Where Did the Idea That America Exists Come From?

Europeans did not immediately realize that the lands across the Atlantic, where they found themselves, were not Asia, but a new, unknown part of the world. However, this does not mean that by the time Columbus’s expedition was planned, Europeans had no concept of lands lying west of Europe, in the “Sea of Darkness.” On 13th to 15th-century maps, various islands were marked—some well-known, others mythical, like the Island of Saint Brendan, Antillia, and Brazil. The belief in their existence influenced Columbus’s decision to venture across the open ocean. But these were thought to be islands; it was only some time after Columbus returned from his first voyage that people began to talk about a new part of the world beyond the ocean.

- Where Did the Idea That America Exists Come From?

- Who Discovered America and When?

- Were North and South America Discovered at Different Times?

- What Were the First Colonists Like?

- What Did They Eat and How Did They Survive?

- Where Did Native Americans Come From — Have They Always Been in America or Did They Arrive from Somewhere Else?

- How Many Were There, How Did Different Tribes Live, and What Do We Know About Them?

- How Did the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples Occur and Why?

- How Did Mexico, the USA, and Canada Come to Be?

- What is the Oldest City in America?

- How the Discovery of America Affected the European Economy

- How Did It Change European Culture?

- And the Food?

Columbus himself likely believed until his death that he had not discovered a new part of the world, but rather a new route to the countries of the East. During his last voyage (1502–1504), he sincerely believed that the distance from where he was (near the Isthmus of Panama) to the Ganges in India was only two weeks. But not everyone agreed with him. In 1499–1500, Spanish and Portuguese sailors like Alonso de Ojeda, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, Pedro Álvares Cabral, and others discovered a continuous line of the eastern coast of South America—from the Isthmus of Panama almost to the Tropic of Capricorn. It was becoming increasingly clear that this land was not Asia, as it was known that all of Asia lay in the Northern Hemisphere.

The first to declare the discovery of a new part of the world was the Italian Amerigo Vespucci (1454–1512), who participated in Spanish and Portuguese expeditions to the coasts of South America. Vespucci personally traced thousands of kilometers of the coastline. In 1503–1504, he described his voyages in two letters that gained enormous popularity and were reprinted many times. In these letters, he emphasized that he was speaking of a previously unknown part of the world—a “New World.”

Vespucci may have only voiced the idea of a new part of the world; others may have surmised it earlier. For instance, such an idea could have easily occurred to the sailor and cartographer Juan de la Cosa, who participated in several voyages to the Americas. In 1500, by royal commission, he created a map that reflected the latest Spanish and Portuguese discoveries. This map aimed to define the boundaries of these countries’ territories under the Treaty of Tordesillas. It was the first to accurately depict the Greater and Lesser Antilles and a significant part of the western coastline of South, Central, and North America—contradicting contemporary understandings of Asia’s eastern coastline. De la Cosa likely realized this represented the outlines of a previously unknown part of the world, resonating with Vespucci’s letters. Thus, the idea that America existed—or more accurately, that newly discovered lands were a new, previously unknown part of the world—emerged around 1500–1503.

In 1507, the cartographer Martin Waldseemüller from Lorraine suggested in his book “Introduction to Cosmography” that the new continent be named “America” in Vespucci’s honor. The name “America” first appeared on Waldseemüller’s map that same year, located in the southern part of South America. Gradually, it became established on maps of North America as well. Neither Vespucci nor Waldseemüller intended to deprive Columbus of his laurels as the discoverer. Initially, it was understood that Columbus and Vespucci had discovered lands in different locations and that the name “America” referred only to the lands Vespucci had discovered. It was later applied to the entire continent discovered by Columbus—without Vespucci’s knowledge and against Waldseemüller’s wishes.

Who Discovered America and When?

Often, discovery is attributed to the first European visit to new lands, denying that status to those who arrived earlier, such as people from Asia who came to America via the Bering Strait. However, the situation with Europeans is not straightforward either. It is known that around the 10th–11th centuries, Vikings sailed to America, establishing settlements in Newfoundland and Greenland. However, they did not perceive the discovery of America as fundamentally different from discovering Iceland or the Faroe Islands.

It did not have a significant impact on either the Native Americans or the Vikings themselves. Moreover, this information, apparently, did not extend beyond the Scandinavian world and was forgotten by the end of the 15th century. For historians, unlike geographers, what matters is not so much the first visitation to a territory, but the establishment of contacts—regular and significant for both parties—between the “discoverers” and the “discovered.”

The discovery made by Columbus on October 12, 1492, quickly became a sensation across Europe, igniting a race for discoveries along the American coastlines. In the decade following Columbus’s return from his first voyage, at least twelve expeditions were undertaken by Spain, Portugal, and England. This event profoundly altered European life within a few decades. Thus, Columbus made the “true” discovery of America. However, he merely initiated the lengthy process of discovering and exploring various parts of America, involving hundreds of expeditions from many European countries.

Were North and South America Discovered at Different Times?

Yes, but there are nuances. First, the geographical distinction: unlike America as a continent, North and South America are separate landmasses, and Columbus’s discovery began with the Bahamas in the Caribbean, which does not belong to either North or South America. If we talk about the discovery of mainland territory, North America was discovered slightly earlier: an English expedition led by John Cabot, with his son Sebastian, seeking a northwest passage to the East, reached North America’s northeast coast in late May or early summer of 1498. During his third voyage, Columbus reached the mouth of the Orinoco River and discovered South America only in early August of that year.

