The large wig worn by Louis XIV was a way for him to show his power and authority. The wig, which was originally made of natural hair instead of fake hair, was a symbol of the Bourbon monarchy until the French Revolution and was worn by people belonging to a certain social class. The wig remained popular for 150 years and the barbers who made them were considered skilled craftsmen during the reign of the “Sun King.” However, the wig eventually fell out of use in the 19th century.

The Wig: From Antiquity to the Beginning of the Grand Siècle

The practice of wearing wigs, which was popular during the reign of Louis XIII, can be traced back to ancient civilizations like Greece and Rome. Xenophon wrote that young warriors in Sparta kept their hair long to appear bigger, more noble and more terrifying. Throughout history, long hair has been associated with strength and authority, and cutting off someone’s hair was a way to symbolically degrade them. This was especially popular in the Merovingian dynasty. However, in the 6th century, Gregory of Tours prohibited Christian women from using non-Christian hair to create tower-like tall hairstyles.

During the reign of Louis XIII, the popular hairstyle was short hair. However, the king preferred long hair, so some members of the court and nobility added extra hair to their own to achieve the desired length. To style their hair according to the fashion of the time, people would part their hair at the top of their heads and comb it down on both sides, extending it below their ears and creating a “floating” tail at the back of their heads. As the tail grew longer, people used other people’s hair to maintain the look they desired.

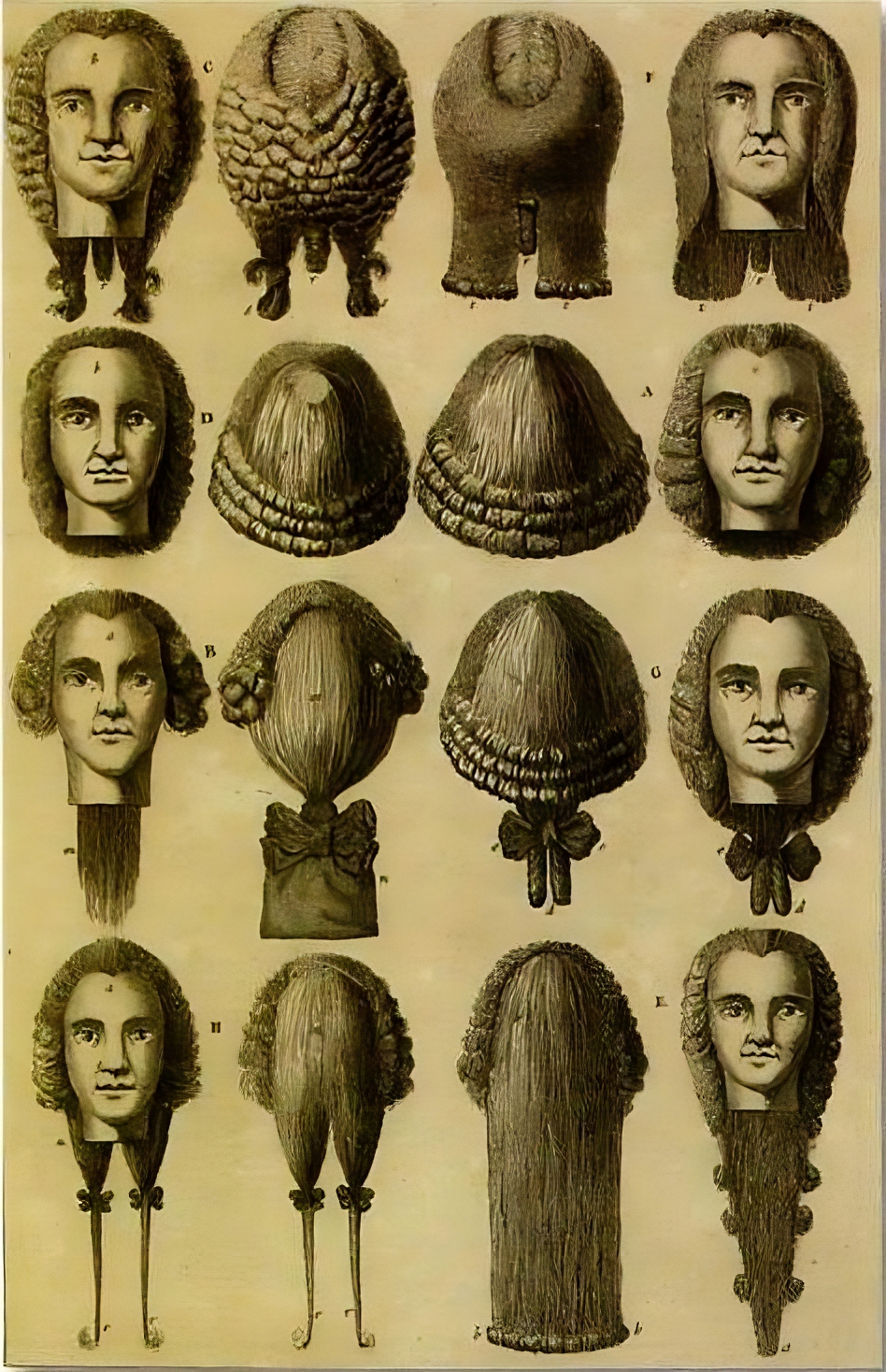

At the age of 30, Louis XIII started to lose his long hair and began wearing wigs, which were also known as “false wigs.” In 1634, the king authorized the creation of 48 wigmaking positions in the capital. There were two types of wigs: caps, where the hair was individually passed through a sheepskin sewn onto a small cap, and “moutonnes,” which were for bald people who couldn’t afford a cap. The hair was braided between three and five silk strands, which were then sewn onto assembled ribbons and placed on wooden heads to shape the wig.

