The civilization that originated in ancient Italy and eventually dominated the whole Mediterranean at the expense of Greece and Carthage was called “Ancient Rome.” Starting with Romulus in the 8th century BC and continuing through Marius in the 2nd century BC and the battle between Hannibal Barca and Scipio Africanus, this era was filled with mythological figures and bloody conflict. Beginning with legendary monarchs and moving on to the Etruscan Tarquins, it eventually gave rise to the Roman Republic (510 BC to 27 BC) and its illustrious Senate.

- The founding of the city of Rome

- The founding of the Roman Republic

- Ancient Rome: A divided society

- The beginnings of the Roman expansion

- Rome against Carthage; the fight to the death

- During the Second Punic War

- Supremacy of ancient Rome in the West

- In the affairs of the East

- War in the West

- New internal tensions in Ancient Rome

- Arrival of the Barbarians

- Marian reforms

- The legacy of Attalus

- A city in full glory

- The Social War in Ancient Rome

- The war against Mithridates and the fight between Marius and Sulla

- The Sullanian restoration

- Pompey against pirates

- The first triumvirate and the Gallic Wars

- Caesar against the Senate and Pompey

- The Triumph of Caesar

- The conspiracy and the Ides of March

- The failure of the republican restoration

- Second triumvirate

- Octavian and Antony: Between tension and reconciliation

- The rupture and the beginnings of the Empire

The founding of the city of Rome

The founding of Rome, whose legendary first ruler was named Romulus, is often placed around the period when the Greeks began a genuine exodus in the Mediterranean basin. In Roman mythology, Romulus and his twin brother Remus founded Rome on the site where they had been raised by a she-wolf on April 21, 753 BC. Romulus and the so-called legendary kings took turns at the helm of Rome, and their reigns corresponded to the symbolic functions theorized in the Indo-European tri-functionality.

Romulus and Numa (r. 715–672 BC), the second king of Rome, represented the traditional royalty in a dualistic way, with one side representing the executive power and the other representing the religious function (which the Indo-European kings partially fulfilled), and Tullus Hostilius (r. 672–640 BC), the third king of Rome, represented the political function. In addition to this oral history, archaeology has brought the ancient Roman past to life for us, filling in the gaps where texts are lacking.

The finding of “pole holes” in the wooden huts of the first Romans implies a possible agro-pastoral activity, which is consistent with the lifestyle described by Titus Livius (Livy) about Romulus and proposes a habitat from a period similar to that recounted in the Roman tale. Attestations of the Etruscans’ (astonishing and rather obscure in their origin) existence date back to the 7th century BC, and Etruscan royalty in Rome started in the 6th century with Tarquin the Elder, Servius Tullius, and Tarquin the Superb.

Even if the legitimacy of these Roman kings’ reigns could not be established beyond a reasonable doubt at the time, it was undeniable that Rome was an Etruscan city at the time, as evidenced by the city’s adoption of Etruscan urbanism as represented by the Servian Wall (or wall of Servius Tullius) and the widespread use of other typical Etruscan consumer goods like pottery. The city of Rome was under the domination of the Etruscan king Tarquin the Superb (Lucius Tarquinius Superbus) and the Capitol housed the cult of the divine triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva.

At one point in time, Rome was a mighty metropolis that ruled over all of Latium thanks to the influence of the Latin League.

