The Battle of Gettysburg stands out as one of the most significant events of the American Civil War. Northerners and Southerners engaged in a ferocious battle from July 1 to 3, 1863. There were only about 2,400 people living in Gettysburg at the time of the Civil War. This area was in Pennsylvania, roughly 85 miles (140 kilometers) north of Washington.

Background of the Battle of Gettysburg

The divide between the northern and southern states of the United States had grown wider over the course of many decades. The North had long since adopted a capitalist and industrial economic model far ahead of the rest of the world. The more populous and advanced it was, the more it wanted to impose its economic model and political values, especially on the issue of slavery abolition. On the other hand, a strong conservatism pervaded the South.

Its entire economy, based mostly on tobacco and cotton, was threatened by abolition, and thus it took a stand against it. Tensions were rising, and a battle seemed imminent. At the end of 1860, Abraham Lincoln was elected President. This was the spark that set the world on fire. The abolition of slavery was an issue close to Lincoln’s heart. Seven southern states left the Federal Union after he was elected. After the April 1861 attack on Fort Sumter by Southern forces, four more followed. This assault is generally considered to be the starting point of the American Civil War.

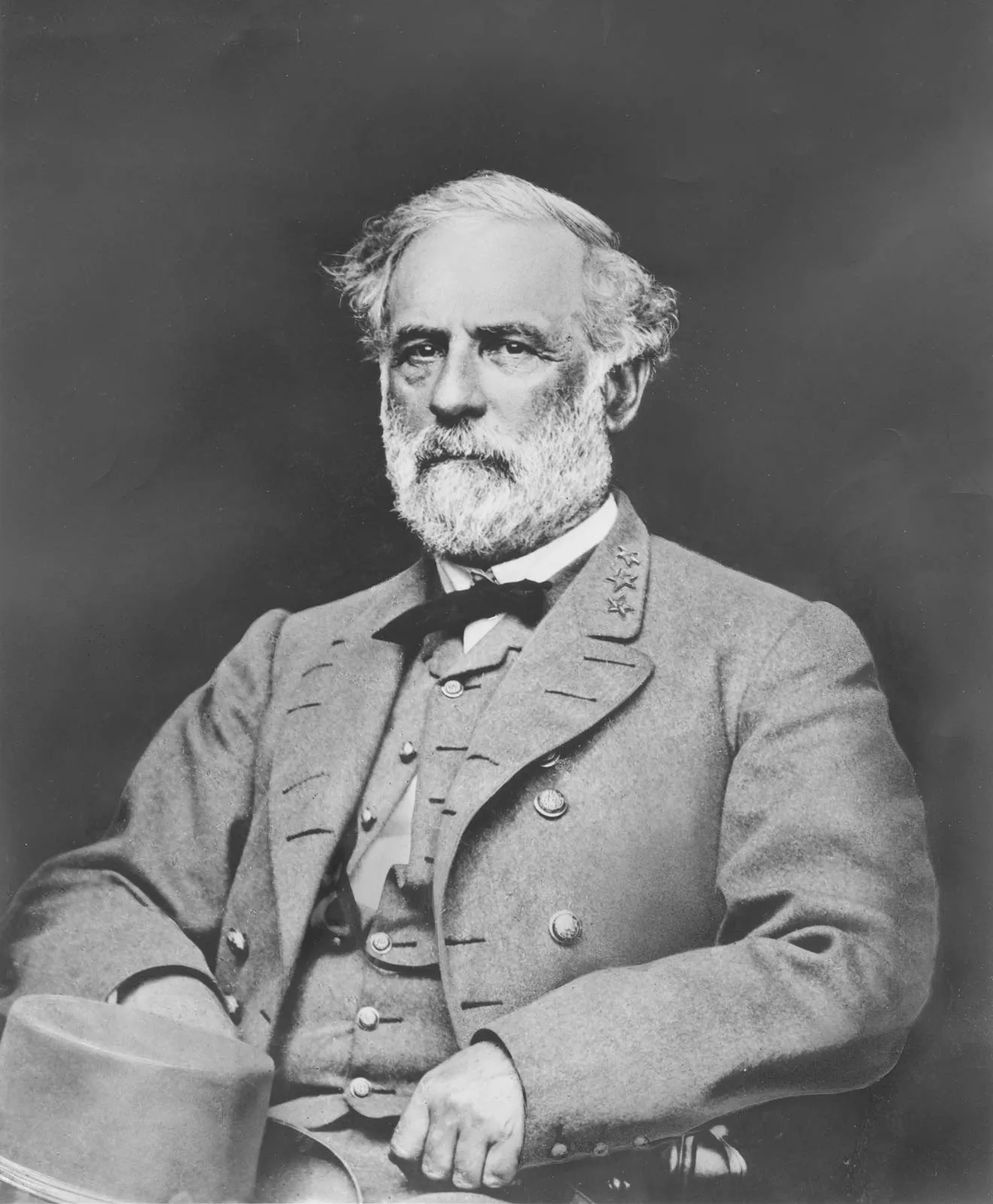

Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy’s Southern states, came under attack by General McClellan’s Northern army in the spring of 1862. Robert E. Lee, a Confederate commander, was promoted to head the Army of Northern Virginia (the Seven Days Battles, the Battle of Bull Run, and the Battle of Fredericksburg etc.) He successfully drove his foe back and was then determined to press his advantage. On June 3, 1863, he crossed into Pennsylvania from the Northern Territories. It was a brave move on his part.

