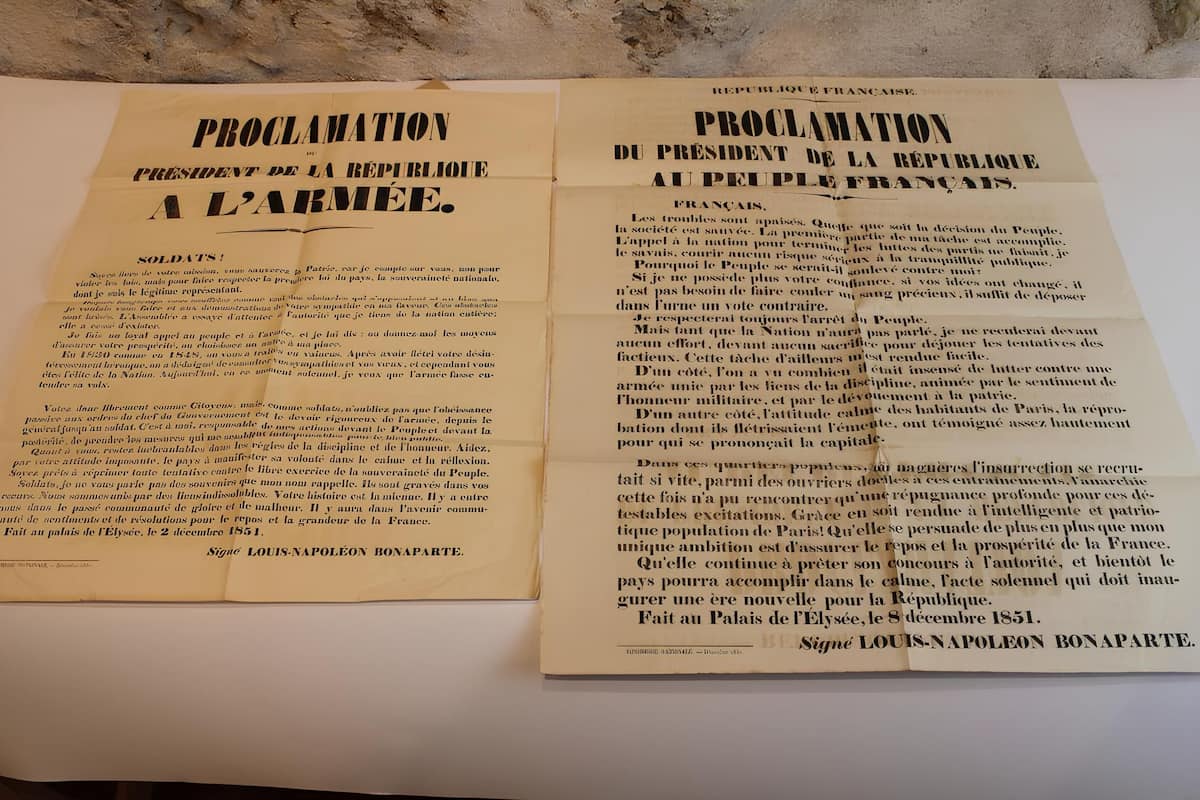

Paris wakes up under the rain on Tuesday, December 2, 1851. Early risers gather in front of white posters plastered on the walls: a decree and two proclamations. The first announces the dissolution of the National Assembly and the forthcoming convocation of the electors. The first proclamation addresses the army, the “elite of the nation,” invited to defend “national sovereignty.”

In the second, the head of state, Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, speaks in the first person: “My duty […] is to maintain the Republic and save the country by invoking the solemn judgment of the only sovereign I recognize in France, the people […].” The impact is total. The very first president elected by universal male suffrage in 1848 had just perpetrated the first coup d’état of the democratic era.

—>Louis Napoleon Bonaparte, as the President of the Second French Republic, orchestrated the coup to dissolve the Republic’s democratic institutions, dismiss the legislative assembly, and establish himself as the ruler, paving the way for the establishment of the Second French Empire.

How Did France Get to This Situation?

Four years earlier, like all the Bonapartes, the one demanding full power was still banished from French territory. Returning from exile in the wake of the February 1848 Revolution, following the fall of the July Monarchy, this eternal conspirator was brought to power on December 20, 1848, by the Party of Order. More of an informal coalition than a structured party, it brought together mainly monarchist nostalgics.

At the end of his four-year presidential term, this “fool who will be led,” in the words of Adolphe Thiers, should have stepped aside in favor of a monarchist candidate. Shunned by both conservatives and Republicans, the presumptive heir to the imperial throne was constantly at odds with the Assembly over his extravagant lifestyle.