Second, we cannot be certain that modern researchers know about all the voyages of that time. It is possible (though unlikely) that information, even indirect, might emerge regarding the discovery of the mainland parts of North or South America before the summer of 1498. For example, there are theories that the Portuguese knew about Brazil even before Columbus’s first voyage and that is why they insisted on moving the demarcation line further west during the Treaty of Tordesillas negotiations. However, there is no documentary evidence to support this.

What Were the First Colonists Like?

To better understand what the first colonists were like, it is important to consider, first, the differences between colonists from different countries. For example, settlers from Spain were quite different from the Portuguese, and even more so from the English or the French. Secondly, one must consider the conditions and circumstances they encountered in various parts of the New World. Emigration to Spanish and Portuguese colonies was strictly controlled by the authorities. For instance, for most of the three-century colonial period, one could only depart from Seville to the New World from Spain, and each colonist had to obtain an individual permit, with their name entered into a special list. However, it was very difficult to organize such control, and occasionally it was circumvented. The authorities were also very careful to ensure that only Catholics and subjects of the Spanish monarchs were allowed to settle in the colonies. Attempts by colonists from other countries to establish settlements in territories considered Spanish met with strong resistance.

Once rumors of the riches of America were confirmed by the successes of the conquistadors in Mexico and Peru, the flow of settlers increased. Until about the mid-16th century, most of the emigrants were potential conquistadors—those who relied on their swords rather than on the plow (although farmers and artisans were also among the first colonists). Most of them were poor natives of the southwestern regions of Spain, Extremadura and Andalusia, who were migrating not out of prosperity. They were characterized by energy and persistence—others simply could not survive there. At the same time, their pragmatism was astonishingly combined with a naïve belief in miracles: they were convinced of the existence of giants and Amazons, golden cities, and a fountain of youth in the vastness of America.

Few were lucky enough to participate in one of the few truly successful expeditions that enriched all survivors (such as the people of Francisco Pizarro, who captured the Sapa Inca Atahualpa and received a fantastic ransom for him). Even fewer among them were those who returned to Spain and lived luxuriously in palaces built from the captured treasures. The rest either quickly squandered their share or failed to amass a fortune and depended on the favors of the central government, including the grant of lands that were transferred along with the indigenous people living on them, known as encomiendas. Formally, the owners of encomiendas (encomenderos) were supposed to care for them, but in practice, they lived off the labor of the local population.

Around the mid-16th century, when the Conquista was coming to an end, the richest silver deposits were discovered in the territory of present-day Mexico and Bolivia. From then on, their exploitation became the main goal of the Spanish crown, and agricultural development of the conquered lands receded into the background for a long time. It was at this time that the main characteristics of Spanish colonization and the Spanish colonist were finally formed: he lives near enormous riches and is significantly involved in their exploitation—organizing it, ensuring its protection, and what we would now call infrastructure; he is very dependent on the metropolis, under its constant control; survival is generally not an issue for him, and he is not always willing to earn a living through his own labor. This was also influenced by the widespread view in 16th-century Spain that manual labor was an unworthy and even despised occupation.

Portuguese colonists were also seeking quick enrichment, but unlike the Spaniards, they did not find such deposits of silver in their territories. Later, they discovered gold and diamonds, but this occurred only at the end of the 17th and the first third of the 18th century. In the 16th century, their sources of wealth were the harvesting of valuable redwood, which was in demand in Europe, and the organization of the still technically imperfect but already profitable production of sugar from cane brought to Brazil from the Canary Islands. The idea that manual labor was ignoble also manifested itself here: the workforce in the artisanal industries, called engenhos, were dependent indigenous people and African slaves. The beginning of the mass importation of African slaves to Brazil is connected precisely with the expansion of plantation agriculture and sugar cane production, while the owners were referred to as “senhores” or “lords” of the engenhos.

If the Spanish and Portuguese territories were an integral part of the Iberian monarchies and were all in the same legal standing relative to the metropolis, the British colonies were different from the very beginning. There were three types of colonies. Royal colonies belonged directly to the crown and were governed by officials appointed from London. In corporate colonies, the crown (or the parliament in 1649–1660) endowed a special joint-stock company with the right to govern. In proprietary colonies, these rights were given to a particular individual.

Joint-stock companies or private individuals who received rights from the authorities to develop North American lands often concealed their real intentions on paper. For example, the Massachusetts Bay Company was founded in 1628. Its goal was to create an ideal world of Christian life in the New World in a Protestant-Calvinist interpretation (Calvinists in England were called Puritans)—a “City upon a Hill” from the Sermon on the Mount, as John Winthrop (1588–1649), the founder of Massachusetts, told the settlers before the ship departed. Six New England states in the northeastern United States emerged from Puritan colonization. The Pennsylvania colony was founded by William Penn (1644–1718) primarily for fellow Quakers, although the colony’s fundamental laws, drafted by him, stated that all settlers who believed in a single God were welcome in the new lands.

The royal colonies were mainly populated by the poor who hoped for a better life and their own land allotment in the New World. Most of them could not pay for the trip themselves and then worked off this “loan” for 4–7 years. Therefore, they were called indentured servants. Upon completion, they received land, sometimes with agricultural tools for its cultivation. Of the roughly 75,000 people who moved to Virginia and Maryland between 1630 and 1680, two-thirds arrived as indentured servants.

