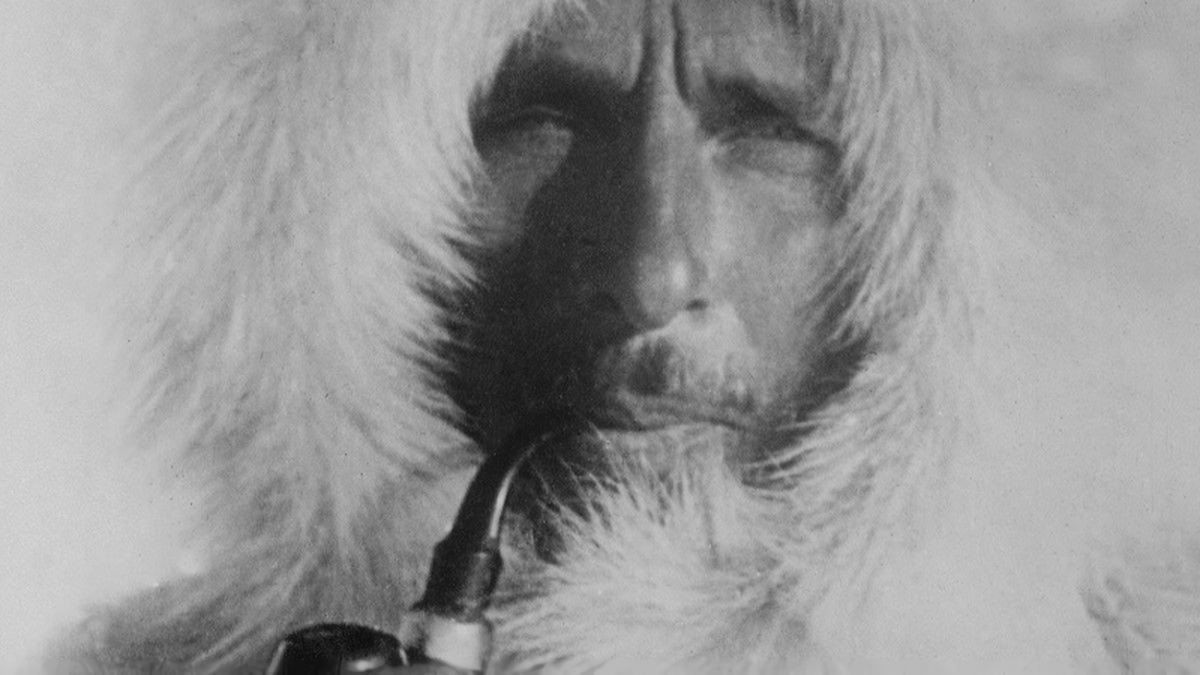

Alfred Wegener (Alfred Lothar Wegener) was recognized for two very different successes in his life: Arctic climate research and the theory of continental drift. However, according to him, these two initiatives were very reasonable efforts due to his passionate interest in climate studies. Wegener was born on November 1, 1880, in Berlin. During his education, he focused primarily on astronomy, then on meteorology and climate science.

In 1905, he became a meteorological observer at the Urania Observatory near Berlin; in 1909, he started teaching at the University of Marburg and taught astronomy and atmospheric physics. In 1924, Wegener received a long-desired professorship offer from the University of Graz, Austria. Until that time, he had already attracted some attention and raised some doubts with his theory of how the great land masses of the Earth came about.

Alfred Wegener’s Continental Drift Theory

He started his first research in Greenland in 1906, when he was invited as a climate scientist and glaciologist to a Danish expedition led by Ludvig Mylius-Erichsen. In 1912, he again went to Greenland on a Danish expedition, during which time he became one of the first people to cross Greenland from east to west with his dog sled. These expeditions boosted Wegener’s reputation in Europe, especially in Denmark and Germany.

Alfred Wegener consulted with leading climate scientist Wladimir Köppen while planning the Greenland expeditions. Meanwhile, Köppen was working on the classification of the world’s climates. In 1913, he married Köppen’s daughter, Else. Köppen was more experienced at the time, so he mentored Wegener. However, the two soon began working together in research on paleoclimate, which is based on geological and paleontological evidence, such as coal deposits, salt deposits, plant and animal fossils, and glaciers. The idea of the continental drift theory emerged here.

