The Battle of Austerlitz took place on December 2, 1805, pitting the forces of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte against the armies of the Russian Emperor (Alexander I) and the Austrian Emperor (Francis II). Also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, this decisive French victory, achieved on the anniversary of the emperor’s coronation, overshadowed the naval disaster at the Battle of Trafalgar and effectively concluded the Third Coalition War in favor of the French.

Napoleon, recognizing it as a personal triumph and a potent tool to legitimize his power, did not bestow any ducal or princely titles of Austerlitz upon his marshals. The day after, addressing his army, the emperor expressed satisfaction: “My people will welcome you back with delight, and all you will have to say is ‘I was at the Battle of Austerlitz’, for them to reply, ‘There goes a brave man.'”

Where Did the Battle of Austerlitz take Place?

The battlefield of Austerlitz is located about ten kilometers southeast of Brno, the capital of Moravia, which was then an Austrian province. In 1805, it was a rural area situated between the wooded slopes of the Moravian hills and the marshy course of the Schwarzawa. After capturing the main Austrian army at Ulm five weeks earlier, Napoleon was led to this region north of Vienna by the pursuit of what remained of Emperor Francis II’s forces. The latter had indeed abandoned the defense of his capital to meet his Russian counterpart, Alexander I, the other main instigator of the coalition formed against Napoleon’s France at the instigation of England.

