Carthaginian theology revolved around the god Baal Hammon (also spelled Ba’al Hammon, Baal Hamon, Ba’al Khamon, and Baal-Hammon). Phoenicians spelled his name 𐤁𐤏𐤋 𐤇𐤌𐤍 in Punic and it is believed to mean “lord of a multitude.” However, the name Baal Hammon has also been translated by academics to mean “Lord of the Brazier” or “Lord of the Altar of Incense.” This is in line with the Brazen Bull torture device of the Ancient Greeks which was designed to raise a fragrant cloud of incense.

Who Was Baal Hammon?

Moloch, who also demanded child sacrifice, was similar in features to Baal Hammon. He was a Canaanite deity with a bull-headed idol. But it was not solely practiced among the Phoenicians or their Carthaginian cousins.

Often referred to as the “African Saturn,” Baal Hammon presided over the heavens, storms, dew, flora, and fertile ground. He ruled the gods and was the Carthaginian goddess Tanit’s masculine partner, or consort. His characterization as the “African Saturn” by the Romans suggests that Hammon was seen as a fertility deity in his Romanized version.

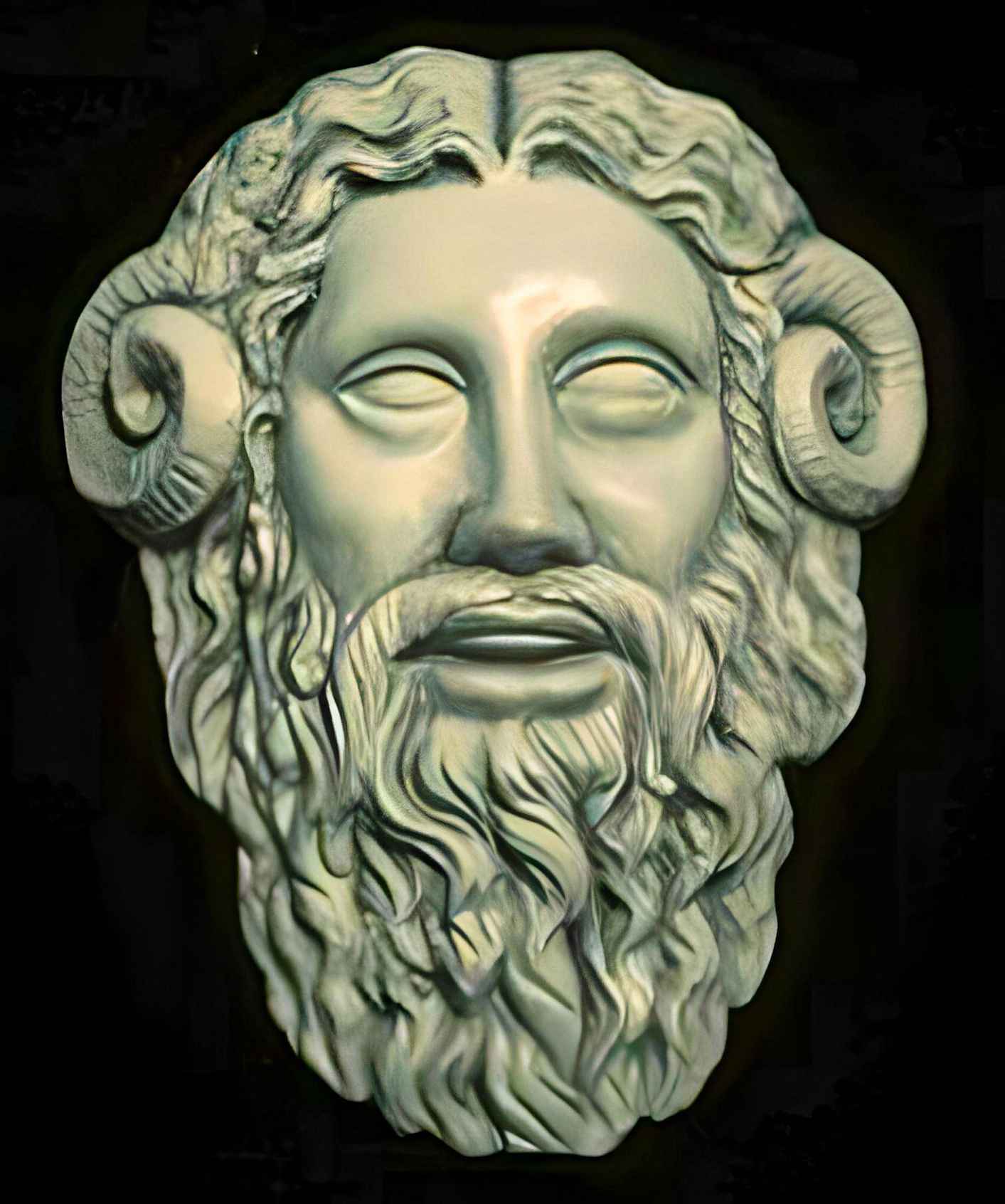

The term “Lord of the Two Horns” refers to the common depiction of Baal Hammon as a bearded elderly man with ram’s horns (Ba’al Qarnaim). He was often shown as a strong, elderly figure with a beard, dressed in long robes, and seated on a throne adorned with cherubs.

A pinecone or ears of corn topped the hilt of his staff, and a solar disk, sometimes adorned with wings, was often shown next to his head, similar to Egyptian bas-reliefs. The pinecone symbolized immortality and male fertility.

