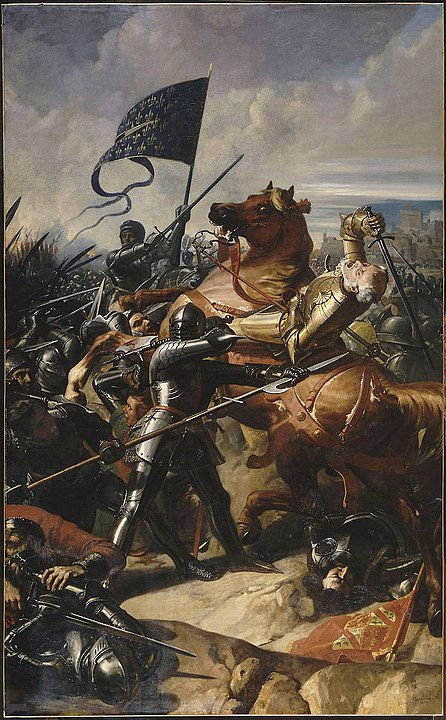

The Battle of Castillon, fought on July 17, 1453, marked the conclusion of the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453) and, more generally, the end of the Middle Ages. Specifically, this victory represented the complete independence of Guyenne (Aquitaine) in southern France from the English for the first time in three centuries. This was King Charles VII‘s fourth military triumph, after the Joan of Arc narrative, the 1429 Battle of Patay in the Pays de la Loire, and the 1450 conquest of Normandy in the Seine Valley.

In fact, the Valois dynasty (a branch of the Capets) and the Plantagenets fought continuously from 1337 to 1453, and through them, the kingdoms of France and England fought for control of emblematic fiefdoms like Guyenne (now Gironde, Dordogne, Lot-et-Garonne, Lot, and Aveyron). This period is commonly referred to as the Hundred Years’ War.

The Battle of Castillon was highly significant because it marked the end of the Hundred Years’ War. It resulted in a decisive French victory and the withdrawal of English forces from France, effectively ending English territorial claims in mainland France.

Causes of the Battle of Castillon

In 1420, the kingdom of France was on its last legs. By the Treaty of Troyes (1420), King Charles VI had deprived his son Charles of the throne in favor of the English monarch. The first reconquests under Joan of Arc intensified following the coronation of Charles VII as the new King of France in Reims (1429), whetting the Valois appetite once more. Some important castles were recaptured: Orléans, Paris, Champagne, and Normandy.

What remained was Charles VII’s obsession with Guyenne, then largely under English influence, and in particular with the flourishing wine trade.

How Was the Battle of Castillon in 1453?

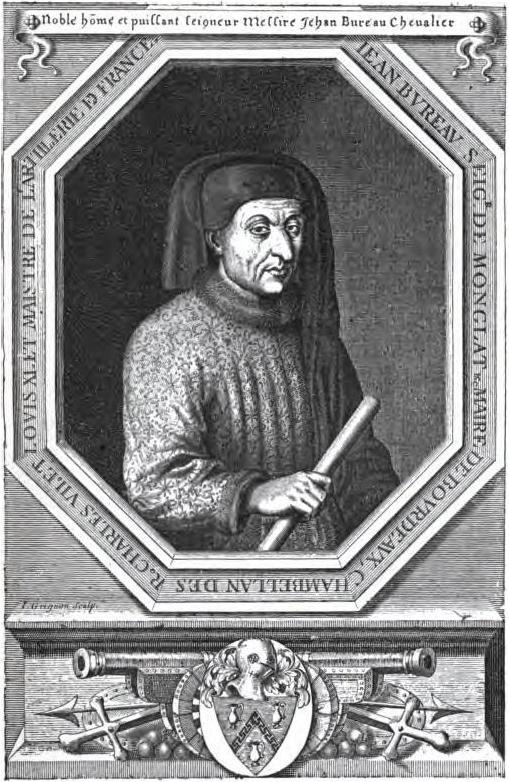

By the spring of 1453, negotiations had broken down and conflict in Guyenne was inevitable. King Henry VI appealed to the pro-English Bordeaux and sent 3,000 men under the charismatic army commander John Talbot to reinforce a few thousand soldiers from Guyenne and Gascony. Charles VII sent his best military leaders, notably Dunois and Bureau, to lead 9,000 men, both French and Bretons. Historians explain Castillon’s victory by two closely related factors:

The French forces were led by Jean Bureau and the British by John Talbot, 1st Earl of Shrewsbury.

The French set a trap and established their camp above Bordeaux, east of the small village of Castillon, where the British were trapped, besieged, and massacred. This battle also marked a break in military methods; the cavalry’s decline against the infantry and artillery gave the French the upper hand. The French victory was thus complete. Bordeaux was taken in October. Charles VII pardoned the Bordeaux rebels and the English left Guyenne on October 19, 1453.

The French victory at Castillon was attributed to several factors, including the effective use of artillery by the French, the strategic leadership of Jean Bureau, and the decline of English military resources and support.

On the French side, the battle left around a hundred men dead or wounded. The English lost 4,000 men, of whom 500 to 600 were killed (2,000 or more according to the Chronique du temps de Charles VII in the Sainte-Geneviève Library in Paris), the others being wounded or taken prisoner during the battle. Among the dead were Talbot, two of his sons and Baron de L’Isle, son of John Talbot, who had landed in Guyenne at the head of 2,000 reinforcements.

Occurring just a few weeks after the Turks took Constantinople, the battle of Castillon went almost unnoticed by contemporaries.

How the Battle of Castillon Ended the Hundred Years’ War

The war came to an end in 1453 when the French recaptured the city of Bordeaux, the last major English stronghold in France. This victory marked the end of English territorial claims in France and established France as the dominant power.

With the exception of Calais, which was not recaptured until five years later, the retaking of Guyenne, one of France’s most emblematic fiefdoms, nicely completed the reconquest that had begun some twenty-five years earlier with the epic story of Joan of Arc. Although this time the English were definitively “expelled from France”, the end of the Hundred Years’ War was not signed until the Treaty of Picquigny in 1475. This long and incessant period of conflict had exhausted the kingdom of France and hindered its development.

References

- Cutler, S.H (1981). The Law of Treason and Treason Trials in Later Medieval France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23968-0.

- Eggenberger, David (1985). An Encyclopedia of Battles. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24913-1. Retrieved 7 July 2022.