The Battle of Camarón (Mexico, 1863) is a foundational episode for the French Foreign Legion, which celebrates this “French version of the Alamo” every year. In 1862, France came to the aid of Emperor Maximilian, whom they had installed on the Mexican throne. On April 30, 1863, a detachment of about sixty legionnaires distinguished themselves at Camarón by standing their ground against 2,000 Mexicans. This minor historical event, within the context of the Mexican expedition launched by Napoleon III, has been elevated by the Legion to become a cornerstone of its tradition.

Context of the Battle of Camarón

Since its independence, Mexico had been a weakened country both territorially (having ceded California, Utah, Nevada, Colorado, New Mexico, and part of Wyoming to the United States), politically (with strong divisions between conservatives and liberals), and especially economically. In 1858, under the presidency of the anticlerical Benito Juarez, a rebellion led by conservative generals shook the country.

By 1861, President Juarez had finally pushed back the rebels, but the conflict delivered a fatal blow to Mexico’s economy. Despite the nationalization of church assets, the country found itself unable to repay its European creditors. Juarez decided to suspend debt payments for two years to Spain (9 million pesos), France (3 million), and especially the United Kingdom (70 million).

For Napoleon III, the French emperor, this was an opportunity. A military intervention could replace the weak republic, which was embroiled in civil war and defaulting on its debts, with a Catholic empire allied with France. This was a good way for France to extend its informal empire and its “soft power” over the New World. The opportunity was even more favorable since the United States, embroiled in its own civil war, was in no position to intervene with its Mexican neighbor.

However, the Mexican expedition was not to appear as a purely French imperialist initiative. Everything was decided in collaboration with other powers affected by Mexico’s debt: Spain and the United Kingdom. Thus, on October 31, 1861, the London Convention took place, providing the framework for a military expedition in the name of debt repayment and the protection of European nationals. The official and shared goal of the intervention was to pressure the Mexican government by seizing ports on the east coast.

But for Napoleon III, the idea was to offer the Mexican crown to Archduke Maximilian, brother of the Austrian emperor, which would also strengthen ties between France and Austria in Europe. Mexican émigrés had convinced him that the people were tired of civil wars and awaited a monarchical restoration, promising to rise as one to fight alongside the French.

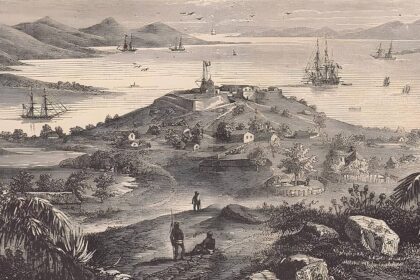

International Operation Against Mexico

Thus, a coalition intervened against the Mexican republic: the Spanish, who were already in Cuba, sent General Joan Prim with 6,300 men against their former colony. The British contributed their key asset, the navy, under Admiral Dunlop. France deployed the largest contingent. On December 17, 1861, the Spanish landed, followed by the French under Admiral Jurien de La Gravière on January 8, 1862. The French expected a jubilant crowd in Veracruz, eager for the return of the monarchy, which would provide many local recruits. However, that was not the case. They only rallied the modest, ragtag group of General Galvez (about 200 men).

Worse, the sanitary conditions quickly deteriorated in this region, known as the “Hot Lands,” where yellow fever and black vomit (vomito negro) were rampant. Facing this precarious situation and the Mexican republic’s desire to find a peaceful solution to the conflict, a convention was signed at La Soledad. This agreement allowed the allies to advance further inland, where the fever was less severe, while they negotiated a debt settlement. The allies signed the convention, although Jurien de La Gravière disliked this implicit recognition of the Mexican government.

Anxious to leave this inhospitable region, the Spanish and British quickly concluded a new financial agreement (which would be no more respected than the previous ones) and withdrew their troops.

