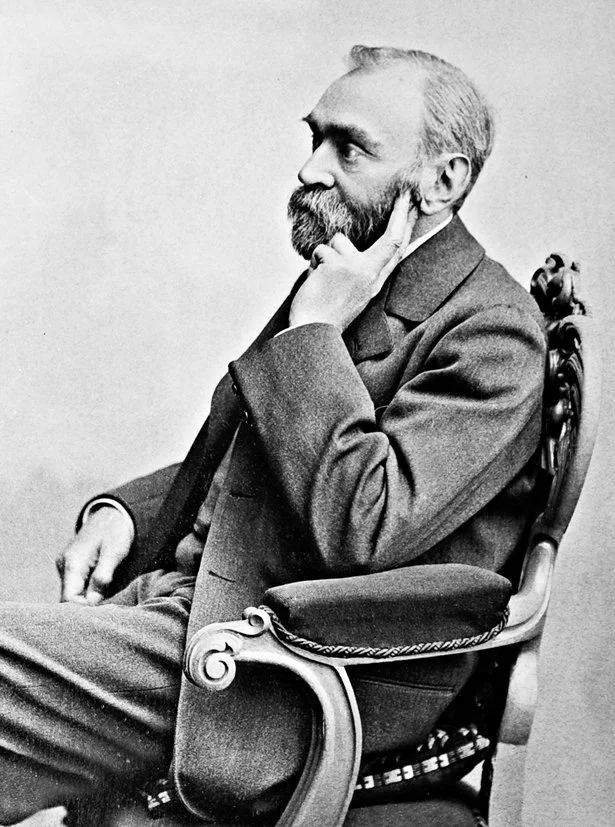

In modern times, Alfred Bernhard Nobel (1833-1896) is remembered mostly as the man who established the Nobel Prizes, widely regarded as the most prestigious scientific honor. However, who was Alfred Nobel in the first place? How did the man who discovered dynamite end up giving his money to promote world peace and science?

The invention of dynamite, which has practical and lethal applications, launched Alfred Nobel’s career and made him wealthy. By using it, Nobel was able to convert nitroglycerin, a very dangerous explosive, into a more manageable and portable form for the first time. The invention of dynamite made possible the completion of the Gotthard Tunnel, one of the world’s most complex and challenging engineering projects. However, Alfred Nobel’s discovery was not without flaws. Rapidly becoming a dangerous weapon due to its explosive potential.

Success in selling his “Nobel’s Safety Powder” brought Nobel a wealth, which he used to create the Nobel Prize in order to recognize those who have made significant contributions to humankind. Every time the Nobel Prizes are handed out, the scientific community takes a moment to reflect on the life and legacy of its namesake, the brilliant scientist and businessman Alfred Nobel.

The apprenticeship years

On October 21, 1833, into a family of engineers, Alfred Nobel was born in Stockholm. However, the Nobel family only remained in Sweden for a brief time after the birth of their son. They eventually settled in St. Petersburg. They lost everything in the construction business and decided to start again in Russia, where they had more luck.

Father Immanuel quickly established his own engineering works and foundry, eventually hiring over a thousand people at once. He had a prodigious capacity for innovation, which he put to good use by rapidly creating new devices, particularly for use in battle. Immanuel Nobel and his family prospered as a result of the company’s success and the Tsar’s court’s approval.

Traveling from lab to lab for research purposes

The thriving firm made it possible for Alfred and his brothers to have a solid education. The boys’ private teachers had them proficient in Russian, English, French, and German in addition to Swedish. In fact, Alfred considered taking up writing since he had such a deep and abiding love for reading.

While music was his first love, technology and chemistry were close seconds, and his father’s enthusiasm for the latter was a major influence. He immediately began to provide the young kid with specialized instruction, with an initial concentration on the discipline of chemistry. As early as age 17, he sent young Alfred on a two-year educational excursion around the United States, Germany, and France. The first trip was to the Parisian labs of the famous scientist Théophile-Jules Pelouze.

An unforgettable run-in

Here, Alfred Nobel met the Italian Ascanio Sobrero, an important person on his journey toward the big discovery that would make him renowned. The scientist had created nitroglycerin, the first liquid explosive, a few years previously. Sobrero’s face was badly injured in the explosion caused by mixing glycerin, sulfuric acid, and nitric acid. It seemed the explosive was too risky to be used in any meaningful way.

