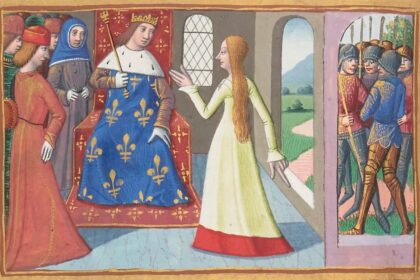

King Philip Augustus of France (Philip II of France) led his army into combat against a German-Flemish alliance led by Emperor Otto IV on July 27, 1214, in Northern France. Upon the coalition’s surprise loss, the Capetian will be able to expand the royal realm and cement his dominance against his European competitors. This was an early instance, alongside the Battle of Hastings, in which a ruler “tempted God,” or dared to risk being smeared with blood and losing his life on the battlefield. The victory at Bouvines is significant because it would have sparked a newfound “national feeling” throughout France.

On July 27, 1214, in Northern France, King Philip Augustus of France led his army against a German-Flemish alliance led by Emperor Otto IV. This engagement, known as the Battle of Bouvines, is considered to be the first major conflict between the two countries. Capetian will expand the royal territory and strengthen his authority against his European competitors once the alliance is unexpectedly defeated. It was one of the first battles, like the Battle of Hastings, in which a ruler “tempted God,” or took the chance of getting covered in blood and dying in battle Bouvines is particularly significant since a “national sense” in France would have emerged after this triumph.

Background of the Battle of Bouvines

Philip Augustus had continued his war against the Plantagenets (Richard the Lionheart and John Lackland) even after returning from the Crusades, eventually conquering Normandy in 1204. Similarly to the monarch of England, the French king took an interest in the civil wars that were ripping the Empire apart, and he picked sides according to his interests, as he had done from the very beginning of his reign.

The scenario appeared excellent until the issues involving King John of England and Pope Innocent III were added. The pope had outlawed England in 1206 and excommunicated the son of Henry II in 1209. Philip Augustus, saw an opportunity and instructed his son Louis to plan an invasion of England. The attempt failed, and in 1213 John Lackland formed a coalition against his French adversary, gaining the backing of the Count of Boulogne, Ferrand of Portugal (who became Count of Flanders), and most importantly Otto IV, whose rival Frederick Hohenstaufen was backed by the Capetian.

By 1213, Philip Augustus had made up his mind to launch the attack in Flanders. If the English had opted to establish a new front by landing at La Rochelle, his son Louis (the future Louis VIII) would have exacted his vengeance. At La Roche-aux-Moines, the French triumphed (July 2, 1214). For the King of France, the situation in the North was increasingly precarious as the coalition troops were reunified and Otto IV invaded Flanders.

The forces at work

The showdown ended the conflict in more ways than one. Two major monarchs attending at once is a notable anomaly for the time period. The validity of the war is at stake, and that legitimacy is bestowed by the outcome, which is clearly determined by God.

Philip Augustus was not one to make serious promises. Several of his famous knights and vassals were standing around him. These were Duke Eudes of Burgundy, Guillaume des Barres, Gautier de Nemours, and the Count of Sancerre. Brother Guerin, a member of the Hospitaller order, also helped the monarch. About 7,000 men served in the royal army, including 1,300 knights and the same number of mounted sergeants; the infantry was made up of municipal militias with a checkered history. Symbolizing the Holy Trinity, the entire thing is structured around the flag of Saint Denis. The battlefield was meticulously demarcated, and the bridge at Bouvines was shut to prevent the French soldiers from escaping across the marshes.

The alliance lined up 1,500 knights, the same number of mounted sergeants, and somewhat more infantry made up of Flemish militias and English mercenaries to face the royal ost. Attendees included Renaud de Dammartin, Count of Boulogne, Hugues de Boves, the Count of Salisbury, the Duke of Brabant, and the Count of Flanders Ferrand, in addition to Otto IV.

Battle of Bouvines (July 27, 1214)

The conflict was ignited by Brother Guerin and the French right wing. It charged the Flemish knights and their count, breaking through their lines after many charges; it was made up of Burgundians and Champenois. “A capture! It’s Ferrand!” The middle is less resolved; it is there, around Philip Augustus and Otto IV of Brunswick, that the most significant soldiers are at odds. The infantry can’t absorb the cavalry’s shock, and thus the battle devolves into a chaotic maelstrom. The French monarch is disarmed but is rescued by intervening knights, while the emperor is forced to escape.

On the left, Robert de Dreux and Renaud de Dammartin were battling, thus their adversaries were familiar with one another. The latter put up a fierce fight, and it was only until Brother Guerin arrived to provide reinforcements that they finally capitulated. The duke of Brabant and Otton IV himself, among the gathered leaders, escaped as the royal army began its chase. Philip II, now often referred to as “Augustus” because of his unchallenged triumph, declared an end to the battle.

Aftermath and legacy of Bouvines

The English monarchical crisis develops as John Lackland goes missing; Otto IV is significantly weakened in his war against the Hohenstaufen, the future Frederick II; and the major feudal lords (for example, in Flanders) are forced to submit to the Capetian monarchy. The latter declares its status as the world’s preeminent force and validates its territorial gains of recent years.

The domestic ramifications, however, are of far greater significance to the French monarchy. The benefit that Philippe Auguste might get from this triumph was apparent almost immediately; large celebrations were held, and the captives were paraded about. William the Breton, for example, wrote the Philippide, a 10,000-verse ode to Philip Augustus and the Capetian monarchy, between 1214 and 1224. Following this triumph, the latter sought to establish a sense of “national spirit” (an outdated word, but one that conveys the pivotal nature of the war) around himself and the victory.

In spite of the monarch and his propagandists, it is important to place Bouvines in its proper historical context during the reign of Philip Augustus. It seems to have stayed within the Loire region and was mostly unknown across the Empire. Consequently, there was not much “national resonance” at the time.

Bouvines’s legacy was cemented in the 19th century, when historians, inspired to produce a “national romance,” designated the year as a key moment in the establishment of the French state. So, Ernest Lavisse put it in writing: “Thanks to Bouvines, our nation, safe in its birthplace, now presents a stunning image to the rest of the globe. This majesty was the fitting coronation for the genuine France, the one whose tale will unfold unbroken long after we are gone.” Keeping Bouvines in the national consciousness is thus essential.

Bibliography:

- Jean-Louis Pelon et Alain Streck, Bouvines 2014 : Une bataille aux portes de Lille, Hazebrouck, La Voix, coll. « Secrets du Nord », 2014, 68 p. (ISBN 978-2-84393170-3), p. 39.

- Bouvines : pour Louis de Bourbon, « la conscience politique du peuple français est née dans cette plaine » » [archive], La Voix du Nord, 28 juillet 2014

- Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). Battles that Changed History: An Encyclopedia of World Conflict. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598844290.

- Grant, R. G. (2017). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. Chartwell Books. ISBN 978-0785835530.