However, the French side saw a different outcome. Jurien de La Gravière was dismissed, General Latrille de Lorencez took command of the troops, and France embarked alone on a phase of conquest. Citing the mistreatment of French residents in Mexico, the French Empire declared war on a “wicked government that had committed unprecedented outrages.”

Beginning of the Mexican Expedition: The Siege of Puebla

The French expeditionary corps, numbering fewer than 7,000 men, with 10 cannons (small 4-pounder pieces), few supplies, and no reserves, was about to embark on a hazardous conquest of Mexico. On April 27, Lorencez marched on Puebla de Los Angeles, a city portrayed to him as loyal to monarchists and ready to open its gates. However, on May 4, he found himself facing a fortified city defended by 12,000 Mexicans. Outnumbered and receiving little support from the hoped-for popular uprising, Lorencez attempted an assault, which ended in failure.

Fully aware of his lack of military resources to carry out any conquest, Lorencez retreated (in what is called the Retreat of the Six Thousand) to Orizaba, where he dug in, awaiting reinforcements from France. Lorencez’s reports detailed the absence of any monarchist faction supporting France. As if this defection wasn’t enough, Maximilian himself seemed hardly invested in the future of his hypothetical kingdom. However, for Napoleon III, withdrawal so soon after a failure was not an option, so he sent reinforcements: around 23,000 men landed during the summer under General Élie-Frédéric Forey, who reestablished contact with Lorencez, now dismissed from his duties.

For Napoleon III, the situation had become increasingly complex. His plan now seemed to be to overthrow Juarez’s republic and establish a stable government while awaiting a popular consultation to determine the country’s future political direction (which was barely feasible in a country without an administrative structure). Whether this ended with an Austrian or a Mexican in power mattered little to France as long as they remained a loyal ally in the future.

For the moment, it was necessary to conquer the territory, and for that, Forey took the time to equip his forces, purchase mules and horses (from Cuba and the United States), and familiarize himself with the new theater of operations: a hostile country both geographically (lack of roads) and in terms of its inhabitants (the development of guerrilla warfare). Between him and Mexico stood General Ortega and the Mexican army, as well as the city of Puebla. Forey decided to organize a formal siege around Puebla, where he arrived on March 12, 1863. After heavy artillery preparation, Fort San-Javier was taken on March 28, marking the start of a long street battle that would only end in mid-May with a French victory.

Battle of Camarón

During the siege of Puebla, the communication line with Veracruz was crucial. Supplies and ammunition arrived through this route, making it a vital axis for the French army. Naturally, it became a prime target for Mexican guerrillas, who constantly harassed French troops in the area. To secure the zone, the French deployed 400 men from the Egyptian Negro Battalion (provided by the Viceroy of Egypt), counter-guerrilla troops under General Dupin, and four battalions of the Foreign Regiment.