The first British settlers in North America found themselves in a completely different position compared to the Spaniards in Central and South America. Firstly, there was no gold, silver, or other wealth that attracted people with the temptation of easy profit. Although theoretical justifications for colonization soon appeared, emphasizing that the English could earn as much in these places from fishing and logging as the Spaniards did from gold and silver.

Secondly, the natural and climatic conditions were harsh for Europeans, and aid from the metropolis was minimal. Survival was only possible through daily hard work and strict discipline. In the very first permanent colony (Jamestown, Virginia), founded in 1607, only a few dozen of the 150 colonists survived the winter and spring of 1608, and such numbers were not uncommon.

Thirdly, relations with the Native Americans were different, and the Native Americans themselves were different. There were no highly developed civilizations here that had accumulated reserves of precious metals, as in Mexico or Peru, and there was nothing for the Europeans to take from the Native Americans except land. In the early years, contacts between colonists and Native Americans varied: from frequent bloody clashes (in the spring of 1622, Algonquin Indians killed 347 colonists—at least a quarter of Virginia’s population) to mutual assistance.

For example, in New Plymouth in New England, the Wampanoag Indians helped the colonists survive the first winter, and in gratitude, the colonists celebrated the first harvest together with the Native Americans. This is how Thanksgiving Day came about. At the same time, the density of the Native American population in the territory of the United States and Canada was much lower than in the Aztec or Inca states, and the Native Americans quickly retreated from the coastal areas where the colonists settled.

The first British colonists were generally hardworking and persistent, decisive, and able to stand up for themselves, deeply religious, and intolerant of religious dissent. Necessity taught them discipline. Compared to settlers from the Iberian countries, they were relatively less dependent on the metropolis and were used to relying on their own strength in everything.

What Did They Eat and How Did They Survive?

Hunger was a common companion for nearly all early settlers, especially in the first years. The colonists anticipated rapid wealth accumulation and support from their mother countries; plowing the land and raising livestock were often not part of their plans. Moreover, native food could be perceived as unworthy or weakening for the body. The settlers faced the dual challenge of a lack of familiar foods and an abundance of unknown ones. The diet was significantly different: while Europeans were accustomed to meat and dairy products, the indigenous people of South America (despite the variety of climate zones and economic systems in the region) relied primarily on plant-based foods, with protein coming not only from wild game and fish but also from insects. Furthermore, dairy products were unknown to the Indigenous peoples.

Another major difference in attitudes toward food was the consumption of raw, uncooked foods. For those from the Old World, this was seen as savage and barbaric; they believed that only animals ate raw food. In addition to this, a major psychological barrier for Europeans was the absence in the New World of two crucial crops: wheat and grapevines. Since Christian worship required wheat bread and wine, local substitutes (such as corn, manioc, and fermented beverages made from them) were considered inadequate replacements.

Initial attempts to practice European-style agriculture in the New World encountered serious difficulties: different levels of humidity and sunlight, different soil chemistry, a lack of natural pollinators, and opposite seasons in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres. There was also a shortage of labor: as mentioned earlier, Spanish and Portuguese colonists brought with them the notion that manual labor was not a noble activity, and the recruitment (often forced) of Indigenous people did not always meet all their needs.

Moreover, the Indigenous people of tropical regions, who survived through hunting, fishing, and gathering, had a completely different attitude toward work for sustenance. They did not have the drive to collect (catch or hunt) more than they would eat or to work day after day to create reserves. At the same time, colonists in both Spanish and Portuguese America wanted to extract more and more products from them. Reports sent to the Portuguese crown in the first half of the 16th century contained numerous accounts of hunger among settlers. This was due to the organization of food supply and a prejudiced attitude toward local products, not a lack of resources.

Nevertheless, crops such as manioc, corn, and potatoes did eventually make their way into the settlers’ diets, although they were initially intended for the Indigenous peoples. In some regions of Spanish America, these products were used as a form of tax collected from the local population. Later, they continued to be consumed alongside imported wheat, rice, and certain types of legumes. As for wine, it was imported for a long time and became a luxury item. By regulating its supply, the mother countries aimed to increase the colonies’ dependence and tie them more closely to the metropolis. However, by the second half of the 16th century, grapevines began to be cultivated in Spanish territories in what is now Peru, followed by Paraguay, Argentina, and Chile. The inhabitants of Portuguese America, with its specific climate conditions, relied more on imported wine, and large-scale production began only in the 19th century.

The first agricultural animals brought by the Spanish were pigs and cattle. These were not only kept near settlements but were also deliberately released on uninhabited Caribbean islands as a backup food source for sailors who might go off course or be shipwrecked. After being introduced to the Antilles, they were also brought to other regions of Spanish America. European pigs quickly adapted to the new environment and began feeding on tropical vegetation. Pietro Martire d’Anghiera and Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés noted with satisfaction how the new diet improved the taste of these pigs’ meat.

Globally, the new food base for pigs and cattle allowed them to reproduce quickly, and due to the lack of natural predators, they significantly altered the ecological balance of certain regions (such as the Caribbean islands). However, European colonizers did not think in these terms: they sought to provide familiar meat-based food for themselves, the fleets arriving from the mother countries, and the conquest expeditions of Hernán Cortés, Francisco Pizarro, Hernando de Soto, and others. In addition, cattle were needed by the colonists as draft animals on plantations and in mines.

Where Did Native Americans Come From — Have They Always Been in America or Did They Arrive from Somewhere Else?