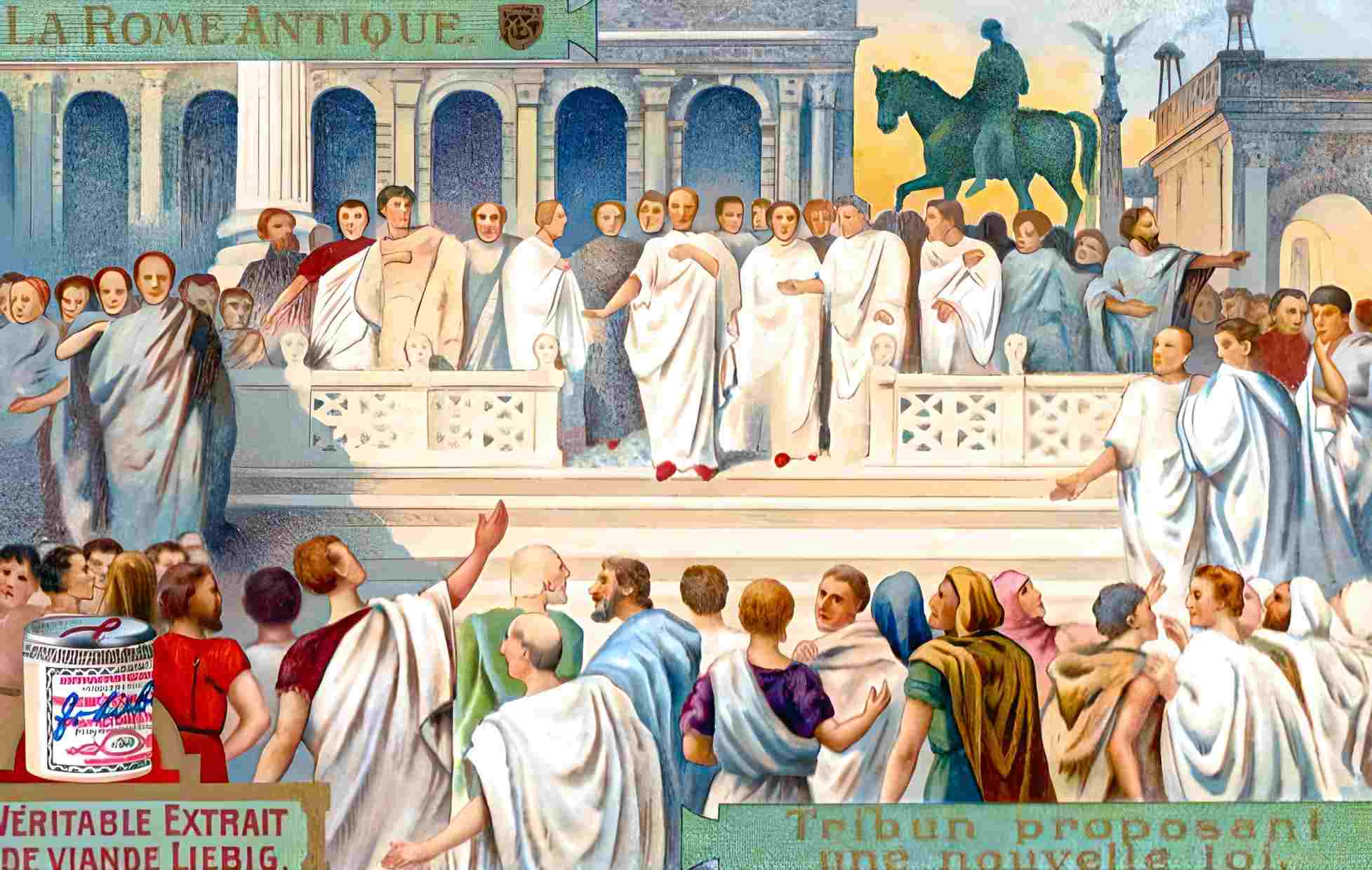

The founding of the Roman Republic

In 509 BC, at Lucius Junius Brutus’ (545–509 BC) instigation, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus was overthrown and a new rule, the Republic, was established in Rome. Considering that Athens was expelling the Pisistratids (tyrants; a personal and populist form of government) at the same period, the date was up for question.

In any event, the loss of Etruscan dominance in the area was obvious by the end of the 6th century and the beginning of the 5th century. Following its liberation from Etruscan rule, Rome saw a slowdown in the rate at which Hellenic artistic influences were being absorbed into the city’s culture. The new Roman government was based primarily on a two-headed executive authority, which the Romans took to mean a profound distaste for the absolute power of a single individual. Once a year, two praetors controlled the city, but they were soon replaced by consuls. One of the judges was given the typical royal duty of a religious leader. This job had its roots in the origins we discussed before.

The Patricians, who were based on the comitia, curiata, and centuries, continued to govern the city as before in the aristocratic assembly of the Senate. Tarquin refused to accept defeat, and he and his allies—including the people of Veii and the Etruscan king Lars Porsena—returned in force, but they were ultimately destroyed at Aricia. Since the Latin League seized weapons in 501 BC and used them to fight Rome, the Romans had been forced to rely on a dictator backed by a master of the militia for the first time in their history, ensuring that their absolute authority was limited. Legend has it that the Dioscuri (children of Jupiter) were instrumental in securing victory at Lake Regalia.

Ancient Rome: A divided society

When the struggle between Patricians and Plebeians erupted, it was a conflict of a quite different kind. The latter, which “cheated” during the regime shift that occurred almost entirely to the benefit of the former, considered the possibility of secession, demonstrating the extent to which their views conflicted. Distributing the populace into new territorial tribes in place of the old ethnic tribes, however, gave birth to a plebeian assembly that wasn’t acknowledged by the aristocracy but ultimately imposed itself nonetheless.

Simultaneously, the Comitia Centuriata (the Centuriate Assembly) structure allowed for the development, alongside the aristocratic cavalry, of a heavy infantry connected to the Greek hoplitic reform a few centuries later. The renowned Law of Twelve Tables, which laicized the right and diminished the priestly power of the patrician pontiffs, was drafted in response to the crisis that erupted about 451-450 BC. This campaign carried on, and ordinary people won civil rights (trade, marriage) as a result. As early as 471 BC, the commoners were guaranteed inviolable tribunes, who served as a check on the Senate and the most powerful aristocratic judges. When patricians and plebeians (Lex Canuleia) were finally given the same rights as each other in 440 BC, the issue was resolved.

The beginnings of the Roman expansion

Rome, strengthened by its institutions, set out in 395 BC to conquer its eternal enemy, the Veii, and brought back massive loot as a result of its conquest. The Romans’ temporary reprieve from their hazardous neighbor did not last. In 390, Rome was sacked because of a Celtic invasion. The Capitol was the only building left unharmed since the defenders had dug in there. After the Celts were weakened by a plague, they consented to negotiate with the Romans. However, when they heard the Romans’ complaints, the Celtic chief, Brennus, would have thrown his sword into the scales used to weigh the indemnity, proclaiming “Woe to the vanquished” (Vae Victis).

This defeat left an indelible impression on Rome, and it wasn’t until half a century later that the city began a series of confrontations with another Italian nation, the Samnites. The formidable warrior peoples entrenched in the Apennines between 343 and 341 BC, again between 327 and 304 BC, and again between 298 and 291 BC caused the Roman civic army armed in the style of the Greek phalanxes significant difficulties, forcing the Romans to adjust militarily.

They therefore developed the so-called manipular system; a maniple was a small subdivision of the army composed over two centuries. With these smaller forces, the Samnites could be wiped out even in difficult terrain. The aristocracy and religion had been key dividing lines in Roman society up until this time, but the opportunity to compete for the sovereign priesthoods was granted to the plebeians at this time (Lex Ogulnia, 300 BC), marking a major shift in Roman civic life.

Conflict, however, resumed its rumbling. The alliance of Taranto with King Pyrrhus of Epirus caused serious problems for Rome. However, the Hellenistic sovereign’s successes were handed down through history like the extremely costly human lives in its own ranks (the Pyrrhic victory), and the Romans took advantage of this to strike back with force and take over Taranto in 272 BC.

Rome against Carthage; the fight to the death

Rome and Carthage, the other major power in the Western Mediterranean, had been in diplomatic communication since 348 BC. In 306, the superpowers agreed to extend their previous pact. Rome, the mistress of Italy and liberated from Epirotic claims, and Carthage, in full expansion toward the Italian islands, soon came into contact on the occasion of a relatively minor event: The appeal of the Mamertines to Rome because they were besieged by the Carthaginians in Messina. When the Romans became involved, it sparked a war between the two competing empires over their shared interests and, in particular, the subject of Sicily.

Also read: Punic Wars: Three wars between Rome and Carthage

The Romans quickly adapted to this new strategy throughout the fight, which took place mostly at sea. The wars occurred between 264 and 241 BC. Slowly but surely, Rome triumphed, eventually landing an army on Carthaginian territory, where it was promptly annihilated by Hamilcar Barca, the father of the future military genius Hannibal. However, after becoming weary of battling, the Punic city agreed to negotiate with Rome, which was a huge boon to its mostly commercial activities. In that area, it lost Sicily, the major base of its navy, and later Corsica and Sardinia, thanks to ambiguities in the treaty. It had to pay a hefty indemnity for the conflict, which depleted its resources and led to a mutiny among its mercenary forces. With this victory against a major opponent in the Mediterranean, Rome was able to establish itself as a global superpower.

