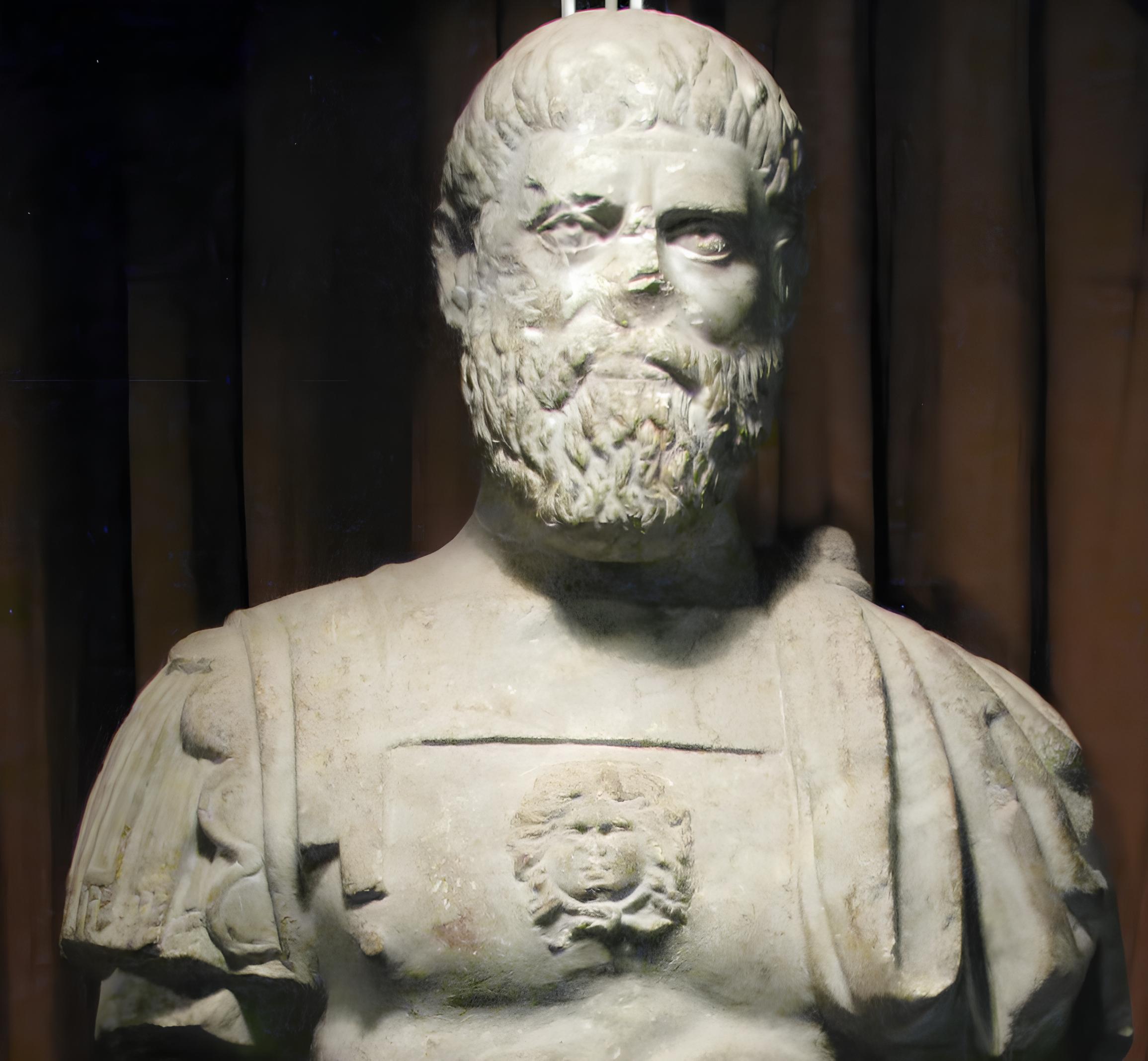

Ammianus Marcellinus: The Military Historian

Ammianus Marcellinus was a Roman soldier and historian of Greek origin. He is best known for his work Res Gestae, which chronicles the history of the Roman Empire from the reign of Nerva (96 AD) to the Battle of Adrianople (378 AD).