Washington, DC, was in direct danger from the Confederate army. The true purpose of it was to do this. Taking the capital city would effectively end the conflict. Having graduated from the esteemed West Point Military Academy, Robert E. Lee was an accomplished military leader. There were three army corps he was responsible for, and they were led by General James Longstreet, Richard S. Ewell, and Ambrose Powell Hill. 75,000 men were ready to settle the score with the Yankees once and for all.

Lee deployed a huge number of scouts and made sure to leave plenty of distance between his three corps. A game of “cops and robbers” was being played. Whoever can see the other side first without giving up its position would have a huge advantage. However, they entered an enemy stronghold in Virginia. This was too obvious to be ignored. The Union General Staff had a good idea of where to find Lee even without knowing his precise location.

During a westward march with his army on June 28, 1863, Lee was shocked to find that the Northern Army of the Potomac was only 25 miles (40 kilometers) away. To the southeast of his position, almost on his back, it was a big army. There were more than 90,000 soldiers in this army. However, it was currently disordered and dispersed. Lee could take advantage of his superior numbers if he maintained the upper hand and acted swiftly.

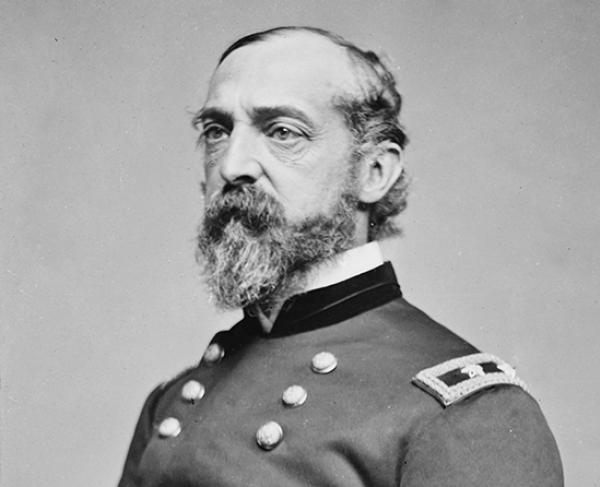

General George G. Meade led the Army of the Potomac. He had just recently assumed leadership. Several generals had declined his offer of employment. The general public had enough faith in Lee to expect a successful offensive on his part in Pennsylvania because of his reputation. The Union’s final victory against the Confederacy was a collective effort, and no one wanted to take the rap for it. Meade swiftly made up his mind to get ahead of his opponent and try to stop them before they reached Washington.