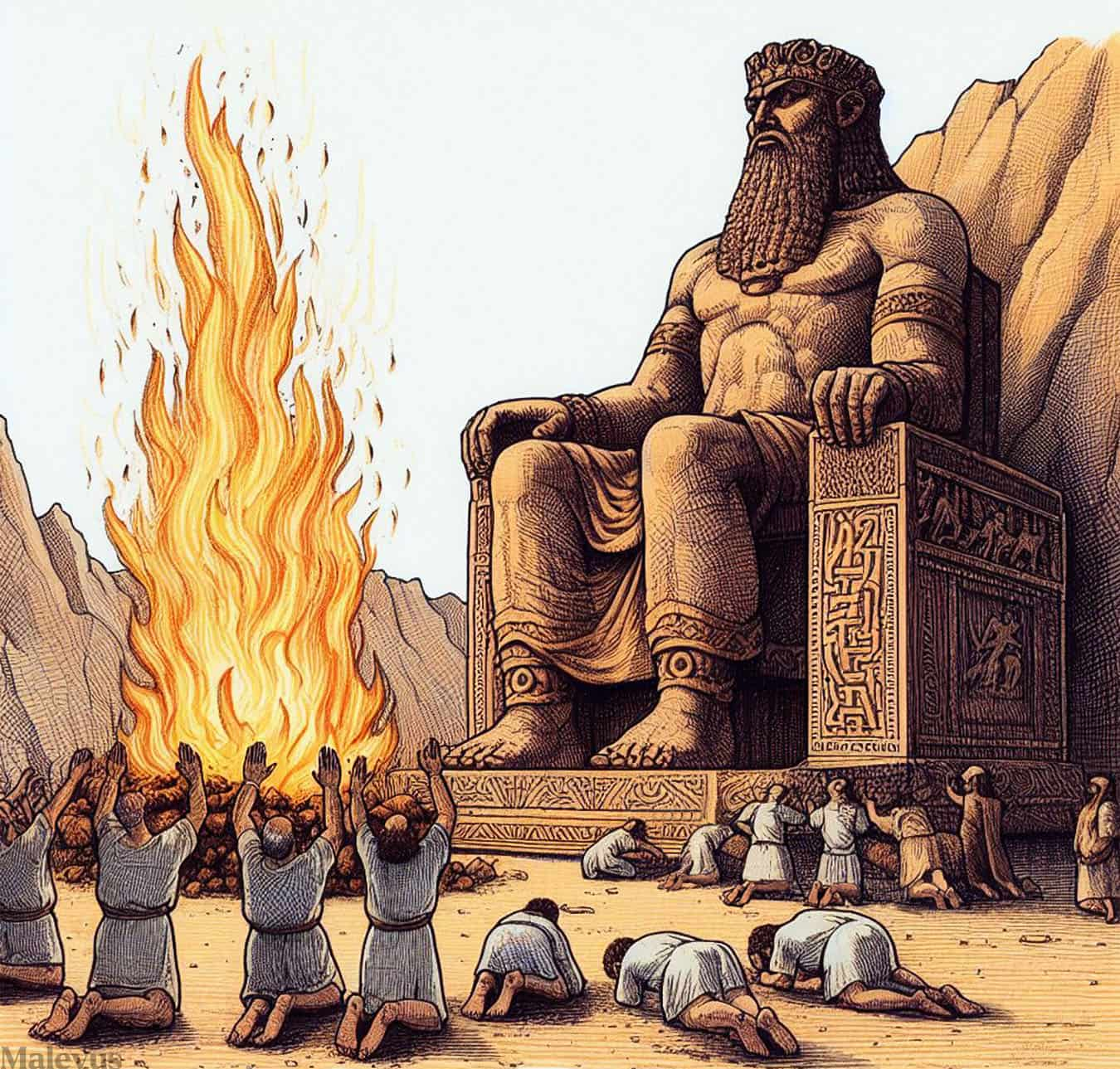

According to Greek and Roman accounts, the Carthaginians performed child sacrifices by setting them on fire in honor of the god Baal Hammon.

