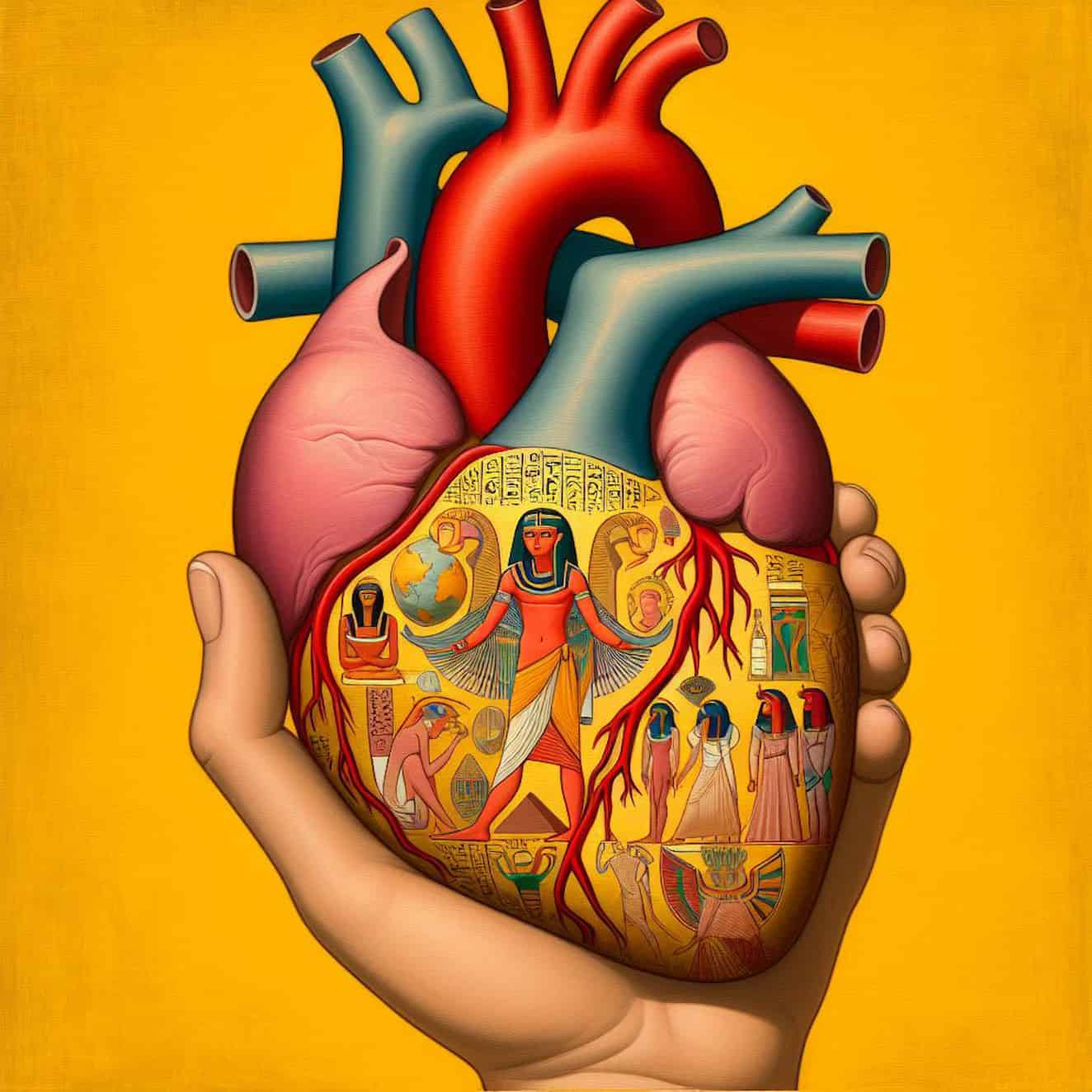

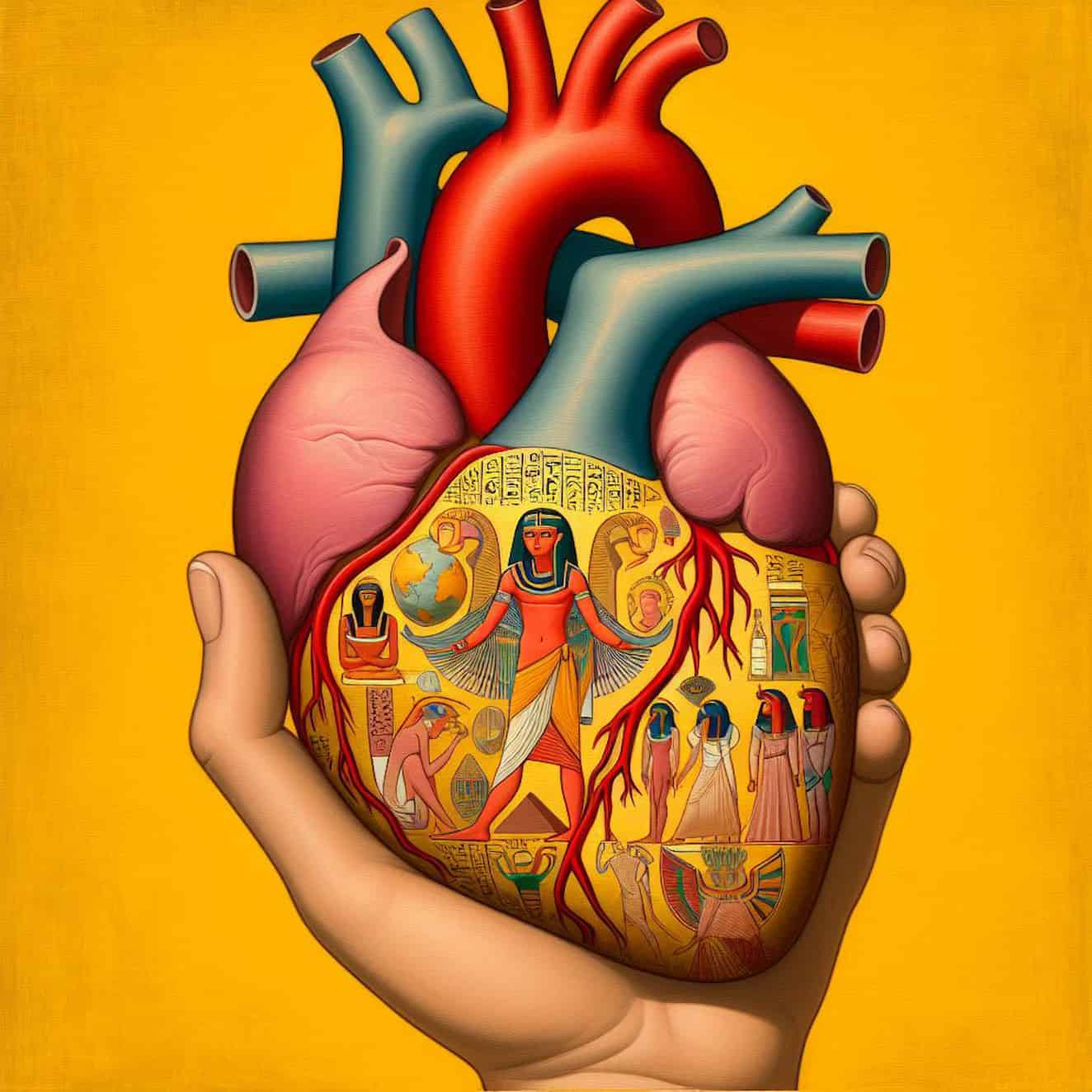

Anatomy of Heart in Ancient Egypt

Cardiology in ancient Egypt was practiced by physicians employing an art understood according to the possibilities of the time and indicated in medical papyri.

Cardiology in ancient Egypt was practiced by physicians employing an art understood according to the possibilities of the time and indicated in medical papyri.