The Battle of Manzikert (1071) opposed the Byzantine army of Romanos IV to the Seljuk Turks commanded by Alp Arslan. The latter ultimately prevailed and took control of almost all of Asia Minor. The Eastern Conquest by the Turks was a major factor in the justifications for the First Crusade. After serving as slaves in the Abbasid armies for a while, the Turks rose to prominence in the political arena in the 10th century, with some earning the title of sultan from the caliph in order to establish independent principalities and spread Turkish power into neighboring regions like Syria and Anatolia. The Seljuks were one of these Turkish groups; they emerged as regional powerhouses and menaced Byzantium in the 11th century. The Battle of Manzikert marks the climax of the Seljuks’ and the Byzantines’ long fight against one another. But for what consequences?

The Seljuks were masters of the Muslim East

Until the eleventh century, the Turks were used as military slaves (the Mamluks) under Islam. The majority of the caliphal guard was composed of them beginning in the 9th century, and their ladies were common sights in the harems of Baghdad. The Turkic nomads eventually settled in the Muslim East, where they joined the Caliph’s army and adopted Islam. In the 11th century, the Abbasid caliphate was weakened, and the Buyid Shiites quickly took over, paving the way for the installation of the Turks. Certain of the latter rose to high ranks in the government as well as the armed forces, even earning the title of vizier in some cases.

In the 11th century, Seljuq of Oghuz (who gave their name to the dynasty) led a group of Turks to prominence. In the 1030s, they challenged the Eastern domination of the Ghaznavids and Buyids, and in 1055, their sultan Tughril (or Turul Bey) reached Baghdad and imposed himself as guardian of the Abbasid caliph al-Qa’im. De facto, they were in charge after pushing the Buyids out of the Abbasid capital.

But the Seljuk expansion continued beyond Iraq. Alp Arslan, who succeeded Turul Bey as sultan in 1063, beat back any opposition he faced and expanded even farther west, particularly into Anatolia. He also made threats against Syria and the territory held by the Fatimids of Cairo, an adversary of the Baghdad caliphate. The Seljuks were therefore in the thick of their conquering impetus on the eve of the Battle of Manzikert.

Reduced Byzantine power

Byzantium’s internal conflicts resurfaced in the 11th century. To be sure, when Basil II passed away in 1025, he did not leave behind any kind of dynastic successor. A struggle then ensued to find a new dynasty that could eventually replace the Macedonians. After Constantine VIII, the brother of Basil II, the ladies of this final generation “created” the emperors, and instability persisted for the next half century, despite Constantine IX Monomachos’ lengthy reign (1042–1055).

Faction rivals included the Macedonians, of course, but also Diogenes or, still based in Constantinople, the Komnenos. A member of this final dynasty, Isaac I Komnenos, gained temporary power in 1057 with the help of Constantinople’s Patriarch Michael I Cerularius (famous for his role in the schism with Rome in 1054). However, despite his talents, he wore out soon and had to make way for Constantine X Doukas only two short years later.

This new emperor will not have an easy time of it since the Byzantine Empire was constantly under assault from many fronts (Pechenegs, Normans, and eventually Turks). Around the year 1060, the latter increased their level of menace. In 1067, Constantine X passed away, and his wife Eudoxie became regent, with their son Michael VII Doukas succeeding him as emperor. However, Eudoxie immediately remarried to Romanos Diogenes, who was now the undisputed ruler of facts. Since his legitimacy was in question, Romanos IV Diogenes chose to conduct offensives against the foreign foes, especially the Turks Seldjoukides. The Battle of Manzikert will be precipitated by this.

Battle of Manzikert: A disaster foretold

Anatolia had been the target of Turkish incursions since at least the 1050s, when the first Turkoman invasions were conducted. Basil Apokapes and a force of Frankish mercenaries halted Turul Bey in front of the castle of Manzikert in 1054.

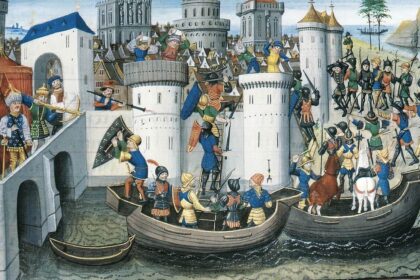

When Roman emperor Diogenes IV took over at Constantinople, the Seljuks were turned towards their great rival, the Fatimids. As of now, the Syrian city of Aleppo was the focus of Sultan Alp Arslan’s attention rather than Byzantine Anatolia. After taking Manzikert in early 1071, he struck a peace with the Byzantines and turned his attention to Syria. During this period, the Byzantine emperor finished preparing his army of roughly 70,000 soldiers for battle.

The basileus’s decision to split his army in two in March 1071, after crossing the Bosphorus, was his fatal flaw. Indeed, its best troops, led by strategist Joseph Tarchaneiotes, were sent to the north to reinforce the army of Norman mercenary Roussel de Bailleul. Some accounts state that they were defeated in a surprise attack by Alp Arslan, while others suggest that the strategist and the Normans were sabotaged by Doukas, partisans of the young Michael VII, who had been removed from power by his father-in-law and mother, Eudoxie. Regardless, and despite taking back Manzikert with relative ease, the basileus was weakened as a result of the Turks abandoning their siege of Aleppo in favor of the Byzantines.

Seljuk archers rapidly begin harassing Romanos IV Diogenes’s army, even throughout the night. But, oddly, the sultan seemed unsure of his might, at least for full-scale combat, and he sought to negotiate instead. As expected, this attempt was fruitless. This victory was crucial for the Emperor, not only to remove the threat posed by the Turks, but also to establish his authority and approach Constantinople with a victorious reputation. The forces arranged themselves in battle formation.