Upon hearing about nitroglycerin for the first time, Nobel thought about how it might be better managed, even back in Paris. However, when he got back to St. Petersburg in 1852, this wasn’t a factor at first. Nobel had a lot on his plate at the family company during the following four years. The development of armaments during the Crimean War resulted in huge revenues for the “Fonderies & Ateliers Mécaniques Nobel & Fils.”

Nitroglycerine to the rescue!

But the success story has a tragic twist: the conclusion of the war meant that no further orders would be coming in. They ran into some money problems as a family. They had been on the edge of financial ruin and had returned to Sweden by 1859. In light of the current economic crisis, Alfred Nobel’s chemistry instructor highlighted the substance’s unrealized potential.

The choice was made quickly: Nobel intended to take on what Sorbrero did not, out of fear of the deadly potential of his invention. He hoped that by making the explosion marketable, he could save his loved ones from their dire situation.

An innovation with potential to explode

In Stockholm, Alfred Nobel, together with his father Immanuel and brother Oskar-Emil, launched a family company based on nitroglycerin experimentation. It’s hardly surprising that handling such a potentially dangerous material was a difficult job. The Nobel family, however, had their first taste of success in 1861 when they successfully mass-produced their “explosive oil.”

The fundamental issue, however, still stood: The metastable material could explode from even little vibrations or impacts. Therefore, it was exceedingly dangerous to transport it using standard methods such as freight trains or horse and cart. In addition, a fuse could not be used to set off the liquid as easily as it would with black powder.

A sparking concept

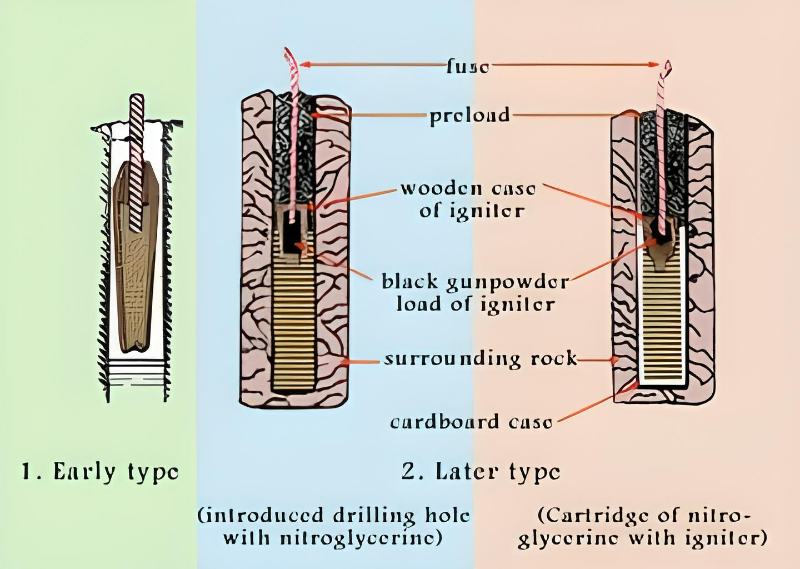

To detonate, nitroglycerin just needed a quick spark. However, how would one safely set off such a massive explosion? As the explosion was about to fizzle out, Nobel had an idea that set it off. He created a tiny container, filled it with black powder and nitroglycerin, and hanged it in a blast hole.

Nobel devised the first ignition, a chemical that could be exploded with a fuse and then causes the nitroglycerin underneath it to explode due to the pressure wave created. His first description of his package was a “patent detonator.” Subsequently, he reformulated the device to utilize fulminated mercury instead of black powder and dubbed it a detonator.

What a horrible accident

The sensitivity of nitroglycerine to impact persisted, though. Nobel learned the hard way just how hazardous this characteristic could be. On a morning in September 1864, a tremendous explosion jolted those living in the southern part of Stockholm. A laboratory facility on the Nobel estate that housed 125 kilos of the explosive went off the rails. Five individuals, including Nobel’s younger brother, were killed in the explosion.

Nobel eventually perfected a method of using kieselguhr, a kind of diatomaceous earth, to stabilize dynamite. Even after the horrific catastrophe, the scientist worked relentlessly to advance his field and eventually extended it to Germany. The mining industry was growing, and new railroad lines were being built rapidly, creating ideal circumstances for the marketing of Nobel’s explosive oil.

