Under his real name, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavius, Augustus was the first and most famous Roman emperor. When his uncle Julius Caesar died in 44 BCE, Octavius began a long political struggle to gain power. In 31 BCE, he won the naval Battle of Actium against his main rivals, Mark Antony and Cleopatra, Queen of Egypt.

Upon returning to Rome, Octavius laid the foundation for a new regime in 27 BCE: the Principate. Now called Augustus, he gradually accumulated all the powers, thus laying the foundation for the Roman Empire. His reign was marked by peace and prosperity, particularly in the arts, and this period is known as the “Augustan Age,” considered the golden age of Roman classicism.

Octavius: Caesar’s Heir

The future Augustus was born Gaius Octavius on September 23, 63 BCE (the year of Cicero’s consulship), in Rome, on the Palatine Hill. His father served as governor of the province of Macedonia until 59 BCE and died upon his return in 58. Octavius barely knew him, and his mother took on a significant role in his life. Atia Balba Caesonia, his mother, was the niece of Julius Caesar. The young Octavius was then under the tutelage of Gaius Toranius but also under the protection of his maternal grandmother, Julia.

Thanks to her, he was educated until age twelve by some of the greatest masters of rhetoric. It was during this period that he formed important friendships, such as with Agrippa, who would later play a crucial role in his life. While Octavius excelled in politics, he was not particularly skilled in military affairs. Agrippa, a brilliant strategist on both land and sea, would act as his right-hand man in military matters.

Rome’s political situation was becoming increasingly tense, with the rivalry between Caesar and Pompey as the backdrop. Octavius soon aligned himself with his great-uncle and played a political role alongside his sister in the unfolding intrigues. In 48 BCE, Caesar admitted Octavius to the college of pontiffs, and by 45 BCE, he was already on a military campaign in Spain against Pompey’s supporters. During this time, his first health problems emerged, and he especially struggled to present himself as a capable military leader, unlike his friend Agrippa. In the same year, Julius Caesar, who had no sons, named Octavius as his heir in his will, leaving him three-quarters of his wealth.

Upon Caesar’s assassination in March 44 BCE, Octavius was in Apollonia, and his life was at risk. However, against his mother’s wishes, Caesar’s heir decided to return to Rome to assert his rights. He was only nineteen when he arrived in Brindisi and chose to be called Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, or Octavian. Determined to play a central role in resolving the ongoing civil wars, he sought to avenge his adoptive father’s death.

The Civil War

As Caesar’s legitimate heir, Octavian initially positioned himself as a rival to Mark Antony, who was popular with the Roman people and saw himself as Caesar’s natural successor. However, through his political acumen and with the military support of his allies (particularly Agrippa), the future Augustus gradually marginalized his rival. Octavian benefited from Cicero’s support, which aimed to help him secure the Senate’s decisive backing. Antony was defeated at Modena in 43 BCE, and both sitting consuls were killed. Cicero had planned to share the consulship with the young Octavian, but the Senate refused.

This was a significant moment in the early political career of the future emperor, as he began to see the Senate as his main adversary. The senators did not welcome the rise of a young man who might become another Caesar. However, Octavian eventually secured the consulship and organized the punishment of Caesar’s assassins.

By the end of 43 BCE, Octavian had gained the upper hand over his opponents and, after tough negotiations, secured the alliance of Mark Antony and Lepidus, forming the Second Triumvirate.

The time had come for Caesar’s assassins to pay: they were hunted down the following year and defeated at the Battle of Philippi. The main conspirators, Brutus and Cassius, committed suicide. The triumvirs then divided control of the Roman world, not yet an empire. The last threat, Sextus Pompey, was crushed in 36 BCE.

However, the peace did not last long, as rivalry continued between Antony and Octavian, despite Antony’s marriage to Octavian’s sister. Octavian’s popularity grew, while Antony increasingly came under Cleopatra’s influence. Lepidus was quickly sidelined, and his African provinces fell into Octavian’s hands. War eventually broke out between the two heirs of Caesar, culminating in the naval Battle of Actium in 31 BCE: Antony and Cleopatra were defeated, and Octavian became the sole ruler of Rome.

The Beginnings of Augustus’ Principate

As early as 38 BC, Octavian obtained the title of Imperator; but his victory over Antony allowed him to accumulate titles, and therefore power: Princeps Senatus in 28 BC (that year, he completed his sixth consulship, with Agrippa as colleague). The Senate gave him the honorary title of Augustus in 27 BC, the tribunician power in 23 BC, and his imperium was renewed for ten years. Although not officially declared, a new regime was established to replace the Republic: the Principate.

Despite his speeches emphasizing the importance of the Senate and the people, Augustus was clearly the sole decision-maker. He then initiated reforms: in the army, administration, organization of the provinces, as well as significant public works in Rome. He shaped what would become the Roman Empire for centuries to come.

A strict observer of Roman virtues, Augustus strove to regulate public morals by enacting sumptuary laws (limiting expenditures) and natalist laws (encouraging marriage). In the economic field, he promoted the development of agriculture in the Italian peninsula. His religious policy had two aspects: on the one hand, Augustus worked to restore and renovate traditional religion, and on the other, he founded the imperial cult.