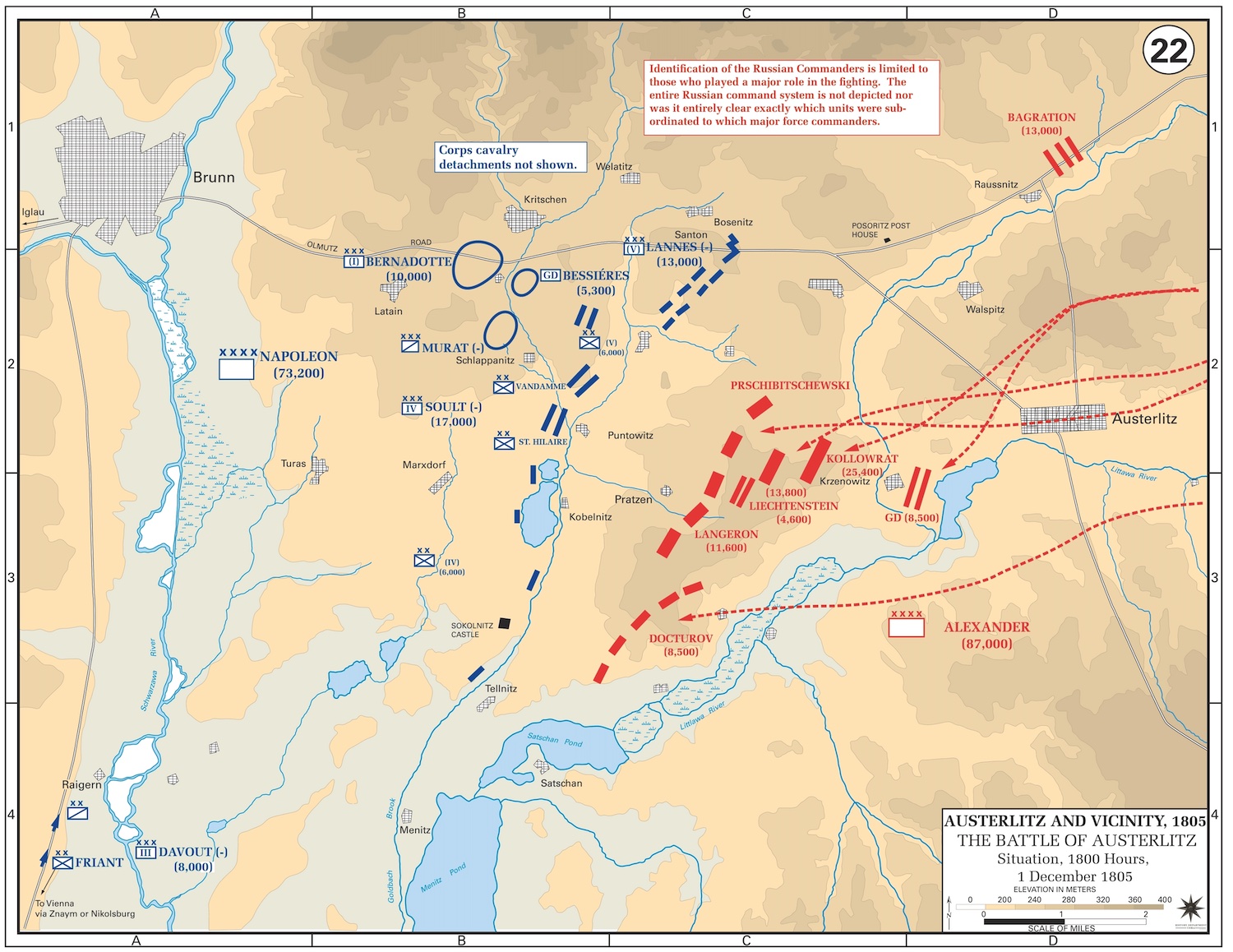

Let’s highlight some figures to grasp the magnitude of the battle: Austerlitz was a conflict lasting just over half a dozen hours, involving around 160,000 soldiers (approximately 75,000 French against 60,000 Russians and 25,000 Austrians) on a battlefield not exceeding, like most of that era, 150 km2. In just a quarter of a day, it cost the victors 9,000 killed, wounded, and captured, while the vanquished suffered 27,000 casualties. Even victory is written in letters of blood, with 1,300 killed and 7,000 wounded on the French side.

Preparing for Battle

On the evening of December 1, 1805, a peculiar scene unfolded from the French army’s trenches to the south-east of Brünn. The French are stationed in the middle and to the left of the route from Brünn to Olmutz, since this is where the incoming Austro-Russian army would be seen. However, the French right wing is relatively thin and bald farther south. To put it mildly, this is an issue because if the coalition forces break through, they will be able to sever the Brünn-Vienna route, cutting off the remainder of the Grand Army from its supply lines. Napoleon was well aware that the III Corps, under the command of Marshal Davout, had just completed a challenging march from Vienna.

But the French emperor’s blunder was entirely on purpose. It’s a ploy to draw in his adversaries and have them attack his right wing. Attacks from the French center would be most effective if they were to engage along the marshes on the southern end of the battlefield, exposing their own right flank. The world knows about this ruse, which is frequently held up as the pinnacle of Napoleon I’s military brilliance.

Not as well remembered is the widespread intoxication campaign that accompanied it. Since occupying Vienna, France’s emperor has worked hard to give the alliance the impression that he is weaker than he really is. According to this overarching reasoning, the 7,000 Davout soldiers are similarly stuck in Vienna, isolated from the rest of the army.

Rather than anything else, the specifics of the situation should inform your strategic decision. The Prussians, who had remained neutral up until that point, were becoming restless; their potential entry into the alliance posed a major threat to the supply lines, which were already at dangerously low levels. What’s more, it was well into October by this point, and winter was just around the corner. Napoleon could lose momentum and watch his foes become stronger if he waited until the next spring to make a decision if he failed to win a decisive victory early.

So he did all in his power to provoke an assault by the Austro-Russians. And his strategy becomes successful, as Tsar Alexander and the majority of his generals are ready to battle despite the warnings of Emperor Francis and Russian Marshal Mikhail Kutuzov, who is technically in charge. They will fall right into the trap their opponent has laid for them. As Napoleon had predicted, the right flank of the French army was the target of their assault. A vanguard led four columns of Austro-Russians toward the settlement of Telnitz, which was located between the marshes and the plateau of Pratzen.

The Sun of Austerlitz: The Battle of the Three Emperors

Today it was Telnice, a little town between Satcany and Menin in the northwestern part of the country. On the morning of December 2, 1805, the third line infantry unit was tasked with garrisoning the fort. Sokolnice was located a short distance north of here. The city of Sokolnitz was another target of the assault, and it was guarded by just the 26th light infantry unit. The French garrison’s fortifications remained in place. To be more specific, it was northeast of the settlement, which had grown to accommodate a few housing developments and light enterprises.