At the approach of the Northerners, Lee became anxious. Trying to maneuver when Meade was advancing could prove disastrous. Since this was the case, he made the executive decision to quickly reorganize his three corps at Cashtown, 6 miles (10 kilometers) west of a small community at the intersection of a dozen roads known as Gettysburg.

Battle of Gettysburg: The showdown

The two groups didn’t realize it, but they picked paths that eventually meet up at the same place since that was what made the most sense based on geography and military logistics. The two armies’ vanguards swiftly clashed. The first battle was fought on June 30, 1863, not far from Gettysburg. The settlement was taken over by mounted troops.

Southern brigade that did not properly identify these mounted troops kept observing them. How about a militia? Have they been identified as Potomac Army troops? Lee requested privacy while his army was being reorganized. Hill, on the other hand, reasoned that it would be appropriate to push this even further; he initiated contact by sending troops. He had a terrible temper. The horsemen he was now seeing in front of him were part of the Army of the Potomac and the Battle of Gettysburg had officially begun.

Neither of the two adversaries had planned to fight there. Lee and Meade were not even there when the first shots were fired. Each was presented with a bit of a fait accompli. Meade now needed the crossroads of Gettysburg and the roads leading to it to bring in his reinforcements and regroup his entire army. In 24 hours, the village had become a point of vital strategic importance. Lee understood this very quickly. To take Gettysburg and crush the Army of the Potomac while it was still dispersed was sure to open up the road to Washington. The Battle of Gettysburg could decide the fate of the war.

Lee had no time to lose. It was not in his temperament anyway. He had the initiative and the numerical superiority, but for how long? On the evening of June 30, he was ill. But he decided to go to Gettysburg. Before leaving, and even though his army was not completely regrouped, he gave orders for an attack to be launched the next day.

July 1, 1863

The true start of the Battle of Gettysburg occurred early in the morning. Their attack was spearheaded by two army corps from the South. When Hill’s corps moved to the west, Ewell’s corps would advance from the north, to a resounding degree. Avoiding subtlety was unnecessary. The Northern cavalry had positioned themselves strategically atop Seminary Ridge to the west of Gettysburg. They had to retreat because the shock was so powerful. However, they did it in a systematic, steady fashion. They were defeated in the village but were able to station their soldiers.

The Confederates had occupied the settlement and the surrounding heights to the west and north by the time Lee arrived in the afternoon. The Southern commander took a broad look around the battlefield. Union forces attempted to regroup south of Gettysburg. Their fortifications atop hills looked like an inverted hook, creating an almost uninterrupted line. Little Round Top and Big Round Top were the two hills that are most southern.

These two nodes made up the Northern instrument’s left side. They advanced toward Gettysburg, where their lines eventually settled on Cemetery Ridge. The battle’s core had not yet been secured. Their right, completing the hook’s bend, was supported by Cemetery Hill and the forested peak of Culp’s Hill. Then, Lee realized that Cemetery Hill could be the decisive point in the Battle of Gettysburg. Taking it would isolate the Northern core and prevent reinforcements from reaching Meade.

To get a sense of how likely it was that they could take the position before midnight, he consulted General Ewell. Culp’s Hill was directly in front of his corps’ position. Ewell, though, was not a very brave commander. As an officer, he was not particularly strategic either. In his opinion, it was currently impossible to climb Cemetery Hill. Not only that, but he made no effort to do anything at all. The tide of the Battle of Gettysburg began to change because of this holdup.

Southerners kept pouring in to help out the Northern Army. Finally, the day’s conclusion allowed the Federals to pull back and reorganize. Their defensive line stretched over 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) down the slope, from Little Round Top to Culp’s Hill. To their west, on the parallel north-south slopes of Seminary Ridge, was Hill’s corps, the core of Lee’s force. The Southern left, created by Ewell’s corps, posed a significant threat to the northeast, but the latter’s inactivity had granted them an unexpected reprieve. South of Seminary Ridge and in line with the Round Tops, Longstreet’s corps formed the Southern right.