During the Second Punic War

Hamilcar’s family, the Barcids, were fueled by a desire for vengeance after the conflict’s cruel resolution, and they used the Iberian Peninsula’s abundant manpower and material resources to carve out a vast dominion in Spain. As of this time, Rome had successfully fought out the Celts in the Po Plain and the Illyrians on the other side of the Adriatic Sea, therefore solidifying its dominance in Italy. Hannibal’s seizure of the Spanish city of Sagonte went against the ongoing treaties between the two nations and served as the catalyst that set them in motion.

Rome was suddenly faced with a conflict that the Carthaginian commander had meticulously planned for after the loss of an ally. Hannibal, with a mixed army of Iberians, Celtiberians, Lybians, Numidians, and Carthaginians, swept over the Alps without a single loss to begin a string of stunning triumphs. He demonstrated his tactical supremacy at the Ticino and the Trebia, paving the way for his army to march south and ultimately enter Rome. Along the trip, he amused himself by ambushing the consular force dispatched to meet him in a massive ambush near Lake Trasimene. Caught in the trap, the Romans and their allies were either killed or drowned.

A total of over 80,000 consular soldiers were pursuing Hannibal when he left Rome and headed east. The Carthaginians, with a force of fewer than 50,000 men, were reportedly in serious trouble after being surrounded by hostile forces and cut off from their stronghold. He seemed desperate as he neared the Battle of Cannae, where neither the Celts nor Rome’s Italian allies had shown any desire for a rebellion. Hannibal formed an arc in front of his army to attack the enemy (composed of Spaniards and Celts), sent his phalanxes scurrying in columns behind them, and finished with his Carthaginian and Numidian cavalry.

The victorious Punic cavalry was carried at the same time on the backs of the Roman army, which was annihilated. There were around 45,000 Romans dead and 10,000 captives, according to the most credible accounts. The shattered remnants of this army flooded back into Rome, bearing word of the catastrophe. There were about a hundred senators killed, including the illustrious Lucius Aemilius Paullus, and the loss of over a hundred senators, including the illustrious Lucius Aemilius Paullus, was the worst defeat ever suffered by the Roman Empire.

But Rome didn’t give up, as the rules of Hellenistic warfare said it should. Instead, it made Fabius Maximus, who was known as the cunctator (temporizer), the dictator (a judge who gathered all the powers for a period of six months). It also strengthened itself socially by making a true “Sacred Union,” and it pushed its forces toward the only possible outcome: victory or death.

Since Hannibal was trapped in Italy and harassed by the Romans, he was unable to stop the Romans from opening a new front in Spain, on the same territories as Barcidus, with Publius Cornelius Scipio, the future African, at the helm. Scipio, the newly elected consul against the laws in force (he had not completed the cursus honorum or career of honors: continuation of magistratures of more and more important, which must carry out all the members of the aristocracy wishing to exert a political role), had previously only served as edile (it remained to him to be quaestor and praetor before running for the highest magistrature). However, the Romans eventually came to accept numerous arrangements in their political system after realizing that their conventional and inflexible structure would not enable them to escape.

Armed forces made up of regular people had to be disbanded once a year so that the men could go back to farming or other civilian pursuits. The authorities, however, were unable to disperse jaded troops due to the nature of the war. As we will see in this quick overview, the violations would have far-reaching consequences. It wasn’t long until Scipio arrived in Carthaginian territory and destroyed Hannibal’s brothers, prompting Hannibal to recall and return with a smaller force of veterans.

At Zama, in 202 BC, the two sides finally met head-on, and Hannibal prepared to provide a fresh recital of his tactical abilities. Separated into three rows, his army consisted first of Celtic and Ligurian mercenaries, then of Carthaginian levies, and lastly of his elite force, 10,000 veterans from Italy. He deployed eighty elephants in front of the legion to disrupt their otherwise perfect formation.

The Roman army was hierarchical, with the youngest serving as velites (skirmishers) and the oldest as extremely heavy triarii, passing through the hastati and the principles along the way. Scipio maintained a highly intellectual demeanor in his presence.

But it possessed a decisive asset: the Numidian cavalry had crossed into its camp thanks to a dynastic feud, and Hannibal could only muster so many. When the latter attacked with elephants, the legionaries spread out and slew the pachyderms, rendering the attack futile. The Romans countered with their own onslaught, which eventually met the first Carthaginian line and forced them to retreat after a costly loss.

Then, the Romans destroyed the Carthaginian lifts, which were later mounted on the backs of the veterans. This was all part of Hannibal’s master strategy; the exhausted Romans faced up against a massive line of infantrymen, the core of which—the Carthaginian elite—was invigorated and ready to go in contrast to the battle-hardened legionnaires. The Romans’ Numidian cavalry had already won the battle on the flanks, and now they were turning the tables on Hannibal’s Punic army and bringing about its swift demise. However, Scipio the Victor had recently learned a tactical lesson that only his sense of command could turn around. He had forbidden his cavalry to pursue the Carthaginians who had broken the combat voluntarily on the orders of Hannibal in the hopes of moving them away from the battlefield, the Punic hoping to overcome before Hannibal’s return.

Supremacy of ancient Rome in the West

There was no longer any chance of a comeback for Carthage, so they capitulated to their conqueror. The Romans showed no mercy, demanding the Punic city hand over its fleet and pay a fresh war indemnity while also causing it to lose a chunk of land in Africa and Spain to the Numids of Massinissa. When Rome first adopted what is now called “conscious imperialism,” the city was primarily operating from a defensive stance and trying to break free of a grip. Despite its demographic and material devastation, Rome now had the elements at its disposal to not only rebuild itself but also to claim a much greater dominance. It was confident in its strength, proud of its accomplishments, and strengthened by its deep organization (by the agreement between plebs and patricians).

Philip V of Macedon, who had drawn a meeting with Hannibal and spoke of his worry about Roman triumphs, was the first to fall prey to these allegations. The brief conflict began the day following the tragedy at the Battle of Cannae and ran concurrently with the second Punic War, which had been going on since 215 BC. However, the Romans had other concerns and abandoned their Aetolian friends when it came to Philip.