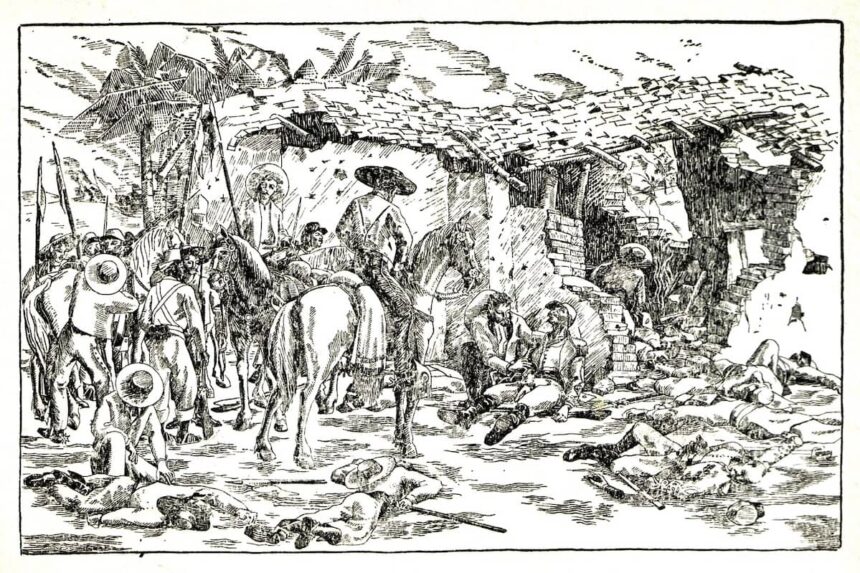

It was in this context that the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of this regiment was annihilated in the village of Camarón (later known as Camerone) after a heroic resistance. The details of the combat at the hacienda are only known through reports from survivors. From these testimonies, the official and epic account of the battle was written and read to legionnaires every April 30th:

“The French army was besieging Puebla. The Legion’s mission was to ensure the movement and safety of convoys over 120 kilometers. Colonel Jeanningros, the commander, learned on April 29, 1863, that a large convoy carrying three million in cash, siege equipment, and ammunition was en route to Puebla. Captain Danjou, his adjutant-major, decided to send a company to meet the convoy.

The 3rd Company of the Foreign Regiment was selected, but no officers were available. Captain Danjou took command himself, and Sub-lieutenants Maudet, the standard-bearer, and Vilain, the paymaster, volunteered to join him.

At 1 a.m. on April 30, the 3rd Company, consisting of three officers and 62 men, set out. They had traveled about 20 kilometers when, at 7 a.m., they stopped at Palo Verde to make coffee. At that moment, the enemy revealed itself, and the battle immediately began. Captain Danjou formed a square formation, and while retreating, successfully repelled several cavalry charges, inflicting significant losses on the enemy.

Upon reaching the inn at Camarón, a large building with a courtyard surrounded by a three-meter-high wall, he decided to fortify there to hold off the enemy and delay their ability to attack the convoy for as long as possible.

While the men hastily organized the defense of the inn, a Mexican officer, highlighting their overwhelming numbers, demanded Captain Danjou’s surrender. He responded, ‘We have ammunition, and we will not surrender.’ Then, raising his hand, he swore to defend to the death and made his men take the same oath. It was 10 a.m. For eight hours, these 60 men, without food or water since the previous day, resisted 2,000 Mexicans: 800 cavalry and 1,200 infantry, in extreme heat, hunger, and thirst.

At noon, Captain Danjou was shot in the chest and killed. At 2 p.m., Sub-lieutenant Vilain was struck in the forehead and fell. At that point, the Mexican colonel succeeded in setting the inn on fire.

Despite the heat and smoke that increased their suffering, the legionnaires held their ground, though many were wounded. By 5 p.m., only 12 men capable of fighting remained around Sub-lieutenant Maudet. At that moment, the Mexican colonel gathered his troops and told them how shameful it would be if they failed to defeat this small group of brave men (a legionnaire who understood Spanish translated his words as they were spoken). The Mexicans were preparing for a general assault through the breaches they had opened, but before attacking, Colonel Milan once again summoned Maudet to surrender; Maudet scornfully refused.

The final assault began. Soon, only five men remained with Maudet: Corporal Maine, and legionnaires Catteau, Wensel, Constantin, and Leonhard. Each still had one cartridge left; they fixed bayonets and, taking refuge in a corner of the courtyard with their backs to the wall, prepared for a final stand. At a signal, they fired point-blank at the enemy and charged with bayonets. Maudet and two legionnaires fell, mortally wounded. Maine and his two comrades were about to be massacred when a Mexican officer intervened and saved them. He shouted, ‘Surrender!’

‘We will surrender if you promise to care for our wounded and allow us to keep our weapons,’ they replied, with their bayonets still threatening.

‘We refuse nothing to men like you!’ responded the officer.

Captain Danjou’s 60 men had kept their oath to the end. For 11 hours, they resisted 2,000 enemies, killing 300 and wounding as many. Through their sacrifice, they saved the convoy and completed their mission.

