The Battle of Strasbourg in 357 pitted the Roman army, commanded by Emperor Julian the Apostate, against a coalition of Alamanni barbarian tribes attempting to invade Gaul. During the 4th century AD, the Roman Empire enjoyed a period of relative peace along its borders, particularly due to victorious military campaigns that restored the Roman army’s prestige. The Battle of Strasbourg, where Emperor Julian distinguished himself, temporarily halted major barbarian incursions across the Rhine, earning its victor immense prestige.

Context of the Battle of Strasbourg

In 357, the young Julian, appointed Caesar in Gaul by his cousin Constantius II two years earlier, fought against the Alamanni along the Rhine frontier to restore peace to the Empire’s lands. The Alamanni had occupied several towns and fortified positions in Roman territory because Constantius, in his struggle against the usurper Magnentius, had incited barbarian attacks behind enemy lines to weaken his rival. Even after winning the battle (Victory of Mursa in 351), the emperor did not resolve the border situation where the Alamanni remained firmly entrenched. Pressed by movements of the Persian Sassanids, Constantius tasked his cousin Julian with liberating the Rhine from the barbarian threat.

However, being extremely cautious with potential rivals, Constantius surrounded the new Caesar with a crowd of loyal men to keep this possible dissident in check. Despite this, Julian acted with boldness and clear-sightedness, and within a few years managed to improve the situation. Yet, the Alamanni threat was not completely crushed by Julian’s operations.

The army of General Barbatio suffered a crushing defeat, surprised and routed by the barbarians.

Julian the Apostate Facing a Surge of Violence

Upon hearing this, several Alamanni kings gathered their forces to reclaim the territory they had seized from the Empire. Among them were Chnodomar, Vestralp, Urius, Urcisin, Serapion, Suomar, and Hortarius. A particular incident further united the barbarians under a single banner: King Gondomad, a faithful Roman ally who kept his word according to Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, had been killed in an ambush, sparking a full rebellion against Rome.

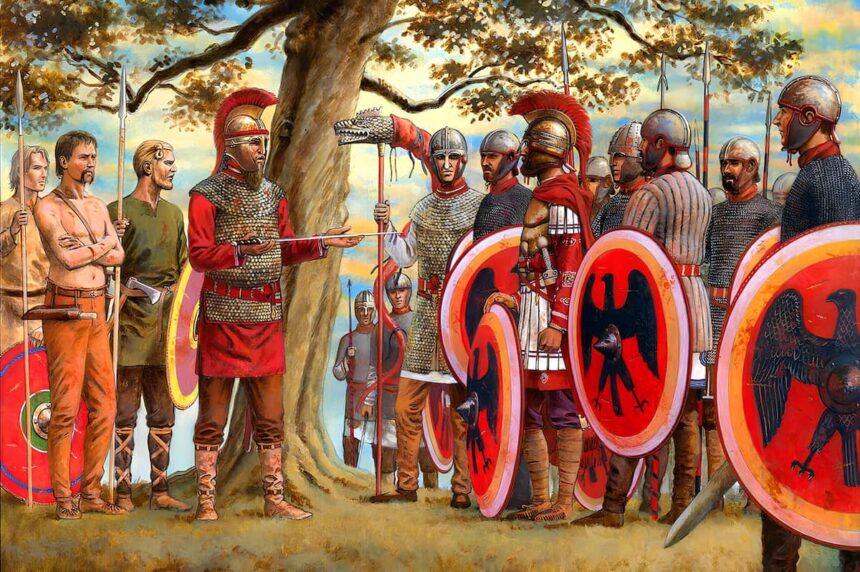

Informed by a deserter from the defeated army of Barbatio that Julian’s forces numbered only around thirteen thousand, the barbarians believed victory would be easy since their own army likely numbered around thirty thousand. Nevertheless, Julian resolved to engage in battle. Leading his army out of camp, he marched toward the barbarian fortifications. Upon reaching the enemy’s position, he gathered his troops and delivered a rousing speech. Energized by his words and proud to have an emperor among them, the soldiers made a tremendous noise, mixing shouts and the clashing of weapons against shields.

This behavior was typical of Roman fighters of the time, who, in a manner similar to the barbarians, expressed their warrior spirit through displays of raw violence. The almost miraculous leadership of a victorious emperor further heightened their combativeness. Given this, the senior officers of the army were also in favor of engagement, as dispersing the enemy into smaller pillaging units would create tactical and logistical nightmares, while also spreading terror among civilian populations.

Roman confidence was further bolstered by operations that Julian had previously conducted on barbarian lands beyond the Rhine, where they encountered no resistance, as the enemy had withdrawn without a fight. From the Romans’ perspective, they were about to face cowards who had refused to defend their own lands.

