It looks like human nerve cells include a previously unidentified form of synapses. These neuronal junctions are not found at the more well-known nerve processes, but rather at the cellular level, in small hair-like cilia. The team describes its findings in the scientific journal “Cell,” describing how activation of these synapses by neurotransmitters like serotonin produces changes directly in the cell nucleus, which may affect the DNA’s interpretation. In other words, the newly discovered axo-ciliary synapse set off a chain reaction in the nucleus that affects how DNA is read.

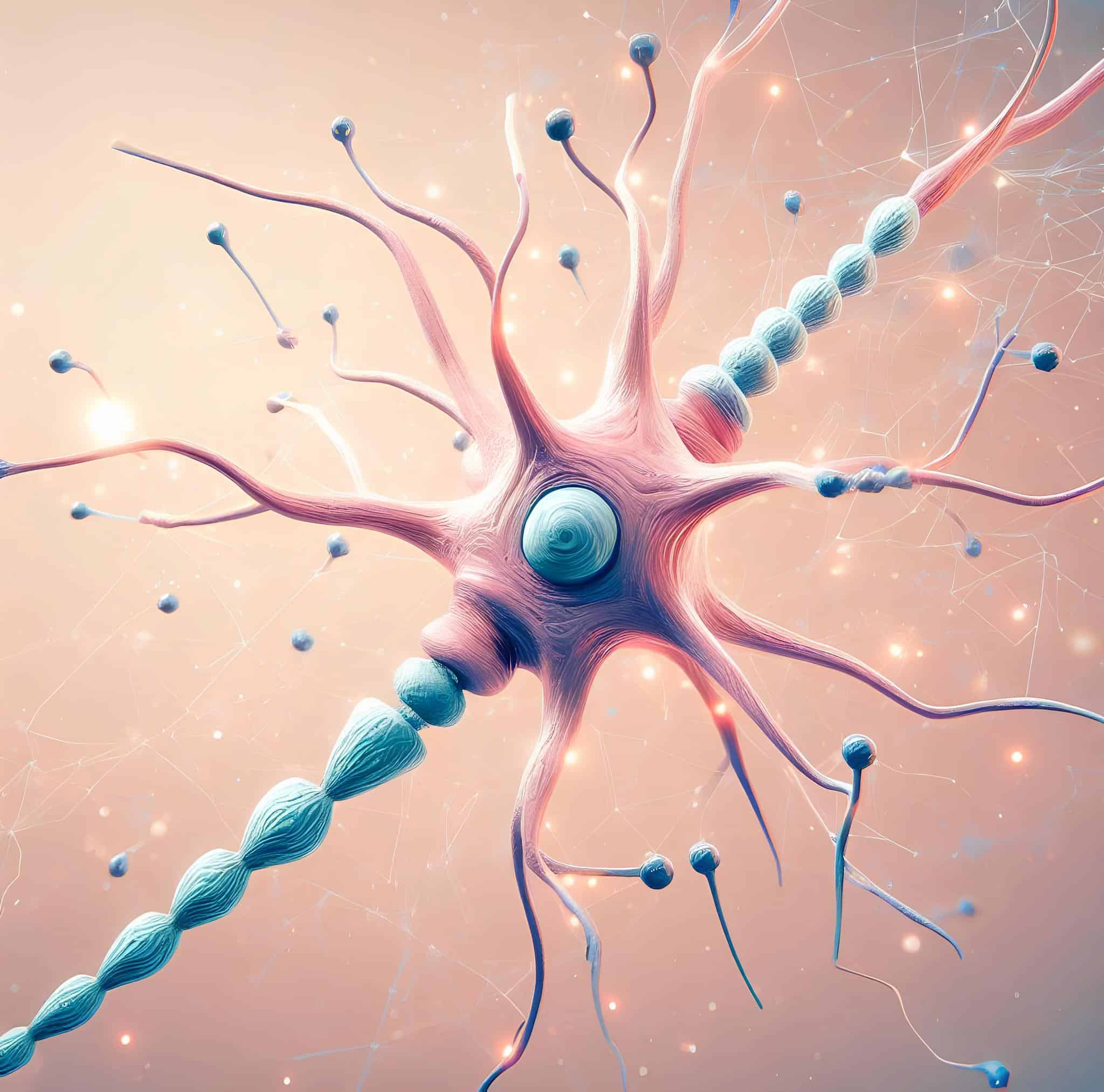

Synapses, or connections, between nerve cells are often thought to be found at the cellular bodies’ long extensions, known as axons. These are the longer, branching extensions of a cell that send neurochemical impulses to the shorter, root-like dendrites of the next cell. Neuronal electrical impulses activate vesicles stored at axo-dendritic switch points, releasing neurotransmitters. These chemical messengers travel through the axon to the dendrite, where they attach to receptors and set off electrical impulses in the receiving cell.