It was becoming dark outside. Although he was still in pain, Lee stayed up late in order to plan his attack for the next day. He planned to exercise his right and advance on Meade’s position from the south. The northern general would be vulnerable after being cut off on his left. Eventually, Gettysburg would be won. Longstreet would have to launch his assault on Little and Big Round Top from the northeast. Ewell’s corps would launch a simultaneous attack on Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill to bolster this one. It was merely supposed to be a distraction.

The plan was to stop Meade from coming to help his left flank. Lee, on the other hand, hoped that, depending on how things played out, this move could blossom into a full-scale assault. Some further harassment from Hill’s corps in the center was necessary to keep Meade’s units from being detached and used to strengthen his left flank. Lee was an astute strategist. So that Meade wouldn’t be able to identify the location of the major attack until as late as possible, he requested that these several encounters take place in accordance with a well-ordered schedule.

This strategy was really bold. In the same way, Lee’s was. This, however, would have needed similarly courageous senior officers. General Jackson was Lee’s best offensive tactician, but two months before the Battle of Gettysburg, Lee lost him by accident. And General Stuart, his top tactician, was still on his way to the Gettysburg Battle.

Battle of Gettysburg: The charge of the 20th Maine

July 2, 1863

General Sickles, commander of the 3rd Northern Army Corps, ordered a push south of Cemetery Ridge on the morning of July 2. As a result of his own volition. He relocated his forces to a spot from which he hoped he could better direct his artillery’s volleys. The necessity of expanding, and so weakening, his position, however, left him vulnerable. This was a misstep that the Confederates could have capitalized on with a swift attack. Yet they were not prepared.

It was at this point that Longstreet requested permission from Lee to hold off on the offensive until he could bring in reinforcements. So far as the Southern commander was concerned, Sickles’ rash action had not been realized. In addition, Stuart’s cavalry and other critical units were still on their way to Gettysburg when the battle began. To waste time, he waited for Longstreet. It was for this reason that the Southern army spent the day doing very little while Unionist reinforcements kept pouring onto the battlefield. This was where the tide of the Battle of Gettysburg turned.

By the time Longstreet began his assault at 4 o’clock in the afternoon, Sickles had fortified his position and was no longer in jeopardy as he had been in the morning. Little Round Top Hill, located on the northern left flank, was the target of a Southern assault. There was fierce combat on Devil’s Den Hill, in the Peach Orchard, and the Wheatfield’s carefully tended crops.

