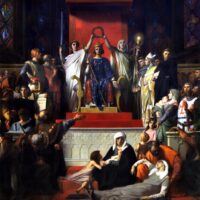

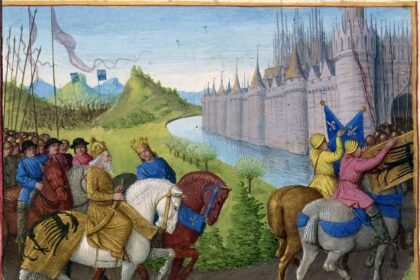

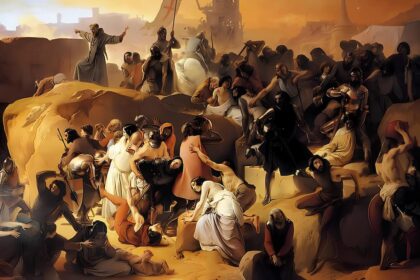

Albigensian Crusade: The Battle Against Cathar Heresy in Southern France

The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) was a military campaign initiated by the Catholic Church to eradicate the Cathar heresy in the south of France, particularly in the region of Languedoc.