Atum or Tum Neb-er-djer, the Lord of the Two Lands, was a primordial deity in Egyptian mythology.

“I am Atum, the creator of the elder gods

I am the one who gave birth to Shu

I am the great He-She

I am the one who did what seemed good to do

I seized the space in the place of my will

Mine is the space of those who advance

In the paths of the serpent circles.”

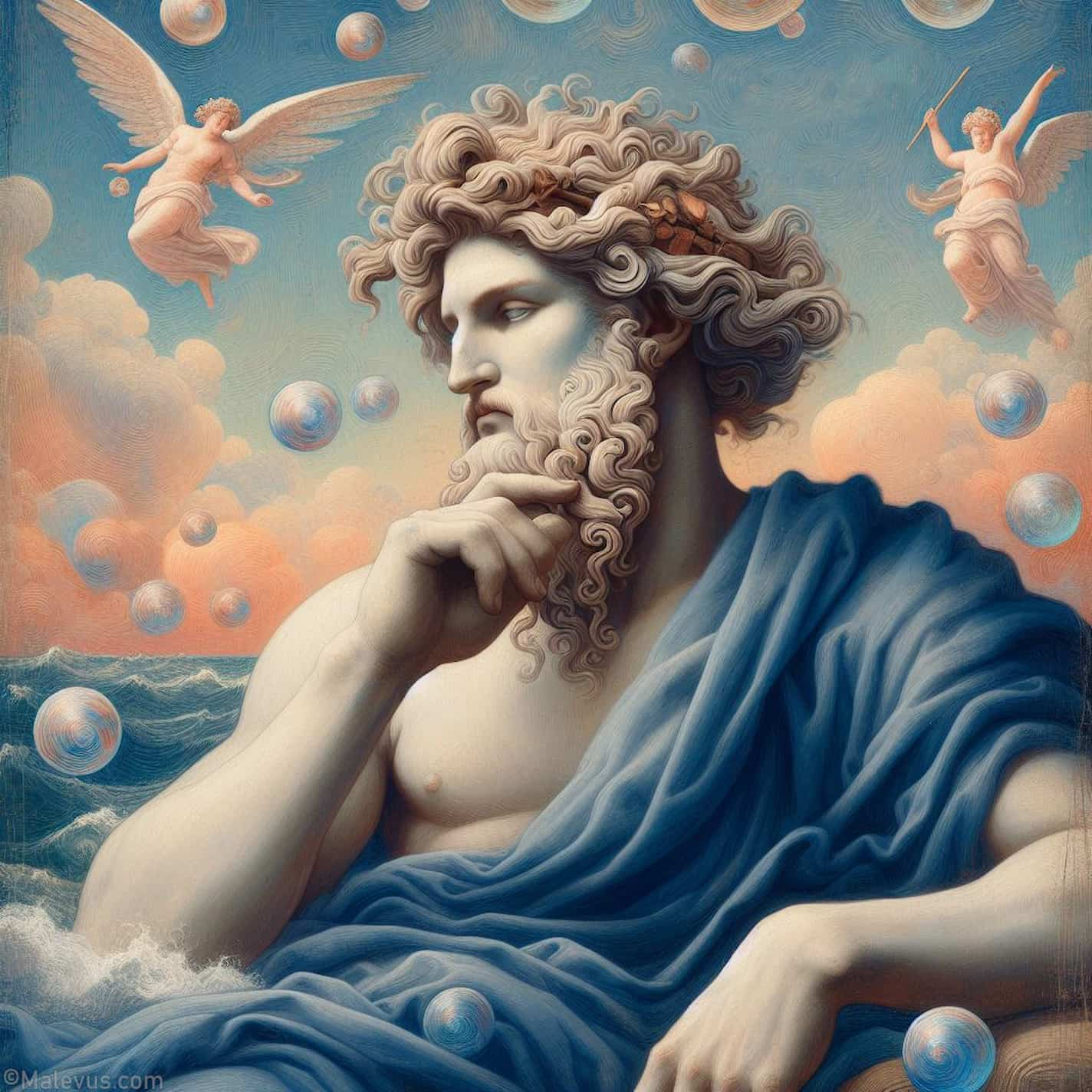

The names Atum, Tum, Atumu, and Tumu (Neb-er-djer), according to the theologians of Heliopolis, mean “the complete one.” It is believed that Atum created himself from the primordial waters of Nun, either by the power of his will or by uttering his name, thus using the magical power of speech. He was also called the “Lord of the Limits” or the Universal God. He was the founder of the Heliopolitan Ennead and often bore the epithet “Bull of the Ennead,” a possible reference to his zoomorphic worship of the bull Mnevis.

