Battle of Leuctra: A Military Masterpiece

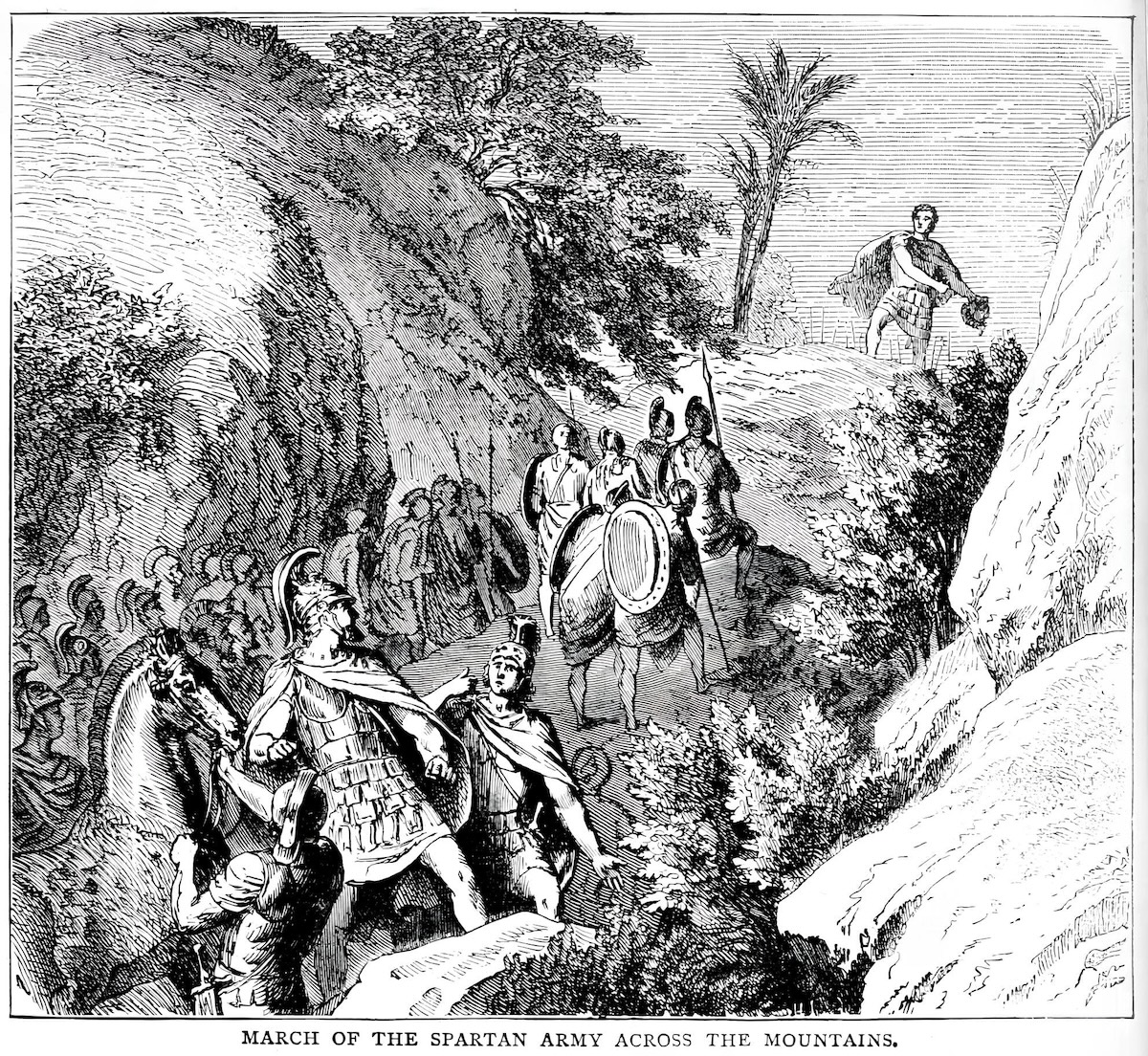

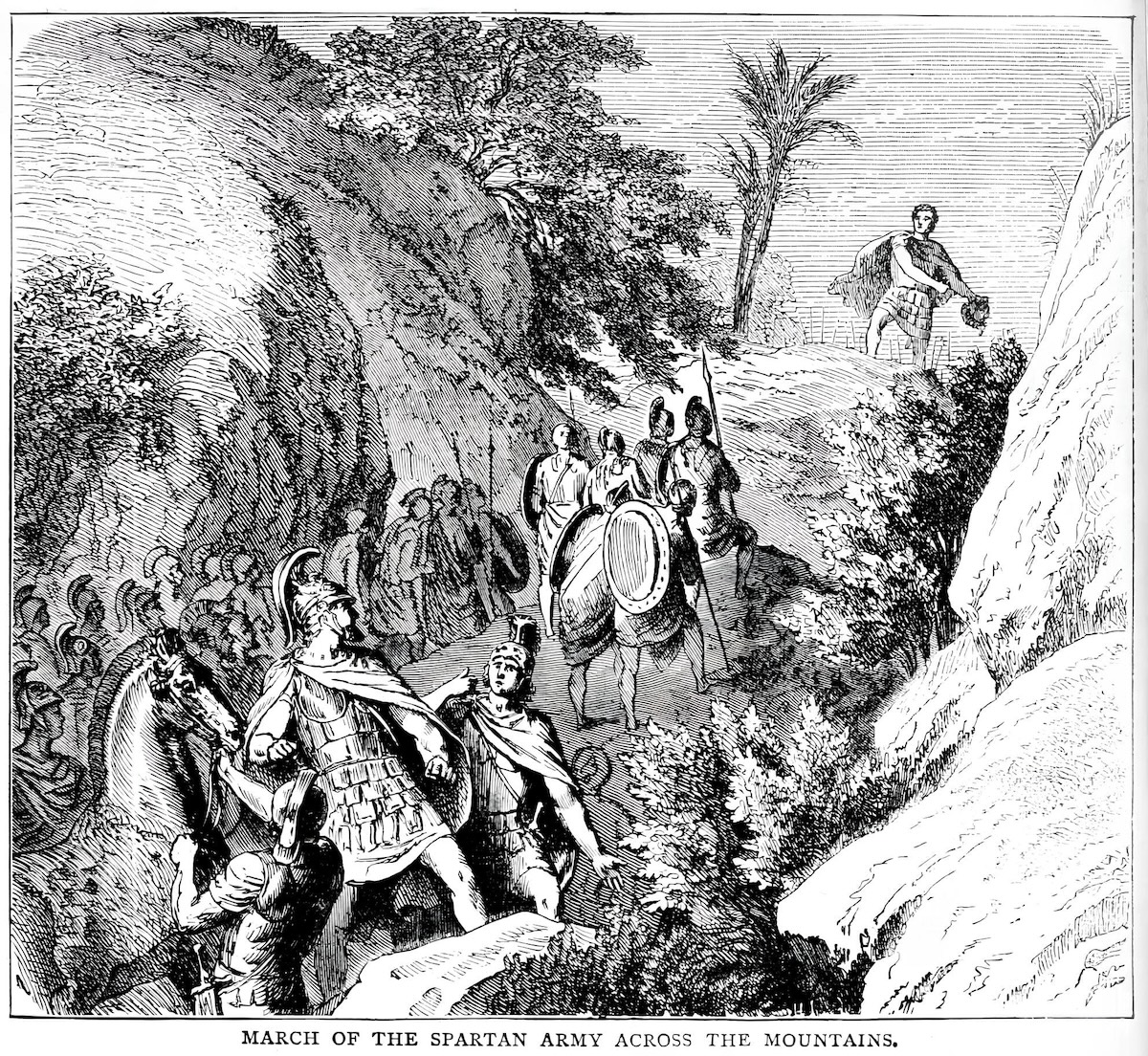

The Battle of Leuctra, which took place in 371 BC, is considered a turning point that radically changed the balance of power in Ancient Greece and ended Sparta's rule.

The Battle of Leuctra, which took place in 371 BC, is considered a turning point that radically changed the balance of power in Ancient Greece and ended Sparta's rule.