The Battle of Kursk, fought in western Russia from July 5 to July 13, 1943, was a defining moment of World War II. As the largest tank battle in history, it involved over 2 million men and over 3,000 Russian and German tanks. More than 100,000 Nazi soldiers died in the final large-scale offensive attempt on the Eastern Front, and Adolf Hitler suffered irreparable losses to his armored divisions, which had been unbeatable up until that point. The Soviet Union’s victory demonstrated to the world that the German Panzerwaffe was vulnerable to attack. Peaceful conditions improved to the point where the great liberating offensives of 1944 could be launched.

The context of the Battle of Kursk

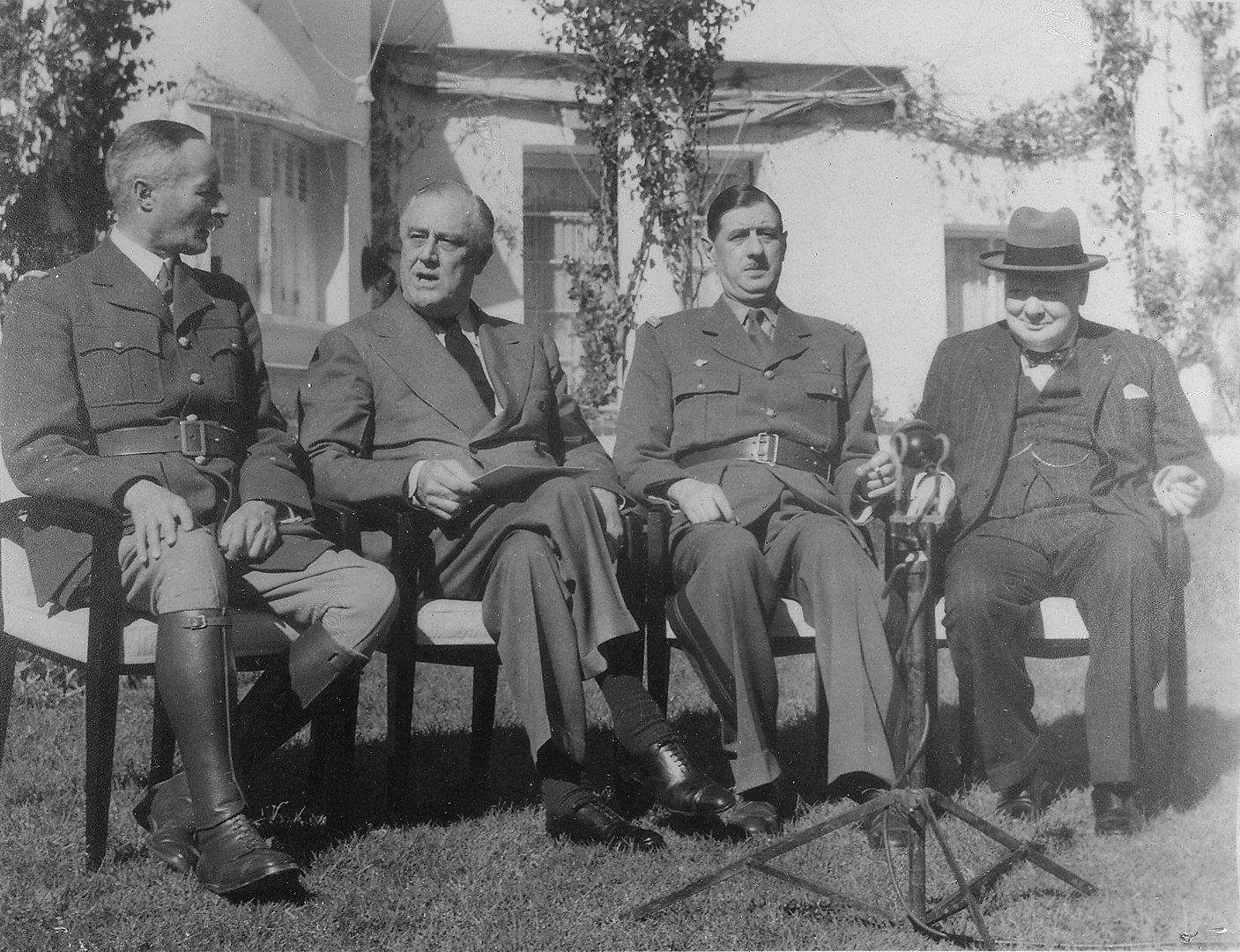

The strategic options available to the Hitler Reich in the spring of 1943 were constrained. Since the Casablanca conference in January 1943, it had been impossible to negotiate with the Western Allies. Having possibly saved his regime at Stalingrad, Stalin was in a commanding position. In terms of raw resources and manufacturing capacity, Germany was staring down the barrel of an unwinnable war of attrition. It must therefore carefully plan its next offensive move if it hopes to succeed.