Setting Up the Armies

The Roman army established itself on a gently sloping hill, a short distance from the Rhine. An Alamannic scout fell into the hands of the soldiers and revealed that the barbarians had crossed the river over the course of three days and nights and were approaching their position. Soon after, the troops saw the barbarian warriors spread out across the plain and form a wedge—a narrow-front attack formation intended to break through the enemy lines in a swift charge. The Roman reaction was swift, and the soldiers formed what was described as an “impregnable wall” (Ammianus Marcellinus, XVI, 12, 20). Roman shields of the time were mostly circular, offering protection often compared to that of Greek shields.

Facing the Roman cavalry on the right flank, the barbarians positioned their own cavalry on the left, mixed with light troops, following an old Germanic tactic. On their right, taking advantage of a nearby forest, they advanced several thousand fighters to ambush the Romans. At the head of their forces, the kings were ready to lead by example.

Chnodomar, the driving force behind this coalition, was described by Ammianus as a formidable warrior with powerful muscles. Serapion commanded the right flank, a name derived from the fact that his father, held hostage in Gaul, had been initiated into the mysteries of Eastern religions.

On the Roman side, the left flank, commanded by Severus, halted on his order, as he sensed the barbarian ambush. Julian, with his 200 elite cavalry, moved through the ranks, encouraging his men while trying, as Ammianus noted, not to appear overly ambitious, as Constantius had placed him under close scrutiny. He organized his men efficiently, issuing loud exhortations to their pride as warriors.

Julian established his battle line in two rows, keeping the Primani legion and Palatine auxiliaries in reserve. These elite troops were heavily equipped, like the units in the front line. The legions of that time were smaller, likely around a thousand men, making them more mobile than the older legions of 5,000. For the “small wars” often waged by barbarians, these units were much more effective. Similarly, Palatine auxiliary units consisted of 500 men but usually operated in pairs, such as the Cornuti and the Bracchiati, positioned on the right of the front line.

These troops were largely recruited from the barbarian world, yet their combativeness and loyalty to the Roman Empire were noteworthy. They were highly reliable units, found in all theaters of operation. Sometimes their ardor was so great that they became difficult to control. It’s also important not to imagine Roman soldiers as always perfectly disciplined; the Romans allowed their men significant freedom for individual feats of arms, as long as it benefited the whole. Honorary rewards were provided for this purpose.

Battle of Strasbourg

As Julian fortified his position, shouts of indignation rose from the barbarian army. The troops feared that their leaders, mounted on horses, might take advantage of this and abandon them if they were defeated. The kings dismounted and stood with their men to boost their morale. The trumpets then signaled the start of combat. The violent clash of the armies took place in a cacophony of noise. The Roman line resisted stubbornly, its cohesion countering the barbarian frenzy. However, on the right, the Roman cavalry broke off from the fight against the barbarian cavalry and skirmishers.

Julian moved forward to stem the retreat, rallying the men who then returned to their positions. The Cornuti and Bracchiati also demonstrated their great valor, impressing the enemy with their courage and indomitable spirit. At the height of the battle, the Alamanni managed to break the Roman line in the center. But the second Roman line intervened; the Primani legion and the Batavians came in support, pushing back the threat.

Ammianus, describing the battle, portrays the Alamanni as equals to the Romans in warfare, perhaps to magnify Julian’s achievement but also likely out of respect for the barbarian combat prowess. It should be noted that a significant portion of the Roman army was composed of barbarians, though it’s incorrect to claim the army was almost entirely barbarized.

The Defeat of the Barbarians

The battle, though violent, continued in a near stalemate where more barbarians were dying. Better protected and more professional, the Romans effectively contained their enemies’ assaults to the point where the barbarians eventually broke and fled, pursued by Roman light units. The carnage was great, and many barbarians, terrified, fled by swimming across the Rhine, where many drowned. At the same time, Chnodomar, fleeing the disaster with a few warriors, hid on a wooded hill but was discovered by a Roman cohort. Surrounded, he surrendered.

The losses were very disproportionate, demonstrating the superior training and protection of the Romans. The Romans lost 243 men and 4 officers, while the Alamanni lost 6,000 on the battlefield, with an unknown number drowning in the Rhine. Ammianus is considered reliable in his accounting, leaving no doubt about the scale of the losses.

These figures closely resemble those from another famous battle: Marathon, where the Athenians also counted the dead, as they intended to offer a sacrifice for every Persian who fell. In that battle, 192 Greeks fell compared to nearly 6,400 Persians.

Epilogue of the Battle of Strasbourg

After the battle, Chnodomar was sent as a hostage to Rome, where he remained until his death. Julian, not wasting his advantage, launched bloody offensives into barbarian territory, stabilizing the frontier. The Battle of Strasbourg is a key moment in showcasing Julian’s tactical brilliance and his ability to inspire his men. His exploits were remarkable, and he was never defeated in a pitched battle. His men would follow him even into the burning sands of Persia, refusing to join Constantius II.

Enveloped in the prestige of victory, Julian became a victorious emperor, favored by Fortune, destined to free himself from oppressive oversight, now that his men were entirely loyal to him.