Emperor Napoleon III decided that the name “Camarón” would be inscribed on the Foreign Regiment’s flag, and that the names Danjou, Vilain, and Maudet would be engraved in gold letters on the walls of the Invalides in Paris.

Additionally, a monument was erected in 1892 at the site of the battle. It bears the inscription:

‘Here, fewer than sixty men

Faced an entire army.

Its mass crushed them.

Life rather than courage

Abandoned these French soldiers

On April 30, 1863.

To their memory, the nation erected this monument.’Since then, when Mexican troops pass by the monument, they present arms.”

However, the official account says nothing of the events that allowed the survivors to tell their story. In fact, Captain Saussier’s company, which arrived at the scene the next day, found only the drummer Laï, who had been left for dead with nine bullet and lance wounds. General Dupin’s counter-guerrilla troops attacked the village of Cueva Pentada on June 13 and liberated one of Camarón’s survivors, Legionnaire de Vries.

On June 28, they took the village of Huatusco, defended by guerrillas who had participated in Camarón, and discovered Sub-lieutenant Maudet’s grave, which two Mexican officers had entrusted to their sister’s care in vain. Finally, on July 14, 1863, twelve surviving prisoners were exchanged for Mexican Colonel Alba. Thus, 14 legionnaires survived the battle. Most of them were promoted and decorated.”

Camarón: the Founding Myth of the Foreign Legion

In the broader context of French history, and even within the scope of the Mexican expedition, the Battle of Camarón is just a small event—essentially a skirmish involving only about sixty French soldiers. Nevertheless, this “French Thermopylae” has been completely mythologized and glorified, to the point that it overshadows the collective memory of the expedition’s ultimate failure in Mexico. So why this fascination with Camarón? Every military corps needs its traditions, its “founding myths” of sorts, with memorable events where past heroes are held up as examples. The Foreign Legion, which was still quite new at the time (founded in 1831), needed its own.

A few months after the event, Colonel Jeanningros obtained permission from the emperor to have the name “Camarón” embroidered on his regiment’s flag (a practice now extended to all Legion flags). Napoleon III also had the names “Camarón, Danjou, Maudet, Vilain” inscribed on the walls of Les Invalides. On May 3, 1863, Colonel Jeanningros erected a wooden cross at the battle site, inscribed with “Here lies the 3rd Company of the 1st Battalion of the Foreign Legion.” This cross was later replaced with a stone column. In 1892, the French consul Edouard Sempé raised a monument through public subscription, which was rebuilt and inaugurated in 1965.

Camarón is, therefore, a real historical event in which a small group of legionnaires distinguished themselves. However, through commemoration, the event has been essentialized to embody a certain spirit. What is called the “spirit of Camarón,” which is meant to inspire every legionnaire, is the ability to obey and fight to the death (since almost the entire force was wiped out) for the success of the mission (the Mexicans were delayed, and the convoy was saved). In other words, it symbolizes true self-sacrifice and a sacred sense of duty.

The sacred aspect is not an exaggeration, especially considering that Camarón includes what could be seen as a relic: Captain Danjou’s wooden hand. This prosthesis was searched for in vain by the relief column and was allegedly taken by a Mexican guerrilla before ending up in the hands of a French ranch owner near Tesuitlan, where Austrian lieutenant Karl Grübert reportedly purchased it.

According to other sources, it was found during the arrest of General Ramirez. Colonel Guilhem deposited it at Sidi Bel Abbes (the Legion’s headquarters) in 1865. Today, it is housed in the crypt of the Legion’s Museum of Remembrance in Aubagne and is only brought out for commemorations of the battle. Danjou’s hand has all the characteristics of a religious relic: a debated origin, sanctification in a significant place, and regular exhibition for an important celebration.

Since 1906, the official account presented above has been read to legionnaires every April 30th, so that the example of these sixty men from the Second Empire becomes a model. The phrase “faire Camarón” has spread beyond Legion ranks and into society, becoming synonymous with “fighting to the ultimate sacrifice.

“