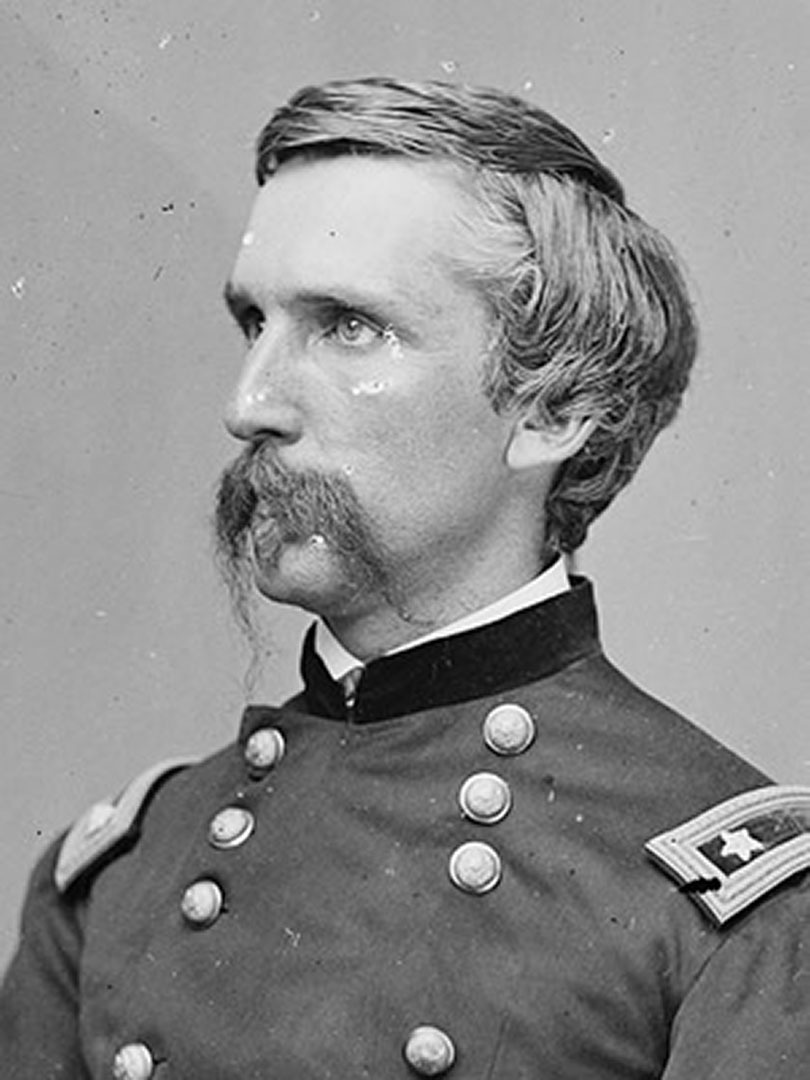

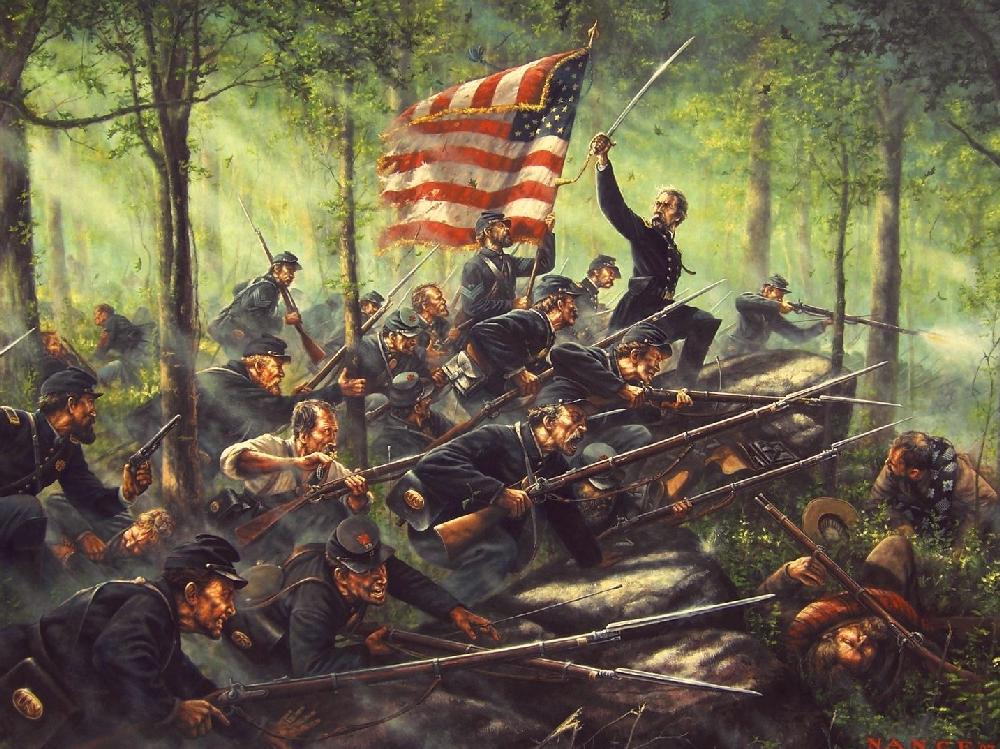

The 20th Maine Infantry Regiment, led by Colonel Chamberlain, maintained the southern slopes of the Northern position on Little Round Top. The regiment was stationed well to the Union’s left, where it was vastly outnumbered by the enemy. That job was really important. The Battle of Gettysburg would be over if it capitulated. It was so outnumbered that it resisted with great bravery. Multiple 15th Alabama Regiment attacks from the South were turned back.

They engaged in close quarters combat with anything at their disposal, including bayonets, knives, stones, rifle butts, and even their bare hands. With a ferocity and a fury of cruelty that modern people have trouble imagining. Although they were exhausted, the northerners continued to fight despite suffering massive casualties. However, after four hours of intense warfare, both sides were left without weapons.

Time was running out. It took the Confederates forever to get back together. And then the unimaginable occurred. Chamberlain opted to go all-in rather than give up. He reorganized his formation and gave the order to charge with bayonets. The 20th Maine men showed extraordinary bravery as they charged, shrieking, at the Confederate line.

Chamberlain led them, grasping the sword. Southerners were taken aback by this uprising. Like a steamroller, the charge descended the forested slope. Many prisoners were abandoned when the 15th Alabama escaped. Chamberlain managed to get away after being shot in the leg and foot. Their regiment became known as the “Gettysburg Lions” because of him. The Northern left wing was preserved by the 20th Maine Infantry Lions’ charge. Thus, it was immortalized in the annals of Gettysburg lore.

Ewell, on the other hand, delayed things. A more than hour-long artillery barrage preceded his attack on the northern right flank, which he launched at 7 o’clock. It was simply for nothing. The North battled fiercely to hold on to every inch of territory at the base of Culp’s Hill and Cemetery Hill, and all of his attacks were repulsed. They suffered devastating setbacks, yet they refused to surrender.

On the other hand, they were outnumbered by a huge margin. Meade, meanwhile, realized Lee’s strategy and sent out 20,000 soldiers to protect the rest of his left flank. Longstreet’s attack was successful, but Ewell’s, which was scheduled to happen simultaneously, came much too late. It managed to capture the initial Northern positions at the base of Cup’s Hill, but it was unable to go forward.

After nightfall, both sides called a ceasefire. Meade was scorching. The tide of the Gettysburg fight nearly shifted against him. His flanks were dangerously close to being penetrated by the Confederates. However, they were unable to breach his defenses. His defensive strategy relied on protecting his supply lines, which gave him the flexibility to swiftly deploy reinforcements. Lee saw that his opponent’s left flank was about to give way, and he acted accordingly. He resolved to devote his time and energy there once again the following day.