North and South America were settled relatively late in human history. At the end of the Ice Age, Upper Paleolithic Siberian tribes crossed into America via the Bering land bridge (now the Bering Strait) and spread throughout both continents in about 1,000 years. Genetic analysis has shown that all Native Americans — from Aleuts and Eskimos to various tribes of Tierra del Fuego — are closely related. For a long time, the oldest archaeological culture in the New World was considered to be the Clovis culture, discovered in the 1920s and 1930s, in what is now New Mexico.

This culture emerged around 15,000 years ago. Over the past two to three decades, the discovery of several pre-Clovis sites (most notably the Monte Verde culture in southern modern-day Chile) has shifted the date of settlement of the New World back by 2,000–3,000 years — it is now believed to have occurred around 15,000–16,000 years ago. Earlier datings (up to 31,000–26,000 BC) are disputed and, although not yet rejected by the scientific community, are not widely accepted by most researchers.

How Many Were There, How Did Different Tribes Live, and What Do We Know About Them?

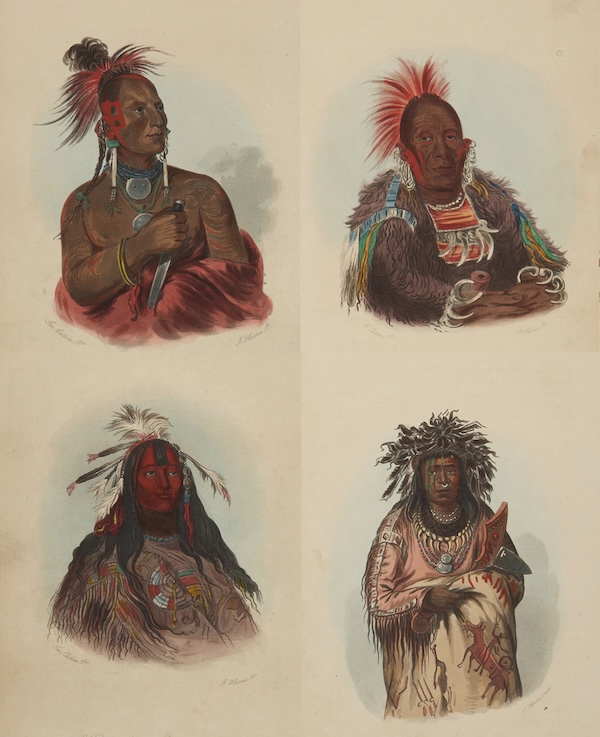

European conquerors encountered a variety of complex societies in the New World, ranging from semi-nomadic tribes of hunters, fishers, and gatherers to powerful state entities like the Aztec and Inca empires. Over a thousand Native American languages are known, forming hundreds of diverse language families. Attempts to reconstruct a Proto-Indian language, spoken by the first settlers who crossed the Bering Strait, have not been successful so far.

Native Americans were unable to put up significant resistance to Europeans. Despite their remarkable achievements in certain areas (such as astronomy), even the most advanced societies did not have knowledge of the wheel, gunpowder, or iron (occasional iron finds do not change the overall picture). Native Americans used bronze for making ornaments and ceremonial objects but not for weapons. This imbalance in technological development is due to the isolation of the New World from the rest of the world.

The question of the native population’s size at the time of America’s discovery is highly ideological and tied to debates about genocide. Estimates vary widely, ranging from 8 million to more than 100 million people. Venezuelan researcher Ángel Rosenblat (1902–1984) estimated the indigenous population of the New World at the time of conquest to be around 13.3 million, and by 1650, around 10 million. In textbooks, you may often see the figure of 55 million; this data is provided by North American geographer William Denevan. In his later works from the early 1990s, he refined this estimate to 53.9 million ± 20%.

How Did the Genocide of Indigenous Peoples Occur and Why?

South America

To address this complex issue, it’s essential to start with definitions. The 1948 UN Convention defines genocide as acts committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group. Clearly, this definition was shaped by the tragic events of the 20th century and cannot be automatically applied to earlier historical periods. At first glance, there seem to be numerous grounds for discussing the genocide of the Indigenous populations of Latin America: the fall of pre-Columbian civilizations after encountering the conquistadors; the complete disappearance of the native population in Cuba and almost complete disappearance in Argentina and Uruguay; significant losses among Indigenous peoples in the tropical and coastal zones of South America; and the massive mortality caused by diseases introduced by Europeans and by forced labor in mines and plantations.

On the other hand, European contacts with Indigenous peoples were varied, the policies of colonial authorities were inconsistent and often contradictory, and there were significant discrepancies between laws imposed from Europe and the local conditions. This diversity prevents us from reducing the entire picture to systematic and methodical genocide. However, the tradition of attributing solely atrocities and bloodshed to the Spanish is not new and has persisted for several centuries. This is also influenced by the so-called “Black Legend”—a strongly anti-Spanish narrative spread by opponents of the Habsburg dynasty in Europe as the Spanish Empire conquered more and more territories.

However, from a historical perspective, when the scale of the loss among the Indigenous population became apparent, one cannot help but think about the destruction of Indigenous peoples—even if it was involuntary and collateral, rather than conscious and intentional (for example, when the pretext was a war against pagans, idolaters, or those practicing human sacrifice). To call it genocide, it must be proven that the colonizers consciously intended to wipe out the Indigenous peoples rather than subjugate, pacify, or conduct a demonstrative act of intimidation, and so forth. There were instances when subjects of the Spanish king pursued policies that led to the destruction of Indigenous peoples, while the king himself condemned these “excesses” and declared that such actions contradicted service to him and God.