From seven in the morning onward, Coalitionists launched a series of attacks on the two communities. Conditions on the battlefield were miserable, with chilly rain pouring down. As the leader of the onslaught against the French right flank, General Buxhövden’s soldiers must have been a sight to behold—and dreaded—as they marched closer. The fact that it was so poorly planned just made matters worse. It was still dark when he left, and to top it off, Buxhövden was simply drunk. The coalition army lacked the strict organization into corps, divisions, and brigades that the French army had. A traffic jam formed on the southern slopes of the Pratzen plateau as a result of the return of General Liechtenstein’s 5,000 cavalrymen, who were to stay in reserve.

The French were able to back up the first assault because the vanguard and the four coalition columns didn’t attack all their targets at once. Eventually, however, sheer numbers would win out, and the French were ultimately sent away from Telnitz. They retreated to the opposite side of the Goldbach, a stream whose path can be seen on the satellite picture only as a narrow line of trees running northwest of Telnice and southeast of Sokolnice. The French right flank was not completely destroyed, however; Davout’s III Corps showed up in time to launch a counterattack and recover Telnitz. A charge by hussars will eventually push it back, but with artillery assistance, it may make up lost ground down the Goldbach.

While exhausted from traveling 110 kilometers in two days, Davout’s men arrived just in time to help the other defenders (General Louis Friant’s division) focus on Sokolnitz, from which the French had been driven after a good initial resistance by the artillery of the Russian column commanded by, ironically, a French émigré who had gone into the service of the Tsar, Count Andrault de Langeron. At approximately nine in the evening, after Sokolnitz had changed hands many times, the Russians finally managed to take it. At that point, the French were severely outnumbered, but they wouldn’t have to worry about another assault since the focus of the battle of Austerlitz had abruptly shifted.

The Attack on the Pratzen plateau

Let’s leave Sokolnice and go to Prace in the northeast. In 1805, this was the little settlement of Pratzen, named after the gently sloping plateau on which it was constructed. This eminence towers above the neighboring lowlands by roughly 40 meters. It was quite difficult to make out the slope from above today; the little rural roads curved in various spots were the only discernible landmarks. Napoleon, with his typical tactical brilliance, realized and declared this to be the key to victory before the conflict had even begun.

Having ironed out the Austro-Russians at Telnitz and Sokolnitz, he sent in the Vandamme and Saint-Hilaire divisions of Marshal Soult’s IVth Corps at around nine o’clock. The morning fog lifted just west of Prace as sixteen thousand French infantrymen made their way up the valley. There, the myth of the “sun of Austerlitz” was penned.

It also gave Kollowrat and Przybyszewski, the commanders of the last two Austro-Russian columns, an opportunity to see the gravity of the danger they faced for the first time. As they were stuck in a “traffic congestion” due to Liechtenstein’s error, the French snuck up on them and bayoneted them from behind.

Coalition forces, caught off guard, put up a spirited fight until they lost their footing and dispersed en masse to the east. Just after nine o’clock, Soult had his artillery set up on the Pratzen plateau and firmly under his control. Mohyla Miru, just south of Prace, was the location of the monument dedicated to the combat that took place here.

As the coalition’s advancing wing became more cut off from the remainder of the army, the latter being in imminent danger of being wiped out, the significance of the city of Pratzen became increasingly apparent.

Then, Kutuzov attempted to retake command by launching a pincer assault, with heavy cavalry from Liechtenstein and the Russian Imperial Guard attempting to skirt around the left of Soult’s corps, which had moved to a new position. It did not escape Napoleon’s attention, and he promptly sent the army corps of Bernadotte and the cavalry of Joachim Murat to protect Soult’s left flank. If the French were able to hold Pratzen, they would have won the fight regardless of what happened afterwards.