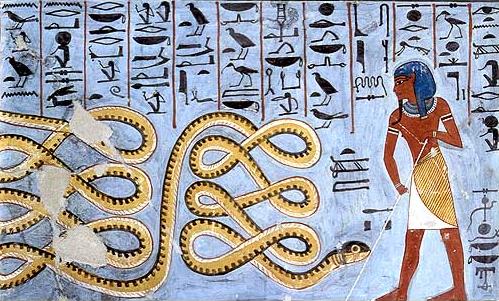

Sometimes Atum is considered not only to have originated as a serpent from Nun but also to return there in the same form. However, when the priesthood identified him with Ra (Re), the serpent turned into his adversary, as evidenced by his beastly depiction of a serpent’s head. According to tradition, when attacked by a serpent, he transformed into a serpent to devour it.

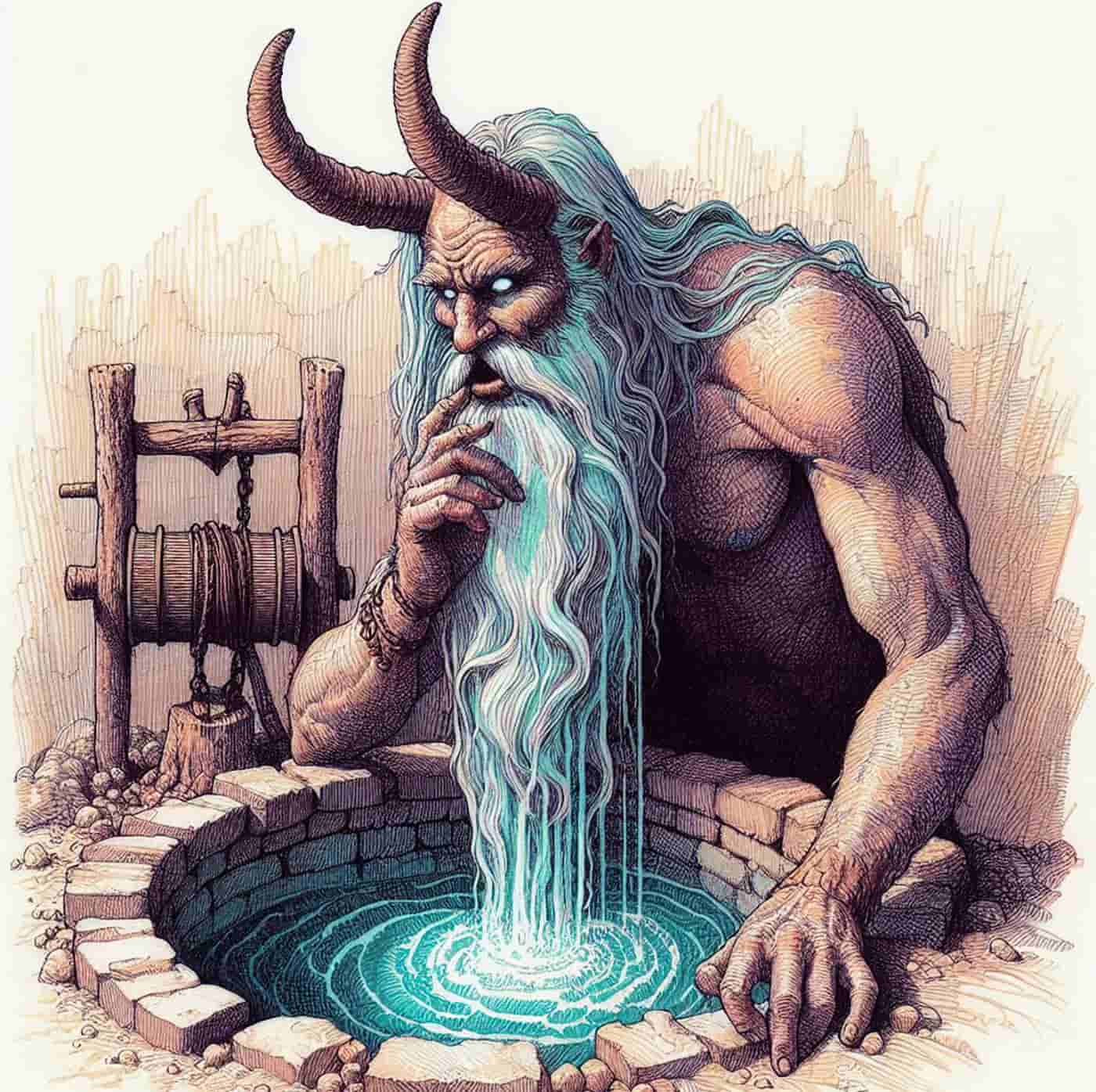

Nun, from whom all things originate, is the deity of chaos, the primordial ocean, in which were contained before creation the seeds of all things and all beings. In the Pyramid Texts, he is called the “father of the gods,” although he remained a simple spiritual creation, never acquiring a temple or any kind of worship. He is depicted semi-submerged in water, with his hands raised in the air, holding the gods who were born from him.

The aspect of Atum emerging from the primordial chaos as a hermaphroditic being and the creation of Shu and Tefnut are recounted in two versions. The earlier one, belonging to the Pyramid Age, describes how Atum takes his phallus in his hands and experiences orgasm, creating the pair with his semen.

An excerpt from the Brehmer-Rhind papyrus states:

“All the manifestations came into being after I developed…neither the sky nor the earth existed…I created from my own existence…my fist became my wife…and I created…Shu and Tefnut…then Shu and Tefnut created Geb and Nut…Geb and Nut created Osiris…Set, Isis, and Nephthys…They ultimately created the population of this earth.”

Symbols