The long-awaited breakthrough

Nobel constructed an industrial facility in Krümmel’s Geesthacht neighborhood despite the lack of a satisfactory answer to the transportation issue. However, in May of 1866, a horrific explosion took place there, as well. Not long ago, a vessel off the coast of Panama carrying the deadly cargo exploded. Public opinion and legislative pressure were rising. The nitroglycerine’s destructive potential must be brought under control.

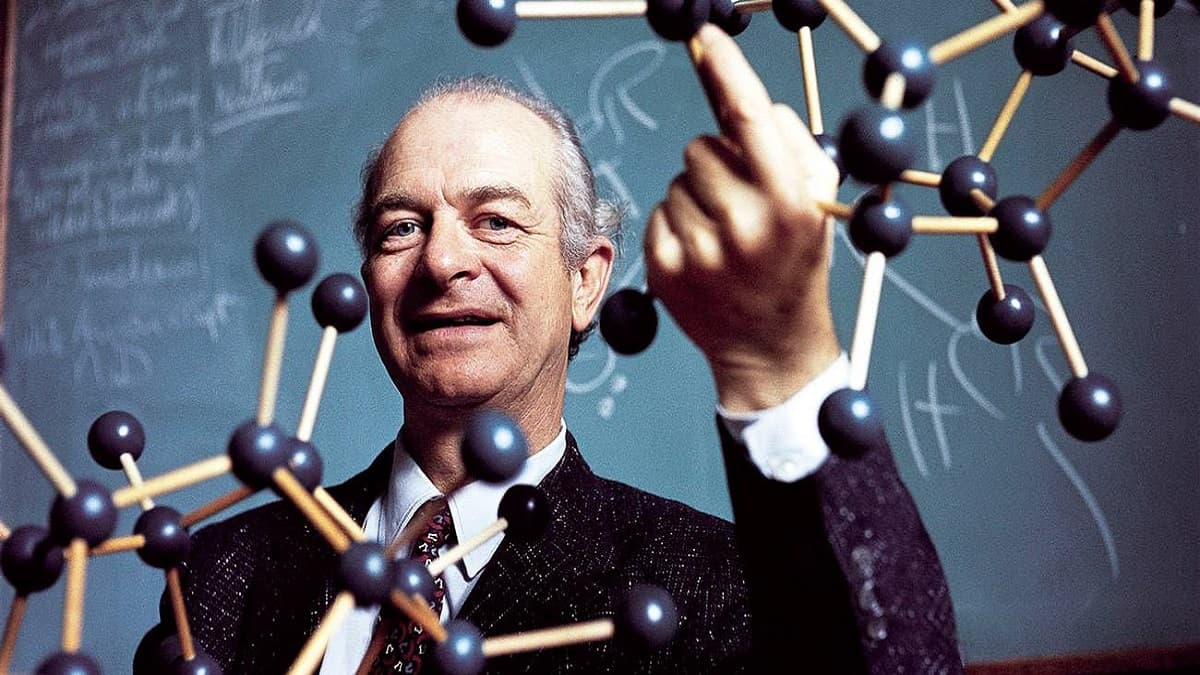

During the same time period, Alfred Nobel made a groundbreaking discovery. He discovered that by combining nitroglycerin with diatomaceous earth, a powder derived from the shells of microscopic sea animals, the liquid could be shaped into a manageable bulk and carried with relative ease. Some say he made the finding by sheer happenstance. However, Alfred Nobel himself denied these claims.

From dynamite to explosive gelatin

To be sure, in 1867, Nobel sought patents in several countries on his new explosive, which he termed dynamite (from the Greek for “power”). An enormous amount of money was made from the new material. However, Nobel was not content just yet. With the addition of diatomaceous earth, he succeeded in making nitroglycerin less dangerous. However, it was now only about five times as potent as black powder and had lost part of its explosive strength over time.

In 1876, Nobel developed a workable alternative to diatomaceous earth by combining nitroglycerin with collodion wool. As a consequence, they came up with blasting gelatine, a dynamite explosive that was both stable under pressure and highly explosive. This improved variant of the original dynamite remained one of the most potent commercial explosives available today.

