Like a skilled sculptor, evolution shapes living beings over time, allowing them to better adapt to their environment. This enables living species to conquer all available habitats, even those that appear most hostile to us. Few terrestrial environments are as inhospitable as deserts, whether hot or cold: water and food are scarce, temperature variations are extreme, and dangers abound.

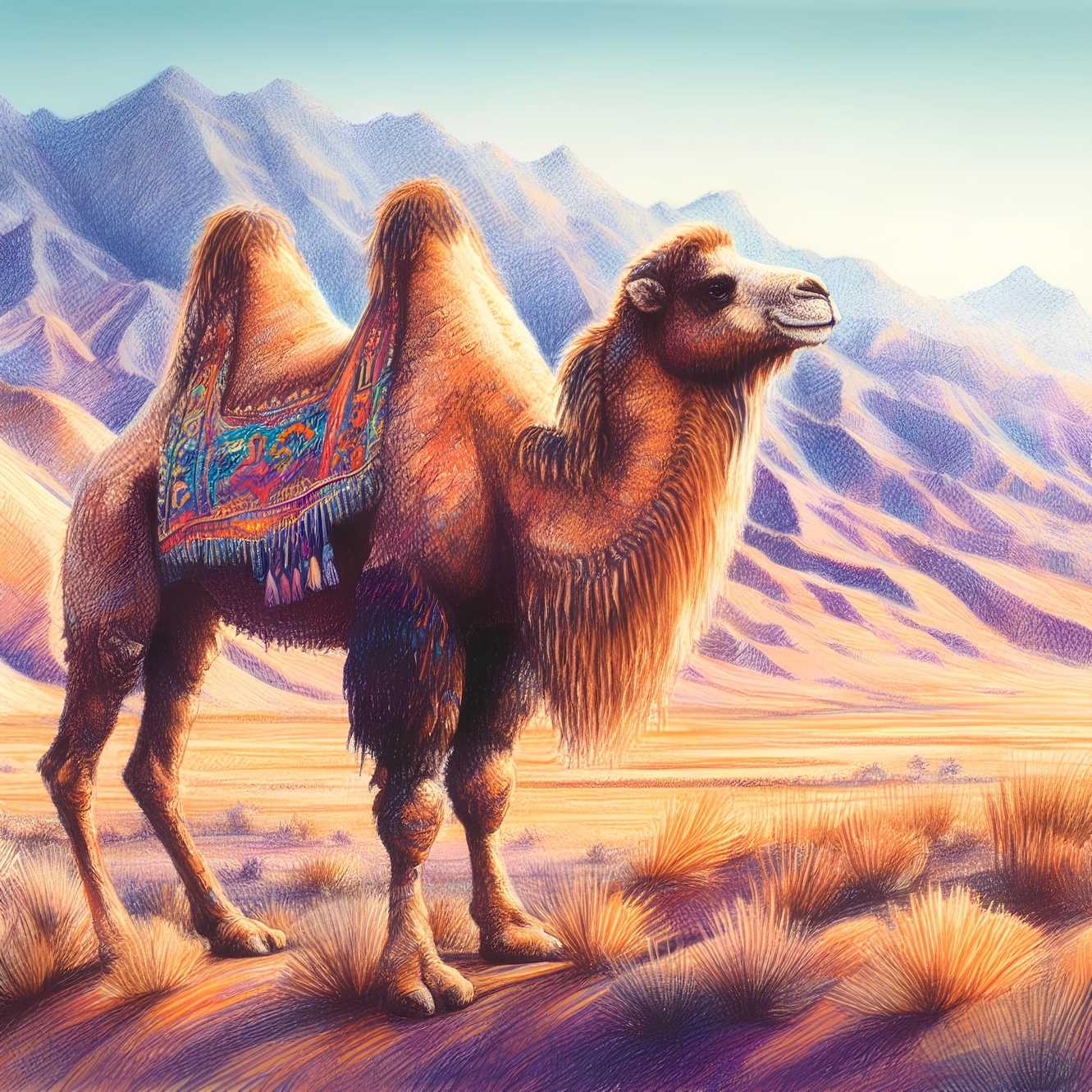

Yet a few animal species make these arid places their home, among them the Bactrian camel.

It’s in the Gobi Desert, Mongolia, that we find the last population of wild Bactrian camels. Covering nearly 1,300,000 square kilometers, one of the world’s largest deserts is known for its significant temperature variations, from 38°C (100°F) during the hottest summer days to -40°C (-40°F) on the coldest winter nights.

In just 24 hours, temperatures can vary by 35 degrees, so the animals living there must demonstrate great endurance and be well adapted to this challenging environment.

Just like its close cousin, the dromedary, the camel is built to withstand the extreme conditions imposed by its environment.

Its light-insulating fur acts as a thermal shield, protecting its skin from direct exposure to the scorching sun in the summer. Thickening in winter, it insulates the animal from the biting cold during freezing nights. The camel can also endure a variation in body temperature from 34°C (93°F) to 41°C (106°F) without any impact on its health. In comparison, a human can barely tolerate an internal temperature variation of over 1°C without showing symptoms (fever, hypothermia).

Extremely Useful Humps

One of the most striking features of the camel is undoubtedly the presence of two humps on its back. Here again, we discover a clever adaptation to help the animal cope with the challenges of its environment.

No, the humps do not contain water! They are, in fact, reserves of fat that the camel uses when deprived of food for extended periods; each hump can weigh up to 23 kilograms (50 pounds).

The metabolic conversion of this fat provides twice as many proteins and carbohydrates as any other energy source. Moreover, for every gram of fat converted, a gram of metabolic water is produced. The secret of its extraordinary adaptability to its harsh environment lies in its water-saving capability.

Bactrian camels and dromedary camels are different species. Bactrian camels have two humps, while dromedary camels have one. Their geographic ranges also differ, with Bactrian camels primarily found in Central Asia and dromedary camels in the Middle East and North Africa.

Saving Water to Survive

The animal can go without water for extended periods without suffering from the effects of dehydration. In fact, it can lose up to 30% of its body weight in water without any consequences. In humans, a loss greater than 12% can be fatal for most people.

Nevertheless, the camel minimizes its water loss to the maximum, never knowing when its next drink will come. Its droppings are very dry, and its urine is highly concentrated compared to other mammals of similar size; it can be twice as salty as seawater.

Additionally, although the animal has sweat glands, it rarely sweats except in extremely hot conditions, allowing it to minimize water loss through evaporation. Its coat insulates its skin from direct heat and reduces the use of this strategy to lower the mammal’s internal temperature.

Remarkably well-adapted, sooner or later, the camel still needs to drink water. Faced with a water source, the animal drinks to its heart’s content, consuming up to a hundred liters in one go.

Domesticated for over 4,500 years, the Bactrian camel has enabled human populations living in some of the most inhospitable places on the planet to obtain food, engage in trade, and travel between isolated communities.

While there are millions of domesticated camels, the wild population now numbers only about a thousand individuals. The camels of the Gobi Desert, devoted companions in a life of extreme conditions, now have more to fear from human activity than from their environment if they are to survive extinction.