The name Atum seems to derive from a root meaning “I do not exist” and “I am complete.” This god, as the local deity of Heliopolis, had the bull Mnevis as his sacred animal. However, from ancient times, his priests equated him with Re, the great solar god, teaching that within Nun, before creation, lived “a spirit, still shapeless, inherently carrying the whole of existence,” Atum. One day, this spirit manifested itself as Atum Re and created, from its essence, the gods, humans, and all beings.

Later, Atum became the personification of the sun, at sunset and before sunrise (as Nefertum, that is, young Atum), while his worship, combined with that of Re or Ra, expanded throughout ancient Egypt. Generally, Atum was considered the progenitor of the human race and was always depicted with a human head adorned with the “pschent” (double crown) of the Pharaohs. Initially a solitary god, he was regarded as the generator, without the assistance of any female principle, of the first divine couple, as we saw above. Later, they gave him a wife, and in some regions, two, because in Memphis he was sometimes linked with Iousas (Jousas) and sometimes with Nebet Hotep, from whom he had twins, Shu and Tefnut.

Iousas, or Iousaa set, is referred to as his shadow (also Aousaas in Greek Saosis) and means the great, the one who projects, strangely reminiscent of the Aousos, the dawn goddesses of the proto-Indo-European pantheon. Consequently, Iousaa set is the mother and ancestor of the gods. The power, endurance, and healing properties of the acacia became her symbols. In this theogonic myth, the acacia is the tree of life and the oldest of its kind, north of Heliopolis, which is said to be the birthplace of the gods. It is therefore natural that the tree of life was attributed to Atum’s companion.