Modern historians disagree on whether the term “genocide” applies to the events of the Conquista. Some remind us of a range of aggravating circumstances beyond direct massacres: the removal of leaders as a blow to communities and entire tribal alliances; the relocation of enslaved Indigenous peoples from “useless” areas to regions where labor was needed, resulting in enormous losses; ecocide, or the destruction of ecosystems in which traditional pre-state societies had been integrated for centuries; and sexual violence against women. Opponents of equating the Conquista with genocide argue that the Spaniards’ brutality was driven by the desire to subjugate and later exploit the Indigenous peoples, not to annihilate them entirely. Others emphasize that in the demographic catastrophe that befell the Indigenous population of Latin America, European-introduced infections were more to blame than the extermination by conquistadors. Finally, some point out that alongside the military actions of the conquistadors on the ground, extensive legislation was developed in Spain throughout the 16th century, declaring the protection of Indigenous peoples. Although the practice of the Conquista often involved the voluntary or involuntary extermination of Indigenous peoples, theoretically, something entirely different was proclaimed.

Beyond the question of genocide during the Conquista, researchers address related issues: ecocide and ethnocide. The previously mentioned ecocide refers to the predatory exploitation of natural resources by Europeans in the pursuit of profit and the destruction of ecosystems in which the lives of hunter-gatherers in the Caribbean and continental tropical zones were embedded. It includes the colonization of the Caribbean islands, which led to the rapid (within a few decades) disappearance of the Taíno tribe and several others, as well as the significant reduction of Atlantic coastal forests in Brazil due to the cutting down of valuable redwood. A key element in the modern struggle for the rights of the Amazonian Indigenous peoples is the preservation of the natural environment in which they live.

As for ethnocide, it is understood as the destruction of an ethnic group through the eradication of its culture and the prevention of the use, development, and transmission of its language and culture to subsequent generations (including religious beliefs). Indeed, it is undeniable that the Spaniards and Portuguese sought to convert the Indigenous populations of Latin America to their religion and impose a Christian way of life. None of the defenders of the Indigenous peoples in the 16th–17th centuries—be it Padre Bartolomé de las Casas or the Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits who saved the Tupi-Guarani from brutal slave hunters—questioned the superiority of Christianity over paganism and the impossibility of preserving the old rituals and way of life. They were driven by a sincere belief in the only possible salvation of the soul through the acceptance of the Catholic faith. The realities of the Conquista showed that the slogans of spreading Christianity for the good of the Indigenous peoples too often masked looting and ruthless exploitation. Nevertheless, contemporaries objected only to the methods of conversion, not to its overarching goals.

Thus, based on the 1948 UN Convention, the actions of Europeans in South America during the Conquista and colonization were not genocide. The most comprehensive general formulation, which seems acceptable to both opponents and supporters of the idea of genocide, is as follows: a violent alteration of the destinies of peoples after the Old World discovered the New and subjugated it.