Progress and death hand in hand with Nobel’s dynamite

Black powder has been the sole kind of explosive known to mankind for almost a thousand years. However, the material is not powerful enough for widespread explosions. Explosives like Nobel’s dynamite ushered in a new age since they were the first chemicals to significantly outperform black powder while being relatively safe to use (though mishaps using dynamite are unfortunately common).

Shortly after its introduction, Nobel’s invention quickly became the most popular explosive in the world. Tunnels, canals, and mines could all be carved out of the earth with its aid. With the advent of dynamite, construction workers could finally realize their wildest dreams.

1 million pounds (lbs) of dynamite used in a tunnel construction

Major projects, like the 15-kilometer Gotthard Tunnel that snaked its way through the summits of the same-named mountain range in Switzerland, demonstrated the efficacy of the new explosives. Engineers drilled into the mountain to a depth of around a meter before using dynamite for blasting. Construction of the Panama Canal also made use of the explosive.

However, the invention of dynamite resulted in not only a powerful industrial explosive but also a terrifying weapon. The brutal use of dynamite dates back to the Franco-Prussian War, long before Alfred Nobel improved his explosive by combining it with blasting gelatine to make it even more destructive.

Lethal instrument

In addition, dynamite was crucial to a wave of terrorist assaults that swept over Europe at the close of the 19th century. So many working-class revolutionaries and anarchists used dynamite to strike the ruling class and wreak widespread destruction.

The Russian Tsar Alexander II was their most recognizable victim. While on a carriage trip through St. Petersburg, he was murdered by a dynamite device. After that, many European countries restricted access to dynamite and other explosives due to widespread abuse of the substance.

In 1884, for instance, the German Reich discoureged the “criminal and murderous use of explosives” by passing the so-called Dynamite Law. Despite Nobel’s best intentions, his technology was increasingly being put to lethal use. His creation was a mixed gift and a curse.

The Nobel Prize

Alfred Nobel made a fortune and left a legacy by commercializing his innovation on a global scale. The name of the Swedish scientist and businessman was still widely connected with more than just dynamite. His enduring financial legacy was also a perennial newsmaker. After all, it’s the basis for the Nobel Prize, the highest honor in the scientific and social fields.

Acts of generosity

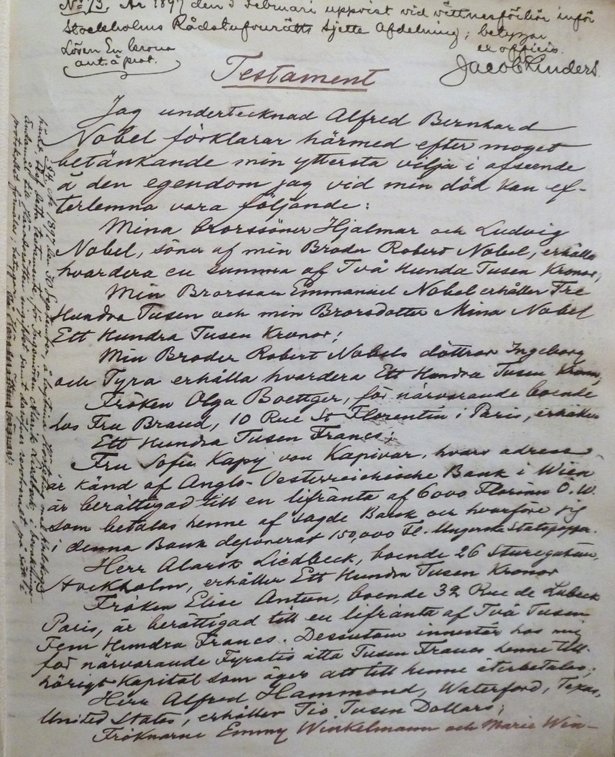

Nobel, who died childless in 1895, left most of his riches (around 31 million Swedish crowns) to a fund in his testament. The inventor stipulated in his will that the interest accrued be split into five equal parts and “given as rewards to those who have made the greatest contribution to humanity in the last year.”

The prize would be awarded for exceptional work in physics and chemistry, the two scientific disciplines that inspired Alfred Nobel’s idea. The scientist, on the other hand, also saw medicine as a legitimate academic field. Additionally, Alfred Nobel, who wrote numerous short stories and poems himself, included an award for literature in his testament. Also, the fifth portion of the award was meant to recognize “the person who shall have done the most or the best work for fraternity between nations.”

