The Battle of Svolder, fought around the year 1000 AD, stands as one of the most dramatic naval engagements of the Viking Age. This confrontation not only shaped the political landscape of Scandinavia but also marked the demise of one of Norway’s most legendary kings, Olaf Tryggvason. Rooted in both historical accounts and saga literature, the battle exemplifies the era’s complex interplay of power, religion, and alliance.

Historical Context

By the late 10th century, Scandinavia was a mosaic of rival kingdoms and jarldoms. Olaf Tryggvason, a charismatic leader and devout Christian, ascended the Norwegian throne in 995 AD. His reign was marked by aggressive efforts to Christianize Norway, often clashing with pagan chieftains and neighboring rulers. His ambitions unsettled Sweyn Forkbeard of Denmark and Olaf Skötkonung of Sweden, who viewed Olaf’s growing influence as a threat. Additionally, Norwegian earls like Erik Hakonarson, whose father had been ousted by Olaf, sought to reclaim power.

Who were the main leaders of the battle?

Catalysts for Conflict

Tensions escalated due to Olaf Tryggvason’s marital diplomacy. His union with Thyri, Sweyn’s sister, allegedly without consent, provoked Danish ire. Moreover, Olaf’s coercive Christianization alienated regional leaders. The final trigger was an alliance forged by Sweyn, Olaf Skötkonung, and Erik, who plotted to ambush Olaf during his return from Wendland (modern Poland).

The Battle: Saga Accounts and Reality

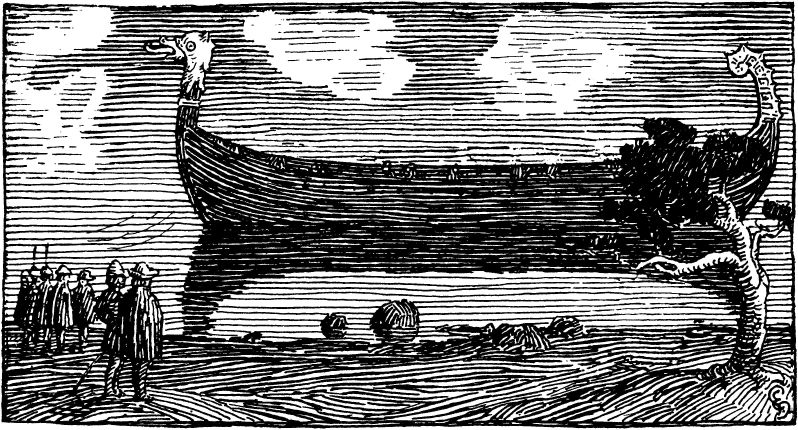

According to the Heimskringla and Jómsvíkinga Saga, Olaf’s fleet was lured into a trap near the island of Svolder—a location still debated, with theories suggesting the Baltic’s Rügen or Øresund. The sagas depict Earl Sigvaldi, a Jomsviking leader, deceiving Olaf into splitting his forces, leaving him vulnerable.

Olaf’s fleet, though smaller, was formidable. The Long Serpent. (Ormrinn langi), with its 34 benches, became the battle’s centerpiece. The allied forces, leveraging superior numbers, encircled Olaf’s ships. After a fierce clash, Olaf’s men were overwhelmed. The king’s fate remains enigmatic: he either perished in combat or leapt into the sea, evading capture.

Aftermath and Legacy

Olaf’s death led to Norway’s partition: Sweyn took the Trondelag region, Olaf Skötkonung acquired Ranrike, and Erik Hakonarson governed the west. This fragmentation underscored Norway’s vulnerability until its reunification under Olaf Haraldsson (St. Olaf) in 1015.

The battle also stalled Christianization efforts temporarily, though Sweyn and Erik later permitted missionary activity, blending pragmatism with faith.

Historiography and Sources

Primary accounts, notably Snorri Sturluson’s sagas, blend history with legend. Exaggerations in ship numbers (e.g., Olaf’s 11 ships versus hundreds of allies) and heroic motifs reflect oral traditions. While archaeological evidence is scant, the sagas offer cultural insights, portraying Olaf as a martyr-king and Svolder as a moral tale of hubris and betrayal.

The Battle of Svolder epitomizes the Viking Age’s turbulent politics and cultural shifts. It underscores the fragility of power and the enduring allure of legendary leadership. As both history and myth, Svolder remains a testament to an era where the sword and the cross shaped nations.