Since most German resources were located in the east, it was only logical that the West German government would intervene against the Soviets. It’s crucial, first and foremost, to put to rest the horrors of Stalingrad (Battle of Stalingrad), but it’s also important to bring back Germany’s struggling allies (be it Italy, Hungary, or Romania). In addition to protecting “Fortress Europe” (Festung Europa), Hitler planned to bleed to death a Soviet Union that he believed had been weakened by two years of war with a new successful offensive in the east.

The real start-up of the war economy (the famous Totaler Krieg of Goebbels’ speech of February 1943) organized by Speer was likely to reinforce Berlin’s optimism. This allowed the Germans to reassemble their best offensive weapon: tanks. The latter was fortified and reorganized under the leadership of General Guderian (who became Inspector General of Armor), who drew inspiration from his experiences fighting Soviet armored formations (and their famous T-34). Hitler had high hopes for new equipment like the Tiger tank and the Panther tank, which could take on the most powerful Soviet armored vehicles.

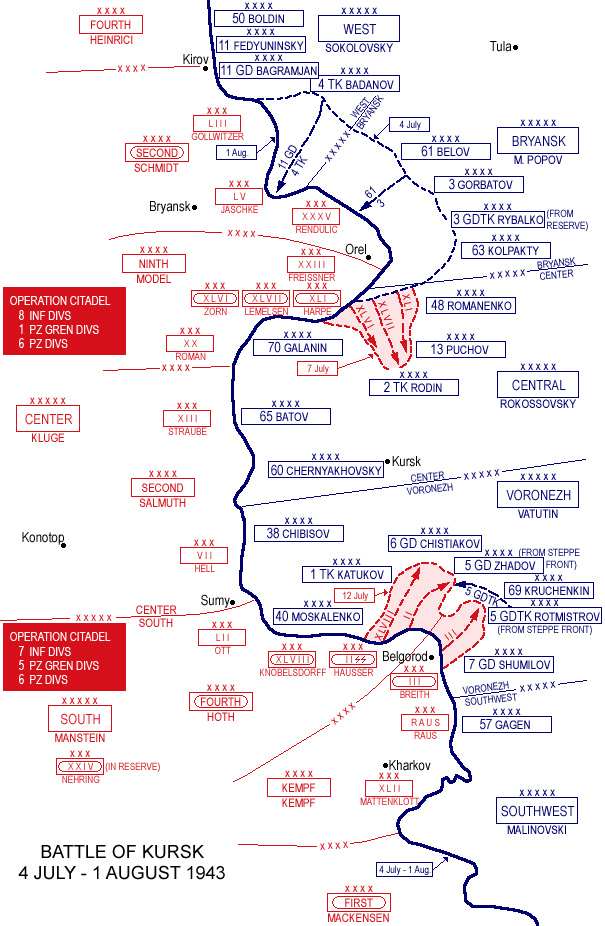

In 1943, the Allies decided to launch an offensive somewhere in the eastern hemisphere. If you look at a map of the front from that time period, you’ll see that the answer was obvious: Kursk. The winter Soviet offensives did create a salient, roughly 180 km (north to south) by 140 km (east to west). Kursk, a major railroad hub in the middle, provided the Red Army with a strong foothold from which to launch attacks south (Kharkov) or north (Moscow) (Orel).

The German high command hopes that by attacking Kursk in a preventative manner, they will be able to shorten Stalin’s front by nearly 280 kilometers, effectively depriving him of his best units (the Central Front and the Voronezh Front) (that was to say, an economy of some twenty divisions). Due to the salient’s shape, Operation Citadel will resemble a traditional pincer movement. In the south, Field Marshal von Manstein’s army group was in charge of a “pincer” maneuver.

Hitler had faith in Manstein because of his ability to turn around hopeless situations, and he did so by arranging impressive formations on paper. Hermann Hoth’s Fourth Armored Army, on the left, consists of 10 divisions, 200,000 men, and around 1100 armored vehicles (including the elite of the armored and mechanized formations, such as the SS Armored Corps of Hausser). This is a detachment of the Kempf army, on the right, with three mechanized brigades. General Model’s 9th Army was in charge of the northern end of the pincer. Model, an expert in defense who was popular with his troops but particularly harsh, fielded 21 divisions, 335 thousand men, and nearly 900 armored vehicles.