Cosmogonic Narratives

Funerary literature preserves two well-known stories of the creation of Atum. One originates from the Heliopolitan tradition, and the other from Hermopolis. Both texts believe that the primeval earth emerged from the waters of primordial chaos (Nun). In the Heliopolitan tradition (PT 600), the solar god Atum stood on the primeval hill and brought into existence a second generation of gods, the god of air Shu, and the goddess of moisture Tefnut, and then continued with other acts of creation. In another version we examined earlier, the two gods are the product of Atum’s masturbation. This primeval hill where these creative acts took place was the future site of the Heliopolis temple and highlights the uniqueness of the god in the Egyptian pantheon. The myth continues with Atum inviting all the gods of Egypt to protect the pharaoh’s pyramid and restore life to him at a posthumous elevation. Clearly, here the pyramid symbolizes the primeval hill, and with the creative power of Atum and his myth, it becomes the suitable abode for the new life that emerges after the pharaoh’s death.

Our access to the Texts of the Sarcophagi of the Middle Kingdom (TS 335) and the Book of the Dead (Chapter 17) reveals the evolution of the cosmogonic myth. Although New Kingdom elements infiltrate the texts, the basic primary symbols of the chapters remain the same. In the New Kingdom, Atum – identified with the god Ra – again brings himself into existence from the primordial chaos (Nun) and begins creation from his position atop the primeval piece of land, the hill symbolized by the pyramids. Instead of creating Shu and Tefnut, however, as in the Heliopolitan tradition, in this text, he creates the Ennead (the major gods of Egypt) by naming parts of his body. The one, the primeval, becomes many, parts of the same god.

As in the first myth of Atum, the use of a creation myth in ritual reveals the myth’s power to recreate life for the dead. The difference in the text from the Heliopolitan tradition lies in the fact that it mentions the place of the primeval hill not as Heliopolis, but as the inner sanctum of the temple of Hermopolis. This is natural as there is evidence for other sanctuaries that similarly claimed precedence, such as Memphis and Thebes. Religious authority seems to have always been intertwined with political power.

At this point, it is possible to make two comparisons between the Egyptian and the biblical narrative of cosmogony. First, the myths of Egyptian cosmogony refer to a land separated from the primordial waters and the creation of an order capable of sustaining life. These themes certainly resemble the Genesis creation myth (Chapter 1), but the direct connection most researchers attempt between Genesis and Mesopotamian and Egyptian traditions is not so easy, lacking fundamental comparative elements. The second comparison, more documented, is the tendency – in both cosmogonic narratives – to link sacred temples with significant events of the past. Just as the Egyptians associated their temples with creation, so did the Israelites associate their temple in Jerusalem with Abraham’s sacrifice (cf. Genesis 22; Chronicles 2, 3:1) and David’s sacrifice for the protection of Jerusalem from destruction (Samuel 2, 24).

Memphitic Theology

In the cosmogonic myth of Memphis, the archaic tradition that attributed the creation of the world to Atum was challenged. Creation was attributed to the patron god of Memphis, Ptah. The text, also known as the Shabaka Stone, is attributed to the Nubian king Shabaka (716-702 BCE), who claimed to have discovered an ancient copy of the text, from which he copied it. Although some researchers believe this tradition predates Shabaka by two millennia, most assume that Shabaka’s discovery of the text in the 8th century was simply a fabrication, a scheme aimed at legitimizing Ptah as the older god. Nevertheless, in the myth itself, unlike the Atum myth, the primeval waters and the primeval hill do not precede the appearance of Ptah, as the god appears as a fusion of two other deities, Tatenen (god of the primeval hill) and Nun (as Ptah-Nun, primeval waters).

Ptah’s first acts of creation included the creation of Atum and the other eight members of the Ennead. This happened when Ptah expressed his thoughts in verbal forms, thereby introducing the concept of the creative power of speech, as in Genesis. It seems that those who composed the myth knew they were engaging in a radical theological renewal. While the Ennead of Atum came into existence from Atum’s seed and fingers, the Ennead of Ptah came from his lips and teeth, with which he uttered the names of all created beings. According to Memphitic theology, a result of the creative process was that Ptah now participated in the bodies and speech of the gods. He was present in every body of all living creatures on earth. However, the shortcomings of this particular myth in terms of its theological details, as well as its deficiencies regarding the origin of humanity, indicate that it is a later construction, aimed simply at emphasizing Ptah’s primacy in the succession of gods.