The basileus lined up his army of more than 50,000 troops on August 26, 1071, in a long, deep formation with numerous ranks, placing the cavalry on the sides. A number of generals, including the gifted Nikephoros Bryennios and, more surprisingly, the nephew of Constantine X, Andronikos Doukas Angelos, who showed no disguise for his disdain for the emperor, surrounded the monarch. They allowed the Greek army approach and shape into a crescent as the Seljuks’ army of 30,000 troops (most of them were mounted) made gallop their archers on the Byzantine sides, peppering them with arrows.

This hesitation to engage in frontal battle on the part of Alp Arslan rapidly led to the frustration of the Byzantine emperor, who was stationed in the middle of his army. The evening was drawing to a close, and he made the decision to go back—ironically, this was the time that the Sultan chose to begin his assault! The different accounts raise different questions, such as whether or not Andronikos Doukas, who would have been responsible for spreading the rumor of the basileus’s death, betrayed the basileus. While the Greek soldiers were retreating, were they ambushed by enemy forces?

The sultan’s onslaught on the Byzantine army had the same effect: he caused complete chaos, driving the last nail into the coffin. The nobility, led by Andronic Doukas, rapidly surrendered and retreated with the bulk of the mercenaries. Nikephoros Bryennios’ left wing was the only one to fight back and provide assistance for the center and Romanos IV Diogenes, preventing complete chaos and certainly many more casualties (which would have had even more dramatic consequences). The basileus was injured and had to return to the Turks after losing his horse.

The consequences of the defeat of Manzikert

When the Emperor was captured, the Empire suffered the ultimate shame. However, things were not as simple as that; the questionable validity of the basileus might rapidly resolve the issue. Despite this, the Sultan was providing decent care for his captive and was willing to take a reasonable price in exchange for his release.

That being the case, Romain IV Diogenes could return to Constantinople, but he won’t set foot inside while anticipating victory. On the contrary, he was welcomed by the supporters of Michael VII Doukas, decided to assert his right to the imperial throne and finally succeed his father. In situ but defeated, the emperor Romain IV Diogenes was imprisoned; one person destroyed his eyeballs while another put him up in a convent, where he soon died. But his wife, the future Emperor Michael VII Doukas’s mother, was exiled.

In spite of Romain IV Diogenes’ deposition and death, the Empire’s troubles were far from over. The political climate did not improve, the economic crisis worsened, and the Turkish advance in Armenia and Anatolia was cemented in the years that followed the Battle of Manzikert, despite the mild circumstances promised by Alp Arslan.

Even though the fall of Manzikert was a devastating blow to the Byzantines, the Turks moved on swiftly. The struggle against the Fatimids was still Alp Arslan’s primary priority. But soon after his triumph in Armenia, he was sent to the empire’s eastern provinces to quell revolts, and he was eventually killed in Transoxiana.

Malik Shah, his son, became much more powerful after him. During the years 1072–1087, he consolidated Seljuk control over Iraq and went on to take Mecca, Yemen, Damascus, Aleppo, and eventually Baghdad. However, the Seljuks let the Turkomans establish themselves in Anatolia.

But the end of Seljuk expansion occurred with Malik Shah’s death in 1092. A fresh fragmentation of the Near East occurred in the years leading up to Pope Urban II’s summons to the Crusade in 1095 due to succession disputes, the dominance of local emirs, the ever-present Fatimids, and the relative Byzantine rebirth under Alexios I Komnenos.

A pretext for the Crusade

The danger posed by the Turks, and in particular their military icon, Manzikert, is commonly cited as a reason for Pope Urban II’s decision to begin the First Crusade on November 27, 1095. Even in the West, the Turks had a poor image because of the Byzantines and the Fatimids. The West believed that this would have made it far more difficult for pilgrims to transit Anatolia on their way to Jerusalem. To make matters worse, they would have persecuted Christians throughout their possession of Jerusalem, much as the Fatimid caliph Al-Hakim did at the turn of the 11th century (he had burned the Church of the Holy Sepulchre).

Yet, it seemed that this line of reasoning was failing. The Seljuk conquest, on the other hand, stabilized the area for a while, and they seemed to have restored the rights of minorities, including Christians. There was little harm done to these groups by the internecine fighting among Turks or by the killings that followed Jerusalem’s insurrection against the Turkomans in 1076. But the memory of Manzikert endured, along with other remarkable stories like that of the Seljuk who were said to have shot arrows through the roof of the Holy Sepulchre.

As a result, the crusade was launched to save Byzantium and liberate the Holy Sepulchre from the infidels, of whom the Turks represented the most shared image. This was despite the fact that many Eastern Christians welcomed the Seljuk policy, including the author of The History of the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Severus ibn al-Muqaffa.

The date of the Battle of Manzikert was consequently important for several reasons: for Byzantium, for Eastern Islam and the Turks, and for the West, since it was sometimes cited as one of the many causes of the First Crusade, a topic of much discussion and dispute.

Bibliography:

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 563. ISBN 978-1-59884-336-1.

- Holt, Peter Malcolm; Lambton, Ann Katharine Swynford & Lewis, Bernard (1977). The Cambridge History of Islam. pp. 231–232.

- Nicolle, David (2013). Manzikerk 1071. The Breaking of Byzantium. p. 92. ISBN 978-1-78096-503-1.

- Barber, Malcolm. The Crusader States Yale University Press. 2012. ISBN 978-0-300-11312-9. p. 9