It became immediately clear that Manstein’s units would be responsible for the bulk of the offensive effort due to the temperament of the two concerned leaders and the disparity of their forces (and the air support that could be offered by a Luftwaffe already reduced by the lack of fuel). The victor of Sevastopol, in contrast to Model, was confident that his tanks could breach the Soviet defensive system’s fortifications and depth. An overconfident outlook brought on by weak German intelligence.

The Citadel of Stalin

The German military intelligence consistently underestimates the strength of the Red Army throughout the German-Soviet war. However, the partisans and an advanced eavesdropping system meant that the Soviets, despite their reputation as disinformation experts, were in the dark about German intentions. That allowed them to construct a strong defense. Beginning in March of 1943, more than 300,000 troops and civilians in the Kursk region set up eight defense lines, each one 300 kilometers in depth.

The German attack formations were supposed to be channeled by the trenches, minefields, and fortified points, and then destroyed by the armored reserves. The entire operation was kept secret using tried and true maskirovka methods, which was why the Germans had no idea of the full extent of the resistance mounted against them. Without a doubt, Model would have hesitated to launch the attack with his 9th army if he had known that he would have to face 80,000 mines, 2800 artillery pieces, and 537 multiple rocket launchers.

Stalin, who had recently granted Soviet generals greater autonomy, had obviously devoted a large amount of resources to protecting the Kursk salient. So that he can develop his own offensives (primarily Operation Kutusov towards Orel) in peace, the master of the USSR plans to make this salient a fixation point for the best German units. Central Front was led by General Rokossovski (Polish-born and a victim of the purges of 1937), who was stationed in the north to face Model. In order to complete his mission, the brilliant officer had access to multiple armies, or a total of 700,000 men and 1,800 armored vehicles (Soviet armies and divisions were smaller than their German counterparts). Rokossoskvi had time on his side and the option to use the reserves Stalin prudently amassed on his back if Model needs to break through in two days.

Young general Vatutin’s (42 years old) Voronezh Front is aligned with Manstein. Vatutin, a local who was familiar with his opponent, had a total of six armies at his disposal (two of which would not be attacked and would serve as reserves). There were a total of 1700 tanks and 625,000 men represented here. Not enough to stop Manstein’s offensive, but sufficient to set up a devastating counterattack. In fact, Vatutin, like Rokossovski, was aware that, in the long run, he can count on the assistance of two reserve groups he had amassed (including the Steppe Front) in order to counter the salient. The STAVKA (Soviet High Command) will send their two best officers, the brutal Zhukov and the level-headed Vassilievsky, to Kursk to coordinate their actions. A dynamic duo whose skillsets perfectly complement one another, able to hold their own against their Germanic rivals.

Two weeks to change the course of the war

Operation Citadel’s official launch date was finally settled on July 4th, 1943, after several delays caused in part by Hitler’s desire to supply his armored formations with the latest equipment (Panthers tanks, among others). With four months of planning and practice under their belts, the Luftwaffe Stukas will fly into action at 4 o’clock. The objective was to set up for the on-the-ground charge of Hoth’s 4th armored army.

Vatutin was unfazed by the brutality of the mechanized attack and maintains his composure. Russian defenses were strong because they were positioned on higher ground. The Soviet Union’s counterbattery fire and minefields were both highly effective. When the Luftwaffe took to the skies, the red-star planes severely hampered their ability to fight. But Hoth’s woes were compounded by the fact that the 200 Panthers making up its front line have been plagued by persistent mechanical issues. While in 1941 it would have been several dozen kilometers, on the evening of July 6 it was only a few kilometers.

Model had an even more trying time of it than everyone else. The 9th Army commander wisely followed the Soviet playbook and went in with infantry, later exploiting the situation with tanks (while Hoth rushes with its armor in the lead … to the Germans). Nonetheless, the implementation of these units was hampered by the activity of an admirably informed Soviet artillery late on the night of the 4th/5th (by deserters, among others). The Red Army’s resistance was strong, and the minefields significantly slowed the German advance, just as they had in the south. The 9th Army, at a cost of nearly 10% of its potential, broke through a 20 km wide and 7 km deep corner on the evening of July 5. The 6th Rokossovski had already begun their counterattack, so it would be a waste of money and a poor use of their time. Even though the Soviets suffer heavy casualties due to the poorly coordinated attack, the 9th army only loses a day. Sufficient time for Rokossovski to reflect on his setback and rethink his approach.