From the Moment of Decision to the Curse

Starting about eleven o’clock, fierce infantry and cavalry fights broke out in the valleys between Jirikovice and Blazovice, which can still be seen today to the north of Prace. Fast-moving columns of soldiers on both sides ascended the plateau’s steep slopes. Bernadotte had a significant impact on the Russian Guard while Murat won the cavalry battle for the alliance. A retreat in front of his cavalry was inevitable after he had pushed back and chased the infantry. It was at this point that the French emperor ordered his own Guard to interfere, giving his mamelukes the edge they needed to overcome Tsar Alexander’s regiment of knights-guards.

The outcome of the conflict was decided before midday. Kutuzov was out of options; the army corps of Lannes and the cavalry of Murat had massively assaulted Bagration, who was supposed to launch diversionary operations to lure French attention away from their right side. Despite this, he withdrew in excellent order down the Brünn-Olmutz route, via which Tsar Alexander, Emperor François, and their respective staffs would depart the battlefield at 1 p.m., with all hope gone. Only Kutuzov will stay behind to salvage what can be salvaged.

The coalition’s condition was not improving in the south of the battlefield. As with the northern “pincer,” the soldiers tasked with retaking the Pratzen plateau were unsuccessful. Prior to encountering the French, they encountered a traffic bottleneck caused by their own late-arriving or escaping colleagues from the onslaught on Telnitz and Sokolnitz or the fight for Pratzen. If they survived being mowed down by the grapeshot that Soult’s guns spewed with redoubled strokes, they were smashed by the salvos of the French infantry’s muskets. The Austro-Russians knew, after only one setback, that they were squandering their efforts and the lives of their soldiers.

To seal the victory, Napoleon gave the order for Soult to push south at about 2:00 p.m., crushing what remained of the coalition’s left flank and cutting off their final retreat. The two surviving columns, led by Andrault de Langeron and Dokhtorov, had been badly crushed after the vanguard was almost wiped out in the combat around Telnitz. After an hour and a half, they were just a confused mob of refugees hoping to reach safety in the marshes and frozen ponds.

It was expected that the French would keep control of several thousand of them. The destiny of Others after Austerlitz will be far less desirable. The historic banks of the frozen pond of Satschan may still be seen today at Satcany; it was here that a renowned but controversial occurrence occurred during the disaster. As the French artillery opened up, the ice cracked and engulfed hundreds of guns and the horses that pulled them.

The exact number of dead troops was unclear, but it seems that the figure has been considerably inflated since the incident. Some estimates put the death toll at several thousand. A few days later, the French had the pond drained in order to recover the cannons, which, along with the other pieces captured that day, provided the bronze that constitutes the Vendôme column in Paris today. However, it was unclear whether or not additional bodies had already been recovered and buried before the French arrived.

Aftermath of the Battle of Austerlitz

In the late hours of December 2, 1805, the last large coalition force effectively vanished. On the one-year anniversary of his coronation, Napoleon Bonaparte had another reason to celebrate: the realization that he had finally won the decisive battle he had been seeking at Austerlitz, thanks to his skill as a strategist and tactician. On December 26, effectively ending the War of the Third Coalition, the Treaty of Presburg was signed. A dishonorable peace that would cost Francis II territory, a massive war indemnity, the title of Germanic Emperor, and the birth of a “Confederation of the Rhine” founded on the ruins of the Holy Empire.

However, the roots for the subsequent coalitions were sown during this period of peace: in 1806, an embarrassed Prussia joined Russia and England in an effort to break France’s grip on Germany; and in 1809, Austria attempted, but failed, to exact vengeance on Russia and England.

References

- Castle, Ian. Austerlitz: Napoleon and the Eagles of Europe. Pen & Sword Books, 2005. ISBN 1-84415-171-9.

- Chandler, D. G. (1966). The Campaigns of Napoleon. New York: Simon & Schuster. OCLC 185576578.

- Mikaberidze, A. (2005). Russian Officer Corps of the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. New York: Savas Beatie. ISBN 978-1-61121-002-6.

- Uffindell, Andrew (2003). Great Generals of the Napoleonic Wars. Kent: Spellmount Ltd. ISBN 1-86227-177-1.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. 1990). Understanding Defeat: How to Recover from Loss in Battle to Gain Victory in War. Paragon House. ISBN 1-5577-8099-4.