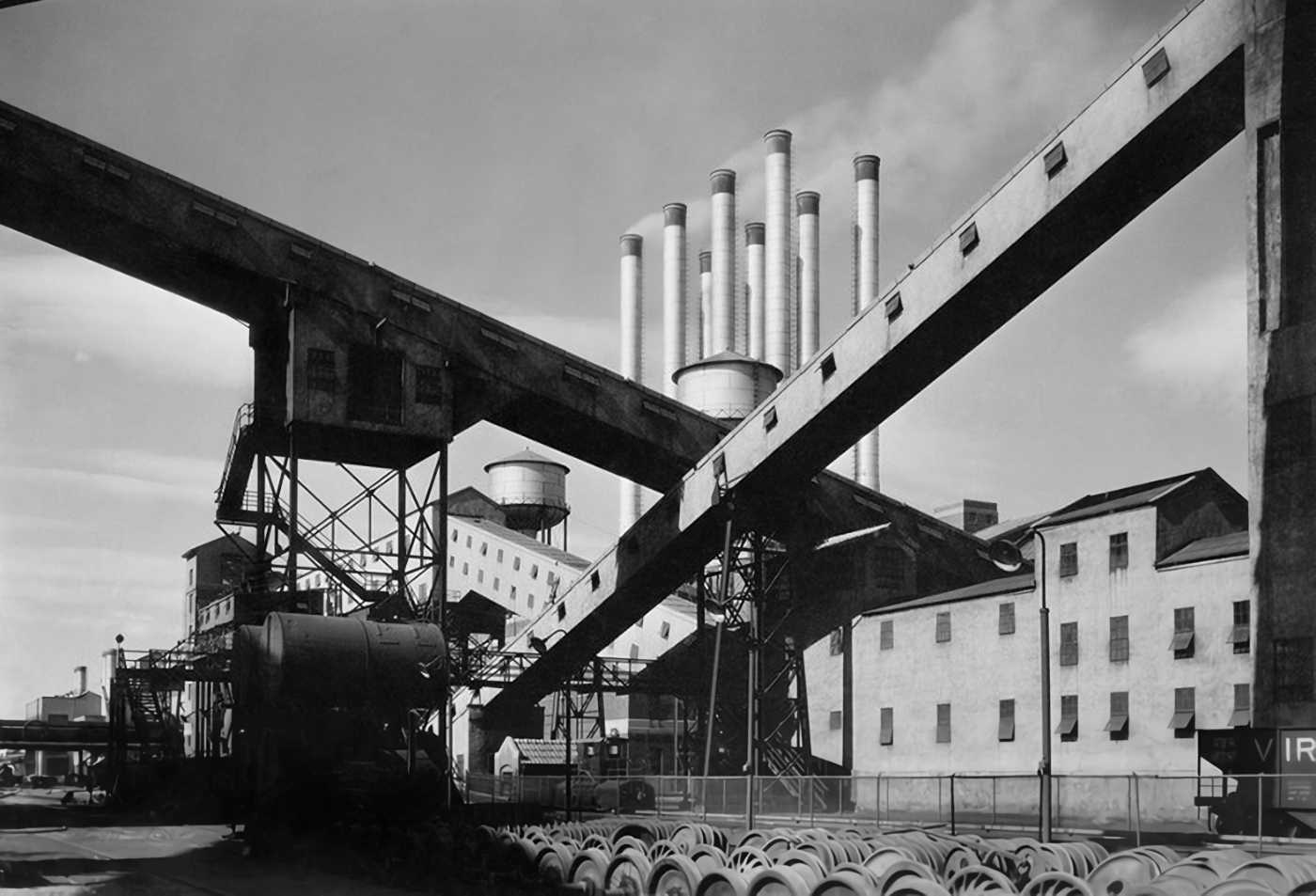

How Albert Kahn built Detroit, the industrial superpower of its time

Until the middle of the 20th century, Albert Kahn's Detroit was the most significant industrial metropolis in the world. The son of immigrants from Germany constructed buildings with an efficiency reminiscent of the production line. However, "his" city declined just as rapidly as it had developed.