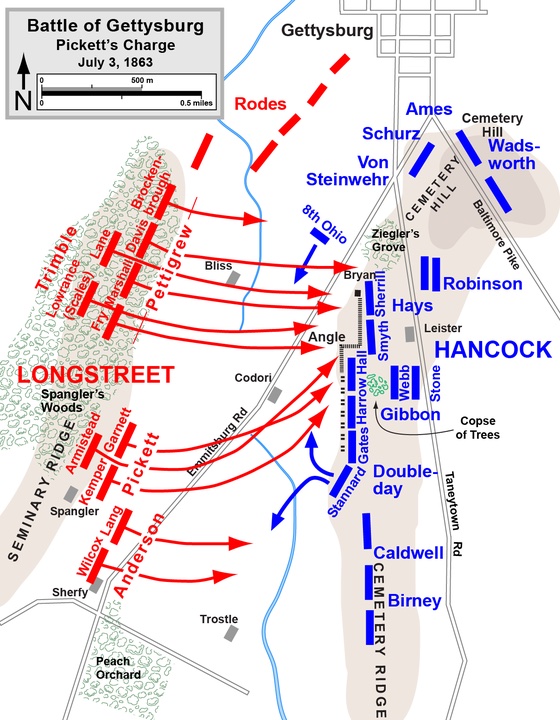

Battle of Gettysburg: Pickett’s Charge

July 3, 1863

On July 3, however, it was Northerners who were on the attack. Almost all of Meade’s reinforcements had arrived. He realized he was outgunned now. The tides of the Battle of Gettysburg shifted. Northern artillery opened a fierce morning attack on Southern forces who had captured the foot of Cup’s Hill the day before. The Union soldiers then engaged the Southern forces in fierce hand-to-hand fighting in an effort to break their grip over the South. A waste of time.

Lee decided to make a change. He planned a strike targeting the region’s geographic core in the north. General Pickett’s Division would serve in this capacity. At one in the afternoon, the Confederate artillery launched a heavy bombardment of Cemetery Ridge in an effort to break up the Northern defenses. However, General Henry Jackson Hunt oversaw the artillery units of the Union.

He knew the heavy gun setup signaled the impending arrival of a large number of infantrymen. He hung around and waited. Northerners took heavy fire from the South for around half an hour before they finally fired back. The artillery duel at Gettysburg was the bloodiest of the Civil War. The event itself took longer than two hours. Eventually, the artillerymen in the South simply ran out of bullets. Then, Hunt gave the order for them to only fire back extremely occasionally.

At about 3 o’clock, the Pickett Division began their mission. Almost 13,000 Confederate men emerged from the cover of the trees and began their charge towards Cemetery Ridge. Nearly 5,000 feet (1,500 meters) of their formidable front were taken up by their line. As they moved on, they were left in the open for more than a mile due to the steep slope they had to climb. They believed that their firepower had completely destroyed their foes. There was an error on their part. Actually, Pickett’s charge was intended to be a suicide mission. There had been a decisive shift in the Battle of Gettysburg as a result of this.

Before unleashing havoc on the South, the North waited for them to get within rifle range. Their infantry, lined up in tight formations, fired salvo after salvo. They resumed their heavy artillery fire. The strategy Hunt adopted was successful. His weapons mowed down the Southern infantrymen like tomatoes.

