In the second Punic War (Punic Wars), on August 2, 216 BC, a Roman army and Hannibal’s army fought a bloody battle near the city of Cannae (Apulia) called the Battle of Cannes. In the summer of 216 BC, after crossing the Alps, the Carthaginian general’s troops set up camp on the banks of the Aufidus River near Cannes. The Roman army led by consuls Lucius Aemilius Paullus and Gaius Terentius Varro tried to destroy them, but the Carthaginians won the battle, which was very bloody. Even though the Roman army was bigger, this battle was a terrible loss for them. It also put the Carthaginian general Hannibal on the map as one of the best military strategists. His strategies are still taught in some military schools.

Towards the four-way pass

Hannibal took up arms in 218 BC. He crossed Spain and southern Gaul, then the Alps, and poured his armies into Italy. He surprised the Romans in the Po Valley, won the battles of Ticino and Trebia, and then joined the Celts, who had just been defeated by the Romans. In 217 BC, he did it again without waiting for the winter to end. He caught his opponents by surprise. At the Battle of the Trasimene Lake, he beat the Roman army by taking advantage of the terrain and weather.

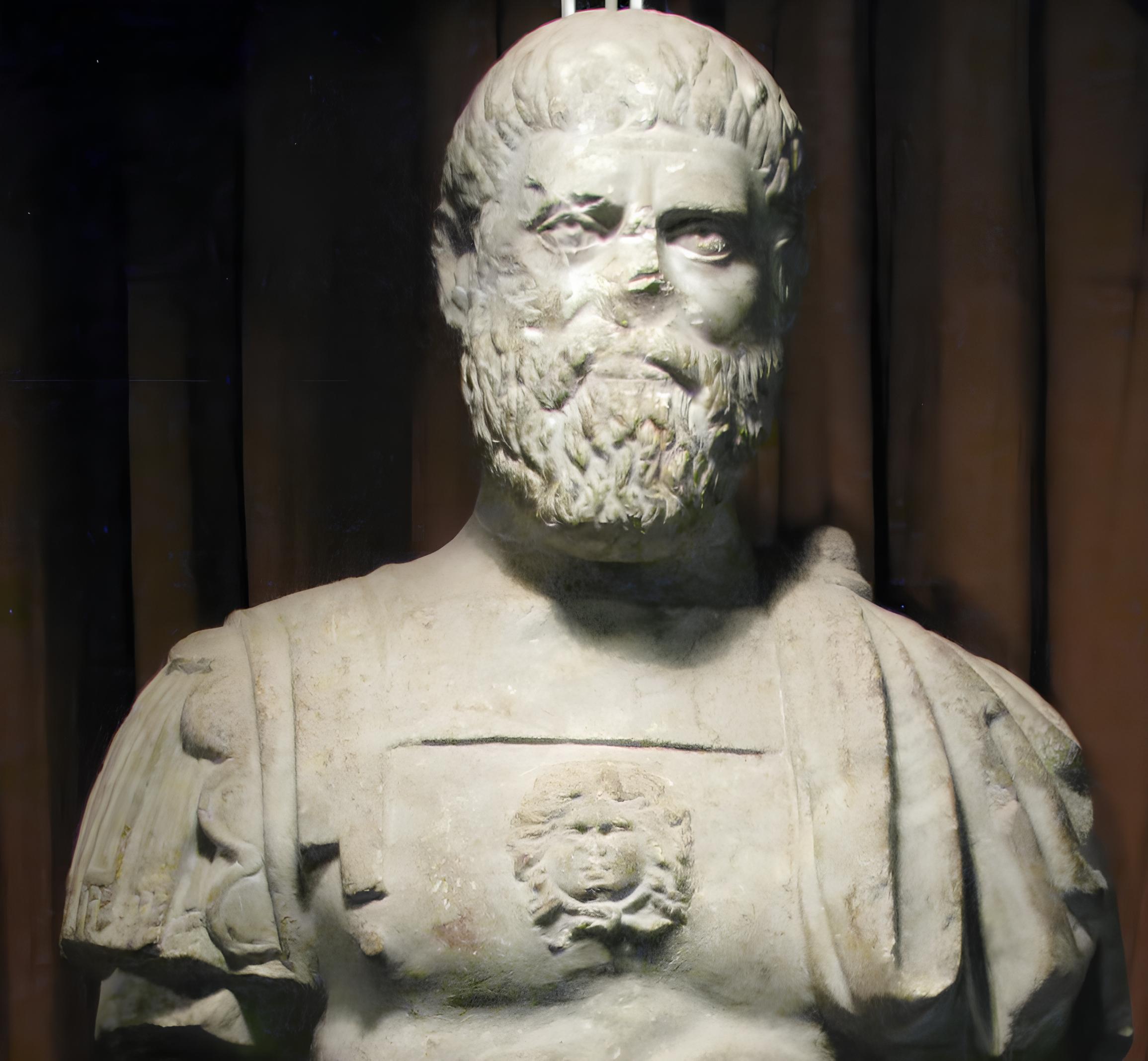

Rome paid a very high price for these three fights. More than 30,000 people died, and Rome’s reputation with its allies was hurt. Hannibal, on the other hand, tried to show himself as the new Alexander. He was a great tactician in the military, and he also played on the political chessboard, promising to bring “freedom” to the Italian cities that were under the control of the Romans. After that, Rome used a strategy called “temporization,” which meant avoiding frontal attacks and constantly harassing the Punic army in an “attrition war.” Still, it decided to stop Hannibal from doing what he was doing, which was destroying Apulia, Samnium, and Campania.

In 216 BC, Lucius Aemilius Paullus, also known as Paulus, and Gaius Terentius Varro, also known as Varro, became the new consuls. Paulus liked to harass and wear out the African troops, while Caius Terentius Varro, also known as Varro, wanted direct confrontation. Meanwhile, the common people were getting tired of the fighting. Polybius, a Greek historian, said that the Punic troops were facing