Belphegor, also written as Belfegor and Balphegor, (Hebrew: בַּעַל-פְּעוֹר baʿal-pəʿōr – Lord, or Baal, of Pe’or, or of the opening) is the name of a demon in Jewish and Christian tradition. Originally, it was the name used in the Septuagint (Βεελφεγώρ) and later in the Vulgate (Beelphegor) for the Moabite god Baal Pe’or. Later, it was assigned to a demon. As such, Belphegor is part of the Christian religion and became a character in Renaissance literature and modern popular culture.

Origin and History

Baal Pe’or

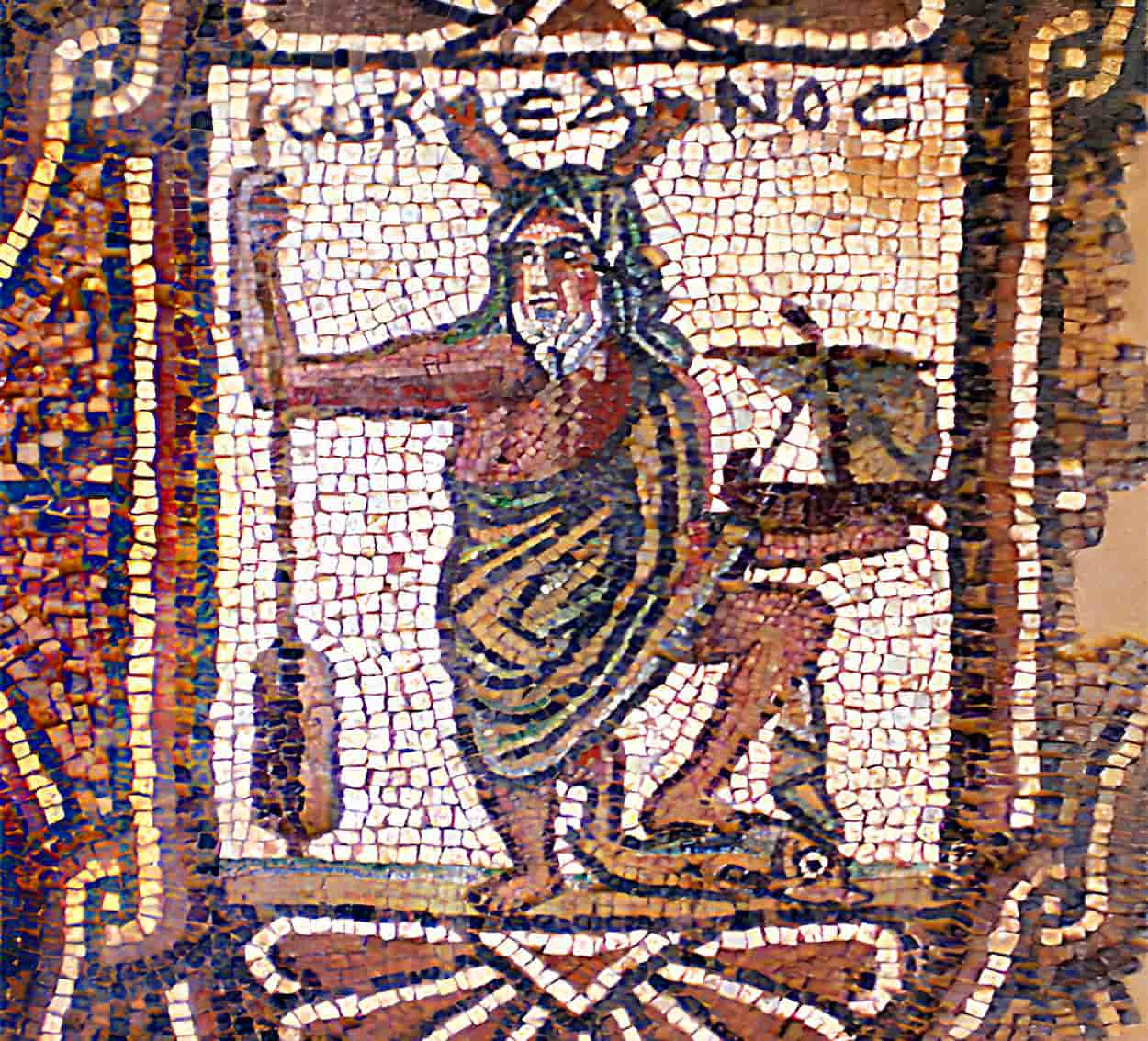

Like many demon names, Belphegor originates from the Canaanite god Baal, according to the accounts in the Bible. Indeed, Baal Pe’or is the name of a Moabite deity that appears in the Book of Numbers (25:1-15) and in Deuteronomy (3:29), whose cult tempted the Israelites before entering the Promised Land. Baal can be understood as a title, meaning “lord” in that sense, or as the name of a specific god. In the case of Baal Pe’or, it is unknown whether it is a Moabite deity, an epithet of some other god, such as Kemosh, or of the god Baal himself venerated on Mount Pe’or. Nothing is known about its cult either, and modern descriptions are based exclusively on the biblical version and the deductions of later scholars.