North America

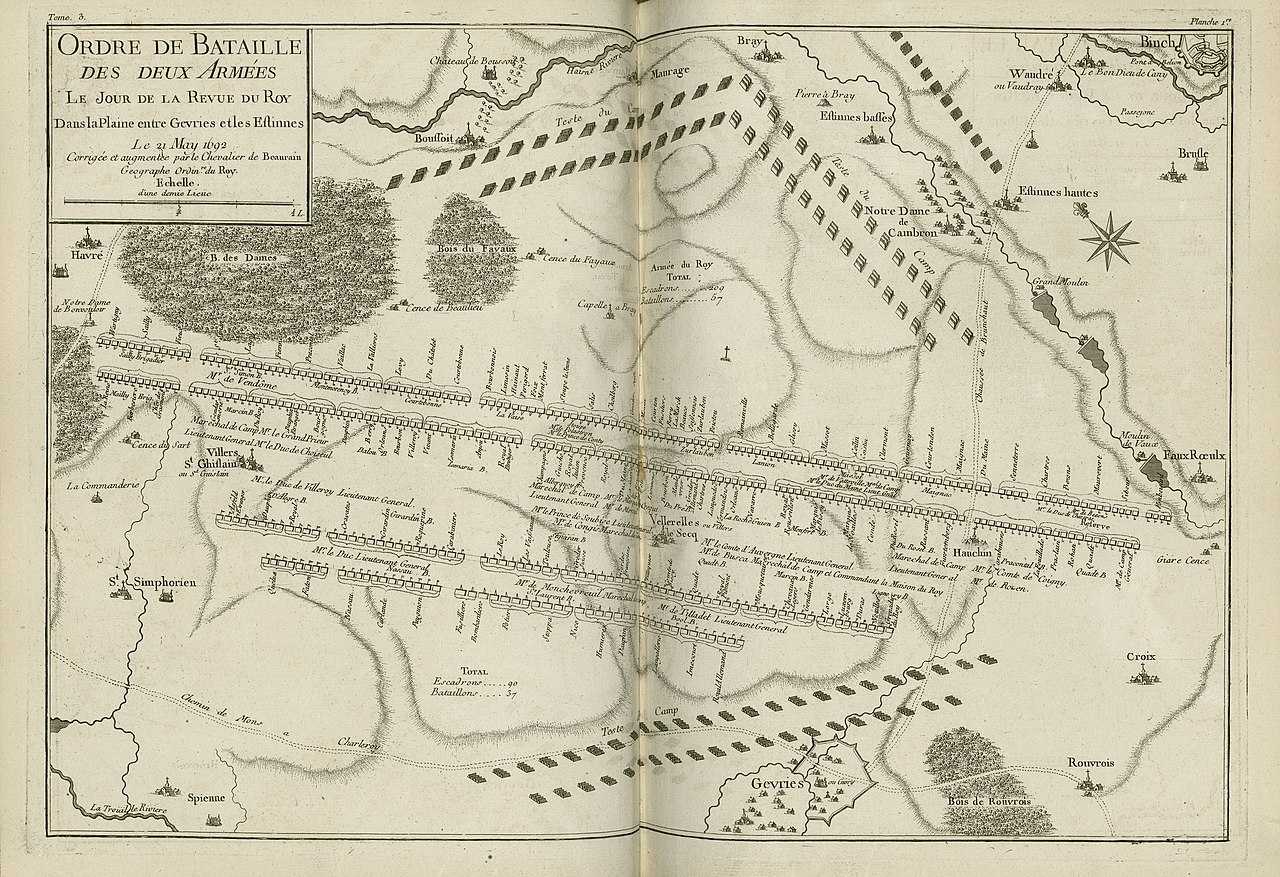

In North America, the population density of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples during the colonial era was significantly lower. Nevertheless, European colonization also led to wars and the gradual displacement of Indigenous peoples deeper into the continent. The first encounters between Indigenous peoples and the Spanish and French in North America date back to the 16th century. Wars between white settlers and Algonquin Indigenous peoples began in Virginia (1622) and New England (1637, 1675–1676). Then came wars with the Iroquois, Muscogee, and Sioux (from 1675 onward). However, there were cases when European powers, on the contrary, sought to enlist the military support of the Indigenous peoples. For example, the Seven Years’ War (1754–1763) in British North America became known as the “French and Indian War.”

In 1763, British authorities prohibited settlers from moving west of the Allegheny Mountains, explaining their decision as being in the interest of Indigenous peoples. However, this decision ultimately was not implemented—independence movements soon began.

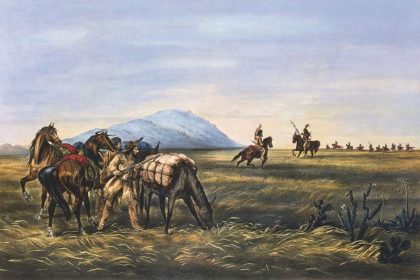

The true catastrophe for the Indigenous populations of the United States was linked to the rapid agricultural development of vast areas of the continent in the 19th century. In 1830, the U.S. Congress passed the “Indian Removal Act,” forcibly relocating Indigenous peoples from the Atlantic coast to lands west of the Mississippi River. A series of wars did not halt the federal government’s decision. In 1831, the U.S. Supreme Court recognized Indigenous tribes as “domestic dependent nations,” for which the U.S. government essentially bore guardianship responsibilities. Although the Supreme Court restored the tribes’ sovereignty in 1832, their relocation did not stop. The Cherokee, Creek, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw were sent along the “Trail of Tears” to what is now Oklahoma.

The Dawes Act (1887) destroyed the rights of Indigenous communities—tribal self-government and their collective land ownership—leaving almost all of them, beyond the borders of the so-called Indian Territory, with individual plots of 160 acres (64.8 hectares), the same amount an ordinary settler could receive under the Homestead Act. This was a very large allotment for irrigated farming but did not allow for the continuation of traditional economies. Senator Henry Dawes (1816–1903) believed that his law would speed up the transformation of Indigenous hunters into progressive, prosperous farmers.

The outcome was different. During the years the law was in effect (until 1934), Indigenous peoples lost nearly two-thirds of their lands. On December 28–29, 1890, U.S. troops crushed the Sioux uprising at Wounded Knee in South Dakota. This last armed conflict with the Indigenous population of the U.S. coincided with the end of the “moving frontier” era—the completion of the country’s internal rural colonization: vast expanses, where only recently one could encounter only Indigenous peoples, were plowed in just a few decades. If in 1800 the total Indigenous population in the U.S. was about 600,000, by 1900 it had reached the lowest point in North American statistical history—fewer than 240,000.

The governments of not only the U.S. but also other New World countries sought to break up Indigenous communities and replace communal land ownership with private property. Their goal was to create a unified land market and eliminate “feudal remnants.” These measures were most consistently implemented in Mexico. The Lerdo Law (1856) prohibited corporate (i.e., non-individual) land ownership, which immediately dealt a powerful blow to Indigenous peoples who could not keep up with the re-registration of their land rights (another victim of the law was the Catholic Church). The Law on Colonization of “Vacant Lands” (1883), in particular, led to the direct seizure of Indigenous lands in Sonora and Yucatán. As a result, if in 1821 communal land ownership accounted for 40% of agricultural land, by 1910 it was no more than 5%. The situation of the Indigenous peoples became dire in Argentina, where, as in the U.S. and Canada, a powerful settler movement and effective market agriculture emerged in the last third of the 19th century.

How Did Mexico, the USA, and Canada Come to Be?