The Wigs of Louis XIV

During Louis XIII’s reign, wigs became extremely popular and were an essential accessory. No public appearances were made without a royal wig, which was long, curly, and curled, falling to the shoulders. The wig played a crucial role in representing a person’s character and was seen as “the symbol of the sun king” demonstrating the greatness, power, and magnificence of the king of France.

Initially, even though Louis XIV had plenty of hair, the king wore “towers,” which were wedges applied to the sides and back of the head to create a thicker appearance. Around 1673, Louis XIV started using wigs with windows that had strands of real hair passing through them. Later, he adopted full wigs.

Since the fashion was to imitate the king, everyone from young boys to courtiers to members of the nobility wore wigs. The middle class also embraced the trend, and lawyers, prosecutors, and doctors all wore wigs when visiting the palace or their patients. The clergy was the only group that resisted, holding onto the Council of Constantinople’s ruling from 1,000 years earlier. It wasn’t until 1660 that the abbot of La Rivière dared to wear a wig, and young canons followed his example.

The Wigmakers of the Sun King

Louis XIV’s servants were divided into various professions, including the King’s Chamber, which was responsible for the personal care of the monarch. Among the 60 people under the First Gentleman of the Chamber, ordinary barbers and valets de chambre-barbiers were tasked with combing the king’s hair, both in the morning and at bedtime, and wiping it off in the baths. These trusted craftsmen were chosen by the king and were devoted to his personal care, with some even becoming confidants and receiving patents.

Their salary is about 750 livres per year, but with the gratifications obtained, their income rises considerably from 30,000 to 60,000 livres (the value of an ordinary barber’s office).

The morning routine of the king was a formal ceremony, and the first item he put on was a wig. The valet presented him with a selection of wigs to choose from based on his planned activities for the day. After his hair was combed and he was shaved, Louis XIV would wear a short wig for everyday use. Louis XIV wore a long wig for council meetings and ceremonies.

Over time, the wigs became larger and more elaborate. They started out as blond with curls falling on the shoulders and back, but eventually changed to brown and black, extending down to the waist. When Miss de Fontanges joined Louis XIV’s entourage in 1690, wigs became shorter and were styled with a curly toupee that was five to six inches high and formed two points. Near the end of his reign, Louis XIV adopted a lighter, ashy or white wig that was powdered and perfumed with Cyprus powder (a mixture of oak and flour with a strong scent) to soften his appearance.

These large, powdered wigs weighed three to four pounds and were worth 1,000 livres tournois, which is equivalent to around €23 in 2023.

Design and Conservation of a Royal Wig

The production of a single royal wig required the hair of 50 women, which had to be collected from living donors who were preferably from rural areas (where women didn’t use bonnets to hide their hair) and had hair that was between 24 and 25 inches in length. Male hair was not suitable for use in these wigs because it was too dry and brittle.

The wigmaker obtained the raw hair from the Flanders region, the region of beer, which was known for producing high-quality hair. The finished wigs were kept in a special storage room called the Cabinet des Perruques or Cabinet des Termes in the King’s Apartment. The cabinet was located near Louis XIV’s bedroom and contained the king’s golden wig, which was created for a performance in February 1662 at the Tuileries. The cabinet ceased to exist in 1755, after the royal family moved to the Palace of Versailles.

The Disadvantages of the Wig

While wigs were carefully maintained by barbers, they were often filled with dust and vermin. However, even if Louis XIV gained 30 cm in height, he had to endure many inconveniences: the weight and compression on the skull caused headaches, glare, dizziness, and even itchy skin.

Additionally, trying on wigs in drafty castles caused Louis XIV to frequently catch colds. In 1696, the constant wearing and rubbing of a wig resulted in the development of a boil that turned into a large carbuncle on the back of the neck. Ten years later, another anthrax appeared in the same place and had to be treated in the same way.

As a result, wigs gradually became shorter and were styled differently, such as with a tail tied at the back, with hair enclosed in a small bag, or in Spanish style.

The Incomparable Artists

The Binet and Quentin families were both responsible for providing barber services at the Court. The Binet family, specifically Georges Binet, was well-known for creating wigs, including a famous golden wig for the Tuileries show. Binet was appointed as the ordinary barber in 1684 and went on to create the “binettes,” large royal wigs. After Binet’s death in 1695, his son took over until 1716 when he stepped down.

Quentin was known for operating a bathhouse in Paris that was frequented by Louis XIV and other young courtiers. He became famous for offering “Polville’s powder,” a substance that increased energy and was popular with lovers. In 1669, he gained a position with the queen, and in 1671 he received a patent for four positions as a valet de chambre-barbier, which allowed him to serve the king on a full-time basis. Quentin was eventually ennobled in 1681, becoming the marquis of Champcenetz in 1686, and a gentleman of the chamber in 1702. He passed away in 1710.

His younger brother became the king’s wigmaker and created the window wig in 1673. He worked to improve this fashion accessory by styling it in various ways. The king also granted him the privilege of making industrial wigs that were copied and exported. In 1674, the brother became the king’s coat rack, and in 1697, he became the “valet of the garderobe”. He served as the maître d’hôtel of the King’s Household from 1704 to 1716, and was later ennobled in 1693 and given the title Baron de Champlost in 1721.

These skilled craftsmen were able to live comfortable lives, thanks to the royal favor they received for their talent and increasing fame in Europe. They were also able to retire from their duties at court shortly after the death of the king, showing respect for the monarch.