According to the biblical account, while the Israelites were camped in Sittim, the plain of Moab, they began to associate with the women of the region; these women then led them to worship the god of Mount Pe’or. This temptation, according to later texts, was due to a suggestion from the prophet Balaam, summoned by the Moabite king Balak to curse Israel from the top of the mentioned mountain, but who ended up blessing it. Upon descending from the mountain, Balaam told the king that the only way to defeat Israel was by corrupting it through lust, which would lead them to worship other gods.

The king accepted, and the Moabite (or Midianite in another version) women seduced the Israelite men, leading them to the cult of Baal Pe’or. Such idolatry caused a plague, Yahweh’s punishment, which claimed the lives of over twenty thousand Hebrew people. The episode ends when Moses orders the idolaters to be executed, and the priest Phinehas, grandson of Aaron, kills a leader of the tribe of Simeon who was having relations with a foreign Midianite woman. This account, created to discourage marriage with foreign women, was incorporated into the Bible, along with the name of the pagan god Baalpeor or Belfegor.

The Demon Belphegor

In Judaism of the 1st century BCE, and from it, in later Christianity, the names or epithets of the Canaanite gods were assigned to demonic entities that formed a kind of realm of evil opposed to that of God. In the texts of the Qumran, in amulets, and in Jewish and Christian apocryphal writings, numerous angels and demons are mentioned whose names derive from the Canaanite gods. In this case, the legend contained in the Book of Numbers and the belief that pagan gods were demons combined to turn this Moabite deity, whose cult still existed according to the Tannaim, into the demon Belphegor.

Later authors developed the character by giving it certain specific characteristics. The toponym Pe‘or was related to the Hebrew root פער p‘r which indicates opening, both of the mouth and of the intestines. Baal Pe’or, then, was interpreted as ‘Lord of the Opening’. This sense is probably the source of Talmudic traditions associating Ba‘al Pe‘or with nudity and excrement. In the Talmud, the tractate ‘Avodah Zarah (3) states that Pe’or was used as a latrine and that the worship of Baal Pe’or consisted of defecating before the idol. In the same vein, the commentator Rashi notes that Pe’or was called so because they exposed their anus to him and produced excrement. From the same root, the worship of this god was associated with the deflowering of maidens, especially because the passages alluded to could be interpreted as “breaking of fornication” (although in the context fornicating is equivalent to idolatry) and therefore Baal Pe’or was identified with Priapus.

Christian exegetes wrote numerous works about demons; for theologians like Saint Augustine or Saint Thomas Aquinas, they were agents of evil against whom the faithful should take moral and cultural precautions (virtuous conduct and invocations to God). Other authors, however, developed demonology with detailed descriptions of infernal beings from Jewish literature and classical legends, as well as from popular beliefs or folklore.

These writings are very detailed, explaining the names, appearances, and traits of numerous demons, and although they were never fully endorsed by Christian churches, they enjoyed great acceptance among Catholics as well as among Orthodox and Protestant believers. At the same time, a whole literature of magic and esotericism developed, such as grimoires and treatises on magic, which taught how to summon evil spirits. Since it was necessary (according to the theory of magic) to know their names, such works contain lists of devils with their corresponding invocation. Finally, books aimed at persecuting heresy and witchcraft also often contain a kind of “who’s who” in Hell. Belphegor prominently appears in all of them.

However, it is later works such as Collin de Plancy’s Infernal Dictionary that systematize demonology, and from them, characters like Belphegor are taken up by literature and music. At the same time, and under the influence of the biblical narrative, the first scholars of Semitic mythologies attributed to the Moabite god Baal Pe’or, of which little is known, some of the characteristics of the demon in later tradition.