However, in 200 BC, Rome was so powerful that it disembarked in Macedonia after a great triumph. Titus Quinctius Flamininus showed the worth of the legions by defeating the Macedonian phalanges with Cynocephalus. The military leader, known as the “imperator” (a title of command that gave authority to the troops), declared Greece free. That he lived during a period of intense interest in ancient Greek culture is attested to by the fact that Flamininus served as a vivid emblem of this trend. Rome’s strong resistance against this overwhelming penetration of “Greekness” and reaffirmation of its own distinctiveness started with Cato, a politician who became consul in 195 BC.

In the affairs of the East

Rome’s involvement in Hellenic politics brought the Romans into touch with the Seleucid Empire, the greatest section of Alexander the Great‘s empire and approximately analogous to the Achaemenid Persian Empire. Rome’s new foe seemed formidable at first, but the victories at Thermopylae against Aristonicus III and, most notably, Magnesia ultimately established Rome as the economic arbiter of the whole Mediterranean. When the Romans finally overcame the Seleucids in battle, King Seleucus I opted to make peace with them via the Treaty of Apamea, even though it meant giving up all of his territory in Asia Minor until the Taurus Mountains.

Rome used this opportunity to strengthen its regional ally, the Pergamon kingdom. Even though Macedonia had been put through a lot of hardships since Cynocephalus in 197 BC, the country’s destiny was not sealed, as Philip’s son Perseus planned to get retribution. In defiance of international agreements, it recreated its army and formed alliances with the Seleucids in Greece.

Not willing to wait, the Romans stepped in during the third Macedonian War, which broke out in 172 BC. Perseus’ army was defeated at Pydna in 168 BC, and Macedonia was re-established under the leadership of Lucius Aemilius Paullus. Rhodes was penalized for its past assistance to the Macedonians, losing land in Asia Minor. Meanwhile, it must let Delos develop tax-free, like a free port, thereby losing vital marine trade.

War in the West

The ease with which the Hellenistic kings ruled allowed Rome to win the East. However, operations on the Western side were far bloodier and looted much less. The Celtiberians engaged the Romans in a type of “guerrilla warfare” to prevent the Romans from exploiting the territory they had conquered from the Barca family in Spain. The Romans sent two bankers in 197 BC to manage the two newly conquered provinces. But the difficult task of actually subjugating the area remained.

Despite Marcellus’ campaign between 154 and 152 BC, peace had not been established by 147 BC. Viriathe, a former shepherd and survivor of the slaughter perpetrated by the forces of the Roman moneylender Servius Sulpicius Galba in 150 BC, under the context of pacification, became the heart of the resistance movement.

His family, presumably persuaded by the Romans, killed him after he had already achieved numerous victories and stubbornly resisted. Despite the triumphs of the Lusitanian commander, the Celtiberians, who had reclaimed their weapons, remained on the brink of conflict. At the end of the third Punic War, when Rome’s adversary Carthage was finally destroyed, the Romans sent their strongest commander, Scipio Aemilianus, the son of Lucius Aemilius Paullus. The fighting lasted from 137 until 133, at which point the Romans finally demolished the fortified city of Numance and trapped the defenders within.

New internal tensions in Ancient Rome

But inside its borders, Rome was rocked by a series of remarkable events. First of all, the Gracchi brothers’ reform efforts were a watershed moment in Roman history, signifying the break between the conservatives, conservative liberals, and reformers within the nobility. When the large landowners bought up or simply expropriated the farms of the little guys, the farmers were forced to submit to their exploitation. Now, however, a large number of impoverished farmers relocated to Rome in an effort to join the city’s struggling populace.

Aristocrats had monopolized huge areas on the ager publicus (public domain; lands belonging to all Roman citizens) through entrustments that were not final gifts, enabling the state to retain the property. The aristocracy was outraged by the Gracchi because they intended to force a transfer of the estates, which ultimately led to their deaths.

Simultaneously, between 135 and 132 BC, the slaves of Sicily rebelled, prompting a severe suppression by the Roman authorities and setting off a chain reaction of similar revolts, during which the Romans learned to be careful of such an inflow of slaves. The revolt led by Spartacus, who was ultimately defeated by Crassus and Pompey in 71 BC and resulted in the crucifixion of six thousand captives along the Appian Way, was the most well-known.

Arrival of the Barbarians

In order to secure a reliable route to their holdings in Spain, the Romans established the province of Narbonnaise in the external region by gradually subduing Transalpine Gaul (beyond the Alps) in the years about 120 BC. However, Rome was soon confronted with fresh and especially dangerous threats; in fact, Cimbri and Teutones tribes came down from the north of Germania and began a migration that brought them across Europe and ended in Noric, in the north of Italy, in 113 BC. In response to this danger, the Romans intervened, only to suffer a crushing defeat at the hands of their opponents in the Battle of Noreia.

Going onward, the Germanic barbarians crossed into Gaul, did a big loop around the Celtic territory, and eventually settled in the brand-new province of Narbonnaise. The Romans eventually tracked down their foes in a massive battle close to Orange, where they were soundly defeated and slaughtered once more. The barbarians left Italy and traveled across northern Spain and back to the Italian peninsula in search of land. In Rome, however, a member of the equestrian order was promoted to the rank of general and given control of the military operations; this man would go on to defeat the barbarian threat in two decisive battles, first at Aquae Sextiae and then at Verceil (102 and 101 BC).

However, Rome was permanently scarred by its fear of the barbarians of the North, who were depicted in iconography and bas-relief as beastly, hirsute, and battling beings. This fear was so pervasive that a large portion of the historiography (history of history) of the 19th century was characterized by a rejection of these peoples, with historians literally taking up the words of their Roman forebears. Germans, a diverse people whose uniqueness continued to shock and fascinate the Romans, had to have a special relationship with the ancient city.

Nonetheless, a Numidian prince saw an opportunity to enlist Rome as an ally in his bid for the throne. Simultaneously, the Romans used military force to end a conflict known as the Jugurtha War, so named after the Berber king (from Numidia) who conquered and expelled his rival. The fights were tough; the Numidians had served on the side of the Romans as allies during the war in Spain and therefore knew Roman tactics. Rome did not achieve victory again in Numidia until Marius (106 BC) was appointed, and it was only after he had proven himself as a commander that a protectorate rather than full annexation was extended.