Mexico

All these modern countries are geographically part of North America, but historically and culturally they represent different regions. Mexico is part of Latin America; after the discovery of the New World, it became part of Spain’s colonial possessions. The USA emerged from British colonies, though some of its modern territories were once Spanish and even French colonies. Modern Canada includes lands that belonged to both the French and British crowns.

Of all these countries, Mexico experienced the earliest systematic European colonization. As early as 1519–1521, the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) conquered the Aztec Empire, and in the 1540s, the Spanish subdued the Maya states. Gradually, a system of governance for Spanish America developed, and in 1535, the Viceroyalty of New Spain was established. It became the first of the viceroyalties into which Spanish possessions in America were divided. The significance of New Spain, which was one of the most densely populated and economically developed regions of the New World even before the conquest, increased with the discovery of silver mines in the 1540s.

Like the other viceroyalties, New Spain lasted until the early 19th century. After Napoleon Bonaparte increasingly subjugated the Spanish monarchy, forcing King Charles IV of Bourbon and his heir to abdicate in favor of Napoleon’s brother Joseph in May 1808, juntas (representative bodies) began to emerge in Spain and its overseas territories. These initially ruled in the name of the rightful king, Ferdinand VII, son of Charles IV. In Mexico City, the capital of New Spain, such a junta appeared in August 1808. Unlike the viceroyalties of New Granada and Rio de la Plata, where the struggle for independence was initiated by the Creole elite—descendants of Spaniards who felt more American than European—in New Spain, the independence movement developed from below. On September 16, 1810, the priest Miguel Hidalgo from the village of Dolores in Guanajuato (central Mexico) called for a fight for freedom—known as the “Cry of Dolores.” This sparked a struggle for Mexican independence that divided the country.

On February 24, 1821, the commander of Spanish forces in southern Mexico, Agustín de Iturbide, issued the “Plan of Iguala” (named after a town in southwestern Mexico) under the slogan “Religion, Unity, Independence.” It declared Mexico a constitutional monarchy, guaranteed the preservation of the Catholic Church’s privileges, and proclaimed equality for all Mexicans, regardless of race or origin. The “Plan of Iguala” became the historical compromise that united the forces of radicals and conservatives in the struggle against the authority of the metropole.

On September 28, 1821, the Act of Independence of the Mexican Empire was proclaimed, but by March 1823, the republicans had overthrown Emperor Agustín I Iturbide. On October 4, 1824, the republican constitution of the United Mexican States was published.

USA and Canada

The first permanent British colony in the New World, Virginia, was founded in 1607. The War of Independence began in 1775 in 13 British colonies in North America—excluding Canada, which was incorporated into the British Empire only after the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763), and the island possessions in the Caribbean. The struggle concluded in 1783 with the signing of the Treaty of Paris, under which London recognized the independence of the new state—the United States of America.

The exploration of Canada began with the Italian John Cabot (Giovanni Caboto), who landed on the coast of Newfoundland in 1497, serving the English crown. He was followed in the early 16th century by French expeditions led by the Florentine Giovanni da Verrazzano and Jacques Cartier, whom the Indigenous people guided to Canada (meaning “village” in the Iroquois language). The actual colonization of Canada by the French began with Samuel de Champlain’s establishment of Quebec City in 1608. Following the Treaty of Utrecht, which ended the War of Spanish Succession in 1713, France lost Acadia, and by the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the British Empire acquired Quebec, bringing Canada entirely under its control.

During the Revolutionary War -or American War of Independence- (1775–1783), both new British settlers and the French in Canada remained loyal to London. It was during this time, in 1774, that the Quebec Act was passed, securing the rights of French Catholics. In 1841, the English-speaking Upper Canada and the French-speaking Lower Canada, created in 1791, were unified. In 1867, the British North America Act created the Dominion of Canada, a self-governing possession of the British Empire. The legal concept of a “Dominion,” which existed until 1949, was initially developed for Canada and later extended to Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Ireland, and Newfoundland, which was incorporated into Canada only in 1949. Canada became fully independent in 1982 with the passage of the Canada Act, despite retaining membership in the British Commonwealth.

What is the Oldest City in America?

To answer this question, we must make some clarifications. Firstly, it’s essential to distinguish between cities founded by Europeans and those of ancient American civilizations, the oldest of which likely date back to the 1st millennium BCE. These did not survive the era of the Conquest in their original form, although some cities of Spanish colonists emerged on their ruins. The most prominent example is Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan.

If we talk about cities founded in the New World by Europeans, the undisputed primacy belongs to Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola. It was established in 1496 by Bartolomeo Columbus, the brother of Christopher Columbus. If we look at the mainland, the uncontested oldest city in Central America is Nombre de Dios in Panama, founded by Diego de Nicuesa in 1510. In South America, the oldest existing city (again, with the caveat that we do not consider pre-Columbian cities) appears to be Santa Marta on the current territory of Colombia, founded by Rodrigo de Bastidas in 1525.

Finally, in North America (excluding Central America, meaning in the territories of the USA and Canada), the oldest city is St. Augustine (Spanish name San Agustín), located in what is now the state of Florida, USA. In 1564, a French fort named Fort Caroline was established there, but the following year, the Spanish admiral Pedro Menéndez de Avilés destroyed the French colony and established Fort San Agustín in its place.