off against no less than eight legions, which was “a number that had never been reached before.” Together with its allies in Italy, the Roman army had close to 80,000 men. On his side, Hannibal’s army of about 50,000 men was still raiding in southern Italy. They raided the warehouses of corn for the Roman army in a small city in Apulia called Cannes, which was now called Canne della Battaglia.

Battle of Cannes: Hannibal reaching the top

On August 2, 216 BC, the two armies would have their most important meeting. The Roman army was then led by Varro, who made each consul take charge of one day every two. He also made each soldier take on the most traditional form. Paulus was in charge of the right wing, while the allies’ cavalry took care of the left. At the level of the infantry in the center, there was nothing new in terms of strategy. The hard core was formed by the Roman legions, which were known to be the best trained, and the wings were formed by the allied legions later.

Hannibal came up with the most daring plan which was characterized by its will to fight a battle of encirclement and annihilation. In the middle, facing the Roman legions, he put the Gallic infantry. On either side, he put its best troops, the African heavy infantry, which he commands himself. The cavalry was on the wings. Hasdrubal Barca was in charge of the Iberians and Gauls on the left, and Hanno was in charge of the Numidians on the right.

The Carthaginian general’s plan was to move his center (the Gallic infantry) forward. The Romans, however, rushed to the attack and quickly pushed the Gallic infantry back. The cavalry fights on the wings, quickly turning in favor of the Punic. Hasdrubal wiped out the Roman cavalrymen and came to help Hannon by pushing the Italian allies’ cavalry back. He then went backwards. It was then too late for the Roman infantry, which could see that the enemy was getting closer and closer while it thought victory was close. In fact, if the Gauls in the middle moved back, they didn’t give up. This let the heavy Punic infantry gradually surround them on the left and right by conversion, while the horsemen, freed from their Italian opposite, stopped any possible retreat and completely closed the trap. The trap worked perfectly, and the rest of the battle of Cannes was just a massacre.

