the invasions by the Hyksos and Kushites, Pharaonic rule in the Second Intermediate Period was pushed back to a third of its previous territory. Over time, the kings residing in Thebes reconquered the land, with Ahmose I, the founder of the 18th Dynasty, achieving the final expulsion of the Hyksos and the restoration of Egyptian great power status.