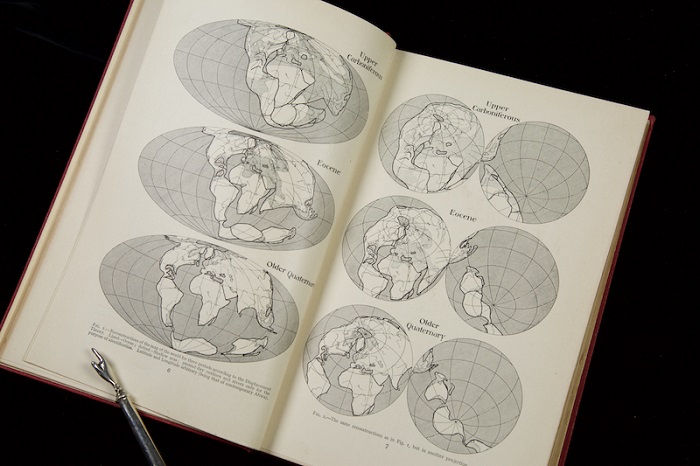

Alfred Wegener first found some identical fossils on both sides of the ocean. Moreover, he saw the same phenomenon in the geological formations that started in Africa and continued in South America. Geologists were already aware of these cases. They put forward the theory that plants and animals migrated between continents through land bridges that are not available now. But Wegener was developing an alternative theory. He compared the shores of every continent and realized how they fit against each other like jigsaw puzzle pieces, and he stated that these geological features have become an ongoing pattern. From this point on, he began to focus on the idea of continental drift and tirelessly looked for geological and paleontological evidence to test his hypothesis.

If we are to believe Wegener’s hypothesis, we must forget everything that has been learned in the last 70 years and start all over again.

R. T. Chamberlin, University of Chicago, 1928,

In 1915, he published “The Origin of Continents and Oceans.” In this book, he argued that all the continents were interconnected into a massive land mass, which he called “Pangaea,” meaning “Urkontinent” or “All-Lands” in Greek. Pangaea gradually disintegrated, and the continents shifted to their current positions. The Continental Drift Theory was taking shape.

Arguments Against Wegener’s Theory

Alfred Wegener’s book sparked a storm of controversy among geologists over the flaws in the theory. The quarrels reached a global dimension after the book was translated into English. Two international conferences were held to discuss the continental drift theory, one in London in 1923 and the other in New York in 1926. Wegener did not attend any of these conferences.

Geologists at the London conference found haunting geological deficiencies in Wegener’s supporting evidence. They stated that the geological mapping, which supported the claim that the continents were interconnected, was insufficient. All those who stood against the theory rejected the proposal that the tides and the Earth’s rotation could provide the force to move the continents. The English geologist Philip Lake was among the critics of Wegener and outspokenly said, “He is deaf to every argument.” The distinguished mathematician and geophysicist Harold Jeffreys said, “It is out of the question,” stating that there could be no force strong enough to move the continents.

The North American Conference was particularly unpleasant. Because the concept of uniformity had occupied a strong place in the indoctrination of American geologists, the philosophy that was created by James Hutton and others at the end of the 18th century states that the existing natural laws and processes are always present and functioning unchanged. The continental drift theory was concluded not to be an ongoing process, and the argument was rejected. But only a few people found the idea of land bridges irrational and questioned the lack of evidence. In short, a new paradigm was desperately needed.

Mockery of the Continental Drift Theory

The main factor preventing Wegener’s theory from being supported was the lack of information on that great force pushing the continents onto the earth’s crust. However, several geophysicists have come up with the idea that a flow force might be produced that can move fixed continents over time. Wegener agreed with the idea that convection currents in the earth’s crust could move the continents in the fourth edition of his book that had been changed.

As the distinguished geologists openly rejected Alfred Wegener’s theory, the other geologists also comfortably criticized his idea. The idea of continental drift had become the subject of sarcastic jokes: “Half of a fossil was found in America and the other half in Europe.” Many geologists were looking at Wegener as if he were crazy. Still, few geologists and biologists liked the idea of moving continents. Because this could answer many unanswered questions, yet there was still a lack of evidence for the movement.