How the Discovery of America Affected the European Economy

The discovery of America had a profound impact on the socio-economic development of Europe. As major trade routes shifted from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic, some regions lost their former prominence (Italy, Southern Germany), while others gained significantly in strength (Spain and Portugal, later England and the Netherlands). The large-scale importation of American precious metals doubled the amount of gold and tripled the amount of silver circulating in Europe, contributing to a rapid increase in prices for essential goods (the so-called “Price Revolution”) across Europe

A significant portion of the precious metals arriving in Europe was immediately exported to Asia, where they were used to purchase expensive Eastern goods. However, some silver remained in Europe. The increase in the money supply, along with the potential of colonies as sources of raw materials and markets for European goods, contributed to the development of the European economy. At the same time, the causes of the “Price Revolution” and other new socio-economic processes required explanation and stimulated the development of economic thought, particularly in Spain.

As a result of the discovery of America, not only did trade contacts with Europe rapidly expand, but systemic connections also developed between Asia and America (embodied in the Manila galleons—huge ships that sailed between Manila in the Philippines and Acapulco in Mexico), as well as between America and Africa. In the Atlantic in the 16th and 17th centuries, a triangular trade route developed: ships carried European goods to Africa, transported enslaved people to the New World, and returned to Europe with cargoes of tobacco, sugar, and other goods. All of this indicated the formation of a global market.

Paradoxically, the economies of the Iberian countries, which were the first to establish colonies in America, ultimately found themselves at a disadvantage. First, emigration to the colonies created huge demographic problems for Spain and especially for Portugal. Second, their economies could not meet the needs of their overseas possessions, forcing authorities to open the way to America for merchants from more developed countries, who in turn began to dominate the economies of the metropolises to some extent. “These kingdoms are becoming poorer every day and are turning into Indies for foreigners,” complained deputies of the Castilian Cortes in the mid-16th century.

Along with the economy, politics also expanded onto the vast oceans. Competition for control over trade routes, the desire of European powers to acquire their own colonies, and the struggle for their redistribution became an integral part of international relations. Thanks to the wealth of the colonies, the metropolises significantly strengthened their positions in Europe.

How Did It Change European Culture?

The scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries became possible in large part because the discovery of America, as a key component of the Age of Discovery, led to a dramatic expansion of Europeans’ understanding of the world. In America, new extensive materials were collected for the natural sciences, ethnography, history, and linguistics. Contacts with indigenous tribes, who had different social structures, stimulated the development of social thought. By gaining experience in interacting with bearers of different cultures and religions, Europeans became more aware of their own cultural and historical unity.

At the same time, the most critically-minded among them realized that the world is diverse, that foreign cultures and religions may be no worse than their own, and that Europeans could learn much from the inhabitants of distant lands. It is no coincidence that the famous French humanist Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) emphasized that in terms of morality, Native Americans were in no way inferior to Europeans, and Thomas More placed his ideal island of Utopia near the shores of South America. Alonso de Ercilla, in his epic poem “La Araucana,” describing the wars of the Spaniards with the Araucanian Indians, does not question Spain’s right to subdue them but effectively presents them in a heroic light as fighters for freedom, whose truth is equated with that of the Spaniards. Spanish humanists and clergy (Bartolomé de las Casas, Vasco de Quiroga, and others) attempted to implement utopian ideas in the New World that were born in Europe. Reflections on the Golden Age and the unspoiled faith of the inhabitants of America were organically woven into the intellectual world of the Renaissance and the Reformation.

The discovery of America and the subsequent Conquista inspired literary works of various genres: Hernán Cortés’s “Letters,” Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s “Shipwrecked Survivor’s Report,” and others. Innovative compilations appeared that contained information about the geography and nature of the new lands, as well as the customs and history of their peoples: “Decades of the New World” by Pietro Martire d’Anghiera, “History of the Indies” by Las Casas, “General History of the Things of New Spain” by Bernardino de Sahagún, and others. Images of America from the Age of Discovery and Conquista can also be traced in European literature and art, particularly in the works of Shakespeare and Calderón.

And the Food?

Europeans were introduced to new types of poultry (turkeys), agricultural crops (potatoes, corn, tomatoes, beans, red chili peppers, pumpkins, cocoa), and fruits (pineapple, avocado). Although the introduction of new products was delayed due to the conservative mindset of most colonists, over time, they significantly changed the diet of Europeans, causing a sort of “food revolution.” Particularly important were potatoes and corn, which significantly reduced the threat of famine. The influence of crops brought to America by Europeans and actively cultivated there for export to the Old World (coffee, sugarcane, from which not only sugar but also rum was made) was also substantial.

Tobacco deserves special mention: it is not an edible crop, but was initially valued by Europeans as a remedy for hunger; it was also used as medicine (recall that later Robinson Crusoe used tobacco tincture for treatment on his deserted island). Eventually, chewing, sniffing, and smoking tobacco became popular in the Old World for pleasure. Tobacco became the main crop in British Virginia and Maryland in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Spanish also introduced bananas to the island of Haiti, which are now considered an integral part of American flora. There are hypotheses that bananas were known in South America even before the arrival of Europeans; in any case, it was the Spanish who spread them widely throughout their territories.

European colonists also contributed to the spread of American species of cultivated plants and domesticated animals beyond their original habitats. For example, they brought the Mexican-origin turkey to Peru. Over time, the mixing of indigenous and European food products and methods of preparation led to the creation of a unique cuisine on both sides of the Atlantic. Some dishes that became traditional on both sides of the Atlantic include imported ingredients, but their American or European origins have been forgotten (for example, the Spanish potato tortilla—not to be confused with the Mexican corn tortilla—or dishes based on rice and milk from Argentina).