The Germans’ final great eastern offensive, at Kursk

By July 6, the Germans learn some encouraging news from the south. The 2nd SS armored corps (Hausser) was given the opportunity to attack in a poorly guarded area and made its way through toward Prokhorovka. The other Hoth army corps joined the breakthrough on the 7th, and the entire 2nd Soviet defense line was broken. As a result of the crisis, Stalin sent a large number of reserve formations, including the 5th Tank Army of Romistrov’s Guard, and Vatutin’s general staff was forced to respond (from Voronezh). Stalin had reason to be optimistic about continuing the operations despite Vatutin’s concerns. Even though the Hoth armored army had great success, the Kempf army detachment almost stalled in the north.

The 9th Army’s formations were showing signs of wear and tear due to constant bombing by Soviet aircraft. The strongest sectors of Rokossovski’s system were surrendered on July 9 by a Model that was unable to maneuver and was stuck in a logic of frontal assault. Model, a defense expert, realized right away that he was at a loss. On July 12, his superior, Marshal Von Kluge (Army Group Center), worried about his northern flank, ordered him to begin withdrawing. Half of the Battle of Kursk had been won by the Soviets at that point.

Therefore, the onus fell upon von Manstein to turn the tide. To be sure, he was upbeat because he had no idea how significant the Soviet Union’s upcoming reserves were. Hoth, frustrated by the positioning of Soviet forces, spends September 9th through 12th making his way to Prokhorovka, where the Schutzstaffel (SS) Panzers appear to have cleared the road. Killing Vatutin’s armored reserve would clear the way to Kursk, which was why he plans to do it. Nonetheless, the onslaught of Romistrov’s Guards tanks caught him and Hausser’s SS by surprise.

On July 12, the finest Soviet and German armored weapons will face off along a front of 8 km on both sides of the local railroad. Most recent studies agree that Prokhorovka was not the “swan song of the Panzerwaffe,” despite the fact that the battle was made out to be much more difficult than it actually was by Soviet propaganda. Although the SS armor was victorious on the defensive to some extent, they were unable to take the Prokhorovka railway junction due to heavy casualties and a lack of reinforcements.

Hitler called Manstein and Kluge to his headquarters in Rastenburg, East Prussia on the 13th. Though he was troubled by Hausser’s demise, he was even more so by some other information. The Western Allies had landed in Sicily and taken Syracuse three days prior. The Italian defense had been so ineffective that the island may as well be abandoned for the time being.

Thus, Hitler was compelled to organize a reserve army to protect the southern flank of Fortress Europe. This force could only count on the political stability of Hausser’s SS. The planet of Hoth cannot make significant progress without its spearhead. As a result, on the 17th, work on the Citadel was permanently halted. The gamble didn’t pay off, and the Führer had lost the upper hand on the Eastern Front. As a result, the German armies had no choice but to withdraw.

A critical moment in World War II

A major setback for the Hitler Reich was the inability of the Germans to take Kursk and completely destroy the Central and Voronezh Fronts. Although the Eastern Front did not shrink, the Red Army’s operational situation improved thanks to the creation of a strategic reserve. Worse, the Soviets still went ahead with Operation Kutusov on July 12 after Operation Citadel cost them 250,000 men against 60,000 Germans.

The myth of German invincibility was put to rest at Kursk. In the summer of 1943, the Red Army begins its campaign with a renewed vigor and the assurance that comes from knowing it can hold its own in mechanized combat. It had run out of chances to win.

Bibliography:

- Healy, Mark (1992). Kursk 1943: Tide Turns in the East. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-85532-211-0.

- Jentz, Thomas (1995). Germany’s Panther Tank. Atglen: Schiffer Pub. ISBN 0-88740-812-5.

- Jacobsen, Hans Adolf; Rohwer, Jürgen (1965). Decisive battles of World War II; the German view. New York, NY: Putnam. OCLC 1171523193.

- Mulligan, Timothy P. (1987). “Spies, Ciphers and ‘Zitadelle’: Intelligence and the Battle of Kursk, 1943” (PDF). Journal of Contemporary History. 22 (2): 235–260. doi:10.1177/002200948702200203. S2CID 162709461.

- Moorhouse, Roger (2011). Berlin at war: Life and Death in Hitler’s capital, 1939–45. London: Vintage. ISBN 9780099551898.

- Taylor, A.J.P; Kulish, V.M. (1974). A History of World War Two. London: Octopus Books. ISBN 0-7064-0399-1.

- Searle, Alaric (2017). Armoured Warfare: A Military, Political and Global History. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-9813-6.