However, in the face of this supposed puppet, the political void was abyssal. “The Reds were strong but a minority. The rest consisted of political cliques without massive popular support,” notes historian Louis Girard (in his Napoleon III, ed. Fayard, 1986). Yet, no one reached the popularity of Napoleon’s nephew, renamed the “prince-president.” The problem: according to the 1848 Constitution, the head of state, elected for a four-year term, could not serve a second term. Legally, only a constitutional revision would allow him to retain power.

The Coup d’état of 2 December 1851

The president, like any candidate in a campaign, meticulously curated his image. He conducted numerous tours among the “common people” and the military, showering them with attention. With the support of the people and the army, the head of state was confident in his ability to bend the Assembly to his will. He almost succeeded. On July 19, 1851, the deputies narrowly rejected the constitutional revision.

Consequently, he was legally unable to extend his mandate. From that moment, in homage to his admired figure, Caesar, Louis-Napoleon resolved to take the irrevocable step by initiating a coup d’état.

An inexorable mechanism was set in motion. After leading the Republic for three years, Louis Napoleon had control over all the levers of power: the government, the army, the administration, and the police. Initially, he assigned roles: his half-brother, Count de Morny, the mastermind behind the coup, would take on the Interior portfolio; the prefect of Haute-Garonne, Emile de Maupas, his protege, was promoted to the police prefect of Paris; and the ambitious General Saint-Arnaud was entrusted with the Ministry of War.

On November 1, 1851, the latter issued a circular to the military reminding them of their duty of “passive obedience.” Subsequently, he set a date. The conspirators initially considered surprising the deputies during the Assembly’s vacation, between August and October. The D-day was postponed four times before settling on December 2, a doubly symbolic anniversary marking the imperial coronation of Napoleon Bonaparte (1804) and the victory at Austerlitz (1805, Battle of Austerlitz).

The Murder of Jean-Baptiste Baudin, MP for Montagnard

The day before, as is customary every Monday, a ball had been held at the Elysée. While crinolines swept the floor, Maupas, the police prefect, individually met with the 48 commissioners of the capital. Pretending an imminent threat of a plot, he ordered them to arrest representatives of the opposition. Before dawn, 78 personalities were apprehended, most of them in their sleep. Among them was Adolphe Thiers, the former critic of Louis Napoleon.

Earlier, the famous white posters had been taken to the National Printing Office. As a useful precaution to prevent workers who were quick to revolt from hesitating, the text had been composed in fragments. At 6 in the morning, the Rubicon was indeed crossed: the posters were plastered, the Palais-Bourbon was occupied, and 54,000 soldiers were deployed.

“When the opposition manifests itself, the coup d’état is already consummated and successful,” comments political scientist Emmanuel Cherrier in “December 2, 1851, the archetype of the coup d’état” (Napoleonica Review, vol. 1, 2008). During the morning of December 2, the Parisians indeed remained calm.

“In June 1848,” specifies Louis Girard, “the blacksmiths and ironworkers of the North had almost all risen; on December 2, 1851, the workers were at work, and the shops were open.” The Assembly’s monarchist majority had long eroded public support. So, what was the point of defending it?

Around 11 o’clock, the coup president decided to go out. On the Champs-Elysées, he received a burst of cheers from the troops. At the same time, about 300 deputies—mainly monarchists—voted for the deposition of the head of state and demanded the support of the army. The military immediately responded to the call to lead the protesters to prison. “After one or two days of symbolic captivity,” writes Louis Girard, “the deputies will be released.”

The proponents of the Party of Order were now neutralized. Meanwhile, the Republicans entered the fray. Hunted by the police, a few dozen representatives of the people appealed for insurrection. Among them was Victor Hugo.

On the evening of December 2, Paris still did not flinch. The conspirators were on easy ground. On the morning of December 3, a few barricades began to be erected under the exhortations of about twenty socialist-democrat deputies, adorned with their tricolor sashes, including Alphonse Baudin. Interpellated by a worker who asked, “Do you believe that we are going to get killed to preserve your 25 francs a day?” (the daily allowance for parliamentarians), the deputy retorted, “You will see how one dies for 25 francs!”

A cruel chance: a bullet shot from the barricade just after, injuring a soldier. His comrades immediately retaliated, and Baudin fell, fatally wounded. His disappearance immediately made him an icon of the Republic. Eventually, agitation won over the republican strongholds of central and eastern Paris. As historian Eric Anceau observes, “The people became an actor when Louis Napoleon wanted it to be a simple judge of the accomplished fact” (“The Coup d’État of December 2, 1851,” in Parlement[s], political history review, 2009). The Minister of War, General Saint-Arnaud, hardened his stance: “Any individual caught building or defending a barricade or with weapons in hand will be shot.”