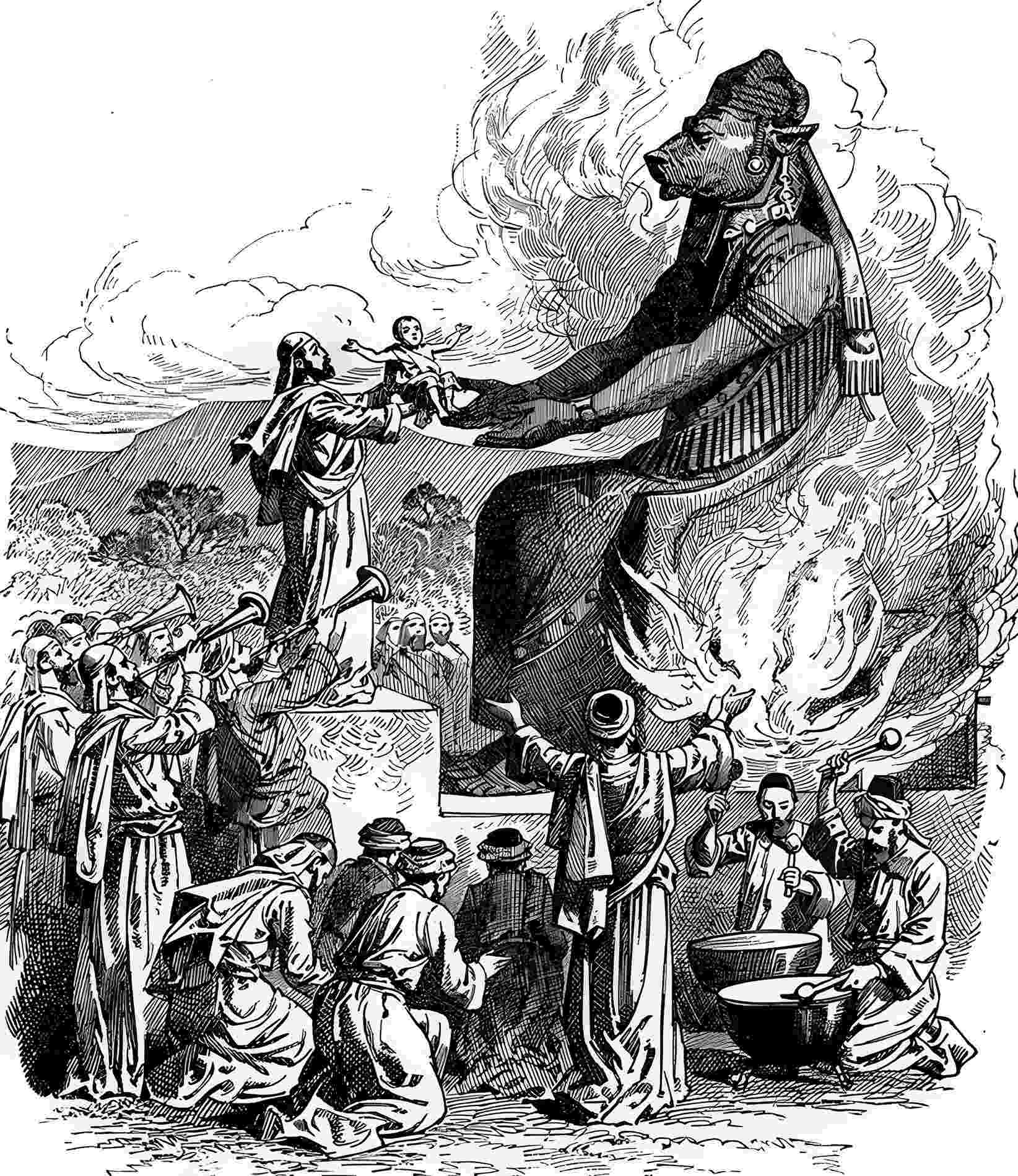

Some ancient writers claimed that he was worshiped through the practice of child sacrifice as part of the molk ritual. According to the historian Diodorus, the giant bronze statue of Kronos (Baal Hammon) in Carthage was said to have long arms reaching the ground, and sacrifices were placed in its hands and lowered into a fiery pit.

Other Phoenician and Carthaginian colonies in the western Mediterranean also honored Baal-Hammon, and his followers’ devotion to the god persisted throughout Roman-era North Africa.

Origin of Baal Hammon

Baal Hammon was a god with Syro-Phoenician roots who was probably worshiped as early as Ugarit (c. 6000–c. 1185 BC) and whose name is documented in inscriptions from Palmyra dating back to at least the 1st century BC. In Palmyra, he was associated with Baal, the supreme deity of the oasis.

It is believed that the worship of Baal at Tyre was the ancestor of the religion of Baal Hammon in the Phoenician colony of Carthage. There is a fundamental difference between the two since the Baal of Tyre was not revered as a supreme god.

Multiple recent studies have linked the Northwest Semitic deities El and Dagon to Baal Hammon. Baal Hammon’s prominence in Carthage makes him comparable to El, the most important deity in the Canaanite religion.

Two Phoenician inscriptions honoring El-Hammon were found in the remains of Hammon, today known as Umm al-Amad, between Tyre and Acre by Ernest Renan in the 19th century. It’s probable that El and Baal Hammon were interchanged, as El was often associated with Kronos, a Greek god.

The Belgian orientalist Edward Lipinski saw parallels between him and the ancient Canaanite deity Dagon, who was similarly associated with fertility.

It was after the Punic defeat at Himera in 480 BC that ties between Tyre and Carthage were reportedly broken. The cult of Baal-Hammon was brought by immigrants from Tyre in the 7th–6th centuries BC, and images of the god started to appear first in the 6th century BC. By the 5th century BC, Baal Hammon had risen to prominence among the Carthaginian gods.