Not content with interpreting the phenomena of the external world, the priests of the major temples engaged in the composition of various cosmogonic systems concerning the successive appearance of the gods and the creation of the world. From these systems, the best-known are those taught in the major religious centers of Hermopolis, the Heliopolis of Memphis, and the city of Busiris. In each of these temples, the priests attributed the work of creation to the local god. Atum, Atum-Ra, Ptah, and Osiris, each in their respective temples, had been proclaimed creators of the world with equal titles, but as it appears from the above, not in the same ways of creation. In Memphis, people believed that the other gods emerged from the creator’s mouth and that everything was created from his voice, but in another sanctuary, such as Heliopolis, they believed that divine beings were born from a sneeze, the spitting of the creator, or from his masturbation. Of course, in all myths, humans are molded from the sweat or tears of the god or, together with other animals, from the dried mud of the Nile.

The Protection of Pharaohs

Atum, as the creator of all things and existences, protects the deceased from all dangers and negative forces of the Underworld. He defeats the serpent Nehebkau by pressing his finger on its spinal column and annihilates the serpent Apophis. In the tombs of the New Kingdom period, Atum is depicted punishing his enemies by decapitating them. Thus, no one could be more suitable for the protection of the pharaohs. Atum was considered the protective deity of the kings of Egypt and was regarded as the father of many successive pharaohs. During the Pyramid Age, it was Atum who elevated the deceased king from his pyramid to the sky to become a star god.

In later times, Atum protects the deceased pharaoh during his journey in the Underworld.

Atum also participated in the coronation ceremony of the king, thus providing a kind of divine legitimacy to the ruling dynasty. Reliefs in the temple of Amun depict Atum leading the king. As the supreme creator, Atum transfers his creative abilities and powers to the pharaoh, those which originate from the celestial bodies of his palaces, in the form of the Living Horus.

“Oh Atum-Khepera! You have become high, raised as the stone of Benben in the Palace of the Phoenix (Heliopolis).”

Sacred Animals and the End of the World

Atum, besides his primary anthropomorphic representation, in later periods took on the forms of the scarab beetle, the bull, and the lion. Among the animals belonging to primitive epochs of earthly evolution, the Egyptians chose the Ichneumon as Atum, a lizard, indicating its primordial reptilian origin. This particular symbolism is of special interest as it touches on a rather unusual and little-studied concept of Egyptian mythology: the idea of the end of the world.

There is a dialogue between Atum and Osiris in the Book of the Day, where Atum states that he will sink the world and all its deities, humans, and all other creatures into the primordial waters of Nun and that only he and Osiris will survive in the form of reptiles. Another story mentions a primordial catastrophe that ended with only one survivor, the snake Kerchet, a reminder of the snake’s ability to emerge renewed after shedding its skin. There is a cyclical perception of the flow of evolution towards destruction and regeneration, possibly an early version of the cycle of the evolutionary process.

Atum in the Later Hellenistic World

E. Grzybek, presenting an interesting analysis of the offerings of Ptolemy II to the god Atum recorded in a column, considers that the large number of references to Atum as the father of Ptolemy II are rather a determination of Ptolemy I himself than of the god Atum. He believes that the iconographic element of the double crown of Egypt indicates that the constant references to Atum are in fact references to Ptolemy I, the father of Ptolemy II.

M. Minas, on the other hand, notes that Atum everywhere bears the double crown in his iconography, and this means that the column does not only specify Ptolemy I with the name Atum, but the royal quality is replaced in many cases with the divine quality, as it is a stereotype in Egypt to call the pharaoh the son of god.

In any case, what is indicated by the reference to the god, either as a Pharaoh claiming his divine origin or as a god, is the long-lasting presence of Atum in the pantheon of forces that played a dominant role in the long history of Egypt. In one way or another, the primordial Atum arrived in the Hellenistic period transformed but still vigorous.