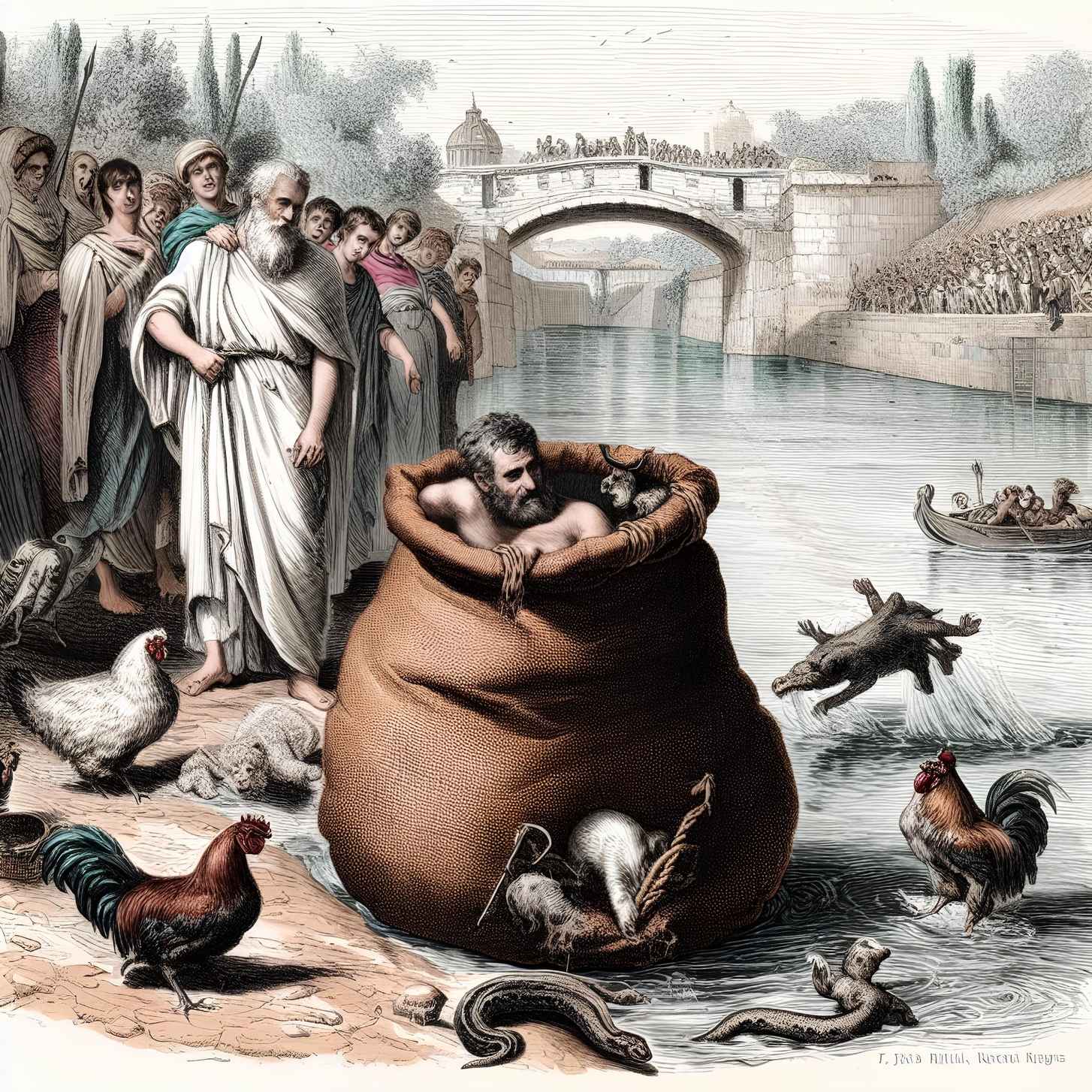

Battle of Cannes: The Roman army’s mortuary field

One of Rome’s biggest armies was wiped out in combat. Despite discrepancies in survivor counts, it was widely accepted that 45,000 Roman troops were killed and 20,000 were captured. Only around 15,000 males managed to escape. The bleeding was so bad that even Roman senators and high-ranking magistrates were afflicted. Military tribunes, former consuls, bankers, and quaestors were among the dead, as was Lucius Aemilius Paullus. Varro escaped with a young soldier called Scipio, who at the time was not recognized as African but who would soon surpass the master since he was an excellent pupil. Only roughly 6,000 of Hannibal’s troops were killed, but they were mostly Gallic, an unstable and disorderly bunch.

Despite Rome’s best efforts, it seemed they were going to lose the battle with Carthage, one of their most difficult conflicts. One of Hannibal’s subordinates was said to have informed Titus Livius, “You know how to win, Hannibal, but you don’t know how to exploit your triumph.” In any case, Rome would have had to concede defeat and respond with military and political measures. You could still win the war even if you lost a battle.

Bibliography:

- Plutarch (1916). “Life of Fabius Maximus”. Loeb Classical Library.

- Polybius, The Histories, translation by W.R. Paton.

- Briscoe, John & Simon Hornblower, eds. (2020). Livy: Ab urbe condita Book XXII. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-48014-7.

- Cicéron (trad. Maurice Testard), Les Devoirs, Les Belles Lettres, 1965.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2001). Cannae. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35714-6.

- Yann Le Bohec, Histoire militaire des guerres puniques, Éditions du Rocher, 1996.