Human Sacrifices to Baal Hammon

The Greeks and Romans believed that the Carthaginians burned their children as offerings to Baal Hammon. They performed this rite, known as molk, at temples called tophets (shrines), where they made offerings to Baal Hammon and other deities like Tanit in exchange for blessings or in fulfillment of promises.

Greek writers portrayed the custom as “bizarre” rather than horrifying, highlighting how commonplace it was.

The historian of Alexander the Great, Cleitarchus, writes in the 3rd century BC on this topic: “Out of reverence for Kronos, the Phoenicians, particularly the Carthaginians, promise one of their children, burning it as a sacrifice to the divinity if they are eager to obtain success.“

The historian Diodorus from the 1st century BC claims that a massive bronze statue of Kronos (Baal Hammon) existed in ancient Carthage. The arms of the statue extended far from its torso, palms facing up, and were thought to be attached to the body by a lifting mechanism. The sacrifice was put in his hands, and the idol dropped it into a pit of flame.

Plutarch states that after defeating the Carthaginians in the Battle of Himera (480 BC), the tyrant Gelon particularly stipulated in the peace treaty that the Carthaginians would no longer be allowed to sacrifice children to Baal Hammon. The Greeks were appalled by this practice.

In 310 BC, when the Greek tyrant Agathocles of Syracuse (361-289 BC) marched on Carthage, one of the biggest human sacrifices in history took place. The Carthaginians said that they had failed because they had abandoned their traditional religious practices and had, for a long time, sacrificed the offspring of strangers who had been purchased and covertly raised rather than their own.