Winners of the very first Nobel Prizes

After Nobel’s death on December 10, 1896, his will was finalized three and a half years later. The proposal for the Nobel Foundation’s founding laws was approved by the Swedish Government in June 1900. Once the five months passed, the management of the foundation assumed charge of the money. The first Nobel Prize was given out on the fifth anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death.

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen, who discovered the radiation we now know as X-rays, was awarded the first Nobel Prize in Physics. Both Dutchman Jacobus van ‘t Hoff, who discovered the rules of chemical dynamics and osmotic pressure in solutions, and German military doctor Emil von Behring, who discovered a treatment for diphtheria, won the first prizes in the Nobel chemistry category. Frédéric Passy, known across the globe as the “Apostle of Peace,” and humanist Henry Dunant will forever be remembered as the first recipients of the Nobel Prizes in Literature and Peace, respectively.

Every year on the anniversary of death

Others followed in their footsteps as Nobel laureates. With the exception of a few years, particularly during times of war, when the award was not presented, the Nobel laureates are announced annually around the beginning of October, and the Nobel Prizes are awarded on December 10. The award money is still paid out of the interest and revenue from the inventor of dynamite’s inheritance. Each winner gets eight million Swedish kronor (now equivalent to roughly 700,000 dollars).

“Merchant of death” or advocate for world peace?

There was widespread surprise when news of Alfred Nobel’s donation of a peace award emerged after his death. After all, people tended to identify the name “Nobel” with explosives and other advances that could be used in conflict, but not with nonviolent causes. In fact, in an erroneous obituary, journalists even referred to the scientist as a “merchant of death.”

Is it possible that the scientist had mixed feelings about the impact of his work in the armaments business, and that he hoped to use the money from the award to atone for the “evil side” of his inventions? It’s impossible to know for sure from where we stand now. It is evident, however, that Alfred Nobel was essentially running in parallel on issues of war and peace throughout his lifetime.

Deadly inventions

However, he seemed endowed with a lifelong fascination with the science of guns and explosives. His father was also an engineer with a deep interest in this field; he helped create rapid-fire guns and naval mines used in the Crimean War. Dynamite, Nobel’s own great innovation, was also used in war despite its original intention.

And it wasn’t only dynamite; far into his senior years, the brilliant scientist continued to work on a wide range of technologies with the potential to be used as weapons. A patent applicant, he sought protection for a wide range of armaments, including rockets, cannons, and novel formulations of gunpowder.

Alfred Nobel, the war resister

In contrast, Nobel cared deeply about topics related to world peace. Thus, he became quite close with the pacifist Bertha von Suttner via letters. At the tail end of the nineteenth century, the Austrian was one of the primary proponents of the peace movement that was gaining momentum throughout Europe.

Inspired by her, Nobel became a member of the Austrian Peace Society and donated money to its cause. It is likely that von Suttner was also responsible for the rich businessman’s decision to endow a peace award with a portion of his estate.

Alfred Nobel does not seem to find any inconsistency between his work in the arms business and his desire to promote world peace. Instead, he seems to subscribe to the view, widespread in the 19th century, that a scientist is not responsible for the application of his research.

Each new scientific finding, in this perspective, is apolitical at first, but has the potential to be used for either good or evil. Alfred Nobel had a similar nave belief in the possibility of good coming from his arsenal of explosive weapons. In 1963, the “Nobelium” element was named for Alfred Nobel.

Military for peace

His letter to von Suttner from 1891 reads, “Perhaps my factories can put an end to the conflict quicker than your peace congresses: On the day when two armies can annihilate one other within seconds, all civilized countries will undoubtedly withdraw their forces, overwhelmed with horror.”

In Nobel’s view, only the military might can guarantee lasting peace. He believed that with the appropriate weapon, the idea of deterrence might one day render conflicts inconceivable. Since he passed away so soon, he never got to see the First World War or realize how wrong he was.

Bibliography

- “Alfred Nobel’s Will”. The Norwegian Nobel Committee.

- “Alfred Nobel’s life and work”. NobelPrize.org.

- “Nobelium”. Royal Society of Chemistry.

- “Alfred Nobel’s Fortune”. The Norwegian Nobel Committee.