Marian reforms

But Marius wasn’t just a war hero; he also led a massive overhaul of the Roman army by enlisting “proletarians” in the fighting (until then, only citizens with sufficient means could serve since they had to equip themselves at their own expense). Since the soldiers had little to look forward to in Roman society, they grew closer to their leader and lost interest in returning home as soon as possible. The prospect of financial gain was another incentive for them to engage in these wars of conquest.

In 107 BC, Marius chose to modernize the army by giving each soldier a bigger load, which helped reduce the train of luggage that weighed down and slowed down the forces and earned them the derisive appellation of “mules of Marius.” The general’s deed was linked with a political claim, and he was the first of the Great Imperatores to exert actual control over the Republic.

The legacy of Attalus

It was prudent, however, to discuss the other military and political facts on the Eastern side, where Rome was gradually interfering, before delving into the inner struggles of the Roman military aristocracy, as we did earlier. With the help of a will written by Attalus III, Rome annexed the former kingdom of Pergamon in 113 BC, but the transition was not smooth, as Attalus III’s half-brother, Aristonicus, sparked resistance by declaring himself king. When Rome became concerned about the plundering activities of pirates based in Asia Minor, it decided to conquer the region and establish the province of Cilicia there (100 BC).

This concludes the first section, as the years that followed, up until 31 BC, were marked by a string of armed and political conflicts that would benefit from individual study in order to convey their substance. After all, we’ve witnessed the Roman Empire’s expansion over several centuries, which brought the tiny Italian city under the very first diplomatic plan for the Mediterranean.

Italy, much of Spain, the southern part of Gaul, a narrow coastal strip in Illyria (the Balkans), Greece, Macedonia, the western part of Asia Minor, and the old African territory of Carthage were all under Roman control at this time. Despite this, the Italian city assumed its imperialism and power, exerted it across the entire basin and mediated succession disputes in neighboring kingdoms like Numidia. The mission to subjugate the civilized world, which it believed was the only group that should be required to abide by its laws, had become personal to it.

Rome’s political stability over the centuries had allowed the city-state to emerge from perilous situations by drawing its social fabric closer together, despite the presence of strong tensions. As if that weren’t enough, Gaius Sallustius Crispus (Sallust) sings the city’s praises in a text of his own, explaining how, after Rome had been supported by exceptional men, the city’s buildings were the only things that kept him from imposing himself on the rest of the world. This foresight reflected the Romans’ optimism about their republican government, which would eventually collapse under the strain of civil strife.

A city in full glory

After Rome’s victory against the Germanic tribes and the ruler of Numidia, we are now leaving the city while it is still on a high note. These hard-won victories would not have been achievable without the assistance of a major figure in Roman history, Marius. We are getting close to his military reforms; it is time to start looking at his politics. Most importantly, after the Gracchus era, Rome’s power struggle polarized into the two main camps that had been at odds ever since.

The two brothers were members of the populares, a group that advocated for the people’s interests by occupying positions of power, most notably the tribune of the plebs. Due to the holders’ inviolability and the veto power they had over Senate decisions, these magistratures carried a disproportionate amount of weight in Rome. During Rome’s power struggle, the populares stood in opposition to the optimates, who fought for Rome’s greater good while still protecting their own privileges.

The arrival of the victorious general here shifted the equilibrium of power. Marius reclaimed some of Gracchus’ policies by aligning himself with tribunes of the plebeians and leaning on the populares (he was of equestrian origin, i.e. a rank of the aristocracy lower than that of the senatorial order). This focused especially on the agricultural reforms and the handling of the destiny of Italy’s allies, who wanted Roman citizenship as a matter of right but were embarrassed by the incomplete changes launched by the Gracchus.

Although Caius and Tiberius Gracchus intended to reclaim ager publicus territory in order to settle the poor there, they unintentionally ran smack into occupied ager publicus property that was crucial to their alliance’s survival and their own economic exploitation as a result of their measure’s extension.

The Gracchus had proposed making these Italians Roman citizens as a means of solving the problem, but the aristocracy had violently rejected this idea. When they were killed, there was no way to know for sure what had happened. Additionally, the Italians had complicated the matters by moving the capital to Rome, which reduced the potential military contingent provided by this ally of Rome.

The magistrates’ response of expulsions, while symbolic, did nothing to solve the problem. There was still a great deal of tension, and the Roman opposition to any kind of reform was strong. In contrast, Marius and his partisans would launch an attack on the defeated magistrates from the previous battle, further heightening tensions. Marius eventually distanced himself from his tribune allies and became closer to the aristocrats, who then had the troublemakers killed.

The Social War in Ancient Rome

When the lack of changes continued, the allies became frustrated and rebelled as early as 91 BC, beginning what is now known as the “social war” (from socii, meaning “allies in Latin). The war was tough, and peace was only restored by granting citizenship to all Italian allies, which rankled Rome’s political and social elites.

In fact, up until that point, a population of about 400,000 people had been subjected to the clientelistic webs of influential aristocrats in order for them to exert power over them and secure their votes. Thereafter, however, the population swelled into the millions. Furthermore, the hassle of registering these new citizens with the tribes now began.

We saw that the populace was divided into 35 distinct ethnic groups. As a result of the distribution of these new citizens, the Romans’ voting power was reduced. It was then suggested that new tribes be formed or that the recent citizens be registered in only 8 or 10 of the already existing tribes through reservations, which would have mitigated the potential for widespread disruption by limiting the number of people entering the building at once.

This impasse was broken when a populares tribune of the plebeians, a supporter of Marius, decided to register the new citizens in the 35 tribes, despite the tribes’ vehement opposition. Using this opportunity, he announced a new campaign in the East and named Marius general of the force.

The war against Mithridates and the fight between Marius and Sulla

Mithridates VI Eupator, a Hellenistic king, ruled with great authority on the shore of the Black Sea, known at the time as Euxin Bridge. There were other Asia Minor monarchs vying for power in the region, and they sought Roman assistance in vanquishing his threat. Nevertheless, Mithridates prevailed, and his armies occupied the Roman Empire’s Roman-allied kingdoms and the Asian province.

The Romans, who had been exploiting the province with great ferocity up until that point, were the targets of a widespread uprising that he inspired. The Roman government did contract with private firms known as “publican companies” to collect taxes on its behalf. They forwarded the State a portion of the estimated tax revenue, and then traveled to the provinces to recoup their losses.