Cilia: a biological mystery

However, it has now come to light that this widespread perception is in fact misleading. Researchers from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute in Boston, led by Shu-Hsien Sheu, found a new form of synapse on neurons. The researchers set out to better understand the primary cilia that are found in a subset of our cells. These primitive cilia, which project just a few micrometers from the cell, are the functional equivalent of the flagella of our single-celled ancestors.

The cilia play a crucial role in the movement and transport of some cells in our bodies, such as those of the respiratory system and the sperm. Furthermore, they are essential for cell division but are afterward destroyed in most cells. Because most neurons in the adult brain no longer divide or differentiate, it is unclear what role primary cilia play at this stage of brain development. However, they are still found in the vast majority of brain cells, including neurons and glia.

Interaction of cilia with axons

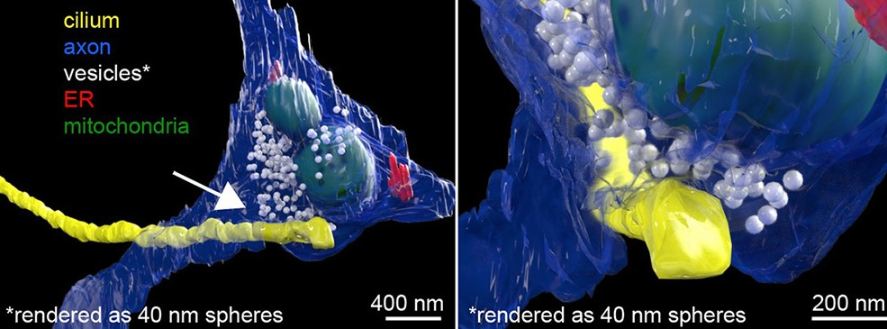

The study team employed an advanced kind of electron microscopy called a focused ion beam-scanning electron microscope (FIB-SEM) to get a better look at the synapses. Here, ions are used instead of electrons to perform the scanning. Sheu and his colleagues analyzed these cell extensions and their contact locations in nerve cell cultures from the human and mouse hippocampus by using antibodies that selectively dock to the cilia.

The findings were unexpected, showing that the cilia of around 80% of brain cells did not just extend into the open extracellular space but also contacted the axons of nearby cells. This prompted the thought experiment of whether or not these cilia on neurons really made specialized connections with axons and served as neuronal information transfer hubs. They employed specific biomarkers to look for signs of synaptic vesicles and other structures at these interfaces.

An unheard-of synaptic junction

Analyses showed that the junctions between cilia and axons were quite similar to synapses. There are vesicles in the axons, and some of them are docking or fusing with the plasma membrane, suggesting that chemicals are being released. Serotonin is transported from the axon to the cilia in around 36% of the contact locations seen, as shown using fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM).

This discovery is completely altering the dynamics. The team is calling their discovery an “axo-ciliary synapse” or “axon-cilium” synapse, a previously unknown form of synapse between neurons. It has been discovered that the neurons make connections from the axon through the cilia all the way into the interior of the nerve cell, rather than only at the switch points between dendrites and axons.

Manipulating nerve cell gene expression

Moreover, these newly found synapses are more functional than others. These contact points do not only create electrical impulses in the recipient cell as typical synapses do; they also set off a chain reaction in the nucleus of the cell that alters histones and chromatin, the “packing” of genetic information that profoundly affects how DNA is read. There are numerous cellular features that are shaped by chromatin. This synaptic structure is an example of a signaling route that may modify gene expression by affecting what is transcribed in the nucleus. So, the newly found axo-ciliary synapse leads to long-lasting alterations in gene and cell activity that may endure for hours or even years, in contrast to the transient stimulus of typical synapses.

Molecular radio dish located in the nucleus of a cell

Scientists note that their findings demonstrate a previously unknown mechanism by which neurons process and react to their surroundings and external inputs. To put it another way, the synapses in the cilia operate as the “antenna of the cell nucleus,” allowing inputs to have an immediate impact on gene activity inside the cell. The primary cilia‘s potential role as an epigenetic regulator that modifies the transcriptional program in response to external cues is fascinating.

The next step for the study team is to determine whether or not the newly found axo-ciliary synapses react to other neurotransmitters besides serotonin. Analyses have shown that the cilia of brain cells include receptors for seven to ten additional neurotransmitters. Whether cilia in tissue cells other than the brain also serve a signaling role is likewise unknown.