The Old Testament teaches that Yahweh gave Moses the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai and that those commandments were kept in the Ark of the Covenant. Stolen from the Holy of Holies in the Jerusalem Temple, which vanished in 586 BC, the covenant’s whereabouts remain unknown. There has been considerable conjecture about its whereabouts since the Middle Ages. Thus, the city of Aksum in Ethiopia celebrates Timkat by parading a draped chest representing the Ark of the Covenant. Tabot plates, representing the Tablets of the Law and, by extension, the Ark, may be seen in churches around the nation. The true Ark, locals believe, is kept at the church of St. Mary of Zion, where only one priest is permitted at a time to watch over the covenant.

Ark of the Covenant, King Solomon, and the Queen of Sheba

Tradition holds that Moses placed the Tablets of the Law (or Tablets of Stone) that God gave him on Mount Sinai into the Ark of the Covenant. It was delivered to Jerusalem by King David after a long trip, during which it served as a sign of God’s presence among his people, including during their exodus from Egypt. No source, including the Bible, makes reference to it after it was placed in the Holy of Holies of the Jerusalem Temple. Was it relocated for safety after being damaged by war or an earthquake? To date, nobody has any idea.

How plausible is the legend that Ethiopia is protecting the holiest object in all of Judaism and the three monotheistic religions? The indigenous population bases its claims on the Kebra Nagast, a document from the 13th century that states Ethiopia was formerly the kingdom of Saba and that the queen fell pregnant while visiting King Solomon. Menelik, “son of the wise man,” was born after she relocated back to Ethiopia. He went back to his family’s home and carried the Ark of the Covenant with him.

Despite the widespread disbelief in this legend, there is in fact a group of “black Jews” in Ethiopia who have been forbidden from entering Israel since the time of King Josiah. That means there must have been a massive exodus from the land of the Hebrews long ago.

The theory proposed by Graham Hancock

Graham Hancock’s research presents a fascinating theory. The migration of the Ark really occurred, despite the Kebra Nagast being a simplistic popular myth filling in a lost past. Around the year 650, during the reign of Manasseh, the pagan ruler of Jerusalem, some Levite priests allegedly sought to save the Ark by relocating it to a foreign nation. They would have arrived at Elephantine, the site of the last remaining Jewish temple, which may have been constructed by these priests specifically to house the Ark of the Covenant.

According to excavations, this temple was destroyed in the 5th century BC, ostensibly by Egyptians (in reality, by Persians, but instigated by Khnum’s priests). It’s possible that the priests left Egypt through the Nile, traveled to the Takaze, and eventually lived on the island of Tana Kirkos, where the Ark remained undisturbed for 800 years until it was brought to Aksum following the region’s conversion to Christianity under King Ezana in around the year 300.

The last traces of this epic may be found among the black Jewish community, who practice rituals (including sacrifices) that predate King Josiah’s reforms. This new race would be descended from the people who carried the Ark of the Covenant.

Protectors of a secret, the Templars

For Hancock, the existence of crosses pattées in Ethiopian churches is proof that the Templars recovered the Ark in Ethiopia and preserved it there after returning with King Lalibela. Christian churches in Ethiopia were reportedly constructed by white men, according to Portuguese explorers. Lalibela’s church is dedicated to the Virgin Mary, who has significant ties to the Ark. The king was resting against a pillar that still stands in the church, and it is said that Lalibela was inspired to build the church after seeing a vision of Jesus. The following is inscribed on this pillar:

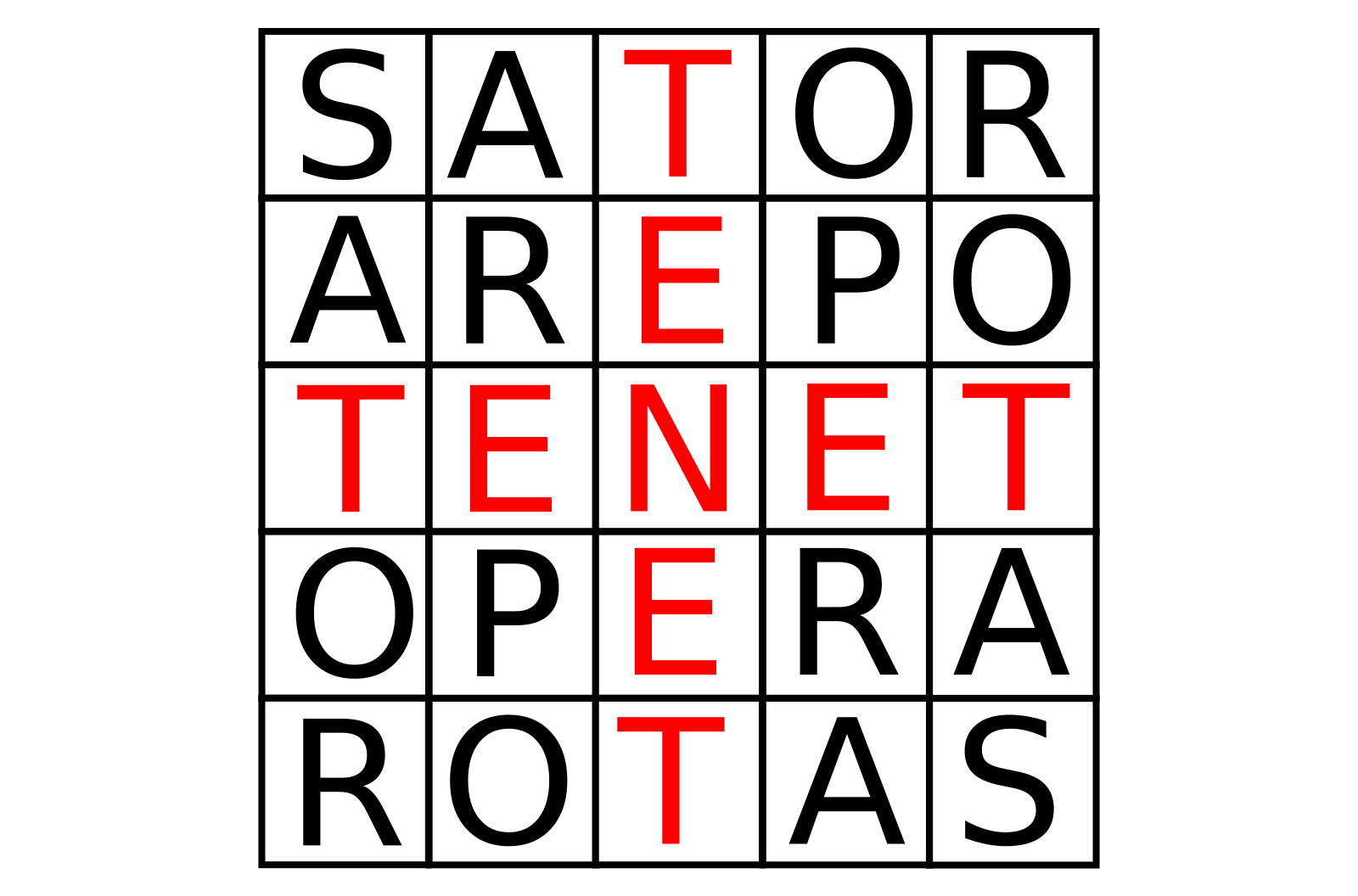

SATOR

AREPO

TENET

OPERA

ROTAS

This is called the Templar Magic Square or Sator Square, which looks like this:

On the opposite of what Hancock claims, magic squares have pre-Christian roots; in fact, one was discovered in Pompeii. In his 1207 book Churches and Monasteries of Egypt, Armenian geographer Abu Salih describes his visit to Aksum, where he witnesses two white men—one blond and the other red-haired—procession with the Ark of the Covenant.

Hancock identifies them as Templars:

“The Abyssinians also possess the Ark of the Covenant, in which are two stone tablets engraved by the finger of God with the Ten Commandments that he left to the sons of Israel. The Ark of the Covenant is on the altar, but it is not as high as this one, it only reaches the height of a man’s knee, and it is covered with gold. On the lid, there are several gold crosses and five precious stones, one at each corner and one in the center. The liturgy of the Ark is celebrated four times a year, in the palace of the king [Lalibella], and when it is taken out of the church and taken to the palace chapel, it is covered with a canopy and carried by a large number of Israelites, descendants of the family of the prophet David, who have white skin and red hair.”

Every church continues to display a tabot, a plaque depicting the Ark, as a reminder of the event. There is a legend that the Ark is kept in a secret chapel at St. Mary of Zion, and that only the “guardian of the Ark,” a priest who is appointed to the role for life, is allowed to view it.

A chest believed to be the Ark of the Covenant is paraded through the streets of Aksum during the Timkat celebration, but the Ark’s guardian stays behind in his chapel, demonstrating that the Ark does not depart even for the Timkat celebration if it is in Aksum.

From the Ark to the Holy Grail

It appears that France would have been exposed to this Templar tradition. A statue of the Queen of Sheba (Saba) with a black person at her feet may be seen on the porch of Chartres Cathedral. This appears to attest to the fact that the Ethiopian legend recognizes an African (Ethiopian) Queen of Sheba rather than one from the Arabian Peninsula. A carving of the Ark with the Latin inscription “Amittitur arca federis” or “Here is lost the Ark of the Covenant” is shown on a church pillar. While this may indicate to some that the Ark has been returned to Chartres, according to Hancock, it is still “lost” in Ethiopia.

Even the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival, which was published about 1170 or 1220, follows this Ark tradition by naming the Templars as the Grail’s keepers. In his work, the Grail is a stone. He describes how the knights’ search for the Holy Grail took them beyond the city of Rohas, the former name of Lalibela. In that, a man named Parzival learns about his African half-brother named Feirefiz.

In contrast to other interpretations, the Grail in this one is a stone. Melchizedek, the priest-king of Israel, is shown on the cathedral’s portico in Chartres holding a cup with a sphere within it, which has been variously interpreted as the Grail containing a stone.

But because the bread is used to celebrate Abraham’s safe return from the campaign, the chalice and the bread appear like the most plausible candidates.

King Melchizedek of Salem, a priest of the Most High God, provided the bread and wine to bless Abraham. In his blessing, he said:

“Blessed be Abram by God Most High,

The 14th chapter of Genesis.

Creator of heaven and earth.

20 And praise be to God Most High,

Who delivered your enemies into your hand.”

His depictions often include a loaf of bread and a chalice. There are many who believe the Ark of the Covenant was brought from Ethiopia to Israel as part of Operation Magic Carpet, which saw the return of African Jews to their homeland.

Is the Ark of the Covenant in Ethiopia?

Ultimately, Hancock’s study is simply a set of “possibilities,” and there is no hard evidence to suggest that the Ark of the Covenant is located in Ethiopia. The fabled relic is critically important to Ethiopian religion and, by extension, to the country’s sense of itself as a people. The danger of being accused of lying is too great for any leader to risk studying it. Perhaps the yearning to bring people together could have inspired the construction of a fake artifact.

While the story of the son of Sheba is undoubtedly a fable and the migration of the Black Jews is not evidence of the recovery of the Ark to Ethiopia, the enigma supports the Ethiopian national cause. Last but not least, if the Templars visited Ethiopia, the relic may not be genuine because of the cult they brought with them.