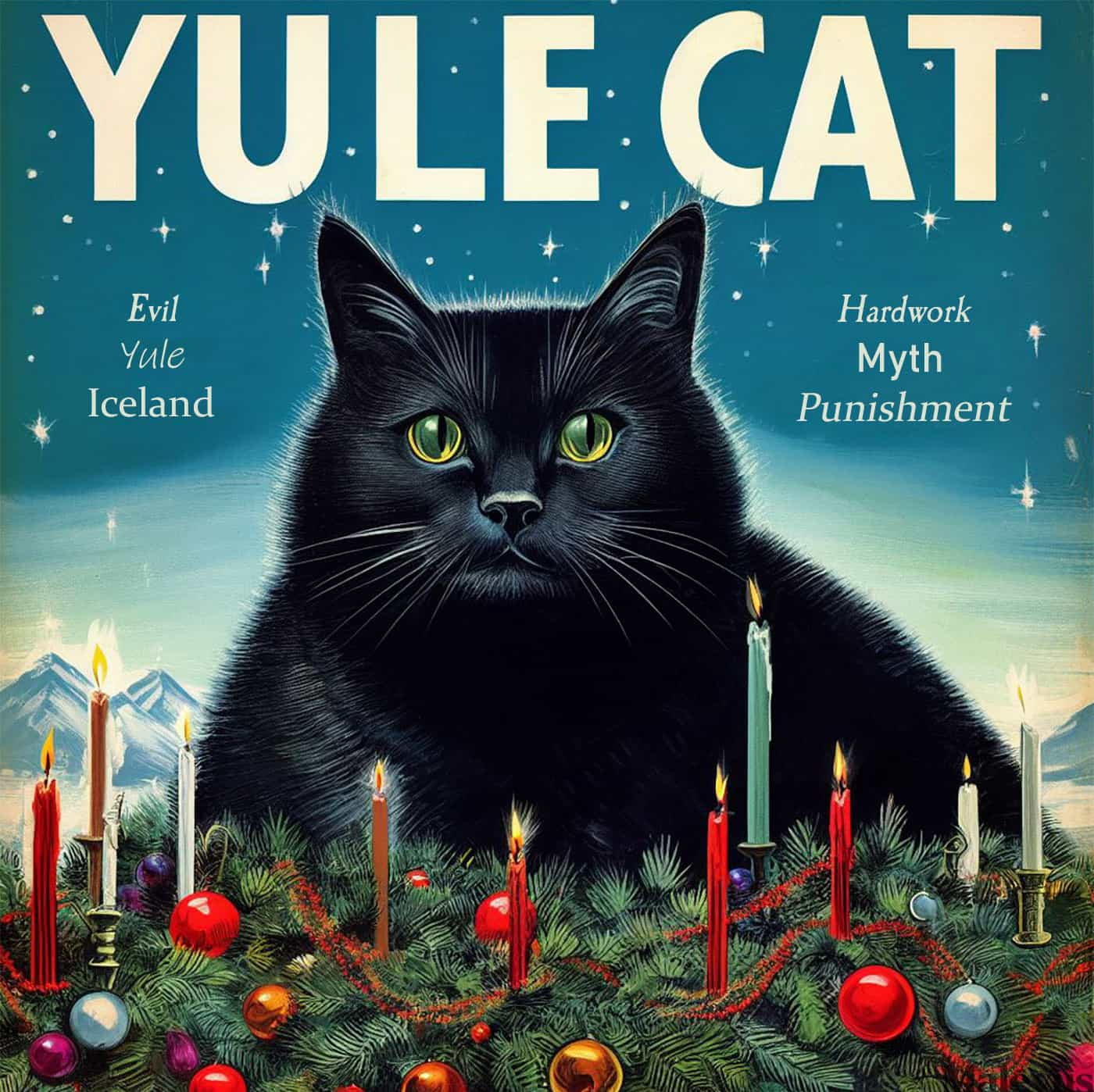

In Icelandic mythology, there is an unwanted creature called Yule Cat, also known as Jólakötturinn, that lives in the highlands of Iceland and is a black cat monster the size of a bull. The story of this terrifying mountain cat was first documented in the nineteenth century. In Icelandic tradition, the male Yule Cat is said to share a cave with the witch Grýla, a giantess-cannibal who abducts youngsters who are rebellious and naughty; Leppalúði, her husband, who is a total slob who never gets out of bed; and their kids, the thirteen Yule Lads, who are equivalents of “Santa Clauses” in the homeland.

The Story of the Yule Cat

Those who haven’t gotten at least one woolen item for the winter festival Yule are attacked and devoured by the traveling Yule Cat that visits cities and villages at Christmas. For instance, in order to save the children from the chore of the cat, who did not receive new clothes for Yule, the tale goes that they were given candles along with a few clothes, socks, or shoes. In that sense, the story also instructs people to help the less fortunate by giving them gifts.

In some tellings of the story, the Yule Cat doesn’t devour the kids but their Yule food; in other tellings, its target also includes the grownups. In another variant, the Yule Cat makes its way down from the mountaintops during the holiday season and roams the snowy countryside, but he is only limited to capturing those who are short on Yule goodies. It is claimed that those who fail to replace their old clothes in Iceland have “gone to the Yule Cat” (Icelandic: hann fór í jólaköttinn), which means that they have brought themselves misfortune.

Even though the Yule Cat has been around for a long time, the first recorded references to this Christmas cat didn’t appear until the nineteenth century. Farmers in Iceland would use the Yule Cat as a threat to get their staff to complete processing the wool they had received in the fall before Yule (around Dec 21–Jan 2).

Those who helped out the effort were rewarded with new clothing, while those who did not receive nothing and, thus, became prey to the dreadful Yule Cat. In the third alteration, the cat is seen eating the food from the Yule dinner of individuals who do not have new clothes.