Appearance and Characteristics

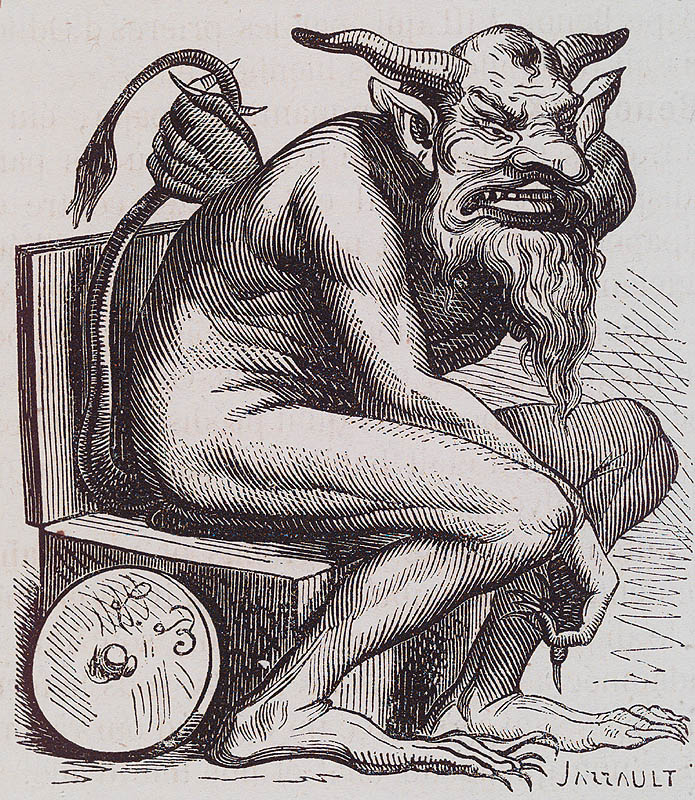

Belphegor appears in illustrations as a robust demon with the face of an old man, a large nose, a long beard, horns, and claws. He is always depicted sitting on a kind of throne that is actually a latrine.

Peter Binsfeld, a German bishop of the 16th century, assigned a principal demon to each of the seven deadly sins. Sloth, or more specifically, Acedia, was considered the responsibility of Belphegor. In Johann Weyer’s contemporary work De praestigiis daemonum, Belphegor is mentioned as a symbol of the caves where offerings were thrown during a sacrifice.

Based on these and other sources, Collin de Plancy writes in his aforementioned Infernal Dictionary:

“…demon of ingenious discoveries and inventions. He often takes the form of a young woman. He provides wealth. The Moabites, who called him Baalfegor, worshipped him on Mount Fegor. Some rabbis say he was honored in the latrine and offered the residue of digestion, of which he was deserving. It is for this reason that certain scholars see in Belphégor the god Crepilus and others argue that he is Priapus. – Selden, cited by Banier, asserts that human victims were offered to him, whose flesh was devoured by his priests. Wierus comments that he is a demon who always has his mouth open; an observation that undoubtedly comes from Pégor, which means, according to Leloyer, crack or fissure, because he was sometimes worshipped in caves and offerings were thrown into his openings.”

Infernal Dictionary, ed. 1863, s. v. Belphegor

Character during the Renaissance

Belphegor appears as the protagonist of a tale (favola) by Machiavelli; Belfagor arcidiavolo (“Belphegor, the archdevil”) written between 1518 and 1527 but published in 1549. In this tale, the demon Belfagor, under the name Rodrigo de Castilla, is sent to Earth by Pluto to ascertain if married life is worse than Hell. The character serves, then, as a way to criticize the society of his time through satire.

Machiavelli’s work, which also appeared in an abbreviated form under the name Giovanni Brevio in 1545, and in Giovanni Francesco Straparola’s Le piacevoli notti, was imitated throughout Europe: by Hans Sachs in Der Dewffel nam ain alt Weib zw der Ee, die in vertrieb (1557) and by John Wilson in the drama: Belphegor, or The Marriage of the Devil (1691).

In Milton’s poem, Paradise Lost, Belphegor is identical to Nisroc (Hebrew form of an Assyrian god) and, before his fall, “the first of the Princes.” He then becomes one of Satan’s closest confidants.

In modern literature

- French writer Arthur Bernède published in 1927, Belphégor, le fantôme du Louvre, a popular horror novel. In it, Belphegor, as the title indicates, is a ghost who, like Gaston Leroux’s Phantom of the Opera, inhabits the Louvre museum. Based on this novel, four films were made.

- He is a character in the short story “Birthday Party” by Ariel Cambronero Zumbraro.

- The title of the second book in Antonio Malpica’s saga The Book of Heroes is Nocturno Belphegor.

In film and television

- Belphégor (1927) Four-part series of 55 minutes each. Directed by Henri Desfontaines with Jeanne Berangere, Jeanne Brideau, Alice Tissot, Elmire Vautier, and Michele Verly. The series was produced by Pathé and restored in 1994 by the French Film Institute. In 1996, this version was released in Italy under the Yamato Video label.

- Belphégor or the Secret of the Louvre is also the name of a successful French suspense television series from 1965, directed by Claude Barma and starring Yves Rénier, René Dary, Juliette Gréco, Christine Delaroche, and Sylvie.

- Belphégor, a 26-part animated series from 2001, produced by the French broadcaster France 2.

- Belphégor, le fantôme du Louvre (Belfagor – The Phantom of the Louvre) a 2001 film, also known as The Mask of the Pharaoh, directed by Jean-Paul Salomé starring Sophie Marceau, Michel Serrault, and Julie Christie.

- Supernatural, Season 15 (2020). He is a minor demon, in charge of the administrative area of the souls that arrive in hell. Portrayed by actor Alexander Calvert, the demon takes over the body of Jack Kline, a nephilim who had just been murdered. He appears in the early episodes helping the protagonists fight the souls that have escaped and return them to hell.

Belphegor’s number

Belphegor’s prime number is a numerical sequence that contains the number 666.