While the hoplites of the tyrant approached the Punic city, more than 500 children were sacrificed as the army neared the gates. 200 children from aristocratic families were sacrificed, and another 300 children were committed to the sacrifice in will, all in an effort to quench the god’s anger.

Anthropologists found that 85 percent of children sacrificed to Baal Hammon were less than six months old. The first evidence of human sacrifice was discovered in the middle layer, dating back to the first quarter of the 7th century BC, where urns were being filled with the ashes of burned infants.

This coincides with the arrival in Carthage of a sizable population of people from the city of Tyre. In certain cases, lambs were substituted for children during the ritual. When asked how often human sacrifices were performed, Roman senator and poet Silius Italicus (c. 26–101 AD) said once a year.

More than 25 times in the Old Testament and in other Middle Eastern sources, we learn of child sacrifice in the Iron Age Levant. They provide substantial evidence for the colonial setting of a practice for which the existence of shrines in the West argues that it was much more ritualized.

Spread of the Cult of Baal Hammon in Other Cultures

According to the ancient Greeks, Baal Hammon was really the Titan Kronos. The Romans connected him to their god, Saturn. A major Roman religious event, Saturnalia, may have been impacted by cultural interaction with Carthage during the Second Punic War (218–201 BC).

Major changes to Saturnalia were made in 217 BC, when the Romans suffered one of their worst losses at the hands of Carthage in the Battle of Lake Trasimene. They had observed the festival in accordance with Roman practice up to that point. An attempt to please Baal Hammon motivated the establishment of new rituals during this period, including the Saturnalia.

His depiction in Hesiod’s “Theogony” is very similar to that of the Hurrite-Hittite deity Kumarbi, whom the Semites associated with the fertility deity Dagon. The Greeks, in the meantime, named him Kronos. In turn, the same deity was revered in Hellenistic times as Kronos and in Syria and Lebanon as Baal Hammon.

Saturn was also the fertility god in Italic mythology and Baal Hammon was addressed as senex (“old man”), frugifer (“fruitful”), deus frugum (“god of grains”), and genitor (“parent”) in Roman inscriptions.

Denarii (silver coin) of Clodius Albinus (150–197) bore Baal Hammon’s image. He was an insurgent for imperial authority in 193–197 who hailed from Hadrumetum in Africa Province. Baal–Hammon–depicted coins were struck in this area during the reign of Augustus.

Other Phoenician and Carthaginian colonies in the western Mediterranean also worshiped Baal Hammon. According to the Greek historian Strabo (63 BC—24 AD), there was a temple dedicated to Baal Hammon in Cádiz (Spain). It’s likely that this temple actually existed in Málaga (Spain) since coins minted there feature the temple’s picture above the inscription that reads šmš (“shamash”).

According to Augustine of Hippo (354–430), local pagans during the time he lived opposed their Saturn to Jesus, and the worship of Baal Hammon remained one of the most prominent in Roman-era North Africa.

Etymology of Baal Hammon

Terms like “lord” and “ruler” in Punic were expressed with the Punic word lb’l (Baal). Baal is an epithet of many Canaanite and Phoenician deities; however, this cannot be taken as proof of any kind of connection between all Baal gods.

“Crowd” or “multitude” is one possible meaning of the Hebrew/Phoenician word ḥmn (hammon). Ilya Shifman identifies him as a sun god which stems from the name’s etymological similarity to the word for “brazier” in Hebrew/Phoenician, ḥammān. This name might also be connected to the Egyptian deity Amun.

Hammon was also thought of as a moon deity, but only in Israeli archeologist Yigael Yadin’s eyes.

According to Frank Moore Cross, the Ugaritic and Akkadian people used the name Khamōn to refer to El, the deity of Mount Amanus in Syria and Cilicia (Turkey) who lived on the mountain. This is based on a description by the Ugarit people.

Many different meanings can be derived from the name. One of the first translations of the name was offered in 1883 by Joseph Halévy and it was Amanus or Amana. The first known use of this deity’s entire name was found on the eastern slope of the ridge at Zincirli Höyük, Turkey in 1902, in an inscription that dates back to about 825 BC.