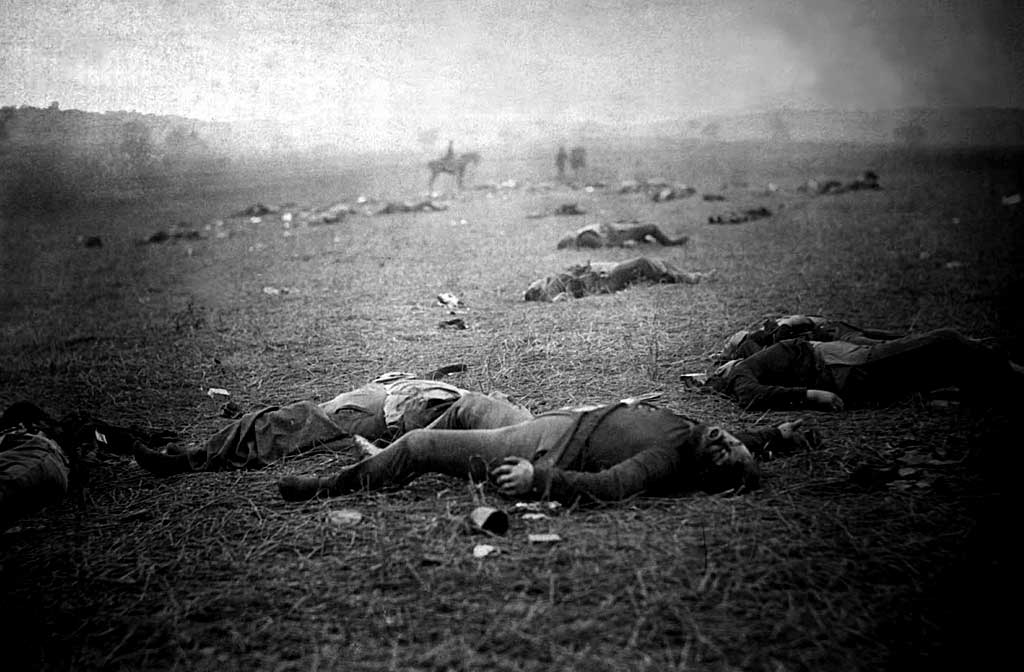

There was a downpour of iron and fire that smashed, rolled, and crushed the charge in less than an hour. It was a true slaughter. Wading down the slope through muck, guts, blood, and bodies ripped apart by cannonballs and machine gun fire was the only way out for the survivors. About 7,000 young Southerners were killed or wounded on Cemetery Ridge. It was safe to say that the Battle of Gettysburg was over.

Meanwhile, to the northeast of Gettysburg, Stuart’s Confederate cavalry was supposed to sever Meade’s rear, therefore completing Pickett’s successful attack. But after fierce swordplay, the Northern cavalry, led by one Lieutenant Colonel Custer, were able to keep it at bay.

During Gettysburg, the Confederates were defeated. Lee knew the situation was really dire. Approximately 4,500 of his troops had been killed, 17,000 were injured, and 6,500 were taken as prisoners, for a total loss of over 28,000. About a tad over a third of his total strength. The opposing side, represented by Meade, wasn’t too far ahead. He estimated that a total of 23,000 men were either dead, injured, captured, or otherwise unavailable for duty.

Nonetheless, he was still in a good position and might expect reinforcements to arrive soon. In preparation for a probable Northern counterattack, Lee hastily reorganized his defensive lines on Seminary Ridge on the evening of July 3. In actuality, this event never took place. Meade took precautions. A similar fate could have befallen Pickett’s charge-like onslaught on the slopes of Seminary Ridge. All of the fighting at Gettysburg had finally ended.

The turning point of the Civil War’s Battle of Gettysburg has been a point of heated debate among historians for decades. Without a doubt, it marked a significant inflection point. However, it was still hard to use the word “decisive.” The Union was unable to completely wipe out the Army of Northern Virginia. With President Lincoln’s aggressive orders, the Army of the Potomac followed them without conviction as it began its retreat into the South on July 4. Lee crossed the Potomac River and found safety at last.

The Battle of Gettysburg could have been the decisive fight that finally put an end to the war. It looked like the armies were still looking at another two years of the Civil War. The South, however, had been depleted by its losses since the war began and never recovered enough strength to launch another large assault on the Northern regions. The Battle of Gettysburg was a watershed moment in this regard. The South had no choice except to fight for defending territory. This would gradually weaken their army.

On November 19, 1963, five months after the Battle of Gettysburg, President Abraham Lincoln gave his famous “Gettysburg Address” on the precise ground where the battle had taken place. It was the most renowned, shortest, and poignant. Even today, the Battle of Gettysburg is known as the bloodiest conflict in American history.

Bibliography:

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. General Lee’s Army: From Victory to Collapse. New York: Free Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-684-82787-2.

- Harman, Troy D. Lee’s Real Plan at Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2003. ISBN 0-8117-0054-2.

- Wert, Jeffry D. Gettysburg: Day Three. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. ISBN 0-684-85914-9.

- White, Ronald C., Jr. The Eloquent President: A Portrait of Lincoln Through His Words. New York: Random House, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-6119-9.

- Ballard, Ted, and Billy Arthur. Gettysburg Staff Ride Briefing Book. Carlisle, PA: United States Army Center of Military History, 1999. OCLC 42908450.

- Boritt, Gabor S., ed. The Gettysburg Nobody Knows. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0-19-510223-1.

- Haskell, Frank Aretas. The Battle of Gettysburg. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1-4286-6012-0.