During the Gallic era, the Aedui were a Celtic people who occupied the region of present-day Burgundy, with Bibracte, located on Mount Beuvray, as their capital. The mention of “our ancestors, the Gauls” often sparks controversy today, and the teaching of their history (and, through them, ours) is frequently caricatured. However, we now know that the Gauls were diverse, both in their structures and their relations with Rome, as well as with one another. This plurality is perhaps one of the rich elements of our “roots.” The Aedui were one such people, unique in many ways, particularly in their interactions with Rome.

Geography and Territory

Aedui: Celts, “Brothers” of Rome

The Gauls were part of the Celtic people who originated from Central and Eastern Europe and settled in what would become Gaul around the 6th century BCE. Little is known about them until the 2nd century BCE, when the “civilization of oppida” (singular: oppidum) developed. The Aedui were a good example of this, establishing themselves in what Caesar referred to in “The Gallic Wars” as cities, and primarily becoming an economic and commercial power.

While oppida were fortified places, they were above all major economic and cultural centers, well-connected by transport routes and always located near raw material deposits. The oppida of Bibracte (135 hectares) and Alesia (97 hectares) demonstrate the importance of these places, far from the disorganized barbarian image typically associated with the Gauls.

The history between the Aedui and Rome begins around 120 BCE when the Romans defeated the Arvernian king Bituitus, ending Arvernian dominance over the peoples of future Gaul. The Aedui benefited most from this and quickly aligned with Rome through trade and military agreements.

While the exact details of this alliance remain unclear, Latin authors such as Tacitus tell us it was very strong; indeed, the Aedui were referred to as “fratres consanguineique populi romani” (brothers and kinsmen of the Roman people), a title previously only granted to the Trojans (the people of Aeneas, founder of Rome).

The relationship between the Aedui and Rome was therefore very strong, particularly on the economic front, which was advantageous for the Roman Republic to have allies in such a strategic location. It’s no surprise then that when the Aedui called on Rome for help in 58 BCE against the Helvetian threat, a certain Julius Caesar came to their aid.

Bibracte and the Gallic Wars

At that time, Caesar was the governor of Cisalpine Gaul and used this opportunity to assist the Aedui as a means to establish his presence. Though not called a conquest, it had begun. The Aedui were divided on how to respond to Caesar’s actions. He met with the three main leaders based in Bibracte, their capital. Liscos, the supreme Aedui magistrate, opposed Dumnorix, accusing him of betraying Rome. Dumnorix was a wealthy nobleman with his own cavalry and harbored ambitions for a more independent Aedui nation.

Diviciacus, Dumnorix’s brother, was “the most respected of the Aedui,” a member of the druidic college, and had personally traveled to Rome to request Senate assistance against the Sequani and Arverni (unsuccessfully). He repeated his plea directly to Caesar to drive out the Germanic forces of Ariovistus. This time, it worked, but the Aedui became even more dependent on Caesar’s legions, whom they had to support and supply. Dissent grew, and Dumnorix took advantage by refusing to accompany Caesar to Britain in 54 BCE. Caesar, less patient this time, had the Gallic leader caught and executed. Legend says that Dumnorix cried out for his freedom and that of his people before his death. Around the same time, Diviciacus “disappeared.”

The revolt against Roman occupation was brewing across Gaul, leading to the uprising led by Vercingetorix, the Arvernian. But the Aedui were caught between a relative “Gallic solidarity” among peoples who had long been at war and their logical interests aligned with Rome. They chose not to engage while avoiding helping the Romans. Caesar, however, pressured the Aedui, exploiting their internal divisions by backing Convictolitavis, who placed Litaviccos in charge of the Aedui army tasked with supporting the Roman legions.

On the way to Gergovia, Litaviccos turned against the Romans, pillaging the supply convoy and fleeing. Caesar managed to recapture his troops, while the Gallic leader reached Gergovia alone. But after being repelled from Gergovia, Caesar had to deal with a rebellion from the Aedui as he planned to retreat to Bibracte. The rebellion was led by Eporédorix. At this point, the Aedui had finally chosen the Gallic side. An assembly was convened in Bibracte, and Vercingetorix was elected leader of the Gauls near the Wivre Stone.

Little is known about the Aedui’s participation in the remainder of the Gallic Wars. Caesar did not attack Bibracte, the center of the rebellion, and eventually defeated Vercingetorix at Alesia. However, Caesar, now aware of the Aedui’s fickleness, decided to station his troops in Bibracte, where he wrote his “Commentaries” during the winter of 52 BCE.

From Bibracte to Autun: The Romanization of the Aedui

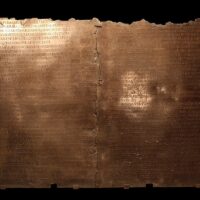

As seen, Bibracte was an oppidum, the “capital” of the Aedui and a significant economic and cultural hub. Its fortifications, especially the “murus gallicus” reconstructed at the Rebout Gate, highlight its importance. Excavations have shown that the city was organized by districts over an area of 135 hectares. Metalworking seemed to be a specialty of Bibracte, as evidenced by numerous workshops and nearby mines. One of Bibracte’s mysteries is the famous basin, made from Mediterranean materials. Its function is unknown, constructed according to Pythagorean geometry. It may have been religious or marked the city’s center.

Despite Bibracte’s importance, it began to lose influence by the end of the Republic, gradually becoming deserted. This decline wasn’t due to Roman repression, as Caesar quickly forgave them, needing Aedui support. Perhaps the peace that followed the civil wars led Rome to move the Aedui capital to a more accessible location in the plains: the founding of Augustodunum (Autun) occurred around 16-13 BCE.

Unlike Bibracte, Autun was a true “Roman city,” both in its construction and institutions. It quickly became an important economic and cultural center, and the Aedui regained their privileged status with Rome. Thus, the city served as a showcase and starting point for the Romanization of the vast region under its control. However, Autun’s history was not always smooth. Under Tiberius (14-37 CE), some of its privileges were revoked, sparking a quickly quashed revolt.

Later, Emperor Claudius (41-54 CE) proposed to the Roman Senate that Gauls, including the Aedui, be admitted. They were the first among the Gauls to do so.

After the death of Nero in 68 CE, the Aedui supported Galba and then Vitellius.

For nearly two centuries, Autun and the Aedui vanish from historical sources until they reappear during the events leading to the creation of the Gallic Empire. Rome was in crisis, besieged by barbarian invasions, and Autun was sacked by the Alemanni in 259 CE.