Edward Lipinski argued that the name should be transcribed as “Baal-Hamon” since the doubling of the name occurred when worshipers in North Africa began to associate this god with Zeus (Jupiter) Ammon.

Images and Features of Baal Hammon

Immigrants from Tyre introduced the religion of Baal-Hammon to Carthage in the 7th and 6th centuries BC. Images of the deity appear in the traditional Persian style, depicting a strong, bearded elder in long garments, seated on a throne, and generally adorned with cherubs. Altars or bethels bearing his name date back to the 6th century BC.

Baal Hammon was associated with the ram. He was worshiped as Baal Qarnaim (“Lord of the Two Horns”) at Carthage and the rest of North Africa in an open-air sanctuary on Jebel Boukornine (“Mount of the Two Horns”). The sanctuary was located in front of Carthage Bay, and the same mountain resides in Tunisia today.

Baal Hammon was formerly mistakenly linked to Baal Melqart, a tutelary god from Tyre who has nothing to do with Hammon.

Around the middle of the 5th century BC, Tanit became revered alongside Baal-Hammon, creating a heavenly partnership with him. Archaeologists have discovered so many Tanit emblems in inscriptions, mosaics, ceramics, and stelae, leading them to believe that she became the most venerated divinity in Carthage beginning at this time.

This change in belief pushed Baal Hammon and Melqart into secondary positions. Despite this secondary role for Baal Hammon, Tanit’s primary appellation was still “Tanit, Face of Baal” (Tnt pn B’l in Punic). This is similar to Jesus being revered more often than God.

Later, in the 4th century BC, this feature of Tanit was documented in other Phoenician colonies (Malta, Motya, and Sardinia) as well. The pinecone has long been seen as a sign of immortality and male fertility, both of which point to Baal Hammon’s status as a fertility god and a sun deity.

The god’s throne, shown on a gem from the 7th or 6th century BC, rests on a boat that floats on the waters of the deep ocean, as shown by the plants’ downward-pointing stems. This portrays Baal Hammon as the ruler of the heavens, the earth, and the underworld.

Toponymy of His Name

Song of Songs 8:11 mentions Baal-Hamon, variously spelled Baal-Hammon and Baal Khamon, as the location of Solomon’s very successful vineyard.

Each caretaker was responsible for the vineyard and owed the king one thousand silver shekels. Baal-gad and Hammon, both referenced in relation to the tribe of Asher in Joshua 19:28, are thought to be in the same place.

Some people link him with Bellamon (Belamon) and place him in the Central Palestine town of Dothan. It is unknown whether or not these places have any connection to the divinity of Baal Hammon.

According to some academics, the name “Baal-Hammon” in the Bible is not meant to be seen as a location; rather, it is a metaphor for Solomon’s control over a large population, and its name is a play on the Hebrew phrase for “Lord of a multitude” (lbʻl ḥmn).

Modern Studies

Some researchers now think that during the molk sacrifice, the children might be killed first before the ritual instead of being burned alive.

Research that appeared in the 2010 issue of the archeology journal Antiquity further supports human sacrifice at tophets. However, the topic of Carthaginian ritual sacrifice was the subject of another essay published in the same magazine in 2012.

According to this later study, the teeth discovered at the archaeological sites would diminish at different rates depending on their mineralization. Consequently, this changed the assumed age of the remains, and it was concluded that the remains actually belonged to stillborn infants.

Therefore, the findings disproved the concept of human sacrifice in the tophets. However, two studies published in 2013 challenged this interpretation and justified the technique used from a historical and archaeological viewpoint.

References

- Song of Songs 8:11-14 – Bible.com

- Epigraphy of the tophet – José Ángel ZAMORA and Maria Giulia Amadasi – Academia.edu

- The Iconography of the Canaanite Gods Reshef and Baʻal – Late Bronze and Iron Age I Periods (C 1500-1000 BCE) – By Izak Cornelius – 1994 – Google Books

- Ancient Coins of the Graeco-Roman World – The Nickle Numismatic Papers – By Waldemar Heckel, Richard Sullivan – 2010 – Google Books

- (PDF) Romanizing Baal: the art of Saturn worship in North Africa – By Andrew Wilson – Academia.edu