The poetry of the Icelandic author Jóhannes úr Kötlum (1899–1972) and other traditions contributed to the widespread belief that the Yule Cat devours humans. The second volume of Icelandic folklorist Jón Árnason’s Icelandic Folk Tales and Adventures states the following about this mythical cat:

However, people could not enjoy the joy of Yule completely carefree because, in addition to the Yule Lads, it was believed that there was an unexpected person on the move called a Yule cat. He didn’t really hurt anyone who got some new clothes to wear on the Eve of Yule, but the others who didn’t get any new clothes were said to have “gone to the Yule Cat,” so he took them or at least their Yule gifts and it was considered fortunate if the cat was pleased with what he took.

Árnason’s famous Yule Cat poem reads:

You all know the Yule Cat

And that Cat was huge indeed.

People didn’t know where he came from

Or where he went.He opened his glaring eyes wide,

The two of them glowing bright.

It took a really brave man

To look straight into them.

Origin of the Yule Cat

Because of Iceland’s relative isolation from the rest of the world ever since its founding, most of Icelandic folklore is original and depicts the harsh realities of life. The Yule Cat may have trollish roots, as Scandinavian folklore mentions witches summoning a ‘troll cat’ for magical purposes. Shamanic traditions also involve taking on a feline form. A recorded story from Norway tells of a Finn transforming into a large black cat to steal a silver spoon as a token.

The precise beginnings of the legendary image of the Yule Cat are linked to shepherding in Iceland, where sheep breeding was an important part of every family. “Vaðmál” (Wadmal), the coarse wool made from sheep’s fleece, was a business run by families.

Processing the wool was a family affair that included everyone from small children to elderly relatives after the sheep shearing during the months of fall. Working in tandem with the Icelandic market season, this task usually comes to a close right before Yule (Jól), which is around December 20–22.

Houses with the ability to spin wool were in great demand, yet there were years when it was difficult or impossible to work wool because of things like poverty, conflict, starvation, or death. Icelandic families still got together in the hopes that the Christmas Cat would not prey on any of their loved ones.