It is Impossible to Prevent People From Protesting

On the following day, December 4th, 1,200 insurgents roamed the old Paris. This was twenty times fewer than in June 1848. However, the tension was palpable: 30,000 soldiers marched on the city. At 3 p.m., in the Boulevards district, a group of “yellow gloves”—a nickname for the patrons of chic cafes—challenged the troops with cries of “Long live the National Assembly.” Had a provocative shot been fired? No one knew. In a panic, the soldiers opened fire without order or warning. On Boulevard Montmartre, even the cannon spoke! 380 people—1,200, according to Victor Hugo—collapsed under the bullets. The City of Light, paralyzed, would move no more.

The Province Goes Up in Flames

As Paris dimmed, the provinces ignited. In Provence and Languedoc, regions aligned with the Republicans, the heart of the uprising was particularly strong. In Manosque, the “red city” of Basses-Alpes, the democratic-socialist mayor led bands of poorly armed peasants to confront the Bonapartists.

Republican columns seized control of the prefecture of Digne and occupied it for several days. In the neighboring Var department, thousands of protesters were arrested, and about a hundred were killed. From December to January, 32 departments in Hexagone (out of a total of 86) were placed under martial law, resulting in nearly 27,000 people being charged. A third would be released, a second deported to Algeria or Guyana, and the rest would be incarcerated or placed under police surveillance.

According to the American historian Ted W. Margadant, this extensive sweep constituted ‘the most significant police repression outside Paris between the White Terror of the 1790s and the Resistance during World War II.”

Bloodbath

In January 1852, the Bonapartist order prevailed throughout France. However, it came at a significant cost. The regime swiftly legitimized bloodshed. Narratives of rapes, looting, and hostage-taking perpetrated by the insurgents circulated in the official press. In Paris, the orchestrators of the coup claimed to have thwarted a monarchist plot; in the provinces, they asserted to have quelled the beginnings of a “jacquerie.”

Moreover, they claimed to have suppressed the latent social revolution. The December 1851 putsch had indeed circumvented a dual deadline: the election of the new president and that of a new assembly. The latter, dominated by the conservative right, could have shifted towards the “reds” in May 1852. This, at least, was the fear of a portion of the population.

It is undeniable that the Republicans, crushed in the legislative elections of May 1849 under the label “democratic-socialists,” hoped for a comeback. To the bitterness of defeat was added a new humiliation by conservative deputies: on May 31, 1850, they repealed universal male suffrage in favor of limited suffrage, subject to residency conditions. A significant portion of the left-leaning electorate, including peddlers and seasonal workers, had been struck off the voter rolls.

The Republicans then withdrew into covert societies or neighborhood organizations run by town leaders. This “enlistment” of rural areas, aimed at regaining control of the Assembly, paved the way for the December uprising. “On the left,” writes Eric Anceau, “the year 1852 had become the object of messianic anticipation.” The Bonapartist coup would prove them wrong.

The rest is known. On December 20 and 21, 1851, less than three weeks after the coup, while a third of the territory was still under martial law, a plebiscite asked the French whether they wished to maintain their trust in the president. The answer: Yes. The consultation was even a triumph, especially in regions swept by repression: 7,439,216 “yes” votes against only 640,737 “no” votes.

The era of the “dictatorship of public safety” begins, where the head of state, the sole master on board, consolidates all powers. On December 2, 1852, exactly one year after his victorious coup d’état, Louis-Napoleon officially became “Napoleon III, Emperor of the French.” The guardian of institutions thus began by violating the Constitution.

“France understood that I had departed from legality only to return to what is right,” he declared after the victorious plebiscite of December 20, 1851. He then made this involuntary admission: “More than 7 million votes have absolved me.” Did he feel guilty? George Sand, the republican muse, wanted to believe it: received in 1853 by the emperor, she saw “a real tear in that cold eye.” Much later, Empress Eugénie would claim that remorse had tormented him throughout his existence.

As early as the spring of 1852, Louis Napoleon sought to soften the condemnations suffered by the insurgents of December. “As soon as he could,” quips Ted Magadant, “he pardoned the victims who agreed to submit. ” The president may have regretted the spilled blood, but he never disavowed the coup d’état. And for good reason: the majority of the French had approved it. Out of fear of the “reds,” disdain for the Assembly, or simple indifference.

Posterity, however, will be decidedly more resentful. “Since 1852, anyone claiming to be a republican in France cannot lend a hand to a coup d’état or become its apologist,” emphasizes historian Eric Anceau.

Louis Napoleon will embody the excesses of executive power for generations. Proof of this is that in 1964, when François Mitterrand, then a deputy from Nièvre, wanted to denounce the Bonapartist excesses of the Fifth Republic and its president, Charles de Gaulle, he used the term “permanent coup d’état.” Only to eventually accommodate the institutions and the presidential prestige once he came to power in 1981.