Although Wegener was disappointed at being rejected, he was still approaching every criticism with resistance and determination, assuming that people saw only part of the picture. He wrote in the 4th edition of his book: “Scientists still do not appear to understand sufficiently that all earth sciences must contribute evidence toward unveiling the state of our planet in earlier times, and that the truth of the matter can only be reached by combining all this evidence.” He never stopped compiling new findings and evidence from many different disciplines to answer criticism later in his book. By the fourth edition, Wegener’s book was really thick.

The Greenland budget: $125,000

The theory of continental drift remained idle for forty years after the American conference, that is, for thirty-odd years after the death of Alfred Wegener. Until the mapping of the earth’s sea beds by using new tools and plenty of state funds in the 1960s, with the encouragement of the Cold War. These new efforts would demonstrate the seabed’s expansion and eventually produce a lot of evidence supporting concepts such as convection currents and plate tectonics in the earth’s crust.

Alfred Wegener turned his attention to Greenland’s climate in the last two years of his life. A German research fund committee set up to fund valuable researchers in the wicked economy of the 1920s supported Wegener for a modest project to explore the Greenland climate. Due to Greenland’s impact on the European climate and its location on possible air routes between Europe and North America, this support was an important matter in those days.

Wegener then saw an unexpected opportunity. He proposed to the committee to expand the aid to a much larger project that would include glacial investigations as well as observing the climate with three stations to be installed in Greenland. Glacier surveys would include measurements of the ice accumulation rate. His proposal required 500,000 German marks (45,000 marks or 125,000 USD at 1929 exchange rates). This was a huge amount at the time. The committee accepted the proposal rapidly, and it was an indication of its great respect for Wegener.

Alfred Wegener’s death

In the summer of 1929, Wegener took his lead assistant on his expedition to select a location on the west coast of Greenland suitable for transporting tools and materials to the upper glaciers. In the spring of 1930, the recruited ship of 20 men from Germany arrived with two propeller sleds, tons of food, and tools.

They experienced a six-week delay in unloading the cargo due to the late breaking of the ice in the Kamarujuk Fjord. They worked throughout the summer to compensate for the lost time and to establish the manned station they named Eismitte (Mid-Ice) in the middle of Greenland. Bad weather and hardware malfunctions did not allow them to fully prepare the central station. The two men dug a multi-room ice cave in Eismitte and settled here to wait for the preparations to be completed. Some essential equipment, such as a prefabricated hut and a shortwave radio, never arrived at Eismitte, as well as food and fuel, which were in short supply.

When the winter storms started in September, Wegener wanted to bring food and equipment to Eismitte, 250 miles away, with dog sleds. It was a desperate move. They completed the journey in 40 days, which usually lasts 14 days, due to delays caused by the storm and disagreements with the Eskimos that helped them. Most of the Eskimos refused to cover the entire distance and returned to the west coast. A day after reaching Eismitte, Wegener and the only remaining Eskimo, Rasmus Willumsen, set out to return to the west coast. It was the first day of November 1930, and that was Wegener’s 50th birthday. They never reached the shore. The following summer, a search team found Wegener’s body in a tomb marked by skis. It was estimated that he died of heart failure due to excessive effort. Villumsen was never found.

Wegener was best known for his work in the Arctic when he was healthy, but today he is remembered for his comprehensive understanding of the moving continents. Since many important details were missing, critics of Wegener could never bring a holistic view to the theory of continental drift. However, the movement of the continents has turned into plate tectonics today, and it has become widely accepted.

Bibliography:

- Wegener, Alfred (1 July 1912). “Die Entstehung der Kontinente”. Geologische Rundschau (in German). 3 (4): 276–292. Bibcode:1912GeoRu…3..276W. doi:10.1007/BF02202896. ISSN 1432-1149. S2CID 129316588.

- Wegener, Alfred (1911). Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre [Thermodynamics of the Atmosphere] (in German). Leipzig: Verlag Von Johann Ambrosius Barth. (in German)

- Alexander du Toit (1944). “Tertiary Mammals and Continental Drift”. American Journal of Science. 242 (3): 145-63. Bibcode:1944AmJS..242..145D. doi:10.2475/ajs.242.3.145.

- Köppen, W. & Wegener, A. (1924): Die Klimate der geologischen Vorzeit, Borntraeger Science Publishers. In English as The Climates of the Geological Past (2015).