Domestic winter wear, particularly for older children, was fashioned from handloom material, and it was customary to knit little things, such as gloves and socks for everyone from the family. Those who worked hard leading up to Yule got new things, while others who were careless and hadn’t made anything by the time the markets opened were left behind. People used to scare their kids with the Yule Cat to get them to work harder.

Is the Yule Cat Actually the Yule Goat?

One theory suggests that at the origin of the Yule Cat lies the Yule Goat, which is a Scandinavian and Northern European symbol with a Pagan origin. The Norse deity Thor was associated with the Yule Goat because he traveled through the sky in a chariot pulled by two goats.

It is possible that the Yule Goat first traveled to Iceland from Norway around the 18th century, but the character transformed into a cat during the introduction since goats are so rare in Iceland. A similar phenomenon is found across the Eastern Baltic, where it takes the form of a cow.

According to Swedish folklore, the Yule Goat is a spirit that appears just before Christmas to check if everything is in order with the Yule festivities. This tradition is similar to the behavior of the Yule Cat.

On the other hand, Grýla’s origin may be traced back to the Middle Ages, specifically around 13th-century Norse mythology. Her tradition, which is similar to the Italian Befana figure, became intertwined with the Yule Lads by the 17th century. The lineage of these young lads is said to originate from East Iceland and extends back to ancient times.

However, the Icelandic government later outlawed the practice of passing on terrifying tales of the Yule Lads to youngsters in 1746. These days, they’re just playful, harmless creatures. The Yule Cat has come to be associated with the giantess Grýla and her Yule Lads (Jólasveinar) since the 19th century. This cat is also said to belong to an ancient tradition, but written evidence has only been found in modern times.

Why a Cat and Not a Dog?

Iceland has always been a cat country, where cats have been more common than dogs. Hence, the country even banned dogs in 1924 after the increased cases of fatal tapeworms passed onto humans from dogs.

The goddess of love and magic, Freya, was said to have ridden a chariot drawn by two enormous flying cats that looked like the Norwegian forest cat in Icelandic mythology. The giant and woolly appearance of the Yule Cat might be explained by this, since Icelandic mythology places a high value on cats.

-> See also: The Black Cat Myth

Figures Similar to the Yule Cat

Although not exactly identical, there are other Christmas figures from other nations with similar purposes of creation:

- Krampus: A half-goat, half-demon creature, Krampus is also a disciplinary character during the Christmas season. He appears in the mythology of Central Europe. He is the polar opposite of Saint Nicholas. The fear of Krampus serves as a deterrent to misbehavior among youngsters, much like the Yule Cat.

- Frau Perchta: In German and Austrian tradition, there is a witch named Frau Perchta who, during the course of the Christmas season, bestows a notoriously horrific punishment on the wicked: having their inside organs torn out and replaced with trash.

- Hans Trapp: Hans Trapp warns misbehaving children to be good or face abduction to the dark forest using his scarecrow disguise.

- Belsnickel: Belsnickel taps windows, jingles bells loudly, and accuses children of misdeeds.

- Père Fouettard: Père Fouettard, French for ‘Father Whipper,’ dispenses lumps of coal and beatings to naughty children.

In Popular Culture

The Yule Cat is still a prominent Yule figure in today’s Icelandic folklore, where certain monuments and dedications are made to the cat every holiday in the country. There are many pieces of art that focus on it, and the animal has become a more common sight in Icelandic holiday décor in recent years.

In the above image, you can see a large cat figure dedicated to the animal in the Icelandic capital Reykjavík, with the title “Christmas Cat.” The City of Reykjavík spent 4.4 million ISK ($31,400) on this large LED cat.

The worldwide famous Icelandic singer Björk released a song named “Jólakötturinn” in 1987 and the lyrics are inspired by Kötlum’s poem.