A protector of the arts, Augustus was a friend of poets such as Ovid, Horace, and Virgil, as well as the historian Livy, to whom he extended his support and generosity. With the help of his friend and advisor, Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, Augustus sought to embellish Rome by constructing the Forum of Augustus, the Theatre of Marcellus, the Temple of Apollo Palatinus, the Pantheon, and the Baths of Agrippa. According to Suetonius, “he left a Rome of marble where he had found a city of bricks.”

Augustus in Gaul

While Caesar had formed only one province in Transalpine Gaul, Augustus, taking into account the ethnic subdivisions of the region, divided it into four areas. In 22 BC, the former Province, bounded by the Rhône and the Cévennes, was renamed “Narbonensis” and became a senatorial province governed by a proconsul. The rest of Gaul, called Gallia Comata, was divided into three regions, each governed by a legate: Aquitania, between the Loire and the Pyrenees; Lugdunensis, between the Loire, Seine, and Saône; and Belgica, east of the Saône and north of the Seine.

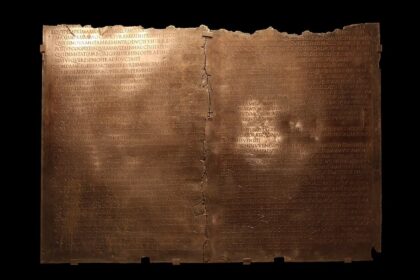

The former Roman colony of Lugdunum, founded in 43 BC, became the capital of the Roman province under Augustus and the starting point of the five major imperial roads leading to Aquitania, Italy, the Rhine, Arles, and the Ocean. The emperor built the Amphitheatre of the Three Gauls there, dedicated to his cult and that of Rome, as well as a mint. Augustus visited the province at least four times, taking particular care to pacify it, while his friend and son-in-law Agrippa personally oversaw the administrative organization of the region by conducting a complete land survey of Gaul and constructing an extensive road network.

Despite the pacification efforts initiated during the last years of Julius Caesar’s dictatorship, some tensions persisted locally, and several outbreaks of violence revealed the last remnants of rebellion by certain Gallic peoples against Roman domination. The Aquitanians (in 39 BC), the Morini (in 30 BC), the Treveri (in 29 BC), and the Aquitanians again (in 28 BC) revolted, prompting the intervention of Roman legions.

In 25 and 14 BC, Augustus subdued the peoples of the upper valleys of the Alps, and in 6 BC, a trophy was erected at La Turbie to commemorate his victory over them.

A Difficult End to His Reign

Internal peace did not necessarily mean peace with Rome’s neighbors. Augustus had to address, and often relied on the talented Agrippa to suppress, various threats around the Empire. The goal was primarily to consolidate the borders rather than expand Rome’s territory: he fixed the limits of the Empire at the Euphrates, facing the Parthians, and pushed the northern borders to the Danube. However, he suffered a traumatic setback in AD 9, when the legate Varus and three legions were massacred by the Germans. Tiberius then took over, but Augustus had to accept that the border would remain on the left bank of the Rhine.

His reign became increasingly painful: his health problems were compounded by conspiracies (such as Cinna’s, from 16-13 BC), and especially by succession issues. Despite several marriages (including his last with Livia), Augustus had no surviving sons.

He adopted Agrippa’s sons, Gaius and Lucius, in 17 BC, but they died before him. He eventually adopted his stepson Tiberius, Livia’s son, in AD 4.

Additionally, Augustus saw his friends and companions, such as Agrippa, Maecenas, and Drusus, die before him. Thus, he passed away almost alone on August 19, AD 14, and was deified the same year, as he had previously deified Caesar. Upon Augustus’ death, Tiberius, who had married his daughter Julia, succeeded him.

Legacy of Emperor Augustus

Historians, both ancient and modern, have expressed varied opinions about Augustus. Some condemned his ruthless quest for power, particularly his role in the proscriptions during the triumvirate era. Others, like Tacitus, who critiqued the imperial regime, acknowledged his achievements as a ruler.

Modern historians sometimes criticize his unscrupulous methods and authoritarian style of governance, but they generally credit him with establishing an efficient administration, a stable government, and bringing security and prosperity to what would become the Roman Empire. His authority over the provinces and military power ensured the Pax Romana, or “Roman Peace,” in an empire spanning the entire Mediterranean, Asia Minor, and almost all of Western Europe.

It was during the “The Age of Augustus” that the historian Livy published his History of Rome from its Foundation.

Emperor Augustus: FAQ

The Education of the Future Emperor Augustus

Augustus received a classical education typical of the Roman elite of his time. He studied literature, rhetoric, philosophy, and the arts. Caesar ensured he received a solid education to prepare him for a political career, along with thorough military training. This education and Julius Caesar’s influence helped prepare Augustus for his future political career.

The Various Names of Octavian

Octavian, or Emperor Augustus, had different names reflecting various stages of his political career and life. These are the names used to refer to Augustus:

- Gaius Octavius Thurinus (his birth name)

- Gaius Octavius (family name without title)

- Gaius Octavius Caesar (after his adoption by Julius Caesar)

- Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (after his adoption by Caesar)

- Octavian (commonly used to distinguish him from his rival Mark Antony during the Second Triumvirate)

- Imperator Caesar Divi Filius (official title as the first Roman emperor)

- Augustus (honorary title received in 27 BC, meaning “venerable” or “sacred,” which gave him the name Augustus that we know today)