The bigger the profit, the better it was for them. As a result, the populace was under extreme stress; news of Mithradates’ arrival must have been welcomed. At the same time that the horrific massacres of Romans and Italians (estimates range from 80,000 to 150,000) were taking place, Greece and Macedonia sided with the king. Marius was to be dispatched during this time of crisis because it offered his camp the chance to gain notoriety and, by extension, power, even without considering the loot that might be recovered.

In Rome, however, the consul Sulla was the one who, according to all reason and the letter of the law, was tasked with leading the campaign. This was the first known instance of a general being removed from command without cause. When Sulla arrived in Rome, he found that his army had already been assembled, and the proscriptions had given the massacres a legal basis for the first time. Marius and his allies were able to escape the purges. After Sulla, who came from an ancient aristocratic family himself and was thus patrician, refocused policy in favor of the optimates, he embarked on a military campaign in the East and achieved the earliest Roman victories in Greece.

At the same time, however, Marius, overcome with vengeance, returned to Rome and set up a government that served the people rather than the elite. They dispatched an army to Asia Minor to engage Mithradates head-on, earning the distinction at Sulla’s expense. Aware of his dwindling options, the king eventually decided to treat Sulla, who demanded that he surrender all of his conquests in exchange for a relatively paltry tribute of 2,000 talents. This demonstrated that Sulla had specifically in mind the idea of liquidating this war in order to turn his weapons against his political enemies.

It was at this point that the operations began, but Sulla had already gathered the core elements of his enemy’s army around him. In the time since Marius’ death (86 BC), the Marianist camp had found itself defending Sulla’s return to power once again. Sertorius, an ardent supporter of Marius, took up arms and federated the Spanish people to fight against the party of Sulla, but the resistance was strong in the provinces, especially in Spain.

The Sullanian restoration

After achieving victory, Sulla restructured the Roman State in a way that he believed to be fair but that avoided some difficult issues. The tribunes of the plebs, an organ that had previously served popular ambitions, had their power significantly curtailed as part of his restoration, which was perhaps the most important measure of his success.

His model failed to address the needs of the wealthiest aristocrats, and as soon as he resigned—in accordance with his desire to restore the Republic’s financial footing—agitation resumed, first and foremost among the Italian citizens who had been coerced into accepting the installation of some 80,000 veterans of the Sulla armies in their communities.

Second, the rising price of wheat in Rome was directly attributable to the piracy that plagued the Mediterranean. Last but not least, Spartacus’s revolt was the pinnacle of the slave uprisings. The issue of restoring the tribunes of the plebs’ power in its entirety kept coming back up on the political agenda inside. There were cracks all over the shaky Sullanian structure.

Pompey against pirates

Rome obviously took the external problems seriously if discontent had a genuine background in Italy. A young lieutenant of Sulla named Pompey managed to convince the tribune of the plebs to give him consular military command over the entire Mediterranean and up to 70 kilometers inland, along with ships and funds, so that he could put an end to the pirates’ reign of terror. At the end of 67 BC, or within a matter of months, he was liquidated.

Even though Mithridates had resumed his actions against the Roman allies, Pompey launched an offensive against him, defeated him, and pushed his offensive until Armenia, taking Roman weapons further than anyone had before. He also conquered Syrian territory and advanced to the border with Egypt. After amassing so much fame on the battlefield, he spent ten days in prayer to the gods, praising them for the blessings they had bestowed upon the Roman people. It was now official that Rome ruled the entire Mediterranean and all of Asia Minor, including Syria and Palestine.

The first triumvirate and the Gallic Wars

In Italy, after several defeats, the Romans, thanks to Crassus, the richest man in Rome, got rid of the cumbersome, revolting slaves. On the other hand, Pompey was present to claim his due honors by slaughtering some of the deserters from the army that Crassus had just defeated. When his rival won, he had to settle for the standing ovation he received, despite the fact that he had only achieved a minor victory. This caused him to grow very resentful.

That’s when the appearance of a certain famous persona began: Julius Caesar. Determined to secure his own financial future, the young man had spared no expense during his adolescence in providing lavish entertainment for the public. He was awarded the sovereign pontificate and a command in Spain not long after, allowing him to start amassing his well-deserved fame and fortune.

When he got back, he made peace with Pompey and Crassus, the two other major players in Rome at the time. The agreement was known as the first triumvirate because it was a genuine three-way partnership that helped bypass the political locks of Rome that had been set to moderate the regime and prevent the return of the monarchy. Pompey’s fame, Crassus’s wealth, and Caesar’s ambition all came together in this deal. By reaching this pact, he was given pro-consular command over the northern regions of Italy and the Balkans, and later over the southern regions of Gaul. From there, it took advantage of the unrest brought on by the Germans’ invasion of the Celts and went on the offensive in 58 BC, defeating the formidable but ultimately doomed Ariovistus.

As his campaign progressed, he was able to subjugate all of Gaul with the help of the son of his friend and colleague Crassus, who advanced in Aquitaine while Caesar was busy in Belgium. In order to leave his mark on Rome and capitalize on his victories, he led a campaign in (Great) Britain and collected tributes before crossing the English Channel and directing his troops across the Rhine using a makeshift boat bridge. He won the respect of many Romans, including Cicero in particular, for surpassing Pompey’s achievements and for leading the Roman army and its imperial eagles into previously uncharted territory. But the prestige that Caesar accumulated far away made grow, in Rome, the enmities.

In the unrestrained competition for power, the aristocrats’ ability to claim entry into the game became increasingly rare, to the point that the financial and military requirements became astronomical; Pompey, Caesar, and Crassus were each much more powerful than the other great names of Rome, even Cicero or still Cato of Utica, which could prevail only through its strict observance of the rules of old Rome. Caesar convinced the other two triumvirs to grant him more authority in Gaul, allowing him to consolidate his conquest after the dangerous revolt of 52 BC, led by the young Arverne Vercingetorix, was crushed.

He gained not only fame but also an enormous fortune and an army of seasoned fighters who all rallied for his cause. Along with them, Julius Caesar entered a new phase of aristocratic competition, a competition that turned into a duel after Crassus, feeling diminished by his colleagues’ success, launched a massive expedition against the Parthian Empire in 53 BC (current Iran). In one of the worst Roman defeats ever, at Carrhae, the triumvir led seven legions to capitulation and execution at the hands of the Iranian horsemen.