Number of ships according to various sources

| Source | Olaf Tryggvason | Olaf the Swede | Eirik | Svein | Allied total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oddr Snorrason | 11 | 60 | 19 | 60 | 139 |

| Ágrip | 11 | 30 | 22 | 30 | 82 |

| Historia Norwegie | 11 | 30 | 11 | 30 | 71 |

| Theodoricus monachus | 11 | – | – | – | 70 |

| Rekstefja | 11 | 15 | 5 | 60 | 80 |

Source Criticism and Historiographical Challenges

- Skaldic Poetry: Contemporary skaldic verses (e.g., Hallfreðar saga) provide fragmentary evidence but are often laudatory or allegorical.

- Sagas: Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (13th century) and the Jómsvíkinga Saga (12th–13th century) are key but problematic. These texts blend oral tradition with political agendas, portraying Olaf Tryggvason as a Christian martyr and his enemies as pagan antagonists.

- Continental Chronicles: Adam of Bremen’s Gesta Hammaburgensis (1070s) and Thietmar of Merseburg’s Chronicon (1010s) offer external perspectives but are biased toward Christianization narratives.

Key Debates:

- Chronology: The exact date (999–1003) and location (Rügen? Øresund?) remain contested. Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus placed it near Zealand, while Icelandic sagas emphasize Wendish waters.

- Numbers: Saga claims of hundreds of allied ships are likely exaggerated. Archaeologist Jan Bill argues that even 70 ships would represent an unprecedented naval force for the era.

- Olaf’s Survival: Some folktales (e.g., Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar en mesta) claim he fled to Byzantium or a hermitage, reflecting his mythic status.

The Battle’s Role in State Formation

- Norway’s Fragmentation: The tripartite division (Denmark, Sweden, Earl Erik) underscores the fluidity of medieval Scandinavian borders. Erik Hakonarson’s rule (as a Danish vassal) highlights the era’s “overlordship” model, where power relied on alliances rather than centralized authority.

- Sweyn Forkbeard’s Ambitions: Svolder solidified Danish dominance in the Baltic, paving the way for Sweyn’s invasion of England (1013) and his son Cnut’s North Sea Empire.

- Christianization vs. Paganism: Though Olaf’s death stalled Norway’s Christianization, his martyrdom became a rallying point for later kings like Olaf Haraldsson (St. Olaf), who completed the process by 1024.

Naval Warfare and Viking Ship Technology

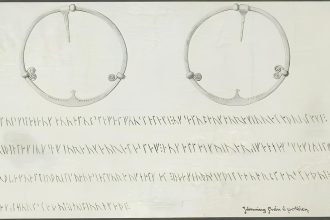

- Ship Design: The Long Serpent (reported as 34–50 meters long) was a dreki (dragon ship), optimized for speed and intimidation. Smaller karvi and snekkja vessels were used for flanking.

- Battle Tactics: Sagas describe “ship-binding” (skipfesting), where crews lashed vessels together to form floating platforms. This tactic, while stabilizing, limited maneuverability—a vulnerability exploited by Erik Hakonarson’s forces.

- Archaeological Parallels: The Gokstad and Oseberg ships (9th century) provide context for shipbuilding techniques, though no wrecks from Svolder have been identified.

Religious and Cultural Dimensions

- Olaf’s Christianizing Legacy: Despite his forced conversions, Olaf’s alliance with English missionaries (e.g., Bishop Sigurd) laid groundwork for Norway’s ecclesiastical infrastructure. Post-Svolder, Sweyn and Erik allowed incremental Christianization to avoid revolts.

- Pagan Resistance: The alliance against Olaf included pagan holdouts like Sigvaldi Strut-Haraldsson of the Jomsvikings, whose semi-legendary warrior brotherhood symbolized pagan martial ideals.

Modern Interpretations and Nationalism

- 19th-Century Romanticism: Norwegian nationalists (e.g., Henrik Wergeland) mythologized Olaf as a proto-nationalist hero, while Danish scholars framed Svolder as a triumph of “pan-Scandinavian” cooperation.

- Nazi Era Misuse: The Jomsvikings were erroneously glorified by the SS as Aryan warrior prototypes, distorting historical understanding.

Recommended Reading: