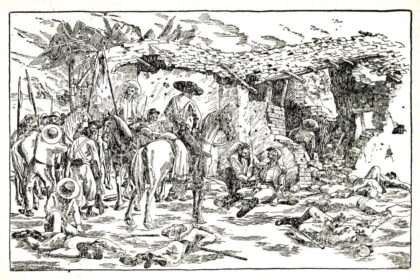

Battle of the River Plate: Hunt for the Graf Spee

The Battle of the River Plate was a naval engagement that took place during World War II near the estuary of the River Plate in South America. It involved the German pocket battleship Admiral Graf Spee and the British cruisers Exeter, Ajax, and Achilles.