Caesar against the Senate and Pompey

Finally labeled an enemy of the state, Caesar was called back to Rome to face trial by the Senate for his role in initiating and leading an unauthorized military campaign in Gaul. Because of how difficult his path to the throne had been, the emperor had no intention of giving up his reign so quickly. Following Rome’s lead in 50 BC, he led his army in that direction. His famous phrase, “Alea jacta est“, literally “The die was cast“, would have been uttered when he reached the boundary of his command zone, symbolized by the Rubicon, a small river.

After all, he was well aware that if he abandoned the realm in which he exercised his legal power, he would be forced into a military conflict with the Senate and Pompey, with whom he had lost all personal ties following the death of Caesar’s daughter, who had been married off to Pompey to secure their alliance.

Since Caesar had already taken Rome by storm, the Senate fled with Pompey to the East, where the latter knew he could quickly assemble an army of aristocrats, veterans, and kings to fight back against the dictator. Caesar, however, had just gained a significant advantage by physically seizing the center of the Roman Empire, the residence of the “people’s king,” and the seat of Roman law. He began to plan the next steps, including his confrontation with Pompey, and he filled the Senate with men who were dedicated to his cause.

The Triumph of Caesar

The year 48 BC was a watershed moment in the final showdown, as the Senate, allied by circumstance with Pompey, had gained the East and was preparing for war against a Caesar who had taken a clear ascendancy over his enemies through audacious initiative. By following the momentum of its movement, it arrived at the Pompeian party’s gathering. Despite Pompey’s superior numbers and fortifications, Caesar was able to crush the locals of Dyrrachium.

He had to flee from his rival, who was hot on his trail after his troops foolishly engaged in the area and were subsequently slashed to pieces. On the plain of Pharsalus a month later, however, Caesar, ever aware of the numerical superiority of his enemies, made all his talent speak, allied with the roughness of his Gaulish veterans.

Caesar, aware of his weak cavalry, deployed eight cohorts in ambush, which, during the battle, filled the void left by the retreat of his cavalry and pushed back even that of Pompey before reversing the enemy army, which had almost encircled it, and breaking the combat. Following a devastating loss, Pompey fled to Egypt, where he was eventually assassinated. However, Caesar was far from completing the war that would make him the undivided ruler of the Roman Empire. He then followed Pompey to Egypt, where he captured Alexandria and declared himself the protector of the kingdom.

And so began his fairytale romance with the legendary Cleopatra. However, the citizens of Alexandria quickly rose up in rebellion against the outsider. Caesar, trapped within the city, regained control. He then learned some disturbing news from Asia Minor: Pharnaces, king of Pontus (a Hellenistic kingdom whose center of gravity was the present-day Crimea), heir to the legendary Mithridates, had just invaded Roman territory and defeated the Roman governor.

With no time to waste, Caesar went on the offensive, swiftly crossing Syria and Palestine to arrive in the east of Anatolia to face his opponent. Caesar’s army once again showed its effectiveness in the 47 BC battle at Zela. Caesar’s famous motto “Veni, vidi, vici” (literally “I came, I saw, I conquered”) was put to use, and the enemy was quickly crushed and driven back. Upon his return to Rome, he was named dictator for a year.

He went on the offensive once more in 46 BC, this time in Africa against Pompeian elements who were getting ready for battle. Thapsus was the site of the gathering. Caesar’s troops were put to the test to the breaking point by the elephants, but he was able to rally the troops and push them back. He then capitalized on his initiative to seize the enemy camp and push the enemy’s troops, showing no mercy to them at all.

In the wake of this defeat, his sworn enemy, Cato of Utica, committed suicide. The dictator wasted his time back in Rome because Gnaeus, the son of Pompey, was besieging the city of Ulpia in Spain, which had remained loyal to Caesar despite his departure. That being the case, he hastily set sail for Spain, where he ordered the siege to be lifted and the opposing army there crushed at the Battle of Munda (March 45 BC). When he was welcomed back to Rome and given dictatorship for ten years, the republican powers completely failed to exercise moderation.

For his many victories, Caesar was showered with accolades and eventually made dictator for life. He was at the pinnacle of his power and influence at the time. All of the military threats against him had been eliminated. Since he was now a dictator for life, all obstacles to his continued rule were also eliminated. He then started making preparations for a massive campaign against the Parthian kingdom, Crassus’ tomb, and his army.

The conspiracy and the Ides of March

But the aristocracy, seeing itself reduced to a thin competition for subordinate honors, began to develop sharp enmities in response to the empire’s glory and power. Furthermore, since the fall of kingship in Rome, the idea of one man holding absolute power had been met with great suspicion. The republican system was shaped by this genuine fear, which was why its highest magistracy, the consulate, was composed of multiple judges. Very clear suspicions began to be born on a possible Caesarion would put on the diadem and proclaim himself king.

Almost immediately, a plot was hatched, and where Pompey and his successors’ weapons had failed, this one was ultimately successful. Caesar was murdered by the conspirators, who included his adopted son Brutus, on the Ides of March, 44 BC, in the Senate. The conspirators’ end goal was to remove the tyrant from power so that the game of competition between the ruling class could resume. It involved covering up the systemic problems that had been building up since Marius and denying the trends that had been indicating that the system was in trouble.

The failure of the republican restoration

The Roman world was in a state of shock after losing both the man who threatened the regime’s very existence and the man who had won so many victories for Rome’s honor and restored peace throughout the Empire. In an effort to restore ancient Libertas, the conspirators planned to have his body dumped in the Tiber and all of his decrees nullified. The public’s opposition, however, stopped them from completing the project. This was because Caesar’s policies aligned with the principles populares that it defended.

Despite the dictator’s death, other figures were now poised to inherit his power and wealth. His first and most loyal lieutenant, Mark Antony (Marcus Antonius), was left as consul after Caesar’s death. Marcus Aemilius Lepidus, his master of the cavalry, held the second-highest rank and was traditionally stationed next to the dictator in order to limit the dictator’s absolute power. Octavian (Augustus), the small nephew of Caesar but especially his adopted son, was the third, but he remained effaced because of his youth (19 years old) and inexperience in military affairs. Each one undertook in the months that followed, a little timidly, to draw their pin from the game in the immense vacuum left by the disappearance of Caesar.

Mark Antony compelled himself to donate Caesar’s will and fortune, showering the populace with gifts to win their favor. As for the conspirators themselves, they were cut off from Rome and eventually abandoned their delusions of grandeur. As Octavian was in Apollonia, he received the news of his relative’s passing. Then he decided to pay a visit to his seasoned soldiers, who now looked to him as their leader. He made an impressive debut in the competition by enlisting the help of three thousand of them.

Second triumvirate

The Senate did not disarm, and the conspirators withdrew under Cicero’s leadership, but this marked the beginning of the war against Mark Antony and the beginning of a long series of civil wars. Since he lost, Antony had no choice but to flee to Provence. The assembly had sided with Octavian, but now this one had been named propraetor (a position that necessitates having completed the office of praetor in the cursus honorum and thus being at least 30 years old, giving the command on a province with a military command, the imperium reduced compared to that of the consul and the proconsul) and, possessing thus the imperium, marches at the head of eight legions on Rome.

After that, he plundered the State’s coffers and gave the loot to his troops. Instantaneously, he appointed himself consul. As a result of the senators’ outrage, Marcus Aemilius Lepidus was tasked with mediating peace between Octavian and Antoine, which took some time but ultimately succeeded. After that, the three of them established the second triumvirate, which, unlike the first, was a formal agreement codified in law.

The results were almost instant. A proscription was instituted, and it was estimated that 300 people lost their lives as a direct result of Cicero’s death (150 senators and 150 knights). Lepidus was given control of Narbonese Gaul and the Iberian provinces, while Antony was given control of the rest of Gaul and Cisalpine (Northern Italy), and Octavian was given control of Africa, Sicily, and Sardinia, each with 20 legions.

It remained for them now to avenge Caesar from whom they all claimed the heritage. Octavian and Antony traveled together to the East. At Philippi in 42 BC, they encountered the forces of the conspirators Cassius and Brutus.

The battle unfolded over the course of two days. On the first day, Antony, who had avoided the enemy device by going south, was caught in an unresolved frontal clash with the units of Cassius, while Brutus’ troops plundered Octavian’s camp to the west. Cassius committed suicide after witnessing the failure of his troops and failing to witness Brutus’ triumph.

The next day, the triumvirs maintained their initiative, with Octavian joining Antony on his positions and Brutus meeting Cassius’ units to face off against Antony. A clash broke out, and the Caesarion forces eventually emerged victorious. The soldiers deserted Brutus, and he, in turn, took his own life.

A new division of the Roman world resulted from the triumvirs’ control of the East; Lepidus was reduced to managing only Africa, while Antony was given all of Gaul and Octavian Spain, to which it added its own possessions. Antony was given the task of conquering the rich and powerful Parthian space, following in the footsteps of Alexander the Great. This paired distribution of labor pleased everyone involved. Octavian was given the difficult task of allocating land to the veterans of the campaign in Philippi and determining the fate of Sextus Pompey, son of the great general who occupied Sicily. Leaving politics was a clear choice for Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.

Octavian and Antony: Between tension and reconciliation

There was little that was needed to spark hostilities between Octavian and Antony, but the gift of grounds proved to be a real headache for the former. The interview with Brindes gave Octavian the confidence he needed to launch a powerful attack on Sicily, which cemented his position as the undisputed ruler of the Western Empire. Meanwhile, in the East, Antony was emerging as a dominant figure. He stayed in Alexandria, and he, like Caesar before him, fell under Cleopatra’s spell, marking the beginning of a magnificent legend that has been portrayed on screen many times and has inspired a lot of writing.

Antony, however, did not lose sight of his ultimate goal. Therefore, he led an army against the Parthians, but despite not losing a single battle, he achieved no victories. It was only in Rome that the completion of this sacred ritual could be witnessed, so when he returned to Alexandria to celebrate his victory, the Romans were scandalized. Then, Octavian masterfully kept the rumors about Antony’s deviant behavior going strong in Rome.

Indeed, the Romans viewed the world and its people through a lens colored by a wide variety of stereotypes and prejudices; for example, the Gauls were portrayed as fierce warriors who lacked the capacity for thoughtful deliberation, while the Greeks were portrayed as cold-blooded schemers and calculating con artists. On the whole, the Romans saw the Orientals as soft and lascivious, the polar opposite of the cardinal virtues of sobriety, temperance, and control of one’s passions. To undermine his rival, who had been widely supported up until that point, Octavian played on the xenophobia of his countrymen.

The rupture and the beginnings of the Empire

However, in 32 BC, he ran into trouble in Rome. Without the ability to assert his authority, he was forced to leave Rome cautiously as his enemies began to stir up trouble. And then he made them make it. Following his return to Rome with his army, he coerced the Senate into declaring war on Antony and Cleopatra.

Meanwhile, Antony was getting him ready for the confrontation. He followed a strategy similar to his rival’s, pumping his armies full of intense propaganda while also increasing their numbers. The Roman world was teetering on the brink of a new violent outbreak due to the mounting tension between two opposing poles. In 31 BC, Octavian was named consul and, after swearing all of the Western provinces to his leadership, launched an offensive that took him across the Adriatic.

Fighting broke out at Actium (Battle of Actium), where Octavian’s loyal general Agrippa soundly defeated the Eastern fleet. Both defeated, the star-crossed lovers returned to Egypt, where they took their own lives and provided posterity with a dramatic apotheosis that has since been widely exploited. As in 44 BC, Rome had a single ruler, but this time the political and military opposition was completely eliminated (through proscriptions). But Octavian still had a mammoth task to accomplish, one that his adoptive father had failed to do: restoring the Republic’s stability and power without enraging the populace. This is the history of the Roman Empire.

Bibliography:

- Develin, Robert (1985). The practice of politics at Rome, 366–167 BC. Brussels: Latomus.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08125-7.

- Brunt, Peter A (1988). The fall of the Roman republic and related essays. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814849-6. OCLC 16466585.

- Taylor, Lily Ross; Linderski, Jerzy (2013). The voting districts of the Roman Republic: the thirty-five urban and rural tribes. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11869-4. OCLC 1241204151.

- Eck, Werner (2003). The Age of Augustus. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22957-5.